By Akash Kapur

I grew up playing tennis on red clay in the South Indian countryside. I was a child in Auroville, an intentional community located on a barren plateau some 100 miles south of Madras (now Chennai). The community was small, a mere 300 people or so, and life there was spartan: thatch huts, many without electricity or running water, all situated on a desert landscape that felt very cut off from the world, both geographically and psychologically.

Yet from its earliest days, the community had tennis courts: not one, but several, meticulously watered every day with hosepipes, their lines hand-painted with a concoction of white lime and water mixed in rusty metal buckets. It helped that the surrounding earth was naturally red, colored by iron oxide in the soil; at least the earth for the courts didn’t have to be imported. But still, it always struck me as odd that my community, otherwise so harsh and undeveloped, had something of a thriving tennis culture. What accounted for the apparent incongruity?

The answer, I later understood, had to do with a Frenchwoman named Blanche Rachel Mirra Alfassa. Born in Paris in 1878, Alfassa (known to everyone in Auroville as the Mother) moved to the nearby town of Pondicherry, at that time a French colony, in the early 20th century. In collaboration with the Indian mystic and former freedom fighter Aurobindo Ghose, she built an ashram, or spiritual retreat, that ultimately grew into one of the largest such settlements in India. Auroville, my hometown, was an offshoot of the ashram, an intentional project intended as a laboratory to manifest the teachings of Sri Aurobindo (as he was known) and the Mother.

The Mother was an accomplished spiritualist, but she was also a prodigious manager and builder in the physical world. Under her direction, the ashram developed several schools, a post office, farms, a paper factory, various handicraft units, and at least two sports grounds—one of which contained red clay and cement tennis courts, tucked into a corner alongside Pondicherry’s seaside promenade, overlooking the shimmering waters of the Bay of Bengal.

The Mother was an avid tennis player. She began as an 8-year-old in France and, after moving to India, played nearly every evening on the ashram tennis courts. Through her own enthusiasm, she cultivated a love for the game among members of the ashram. Children would head enthusiastically to the seaside to watch her play; many cultivated their hand-eye coordination by playing Ping-Pong (of which the Mother was also a skilled player). Adults gathered too. As the Mother’s renown spread, she began attracting a growing flock of followers. One of them would later describe her game in distinctly glowing terms: It was “as if she was playing with the whole universe,” he wrote, “every ball was as it were the universe and she was beating the universe as it were with her racket.”

Tennis, I’ve come to understand, runs in genealogies. My two sons, now teenagers and competitive players, acquired their game—and love for the game—because they grew up with a tennis father. I didn’t have tennis parents, but the reason I play is because I grew up in the Mother’s township. Her own love for the game, cultivated perhaps by a relative or friend when she was a child, was indirectly transmitted to me, through those incongruously manicured courts in my otherwise underdeveloped and spartan town.

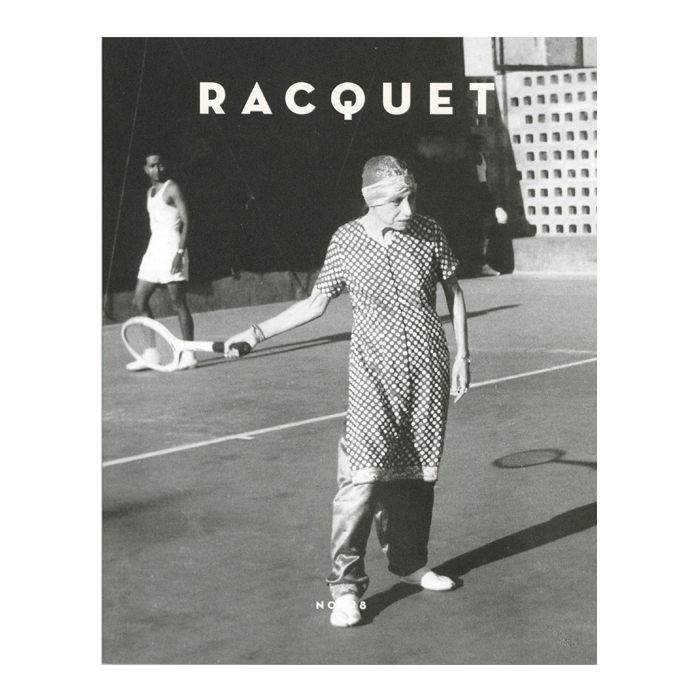

In 1950, the French photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson visited Pondicherry and took a series of portraits of Sri Aurobindo and the Mother. Many of these are highly posed, representing them in their role as spiritual leaders. But along with these more formal portraits, there exists a series of pictures of the Mother on her tennis courts; these photos are far more carefree, even fun. The Mother smiles; sometimes she plays on her own, swinging that cosmic forehand, while in other shots she’s accompanied by a muscled doubles partner dressed in white shorts and a skimpy undershirt. The Mother, by contrast, is covered in white from head to toe, with only her forearms and face revealed.

I’ve always loved these pictures of the Mother playing tennis—perhaps because they remind me of my tennis genealogy, but equally, I think, because of their lightness. Tennis is an intense, often psychologically painful, sport. I’ve always believed that a big part of the game’s challenge—and one of the keys to winning—is simply to have fun. This is something on which my coach, a Frenchman whose own father had worked with the French Davis Cup team, always insisted. “You’re too serious, Akash,” he would say. “You look miserable out there. Try to enjoy the game!”

When the Mother played tennis, she would smile. She would shed her austere demeanor, her eyes would soften, and her joy for the game would reveal itself in a big toothy grin. Her shoulders seemed to relax. Even a formidable spiritual leader needs a break. I think the Mother’s evening tennis offered her a respite from the daily burdens of administration and management that she carried at the ashram.

In 1958, at the age of 80, the Mother began suffering a series of health problems. She ceased playing until her death, in November of 1973. I was born nearly a year later. In the early ’90s, I moved to America to attend boarding school at Phillips Academy Andover, where I played varsity tennis. One day my coach, who doubled as a philosophy teacher, expressed some bemusement about my forehand, which he felt was uncommonly powerful. He knew a little about the unlikely setting where I had grown up, and he wanted to know how it was that I had acquired such a stroke. I can’t remember what I answered, but I know what I should have said. I should have told him that I owe my forehand—like the rest of my game—to the Mother.

Above: Photo by by Henri-Cartier Bresson

Akash Kapur is the author, most recently of Better to Have Gone: Love, Death, and the Quest for Utopia in Auroville. You should totally buy it.