By Joel Drucker

The assignment called for a review of All In, the legendary Billie Jean King’s autobiography (written with Johnette Howard and Maryanne Vollers). But given the quality of the times I’d spent with her, I knew that maintaining journalistic distance from this epic work was impossible. Of course, hundreds of people—probably thousands—had interacted with King personally in ways different from the public persona of net rusher, crusader, icon. Over the past 30 years, I’ve spoken with many, not just King’s fellow world-class players, but volunteers from USTA sections, fans, recreational players, racquet stringers, drivers, ball persons, airline passengers, camera operators, TV producers, makeup artists, even a colleague who’d once briefly rented her Hawaii home.

My contact with her too had been distinct. There’d been early mornings and late evenings in London, when we worked for HBO during Wimbledon. There’d been long conversations about two iconic facilities, the Berkeley Tennis Club in Northern California and the Los Angeles Tennis Club in Southern California, where we’d each played frequently and come to understand much about the game’s culture and history. There’d been dialogue about competition, King offering this enthralling human insight about the sport’s champions: The better players? Oh, we just choke 10 percent less.

But most of all, I’d been touched by King’s desire to learn about my late wife, Joan Edwards. The time Billie Jean came to Berkeley and I’d conducted a public interview with her when the club hosted the National Girls 18s tournament, she insisted on dining with Joan. King during that meal had kindly peppered her with questions and comments about her ongoing struggles with lupus, an autoimmune disease. Afterward, Joan said how glad she was that someone was willing to actually face rather than evade the topic of her health. She added that the pace of conversation with King was thrilling and made her feel as if she had just participated in some sort of verbal volley drill.

In 2010, during what proved the last summer of Joan’s life, King had sent her several thoughtful notes. As fate had it, she died in the same Berkeley hospital where King had once tended to a significant medical matter of her own. That affinity provided at least a degree of succor for my shattered heart. In the following months and well beyond, King reached out to me frequently. Based on all this, there was no way I could clinically dissect All In. Then again, I wouldn’t be the first person to review a book authored by a friend.

As All In comprehensively demonstrates, Billie Jean King is all about tennis and not about tennis and all about tennis. The first third of her life—the quarter century leading up to the creation of Open tennis in 1968—had largely been a private matter, tennis during that time scarcely popular. In 1967, King won Wimbledon and the U.S. Championships and estimated her earnings that year to be no more than $20,000.

But thanks in large part to the efforts of King, eight of her peers, and one moxie-fueled magazine publisher, tennis soared in the early ’70s. King occupied the tennis boom’s red-hot center, deeply involved in everything from the creation and promotion of the Virginia Slims Circuit to the passage of Title IX, the infamous “Battle of the Sexes” match versus Bobby Riggs, the creation of such enduring entities as the Women’s Sports Foundation, World Team Tennis, and the Women’s Tennis Association, and a host of other interactions with the world of politics and culture. A significant breakthrough happened in 1971, when King became the first female athlete to earn $100,000 in a calendar year. King’s achievement generated a call from her fellow Californian, Richard Nixon. “The president of the United States was recognizing me the same way he would a returning astronaut or a Super Bowl-winning quarterback,” writes King, noting that only five major league baseball players made more that year. Revolutionary and inclusive as she was, King was also keenly aware of this cultural reality: Money talks.

Politicians, activists, athletes, executives, entertainers; this was the galaxy of fame and fortune King came to occupy. For nearly 50 years, the planet seemed to possess her. No wonder that on those occasions I’d socialized with her, she’d frequently declared herself an introvert, zealous in her pursuit of private time. I always laughed that off and told her there was no question she was an extrovert. True to form, she asked why. That was the start of a typical King query sequence. Why? How come? What do you think? Is that really true? I need to learn more about that. I never thought about it that way. Tell me what I should read. King’s high level of interest in the thoughts and backgrounds of others was extremely rare for anyone, much less an athlete, much less an athlete in an individual sport, much less a champion, much less one who’d been lionized by presidents.

But then again, as King loves to point out, it was the spirit of inquiry that made her a champion, as she explains when exploring the decision to drop out of college. “It’s a paradox,” King writes. “I know. I value education. I’ve always had a huge appetite for learning that persists to this day. I’ve always loved drilling down to the details, meaning, and origin of things. In hindsight, I guess the best way I can explain that time is that I was one of those restless students who wasn’t on a quest for a framed degree I could hang on the wall as much as for insights and information that dovetailed with what I hoped to do with my life, which was tennis. Tennis always seemed to dominate.”

