By Andrew Eccles

In a bold annual tradition dating back to 1980, the French Tennis Federation offers an artist carte blanche to create Roland-Garros’ official poster—a unique reinvention of the identity of the event. In 2021, that honor fell to young figurative painter Jean Claracq. What Claracq unveiled was a poster that the Federation describes as “a singular piece that incorporates one of the most important new features at this year’s tournament: the introduction of night sessions.”

What I saw was something entirely more radical.

What I saw was gay.

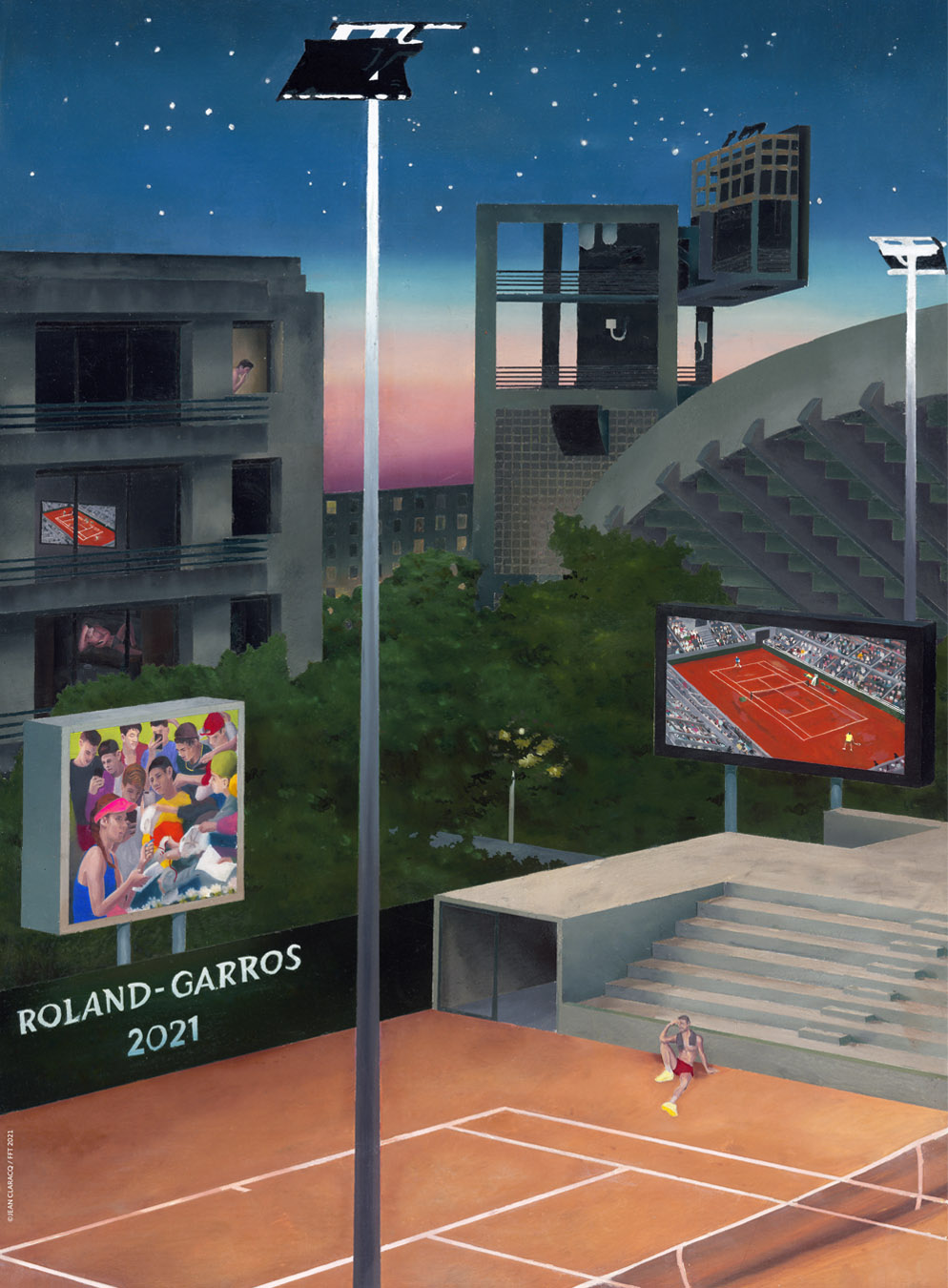

The first figure you notice in Claracq’s poster sits alone on the clay of an empty court, Stade Suzanne Lenglen towering behind him. He has removed his shirt and draped it over his shoulders. One leg is outstretched, one hand rests on his forehead. He looks tired. It is nighttime in Paris, and the man is illuminated by floodlights and two large screens.

