By Joel Drucker

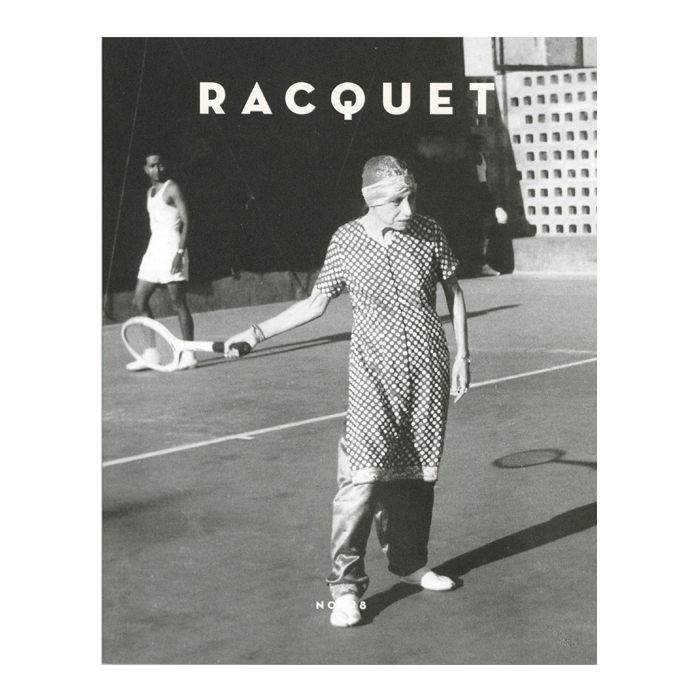

Like Her Mother Pauline Betz, the Poet Kim Addonizio Is a Champion—Albeit of a Totally Different Stripe.

Kim Addonizio isn’t sure if it’s been three or even five years since she last hit a tennis ball. But on this spring afternoon in Berkeley, Calif., you can see in one minute that she has been taught to play tennis properly. There’s a graceful turn of hips and shoulders, racquet ready to smoothly shape the swing. When a looping topspin drive arcs her way, Kim adjusts, finds the proper spacing, and drives the ball deep. Though she’s rarely played tournaments, tennis is in Kim’s blood. “I just feel good when I’m around a tennis court,” she says.

Kim’s return to tennis is happening at the Berkeley Tennis Club, a Northern California venue just under two miles from her home in Oakland. Hall of Famers Helen Wills, Don Budge, and Billie Jean King are among the notables who have played there frequently. Only later will Kim learn that her mother, Pauline Betz, also competed there several times. No wonder Kim has such fine strokes. You might too if the only time your mother played Wimbledon, she won it.

Fuzzy and vague are words that best describe how we come to understand the lives of our parents. Scattered conversations, forgotten amid the tangle of daily activities. Faded black-and-white photos. Disparate, undocumented, inaccurate memories. The picture is impossible to complete, distant in time, children and parents often more eager to move forward than look back. It’s also usually highly private, distant from public history, perhaps even more so for a generation of mothers who primarily devoted themselves to matters of family over generating headlines.

Kim’s mother’s story was very different. On Sept. 2, 1945, in Tokyo Bay, Japan, General Douglas MacArthur presided over the conclusion of World War II. Upon the Japanese government signing the surrender papers, MacArthur gave a short speech he concluded with five sonorous words: “These proceedings are now closed.”

That same day, more than 6,700 miles east of Tokyo, Pauline entered the stadium court of the West Side Tennis Club in Forest Hills, N.Y., to play the finals of the U.S. Nationals (what’s now the US Open) for the fifth straight year. She’d won it three straight times—all during World War II.

Prior to the match, a small ceremony was held to mark the end of the war. The national anthem was played. The West Side Tennis Club’s president, P. Schuyler Van Bloem, made a short statement. As the crowd stood, Navy chaplain R. Frank Crawley led a prayer.

Pauline’s opponent was Sarah Palfrey Cooke, a feisty net-rusher from Boston. Cooke had also been the last person to beat Pauline at Forest Hills, taking her out in the ’41 final. Though Pauline won the first set and served at 4–3 in the third, a four-peat proved elusive. In the heady prose of his day, longstanding New York Times tennis reporter Allison Danzig wrote, “In a beautifully fought final that had the 10,000 spectators in a state of almost breathless excitement, with the outcome in doubt to the last stroke, Mrs. Cooke rose to her most shining moments when her fortunes seemed to be ebbing fast, to snatch victory from a valiant rival, through the sheer brilliance and enterprise of her attack. The score was 3–6, 8–6, 6–4.”