So perhaps, even beyond fantastic volleys and off-the-charts match management skills, King’s greatest asset was her curiosity. Spend 30 minutes with King and you might touch on anything—psychology and history, her eternal quest for a better forehand, movement patterns, followed by a sudden jump to an interaction she’d had with Michelle and Barack Obama, Hillary Clinton, Gloria Steinem. And then she’d redirect the conversation and ask about the personality and technical approach of an iconic teaching pro and see how it connected to coaches she’d worked with. Having majored in history—and at a college King was quite familiar with—I particularly liked how she treated that subject like a living, breathing organism, open to constant exploration of society and self. As she’d said often, “How can you shape the future if you don’t study the past?”

King, of course, hadn’t just studied history. She’d made it: inquiry channeled into action, a mind on fire to examine and reinvent everything from her service motion to social justice. At the Berkeley event, I’d asked her how long it took to recover from those heady days and long nights of the early ’70s. She made a joke that really wasn’t: “I’m still recovering.”

The juxtaposition of life as public figure and private person makes All In extremely compelling. As a Californian myself, I particularly liked that King was one too and how that state’s pioneer spirit had shaped her journey. During King’s formative years, Southern California was unquestionably the richest and deepest tennis spot in the world. King devoured all it had to offer. “When I look back now,” she writes, “I’m amazed at the personal contact I had with so many accomplished players and people who helped me. Those experiences helped make me the human being and player I became.”

But that doesn’t mean it was easy. Southern California tennis czar Perry Jones excluded the 10-year-old Billie Jean from a group photo taken at the Los Angeles Tennis Club because she wasn’t wearing a proper skirt, an action that triggered her social consciousness and desire to question the tennis establishment. Former world No. 1 Alice Marble mentored the teenage King for more than a year until a misunderstanding compelled an angry Marble to end their partnership. Another great champion, Maureen Connolly, told the young Billie Jean that she lacked the goods to become a champion—but years later confessed to King that she had actually believed highly in her, only deploying harsh comments as a motivational tool. And then there was Jack Kramer, the big-time player, pro tour promoter, and L.A. tournament director who in 1970 offered the women so little in prize money that King and eight of her fellow players ditched that event and joined forces with Gladys Heldman to start the Virginia Slims Circuit. True to her California-bred sensibility of grand ambition, King writes, “I still wanted to believe that I could lead a life without limits. But as I got older and looked around, it increasingly seemed like the world was telling me something else.”

By the time the Virginia Slims Circuit began in that tumultuous fall of 1970, King had been living in Northern California for four years. In 1966, just over a month after she won the first of six Wimbledon singles titles, King moved with her husband Larry to Berkeley, as he had just commenced law school there. It was a time and place of great tumult that in many ways further crystallized King’s desire to change the world. “In Berkeley,” she writes, “it seemed like everything in American life was being reexamined, including what it meant to be a woman and women’s roles in the workplace and society. I was questioning where I fit in too.”

For a time in the ’70s, there were rumblings that King might fit in somewhere beyond tennis. That didn’t quite happen. Back in those days, champions of women’s liberation, often focused on such overtly political actions as the passage of the Equal Rights Amendment, failed to fully grasp the cultural and social impact an athlete could make. Then, in 1981, there came King’s nasty public outing, the result of a lawsuit filed by former lover and onetime assistant Marilyn Barnett. As King writes, “Marilyn’s betrayal was such an utter breach of privacy and trust, such a soul-destroying violation and trauma for me, I would never wish being outed on anybody. Nor would I ever out anybody else. I sometimes ask myself, Would I ever have been ready to come out on my own? I think so. But it should have been my choice. Nobody should have to come out unless they’re ready.”

The lawsuit with Barnett, along with the end of her playing career and the eventual breakup of her marriage to Larry, were just a few of the occurrences that helped King further explore a number of psychological issues, ranging from family to eating and more. She delves into these with wisdom and sensitivity. There are also many thoughtful passages about her longstanding romance with former pro Ilana Kloss.

A spirit of high-mindedness pervades All In. At this stage of her life, King the lifelong crusader has made plenty of room for evenhandedness. Assessing her biggest rival, the controversial Margaret Court, King writes, “Our politics would grow increasingly far apart later in life when she repeatedly attacked the LGBTQ+ community—even kids—and I called her on it. But in 1964 she was, like all the Aussies I met, unfailingly gracious and hospitable…. We actually had some things in common, from our blue-collar roots to our deep religious faith to our love of our sport.”

