By Lili Anolik

Published Summer 2019

Danielle Collins Is Coming to Take What’s Hers—and Some of What Isn’t.

Can a girl, one ultra-femme in look and manner, be cocksure? If she moves with a lithe feline grace, every gesture sleek, preening, self-contained, is it possible that she also swaggers and struts, chin up, shoulders back, like a gunslinger, like a gangster, like Mick Jagger? Is there a distaff equivalent to macho? It was these thoughts and thoughts of this ilk that were floating through my head the first time I watched Danielle Collins, age 25, from St. Petersburg, Fla., No. 35 in the WTA rankings, play. The occasion: the 2019 Australian Open. The round: fourth. The opponent: former world No. 1, current No. 2 seed, and winner of three Grand Slam championships Angelique Kerber. I’d never even heard of Collins before, understandable since she was 0 and 5 in the majors, if not quite forgivable since she’d clawed her way up from the qualies to the semis of Miami the previous spring, defeating, among others, Venus Williams. (Truth be known, I was only watching this match because I’d stumbled onto it while seeking another, Nadal vs. Berdych, scheduled for that day as well.) And yet here Collins was, not simply beating Kerber but cleaning her clock, the first set a blink-and-you-missed-it 6–0.

I couldn’t believe what I was seeing, except, as it turns out, I hadn’t seen anything yet. On the third point of the second set, Collins hit a drop-shot winner and unleashed a “Come on!” that was closer to a primal scream than a standard-issue exhortation: jaggedly guttural, at least half a dozen os in the on, delivered while looking Kerber dead in the eye, and punctuated with a Byronic shake of the fist, itself a response to the “Come on!” that Kerber had uttered—to herself, at normal volume, with the normal number of os in it, and no fist shake, Byronic or otherwise—the point prior. The emotional release of celebration or castigation at the end of a high-stakes exchange is recognized as a necessity for players, and is accepted, nay, embraced by the vast majority of fans. This, however, was not that. This was a clear instance of one-upmanship (one-up-yours-manship, really), nakedly ad hoc and aggressive and hostile in a way that was rare, practically unheard-of, in professional women’s tennis, which still, even after all these years, retains its patina of decorum: the ladylike skirts; the hand raised in feigned apology following a let ball; the solemn hush of the crowd, as if the contest were taking place in a library rather than a stadium.

The match was over in under an hour, Collins triumphant. She stuck around for the on-court interview, typically where the player you’d seen mere moments ago attempting to dominate, subdue, control, inflict ungodly amounts of pain and suffering would say something the direct opposite of all that, something bland, passive, self-effacing, wouldn’t-hurt-a-fly, something like “I got lucky today,” or “I have the utmost respect for [fill in the blank with the name of the loser],” or the ever-popular “I’m just honored to be here”—you know, the usual humble-pie mumbo jumbo. Only no humble pie for Collins. Not a slice. Not a bite. Not even a crumb. In fact, you could take your humble pie and shove it. When she leaned into the mic, face radiant with sweat and sunshine and bloodlust sated, and said, “I may not have won a Grand Slam match before this, but I gotta tell you, I think it’s going to keep happening,” there was a collective gasp from the stands. Collins talked like she played: not nice.

Collins is the sole reason I’m now regularly tuning in to the WTA, something I haven’t done since 2010, when the spark, not to mention the spunk, went out of the women’s tour—Lindsay Davenport, Justine Henin, and Kim Clijsters retiring or on the verge of; Jennifer Capriati and Monica Seles chased from the game by demons and injuries; Martina Hingis gone, then back, then gone again; Maria Sharapova never quite matching her early brilliance, that Wimbledon title she won so emphatically at 17; Serena Williams distracted or hurt or squashing opponents, sister Venus included, like bugs—and I switched allegiances to the ATP. I’ve been trying to put my finger on what it is about Collins that makes her so intensely watchable—electric, even—a genuine showstopper. She’s a superb athlete, of course, with world-class speed and reflexes, plus serious craft and technical virtuosity. But there are better athletes, and craftier ones with technique still more virtuosic. So that’s not it. Nor is it her backstory, dramatic though it may be: a graduate of the University of Virginia, and the first former women’s collegiate player in the modern era to reach the quarters of a Grand Slam since Lisa Raymond in 2004, the first ever to reach the semis, which she did at that Australian. Yet there are plenty of tennis backstories that are beyond dramatic, are melodramatic: Petra Kvitova surviving a knife attack; Maria Sharapova, Chernobyl; Alexandra Stevenson, the revelation that she’s the secret love child of Dr. J; etc. So that’s not it either.