“I didn’t know about that,” says Kim. Of course. Pauline did not care to even mention her losses. She preferred avenging them. With wartime conditions having canceled Wimbledon, Roland-Garros, and the Australian Championships for six years, those events were all set to resume in 1946. Pauline hungered to make a global statement. Following the loss to Cooke, she commenced work with Eleanor “Teach” Tennant, a prominent instructor who’d coached the last prewar Wimbledon singles champions, Bobby Riggs and Alice Marble. Over the course of hours with Tennant, Pauline improved her forehand and serve.

In that first postwar year, Pauline proved emphatically that she’d been the best amateur of the decade. Seeded first at Wimbledon, she won the title without the loss of a set, then headed to Roland-Garros (played after Wimbledon in ’46 and ‘47) and lost in the finals to Margaret Osborne, 1–6, 8–6, 7–5, after holding two match points.

As the U.S. Nationals got underway in August, Pauline was featured on the cover of the Sept. 2 edition of Time, a magazine that was then America’s premier news publication. “The thing that makes her go is a terrifying determination not to lose at anything—tennis or checkers, or gin rummy at a cent a point,” read the piece. “Competition is the spice of her life.”

Pauline’s signature shot was an elegant one-handed backhand, a forceful drive she’d modeled after the great one created by a player four years her elder, Don Budge. She was also extremely swift and, best of all, composed under pressure. “Principally because of her green eyes, she seems to have a ready-to-pounce, feline quality,” read the Time story. “A straightening of her shoulders is a characteristic mannerism—a squaring away that seems to symbolize in an otherwise relaxed girl, a won’t be-beat spirit.”

In the finals of the ’46 U.S. Nationals, Pauline was down 5–1 in the first set to Doris Hart, a player who’d eventually become the first of only three players to win the singles, doubles, and mixed at all four majors. “She was serving and volleying so severely that I could not take the offensive away from her,” wrote Pauline in her 1947 autobiography, Wings on My Tennis Shoes, “and there was nothing to do but keep scrambling and hoping that the storm of aces would abate.” It did. Pauline rallied to win the opener 11–9 and the second set 6–3.

Long before the word charisma entered the cultural lexicon, Pauline had it in abundance. A tobacco advertisement from the ’50s shows her in stylish repose, bathed in sunlight, clad in crisp white tennis clothes, wood racquet cradled across her legs, a cigarette in a raised right hand, Pauline expressing appreciation for the Camel brand alongside baseball great Mickey Mantle, Olympic diver Zoe Ann Olsen, and golfer Julius Boros. “The funny thing,” says Kim, “is that my mother never smoked.”

Pauline dated heavyweight boxing champion Jack Dempsey and Oscar-winning actor Spencer Tracy; the latter, the joke went, in between his extramarital liaisons with another Hollywood notable, Katharine Hepburn. “TO THE CHAMP FROM SILVERTOP,” read the inscription on a gold bracelet Tracy gave Pauline. One of her best friends was Barbara Hutton, an heiress whose seven husbands included actor Cary Grant and tennis great Gottfried von Cramm. Just after the war, Pauline was often the tennis legend in residence at the Racquet Club, a stylish venue located in Palm Springs, Calif., palling around, as the parlance went, with prominent comedians Groucho Marx and Jack Benny, as well as many other Hollywood notables.

Pauline’s husband, Bob Addie, loved to tell the story about the time the two of them dined at an exclusive New York venue, the Stork Club, and were seated in a special room reserved for notables. When Bob returned from the bathroom, he was denied entry to that area. But an intervention from Pauline overturned the verdict. At the high-water mark of what Time had christened “The American Century,” Pauline stood atop the tennis mountain.

***

This is something different from a parental legacy of crumbling photos and vague tales. This is a vivid and lively public narrative, of a mother who once upon a time flew in rare air—a feminist superstar before such argot existed, first-class citizen in a pre–Jet Age version of the Jet Set.

