By Giri Nathan

It is said, at least by fortune cookies, that every crisis is an opportunity in disguise. Maybe Novak Djokovic read this on a little paper slip in February and realized that the present health crisis was indeed an enormous opportunity…to reveal himself as a clown, emphatically, repeatedly, and internationally, until there was absolutely no question as to how big a clown he is. Now he is also a clown with COVID-19.

The facts of Novak Djokovic’s clownhood have been sitting out in plain sight for some time. Real heads knew about the infamous “bread on forearm” test for gluten intolerance, for one, and the telekinesis belief, plus the commitment to “natural healing.” There just wasn’t any particular reason to talk about it. We were distracted by all the world-historically good tennis he was playing. And perhaps he was too busy actually playing all that tennis to sit down and disseminate his beliefs. But the suspension of the tour relieved him of that burden, and against the backdrop of an international discussion of public health, he decided to let the takes fly. And what did we learn? That he was “opposed to vaccination.” That polluted water could be purified with positive emotion. That a cretin hawking “Advanced Brain Nutrients” was worthy of his platform. That the US Open was being “extreme” by not letting players roll in with their usual entourage.

And, fatefully, we learned that Novak Djokovic thought he could organize an international exhibition tournament without taking any health precautions and things would go fine. The impact of the first few gaffes is more nebulous—maybe some people out there developed worse beliefs about public health, but who knows?—but this last one had clear and unignorable harms.

Djokovic had grand visions for his Adria Tour. Though it only made it to two, it was intended to pass through cities in four(!) different countries: Serbia, Croatia, Montenegro, Bosnia. Matches were played in an abbreviated format, with players like Djokovic, Dominic Thiem, Sascha Zverev, Grigor Dimitrov, Victor Troicki, Damir Dzumhur. Proceeds were intended to go to “humanitarian projects in the region,” per a Djokovic statement, which is especially rich in retrospect.

Unlike surreal fanless exhibitions conducted elsewhere on earth, the Adria Tour looked like it was held in the peaceful obliviousness of some other planet. Djokovic maintained that the event fell in line with Serbian guidelines, a claim that has come under fire, and that also makes you wonder bleakly about his sheer force of personality back home. There was no testing of players before any leg of the tournament. Stadiums were packed. No face masks to speak of. Ball people and linespeople operated just as they did in the before times. Journalists crowded into enclosed press conferences. Fans mugged with players for photo ops. Players hugged, shook hands, bumped bodies in pickup soccer and basketball, hollered shirtless at each other at an after-party in a Belgrade club. Even on a cynical cost-benefit analysis, was any of this really worth it? All that risk to watch Novak Djokovic beat up on the world No. 299? To watch Sascha Zverev double-fault 12 times? (Okay, that was actually kind of captivating.) To round up a bunch of colleagues and damply gyrate on a stage?

The tour didn’t last long anyway. Grigor Dimitrov was feeling ill enough toward the end of the last match in Zadar that it showed in his play. He didn’t want to shake hands with his last opponent. He tested positive for COVID-19. Other players present in Zadar got tested, and Borna Coric and Viktor Troicki said they tested positive too. Marin Cilic, Andrey Rublev, and Sascha Zverev tested negative and said they would follow self-isolating procedures. Meanwhile, Djokovic did not get tested in Zadar, opting to wait until he had traveled back to Serbia—per his agent, because “he did not feel any symptoms”—only to reveal that both he and his wife tested positive. Djokovic has since said that the Adria Tour was a mistake. “I am so deeply sorry that our tournament has caused harm. Everything the organizers and I did the past month, we did with a pure heart and sincere intentions,” he wrote. “We were wrong and it was too soon. I can’t express how sorry I am for this and every case of infection.”

The door is now open for Djokovic to do actual “humanitarianism.” In his response he committed to “sharing health resources” with Belgrade and Zadar. If that means dipping into his riches to fund relief efforts, then maybe he can begin to offset the evils of getting thousands of people to congregate in the presence of coronavirus. But helping out might require some ideological concession on Djokovic’s part: that a pandemic requires something more than positivity to overcome, and that modern medicine might have something to offer in the fight.

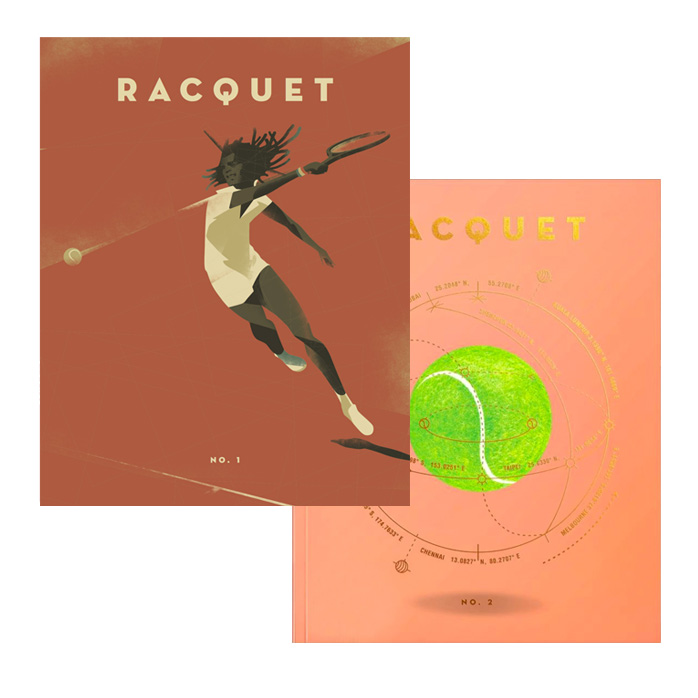

Buy Now

Issue Nos. 1-2

Copies of Racquet No. 1, our launch issue, are almost sold out. Order a copy bundled with our sophomore effort for just $25. *Free shipping to domestic USA*