After racking my brain, I’ve decided that it’s Collins’ raw glandular power that sets her apart. (Those questions I posed in the opener were half joking, but only half.) This power has nothing to do with her prettiness, which is of the long-limbed, blond-haired, honey-skinned, big-smiled, all-American variety. It’s immeasurably enhanced by her prettiness, though.

Collins has created for herself a persona that’s near mythic in its dimensions and implications: that of a wrong-side-of-the-tracks, in-your-face tough chick who’s born ready and up for a fight and out to take what’s hers, and maybe even some of what isn’t. And this persona all but demands a response from you, positive or negative. (At a tournament last fall, after a tense first set, including a heated exchange with the umpire, she returned to the court amidst boos and catcalls, two passionately ambivalent and, I’d argue, entirely characteristic reactions to her. She doesn’t do faux modesty or make excuses and is strikingly free of visible signs of insecurity, and this, coupled with her erotic charisma, can be off-putting to people. She gets under their skin.) Yes, she’s launching a jewelry line. Still, the accessory she wears most proudly is the chip on her shoulder.

Collins is the only child of Cathy, a preschool teacher, and the second child of Walter, a landscaper, whose work ethic Collins speaks of with reverence. (“My dad’s 81. He still mows the lawn every day.”) She’s an autodidact tennis-wise. (“I tried camp but my parents couldn’t really afford it, so I went to the park near our house and played against adults. Adults were nice to me. They’d teach me new stuff, like how to serve. And they were competitive, too.”) She was a very good junior, if not, as she is quick to tell you, a prodigy. (“I was number one in the 18-and-unders by the time I was 14, 15, but I wasn’t a superstar. My parents didn’t have the resources to send me to the international tournaments, and there were other people the USTA prioritized. Those people were able to play junior Wimbledon and junior Australian Open. The USTA chooses players it thinks are going to make it, and I just wasn’t one of them.”) Her college career started inauspiciously, with a benching her freshman year at the University of Florida. (“The coach there [Roland Thornqvist] didn’t like how feisty and confident I was. He maybe viewed me as egotistical.”) She’d turn it around, though, and fast, when she transferred her sophomore year to UVA, where she’d win the NCAA singles title with a broken wrist. (“For a while I had this shooting pain and I thought it was tendonitis. Finally, at the end of the fall semester, I went in for an X-ray. The doctors said, ‘When did you break your wrist?’ They told me that if I didn’t want to be in pain, they had to go in and take out the bone fragment, but it would be a two-month recovery. There was no way I was going to sit out another season, so I’m like, ‘I’ll just play with it.’”) She’d win the title again her senior year. After graduation, she’d make the decision to go pro.

Whether Collins has been overlooked and underestimated her entire tennis life is a matter of debate. What isn’t is that she feels overlooked and underestimated, and resents it hugely, and has used that huge resentment as fuel and a goad, motivation to accomplish her highly improbable goals. She’s got something to prove, and she’s going to prove it or die trying. (Check out her record against fellow Americans, several of whom are former USTA Chosen Ones, if you don’t believe me.) And it’s this combination of desire and desperation, along with an ability to dramatize both these things, that gives her matches an edge and a tension, makes them purely mesmerizing. She puts it all on the line—overtly, blatantly—every time she steps on the court. How can you tear your eyes away?

David Foster Wallace, in his celebrated meditation on Roger Federer, discusses a phenomenon he terms the “Federer Moment.” A Federer Moment occurs when the Swiss hits a shot of such transcendent beauty, artistry, and imagination that the viewer falls to his or her knees, involuntarily assuming a posture of worship and submission—tennis as religious experience. A Collins Moment (my term, not Wallace’s), which isn’t shot-related, which is, in fact, only tangentially tennis-related, occurs when the American does something so rowdy and fearless and appalling and glorious that the viewer can’t credit what he or she has seen, has to rewind, see it again, at which point the viewer finds himself or herself muttering the phrase “Holy shit” over and over—also tennis as religious experience, just of a different sort.