What kind of fingerprints does that leave? Upon hearing that a Wimbledon champion’s son was on the grounds of his club, a member once said, “I want to meet him so I can tell him how much I admire his dad.” Who wishes to live as a messenger? Should the child have carried a briefcase of autographed 8×10 glossies? In the wake of Pauline’s fabled success, what story did her only daughter go on to tell?

Kim deeply understands the power of a tale. She is a prominent poet, author of seven poetry collections, two novels, two story collections, and two books on writing poetry. In 2000, Kim was nominated for a National Book Award. A 2008 article called her “a rock star, the Chrissie Hynde of iambic pentameter—especially in San Francisco, where poetry really does constitute the soul of the city.”

Mother, world-class athlete, and teacher. Daughter, world-class poet, and teacher. From a distance, a contrast between athlete in motion and artist in reflection. Up close, though, linked by ambition, desire, and the persistence required to thrive as a vagabond-like performer, uncertain of where the next check will come from, pragmatically aware that instruction must pay the bills too. Most of all, each subtly rebellious, determined to shape her own destiny.

Kim’s description of poetry is similar to a definition of tennis: “Thought in action.” In “The Moment,” Kim describes the aging Pauline:

I saw for the first time old age, decline, the inevitable easing

toward death. Once in the car, though,

settled behind the wheel, backing out and heading for the steady

traffic on the highway,

she was herself again, my mother as I’d always known her: getting

older, to be sure,

in her seventies now, but still vital, still the athlete she’d been all

her life; jogging, golf,

tennis especially—the sport she’d excelled at, racking up

championships—they were as natural

to her as breath.

Born in 1954, the only girl in a family of five children, Kim grew up in Bethesda, Md. Pauline taught tennis, over the course of 40 years working at local venues Edgemoor Tennis Club, Cabin John Regional Park, and Sidwell Friends, the latter a prestigious private school. Though notables Pauline spent time on court with included future world-class players Donald Dell, his brother Dick, Harold Solomon, and Donna Floyd Fales, she far preferred teaching beginners. Bob worked for The Washington Post as a prominent sports columnist who, as was customary well into the ’60s, cavorted with his subjects in all sorts of discreet and amusing ways. If Pauline was the fighter in the quietly confident way appropriate to athletes of her generation, Bob was the lover, a romantic who admired athletic prowess and savored his role as its chronicler. “Talent is what mattered most in our family,” says Kim’s brother Gary, himself a college tennis player who in his teens joined Pauline as an instructor. “If you did something, the message was that you better be great at it.”

By Kim’s estimate, the Addie house had at least six working TV sets, each usually airing a sports event. While Kim enjoyed tennis and spent summers as an instructor at Pauline’s tennis camp, she far preferred reading. The local library permitted a cardholder to take out only three books at a time. But Kim would borrow her brothers’ cards to obtain more. Kim’s favorites included a pair of French philosophers, Jean-Paul Sartre and Albert Camus. “I was a little existentialist,” she says. “I was also a little snob, thinking that the life of the mind was the better way to live than be obsessed with sports like everyone else was in my family. Only later did I value the importance of the body, thanks in many ways to my mom.”

By her early 20s, Kim had twice dropped out of college. On a whim, she headed with a friend to San Francisco, keen to become a singer-songwriter. Kim changed her name during that time, too, several years after Pauline’s mother ardently pointed to a newspaper article about a corrupt Newark mayor named Hugh Addonizio. “She told me, ‘That’s your family!’” said Kim. “He was a cousin of my dad. I liked the sound of the name and the connection to my Italian heritage.” There she was, neither Betz nor Addie.

The shift from music to poetry came when Kim stumbled across a well-designed book featuring the poetry of Sylvia Plath. “It totally took off the top of my head,” says Kim. Studying at San Francisco State University, she changed her major to creative writing, her work ethic inspired by Bob’s example. A newspaper columnist is an in-demand lover, constantly summoned to bed and the demand to perform, again and again and again under deadline pressure. The work pattern for Bob was to attend a game late into the night and, the next morning, park his butt at the typewriter. Bob had long encouraged his book-loving daughter. On his deathbed, in 1982, Bob gave Kim a one-word command: “Write!”