On one of the screens is a crowd surrounding a victorious player, the only woman on the poster, as she signs autographs. Each member of the crowd is a young man, and though we see the backs of some heads there is a prominent group of eight split into distinct pairs, each leaning intimately into their partner, sharing the screens of their phones as they attempt to snap a photo of their idol. They are all young, and slim, with perfectly styled hair.

These are gay men. This is a gaggle of twinks.

These are gay men whose first love is women’s tennis. These are gay men whose collective favorite color is WTA purple. I recognize these men because I’ve met these men. It was this group of men who ejected me from their party bus on the way home from a Kacey Musgraves concert when their leader insisted no guests could ride. It’s with this group of men that I’ve lifted countless dollars in the air awaiting the hands of a lip-synching drag queen dressed as a haunted house. I love these men. They’re messy and sometimes mean for the hell of it but ultimately good, actually.

They are not the only men I recognize in this poster. Behind the screen, we see inside an apartment building. Through one window is a large TV beaming live tennis. Through the window below we discover a man reclined on his couch, his slender body illuminated by the light of his phone. He wears only black briefs. He is enticing. To the untrained eye, he is perhaps watching a match on his phone—just another sports fan. To my gay eyes it is distinctly the posture of a man scrolling through a hookup app. Roland-Garros put Grindr on their poster.

I can think of nothing more Parisian than celebrating this simple act of rebellious lust. Somewhere in the culture we’ve mistranslated Paris’ art, fashion, sex, and food into softcore romantic delights rather than the naked, transgressive acts of creation they are. At Roland-Garros, the same mistranslation applies. The French Open is not elegant. Clay-court tennis is dirty. You must win this tournament ugly, your clothes stained brown and your thighs aching from constant imbalance.

There can be no better mascot for this delectable filth than the clay-orange mask of the Grindr app, and it feels right that this ambassador from another world should make an appearance in tennis. Tennis is a gay sport.

Tennis is not gay solely because of our great gay champions, Martina Navratilova and Billie Jean King the most famous of all, but also because of the foundations of the game itself. Tennis is a you-against-the-world battle for self-actualization. It’s a sport designed for individual flair—finding new ways of ecstatically swinging your arm through the air, of dancing your feet, of outsmarting your opponent with ruthless wit. It’s a sport for people who understand what it is to fight and win and lose alone.

That is not all of what tennis is, nor is it close to all of what being gay is. But let me be very clear: Tennis is gay, gay, gay.

Back to that first enigmatic figure, alone on the clay. He is the first man you notice because he sits isolated, vulnerable under the glare of electric light. He looks tired, yes, but not only tired. He has an air of determination, too, as if he’s been laboring alone for hours, and years before that. There is no racquet in his hand, yet here he sits.

There has not been an openly gay man in the highest echelons of men’s tennis. Eventually there will be, and I imagine his experience will be much like the plight of this man alone on the clay. I imagine many intrusive electric lights directed brashly at his body. I imagine the years he’ll travel alone. Inevitably, he will have to work that little bit harder, that little bit later into the night, to earn the respect of his peers. Ultimately that respect will come based on his ability to win, and his capacity to lose.

Though it’s naive to think of tennis as a pure meritocracy, it is forehands and backhands that will, match by match, break open the closet doors for those who follow. In 2021 there are some who mistakenly believe the closet is passé, but it remains radical to be gay. It is still transgressive to step out in your truth.

Until such a day as those closet doors are busted open by some young rogue on tour, I’ll claim a small victory in the form of a painted figure sitting courageously alone. In the two-dimensional stud on his couch, swiping through similarly flat promises of companionship. In the chattering youths swarming a winner making her way through to another round.

I can think of nothing more perfectly, loudly Parisian than Claracq’s portrait of Roland-Garros after dark. It is a wonderful act of creation.

This Roland-Garros poster is radical. This Roland-Garros poster is gay.

Andrew Eccles is a writer, a digital content manager, and the creator of The Spin—a weekly tennis newsletter. Originally from Middlesbrough, U.K., he is now based in Brooklyn.