I’ll have a Collins Moment of my own, live and unmediated, at the clay-court event I’m covering in Charleston, S.C. It happens in Collins’ quarterfinal match against reigning Olympic champion Monica Puig. During a changeover, Collins, down 6–3, 3–0 thanks to a bludgeoning performance by Puig, calls for Stijn de Gier, the young Dutchman with whom she’s working, for an on-court coaching session. He jogs to her chair, takes a knee, all ready to dispense words of tactical wisdom. But before he can open his mouth, Collins says, “Just to ask you a question, do you think that my assessment of [Puig] being an aggressive player and kind of going for big shots was an accurate assessment, that since I’ve played her twice, known her my whole life, maybe that’s an accurate assessment?” After semi-conceding the point, de Gier attempts once more to talk strategy. Collins, though, isn’t satisfied.

“[Puig’s] not a defensive player,” says Collins.

De Gier, shaking his head: “I don’t say that she’s a defensive player.”

“Okay, okay, but remember what our disagreement was earlier? I think she’s a pretty aggressive player.”

“I think she’s handling what you’re jamming. She’s handling your pace and redirects [the ball] down the line really good.”

For a second it looks as though Collins is going to let it go, move on. But no, not quite yet. (If she’s going to lose the match, she sure as hell isn’t going to lose the argument, seems to be her attitude.) “So, is [Puig] an aggressive player, would you say?”

Finally de Gier waves the white flag, admits that she was right, he was wrong, does a bit of bowing and scraping. Then and only then is Collins prepared to hear what he has to say.

Holy shit, holy shit, holy shit, holy shit.

My sense is that Collins’ attributes—unabating drive, boundless energy, no-holds-barred determination—are best admired from afar. And yet I can’t resist the chance for an up-close glimpse. Our encounter is set to take place on Monday, April 1, at the tournament just alluded to, the Volvo Car Open on Daniel Island in Charleston. It’s not a match day for Collins, practice only, and we’re scheduled to have lunch once she finishes what is referred to by the tournament’s PR representative as “the Media All Access event,” which sounds intimidatingly modern and elaborately technological but turns out to be an old-fashioned press conference for the top seeds. I almost skip it because it’s off-site, and I’d rather watch tennis. I’m glad I don’t.

True, Collins is last. And I’m stuck listening to the seven players who precede her struggle to answer the question “What series are you currently binge-watching?” without rolling their eyes or making audible scoffing noises. (I never figure out which publication the woman with the blond bouffant posing this query works for, or why she’s so avid for TV-show recommendations.) Still, it’s an opportunity to observe Collins in action off the court.

Like her peers, Collins is dressed in warm-up clothes, though hers aren’t baggy or sweat-stained, are formfitting and fresh. Nor is her hair pulled into a sloppy ponytail or bun, instead cascades silkily down her shoulders and back. Her makeup is subtle, her self-assurance anything but. She looks, in short, polished, professional, camera-ready. And she handles the en masse interview with her patented blend of hardcore ebullience and hardcore abrasiveness. (The highlight, for me, comes when she’s asked who her favorite non-tennis-player athletes are, and she replies, “I’m not really a fan-type person.”) The reporters appear, in equal measures, awed and frightened, as they should.

The press conference breaks up mid-afternoon. I pile into a van along with Collins and her team—de Gier, who introduces himself as Collins’ coach, only to be reintroduced by Collins as her hitting partner, a demotion he takes with a good-natured shrug (he’ll be toast by the time this piece is published, replaced by Betsy Nagelsen McCormack); Marie Halliday and Chris McCormack, both from Collins’ sports agency, GSE Worldwide; and a few others whose names and functions I miss—all young, cute, and boisterous. We stop at Leon’s, a honky-tonk-looking restaurant-bar that used to be an auto-body shop and now specializes in fried chicken and seafood in downtown Charleston.

Collins orders, and I find a table, small, quiet, in a corner. We sit down. I ask questions and she, while dismembering a large lobster with savage delicacy, swirling the meaty bits in a dish of melted butter, answers them. I keep laughing at things she says, though she isn’t trying to be funny, just honest, which is, of course, what makes her funny. For example, when I ask her what the kids were like at that camp her parents sent her to, she says, with no hesitation, “Mean and pathetic.” For another example, when I ask her what her advice is to tennis fans who complain that her behavior during matches is cutthroat and obnoxious, she says, with, if possible, even less hesitation, “Go to the ballet.”