To fund her dreams, Kim held jobs as a fry cook at a San Francisco tourist spot, bookkeeper for an auto supply company, employee at a sporting goods store, where one of her tasks was to string racquets for $1.80 an hour. She continued to play tennis at San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park. But did Kim have the goods for a career in literature? Jogging through the park one day, she said to herself, “I’ll never have a book, I’ll never have a book.”

Pauline during this time wondered what was to come of her daughter. “She thought I was kind of aimless,” says Kim. But Pauline was as far as it got from a hands-on mother, her children eating their share of TV dinners. When Gary entered a national 12-and-under tournament, he arranged his own flight and accommodations and trekked to the tournament by himself. As Kim says about Pauline, “She did not get the standard mommy chip.”

But don’t think of Kim as a rebel. She loved her parents. But like them, she was an independent, free soul, out to create a path all her own just as Bob and Pauline had. “You do not want to be like your mother,” writes Kim, “achieving early and astonishing athletic success, shaking hands with British monarchs and dating movie stars, and then getting married and having a bunch of useless, unruly children. You want to be Wendy: a hard-drinking, cock-sucking beauty with creamy skin and really good hair.” This is typical of the matter-of-fact way Kim describes her various forays and attitudes. After all, she comes from a line of self-assured women always willing to speak and act on their terms rather than comply with society’s limits and expectations. “There seems to be a contrarian streak in the females in my family,” says Kim’s daughter, actress Aya Cash. And it didn’t start with Pauline.

***

Nicknamed “Bobbie” by a sister who mispronounced “baby,” Pauline was born in Dayton, Ohio, in 1919. The Betz family moved to Los Angeles when she was 8. Little is spoken of her father. Pauline’s mother, Stella, a physical education teacher with her own brand of zeal, was the primary influence in her life. Encouraged by Stella, “Bobbie” played tons of baseball, basketball, and football. Graced with extraordinary balance, speed, and agility, Pauline was a natural athlete. “I was ten before my family could make up its mind as to whether I was a cat or human,” she wrote. “I could spot any alley cat three leaps and beat him up a tree. Since the future for such proficiencies is at best unproductive, Mother wilily began to interest me in tennis.”

Year-round sunshine and a vast network of public courts made Los Angeles a tennis mecca. By her teens, Pauline had the fever, graduating from hours on the backboard to even more time spent in competition at public parks such as Griffith Park, L.A.’s equivalent of Golden Gate Park and New York’s Central Park. She also played at two of the area’s more exclusive venues, the Los Angeles Tennis Club and the Beverly Hills Tennis Club. One of Pauline’s practice partners was an enthusiastic boy five years younger than her who lived nearby named John Edward “Budge” Patty. In 1946, Patty and Pauline took the mixed doubles title at Roland-Garros without losing a set. Four years later, Patty won the singles at Roland-Garros and Wimbledon.

As Pauline came of age in the ’30s and ’40s amid the austerity of the Depression and the stress of World War II, a new American female archetype emerged, a woman scarcely submissive or coquettish but instead subtly rebellious, assertive, cheeky. “With the development of talking pictures, there came about a female character who could talk well, talk funny, and talk back to guys,” says film historian David Thomson. “This was a tough dame who was attractive, smart, and also a real competitor.” Sharp-edged actresses Barbara Stanwyck and Katharine Hepburn were avatars of this pre-feminist ethos. The Depression had made them tough. World War II put even more women into the work force. What during this uncertain time necessarily gave men supreme power?

Pauline was the racquet-toting personification of this shift, far more eager to perform and be judged on her terms than comply with societal demands. A captivating public speaker, often ready with a disarming quip, later in life she said her fantasy career was to be a stand-up comic. At a time when women rarely went to college, Pauline’s tennis earned her a scholarship to Rollins College, a Florida-based school where Pauline was good enough to play on the men’s team. She completed a degree in 1943, an incredibly rare achievement for a top women’s tennis player in any era.

Tennis then being mostly an amateur sport, Pauline and her peers were forbidden to be given prize money. Instead, they were compensated under the table, in the form of so-called “expenses.” It was all random, even the very best players subject to the whims of various tennis officials. The week after Pauline won Wimbledon, she was given $5 a day to play an event in Sweden. One year, immediately after winning Forest Hills, she swiftly returned to Los Angeles to resume her job as a waitress. Traversing the country to compete, often with Stella, Pauline was masterful at making the most of the tiny sums she was given, be it a dime for three bananas, sleeping on the beach during Forest Hills, or sharing a precious jar of peanut butter and a handful of crackers. Pauline joked she could manage all this so well because she’d majored in economics.