It’s also gratifying to see how King was rediscovered by a new generation of women athletes in other sports, for whom her windmill-tilting mindset was an inspiration. Having spent my whole life studying her from inside the tennis court—starting with a vivid image of seeing her hit volleys the summer I turned 12 and first played a tournament—it’s remarkable to hear athletes who wouldn’t know Lendl from lentils describe what she’s meant to them. Of all sports, it was tennis and its quirky mix of elitism and populism that lit the fuel for the likes of basketball and soccer.

But as All In reveals in detail, King’s journey was arguably as epic as any in the history of sports. She’d made herself a champion, evolved into an activist, survived ostracization, continued to crusade. Through it all, she remained as resolutely and relentlessly upbeat as that child who, within minutes of holding a tennis racquet for the first time, determined her life’s purpose.

Damn it, I thought, as I wrote that prior sentence. What had I added to the dialogue with those words? The world already knew all this about Billie Jean King. All In will make sure it never forgets.

But I wanted to convey another dimension; less the obvious verbiage of banquets, instead something idiosyncratic and therefore arguably more vivid. Those were the moments when I’d gained a highly personal and intimate glance into this champion’s soul. “Check this out,” King told me as a man approached her on the deck of the Berkeley Tennis Club. “He’s going to tell me how what I did helped women’s tennis. Doesn’t he understand we helped all of tennis?” In the same way that King had won 39 Grand Slam titles anticipating passing shots, the pattern played out perfectly. Once the man left, we resumed our ongoing discussion about why Californians for many decades often had better backhands than forehands. We then shared a laugh about a legendary player who’d told the young Billie Jean that her forehand grip simply would not “hold up” (his words) under pressure.

A decade later, near midnight in the players’ lounge of the Australian Open, the topic was talent. I asked her to define it. Was it simply a matter of who was more smooth, graceful, powerful? She reflected on her path and soon agreed that there was more to talent than raw physical elegance. Then Billie Jean issued another statement made highly credible by her staggering résumé: “Persistence is a talent.”

I particularly took that premise to heart, literally so because King had described Don’t Bet on It, the book I’d written about my marriage and Joan’s death, as “a beautiful and passionate tale of two first-rate competitors who fought hard for their love.” It felt gratifying for King to recognize the connection between love and tenacity. Like the rest of the world, I’d taken in her story for decades. But for a few moments, she’d taken in mine. I knew I wasn’t the only one she’d done that with. The world was filled with people who wanted to be interesting. It was another thing to be interested. All In is an engaging tale of someone who has spent a lifetime being both.

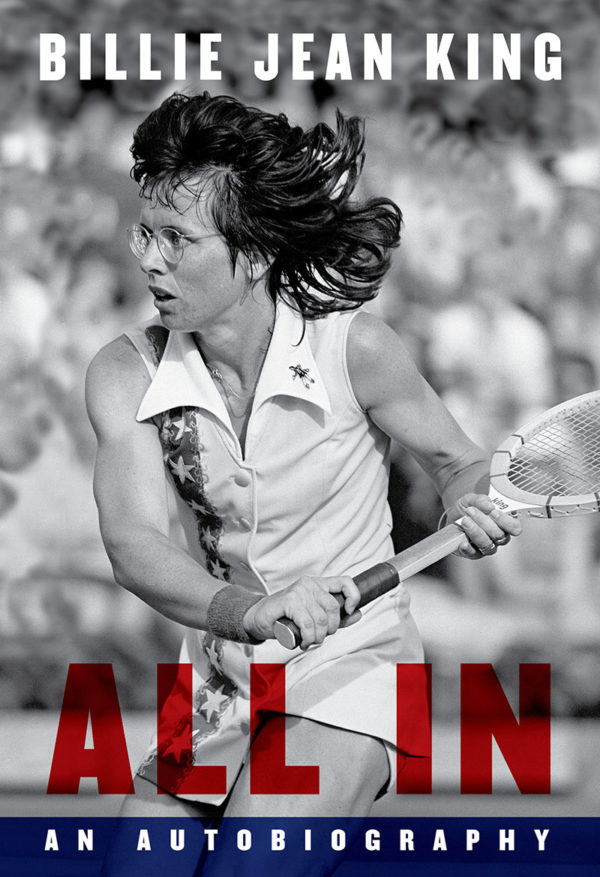

Above: Billie Jean King Shrinks the Court at Wimbledon, 1971. (Getty)