Killer as these responses are, though, they’re just not doing it for me. A foray into autobiography (brief, I promise): I played tennis in college. I’m aware that the No. 4 singles spot at Princeton isn’t on the same planet as the No. 1 singles spot at UVA, but it is in the same galaxy. Which is to say that I have some inkling of what it means that Collins went from being the best player in the NCAA to being one of the best players in the WTA, a progression that would seem natural, almost inevitable to a tennis outsider. Which is to say that I have some inkling of how unnatural, how really, truly extraordinary that progression actually is. I noted this before, yet I did so quickly, casually, like it was no big deal. Now I’m going do so slowly and with emphasis. Collins is the first former women’s collegiate player to reach the semifinals of a Grand Slam in the modern era. Did you catch that? Is it registering? The first ever. What Collins has done is, therefore, literally without precedent. So every question I ask her is in fact the same question in a different guise—how did you do it?

There is no answer, obviously. (Well, there is, but it fails to satisfy as it explains nothing: Collins was able to do it because she’s a once-in-a-generation, never-to-be-repeated mixture of berserk ambition, ferocious need, even more ferocious will, early-childhood trauma, superhuman talent, bulletproof ego, and genetic freakery. In other words, because she’s a star athlete.) Collins, though, as if sensing my frustration, takes a serious crack at giving me one. She wipes her mouth, leans forward in her chair, and says, “All right, here’s when it changed for me. My breakthrough wasn’t at Miami or Indian Wells [a Masters 1000 tournament, which awards $15 million-plus in prize money to players, and where Collins, in 2018, made it to the round of 16]. It was before that. It was at a 25K [a level of tournament on the ITF circuit, the second-tier tour in women’s professional tennis, which awards $25,000 in prize money to players] in Norman, Oklahoma. I was playing in the final against a very rude opponent who was acting like a fool [Sachia Vickery], and I wasn’t playing good tennis. I lost the first set, broke a racquet. There was practically nobody in the stands. Finally, I said to myself, ‘If you don’t want to play 25Ks anymore, you’re going to have to win this 25K. You’re ready for the big stage. Just clean up your game and be done with this crap.’ So I did. I won the match, won the tournament.”

Maybe it’s because Collins’ gaze, trained on mine, is as direct and purely green as that of Margaret Mitchell’s bad-girl heroine, Scarlett O’Hara. Or because her voice bears traces of Scarlett’s Southern accent. Or because we’re in Charleston, hometown of Scarlett’s third husband, Rhett Butler. But as she delivers this monologue, I keep thinking that, with a few tweaks, it could be the “As God is my witness I’ll never be hungry again” monologue delivered by Scarlett just before intermission in Gone With the Wind. It has the same defiance, hyperfeminine and hyper-American, and articulates the same refusal to back off or oblige or be anything short of a hands-down winner. It’s another form of the rebel yell, basically.

The conversation’s over, though we keep it going for an extra minute or two. At last, Collins drops her napkin on the remains of her lobster and we stand from the table. I wish her luck, something she doesn’t need and probably despises, regards as strictly for betas and deadbeats. But she thanks me anyway, which I find moving—a polite gesture from a willfully impolite person. Then, after a quick handshake, she walks over to her team, and I to the Uber waiting outside the restaurant.

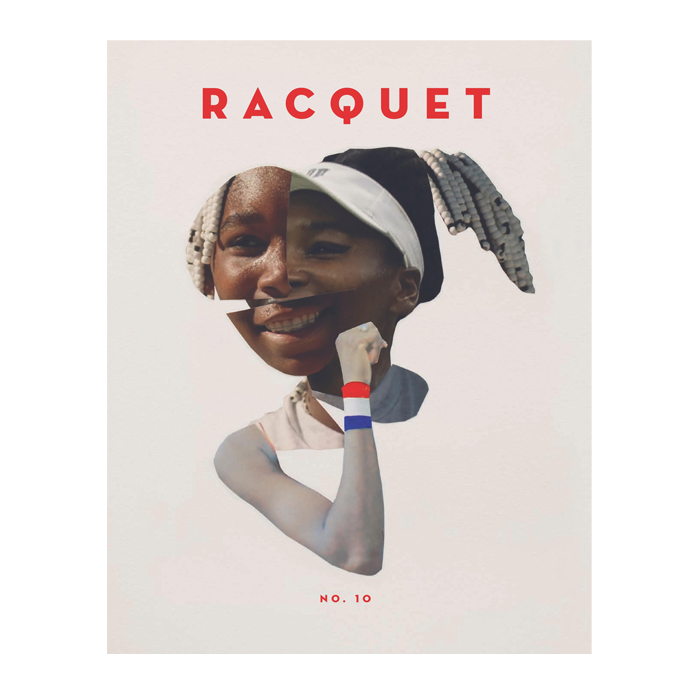

Above: They don’t call her “Dan-yell” for nothing. (Getty)