Prior to World War II, the headliners of women’s tennis were the flamboyant Suzanne Lenglen, cucumber-cool Helen Wills, gritty Alice Marble. Soon after the war ended came the ’50s, the marquee featuring the dominant Maureen Connolly, the first woman to capture all four majors in a calendar year, and the breakthrough triumphs of Althea Gibson, tennis’ first black champion. But because so many of Pauline’s finest moments came amid the war, her excellence has long lingered in the shadows of history.

During Pauline’s glory years, President Franklin D. Roosevelt spoke about the value of sports as a vital tool to boost morale and maintain continuity. But of course, amid wartime footing, there was only so much cultural capacity for sports as soldiers crisscrossed the world, manufacturers retooled and revved up, communities rationed and struggled. Tennis, far less popular then than it later became, circled in its own tiny orbit. Women players occupied one even smaller. From 1943 to ’45, the U.S. Nationals women’s singles draw featured only 32 players. Examining press coverage, Pauline wrote that “Women start out under the terrific handicap of being women athletes. Our tennis matches are the signal to empty the place in five minutes—we’re the fire alarm of tennis.”

But the competition remained fierce. Every woman Pauline played in those U.S. finals—Cooke, Hart, Osborne, Louise Brough—won multiple Grand Slam singles and doubles titles and was inducted into the International Tennis Hall of Fame. Consider this retinue of skilled athletes a tennis version of the 1992 movie about women’s baseball during World War II, A League of Their Own. By day, they politely tried to knock one another’s heads off, practiced together, and paired up for doubles at one patrician club after another. By night, they were often roommates in quarters that ranged from a member’s spacious mansion to sleeping bags inside an attic at the club. Decades later, at exclusive tennis alumni spots like Wimbledon’s Last Eight Club, Pauline relished the chance to chide a rival such as Brough (a.k.a. “Broughie”) about her pitiful second serve. Brough countered: Well, what about your overhead, Pauline? And the two shared the laugh earned only through the intimacy of competition.

As 1946 began, with Cooke having retired, Pauline conclusively ruled the roost, to the point that the group of American women’s players who traveled to Europe in the spring of ’46 was nicknamed “The Betz Club.” Pauline’s ’46 win at Forest Hills meant she’d reached the U.S. women’s singles final six straight times. Only Chris Evert has since matched that feat.

By the spring of 1947, Pauline had won 39 consecutive matches. Still just 27 years old, she was primed to defend at Wimbledon, earn the Roland-Garros victory that had slipped through her fingers the previous summer, and once again prove supreme on native grounds.

But then came what Jack Kramer later called one of the biggest crimes in tennis history. In early 1947, Elwood Cooke, a fine player who was also Cooke’s husband, began to explore the possibility of several clubs staging professional women’s events. This was nothing more than a probe, far less vocal or committed than the way stars like Budge and Riggs had overtly proclaimed their intention to eventually turn pro while they were still amateurs.

For reasons that remain uncertain, the United States Lawn Tennis Association took umbrage at Cooke’s action. Pauline, in Monte Carlo for a tournament, was informed she could no longer take expense money, that her status as a player was uncertain and the issue could not even be addressed until after the U.S. Nationals. More bluntly, she had been suspended—banned from that year’s Wimbledon, Roland-Garros, Forest Hills, and all other amateur tournaments.

Pushed to the edge, Pauline opted to leap. On May 5, 1947, Pauline and Sarah announced they had turned pro and were set to play matches that month throughout the South. There was also a European tour that summer alongside Budge and Riggs. To spark things up, Pauline unveiled “Susie Glutz,” a disheveled character with warped racquet, rain hat, and size 40 shorts who would beg Sarah to correct her pitiful form. While a far cry from such regal venues as the All England Club and the West Side Tennis Club, the rewards were far greater. That first year, Pauline made $10,000, a fine sum in those days when gasoline cost 23 cents per gallon.

But no matter what the gender, pro tennis struggled to generate traction. Not until 1950, a year after she’d married Bob, did Pauline tour again, this time after being offered $500 to $600 a week by promoters Kramer and Riggs. The opponent was Gertrude “Gussie” Moran. In 1949, at Wimbledon, Moran made worldwide headlines when she wore ruffled lace panties underneath her tennis skirt. Though an excellent player—Gussie had extended Pauline to three sets in the quarters of the ’46 U.S. Nationals—when it came to day in and day out competition, Pauline was far superior. Pauline rolled through their first match, 6–0, 6–3, in 33 minutes. Not one to be outdone in the fashion department, Pauline that night entered the court in silver lamé shorts and a bright pink sweater, then changed into a wild zebra outfit for the doubles.

That first evening at Madison Square Garden drew only 6,526 attendees and generated a meager $16,960 at the gate, by far the smallest opening night Kramer could remember. As Pauline pummeled Gussie night after night, Riggs suggested Pauline find a way to sprain an ankle and even offered to give her a car in exchange for giving Moran a chance to win. An insulted Pauline burst into tears. As a concession, Pauline took some speed off her shots and aimed them farther from the lines. But this only made her more consistent, triggering increased errors from Moran. Finally, one night in Milwaukee, Moran earned a victory, at which point Pauline screamed at Riggs, “Well, I guess you’re satisfied now.” Years later, Kramer said Pauline was a tremendous competitor and the fastest player he’d ever seen, a speed Gary compares to the gazelle-like swiftness of Steffi Graf.

Through the rest of the ’50s, Pauline only competed sporadically, the world hardly receptive to professional women’s tennis. But there came occasional moments. In 1959, the year she turned 40, Pauline was five months pregnant and earned a win over Gibson, who’d just turned pro after winning Wimbledon and the U.S. Nationals two straight times. “Pauline’s competitive skills were just remarkable,” says Rob Arner, a near-brother of the family who taught with Pauline for many years and partnered with her for many a doubles match. Arner notes how in tight situations Pauline’s focus would narrow, leading to anything from a dart-like return to a superb retrieval or a pinpoint lob.

Though not as obviously competitive as tennis, Kim’s world too is flavored by public forms of ambition and appraisal. “Writing is fighting” goes the motto of Kim’s fellow Oakland resident Ishmael Reed. She competes for grants, fellowships, and critical acceptance in a profession where evaluation is far more subjective than the performance-based world of tennis. The National Endowment for the Arts has twice awarded Kim fellowships worth $20,000. As Pauline did during her playing days, Kim treks from city to city, in her case hoping to attract a reasonable fee for poetry readings. It was hard for Pauline to grasp that this was a legitimate career, much less a calling. Hearing an update once from Kim on her literary progress, Pauline asked, “They pay you for that?” But Kim was also told by Pauline’s friends that her mother talked about Kim constantly.

In a way that echoed how Pauline took the bat out of the USLTA’s hands and turned pro instantly rather than submit to haughty authority figures, Kim faced a hostile situation and opted to turn it into an advantage. When her collection Tell Me was being considered for a National Book Award, Kim learned that one of the judges had called her nothing more than “Charles Bukowski in a sundress.” This was a reference to a popular California-based writer often derided as an indulgent, drunk misogynist. Rather than shrivel from the judge’s dismissive comment, Kim embraced it. Thus came her 2016 book, Bukowski in a Sundress: Confessions from a Writing Life, adorned with a cover shot of a tattooed Kim wearing fishnet stockings and sipping from a large goblet. In the title essay, Kim writes, “Frankly, I’d have preferred a different, though equally nuanced, characterization of my work—say, ‘Gerald Manley Hopkins in a bomber jacket,’ or ‘Walt Whitman in a sparkly tutu,’ or possibly ‘Emily Dickinson with a strap-on.’” The Publisher’s Weekly review called Bukowski in a Sundress “funny, frank, vulgar, and just a little bit vulnerable.”

It’s unclear how Pauline reacted to a daughter with a capacity for wit and sexual candor far different from the subtle innuendos favored by her generation. Given the circles Pauline had run in as athlete, celebrity, and wife of a newspaperman, she surely wasn’t a prude. But again, recall that the motherly part of parenthood was a foreign language for her, be it as chef, chauffeur, or life manager. “Her ambition wasn’t to push her kids,” says Aya. “She didn’t see her kids as a reflection of herself, which is actually healthy.” If at one level Pauline raised Kim and her four brothers by example, in another sense she largely occupied her own world. What mattered most to Pauline was the single-minded pursuit of excellence, be it in real estate, automotive repair, computers, music, or her second-best mode of competition, bridge, where Pauline became a life master.

Though Kim and Gary both say that the last thing Pauline ever wanted to do was come across as arrogant, unquestionably she was self-assured, striking truth of the notion that confidence is belief based on data. Gary loved to watch tennis matches with her, the eyes of a champion attuned to factors that eluded even skilled civilians. Says Gary, “It would be 3-all in the first set and I’d say, ‘Mom, looks pretty close.’ She’d say, ‘No way. This one has 3 and 2 written all over it.’ And she’d always be right.” Well into her 70s, asked by Aya how she’d fare versus the latest crop of pros, Pauline had no doubt she’d emerge triumphant. As Pauline once said, “If I were a second-rater, I’d quit.” So perhaps what Pauline wanted most for Kim was what she’d had: greatness.

Dedication and craft, love and memory merge powerfully when Kim writes about Pauline: “Remember how fast she was on the tennis court, how she always jogged up stairs. Remember her enjoying a single bourbon and Coke almost every night with a bag of Fritos.”

Those words came as Kim reflected on the painful final decade of Pauline’s life. “Until she was nearly 80, she was a poster child for aging well,” says Kim. “She was going to live forever.” But then came illness, Pauline diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease, her health eroding year by year. Gary, based in Maryland, looked after Pauline and visited her every day at Summerville, an assisted-living facility. Kim flew in from California, intermittent witness to a harsh decline.

“My mother has developed an unholy love for Cheez-Its,” writes Kim in an essay revolving around the quest to persuade a bedridden Pauline to get a flu shot. “If she doesn’t have at least a couple of boxes, she gets that look in her eye, the look of an addict down to the last of the heroin, filled with anxiety that there won’t be a wake-up shot for the next morning.”

The juxtaposition with Pauline’s life prior to Parkinson’s is poignant. “When she took me to London in the eighties for an event honoring the female Wimbledon champions, we ate strawberries and clotted cream with the Duke and Duchess of Kent,” writes Kim. “There were daily rides to the tournament in the special green Wimbledon minicars, and chats with Martina Navratilova. Now there is Summerville, and fumbling at the buttons on her sweater. Now there are Cheez-Its.”

Pauline died on May 31, 2011, at the age of 91. Four years later, Kim wrote a piece for The New York Times about one of Pauline’s last public appearances, when the tennis center she’d taught at for years had been renamed for her. “I stand on your shoulders, Pauline,” said attendee Billie Jean King. Pauline, wrote Kim, “spent the day in a wheelchair, sitting in front of the crowd on a stage that had been set up on one of the indoor courts, while people talked about her and her contributions to tennis. And when it was her turn to give a speech, she was gracious and funny.”

Racquet in hand, Pauline had soared. But Kim brought her mother’s humanity back to the earth, the journey from health to death arguably more meaningful than the one Pauline had taken from a backboard in Depression-era Los Angeles to Centre Court at Wimbledon. The entire spectrum inspired Kim. “She showed me what it meant to be excellent at something,” says Kim, “that being great meant hitting on a garage wall at 6 a.m.”

Yet much as Kim always knew Pauline loved her, not until Kim was nearly 40 did Pauline overtly acknowledge something superlative that she’d done. On that occasion, Kim took Pauline to New York to see her conduct a poetry reading. Hundreds of people filled the auditorium and paid rapt attention to Kim’s verse—including a spellbound Pauline. Afterward, she said to Kim, “You had them in the palm of your hand. Doesn’t that feel good?”

What had Pauline at last admired? Would she have been so dazzled had Kim finished preparing a tax return, launched a new software product, examined children for eight hours? Or was it that her daughter was also now a fellow star performer? Who knows? In that moment, Pauline recognized her daughter for what each was: a champion.

Joel Drucker is a frequent contributor to Racquet and is a historian-at-large for the International Tennis Hall of Fame.