By Giri Nathan

I often wonder how much players keep the actuarial stakes of a given match in mind while they’re still playing it, if the ranking points ever distract them from the actual tennis points. When Maria Sakkari won her semifinal match in Indian Wells this March, she knew immediately that she had become the No. 3 player in the world. “[In Greece] I was always the person and the player that, because my mom was very famous back home, they always used to say, ‘She’s never going to make it, even if she changes everything. She will never make it.’ And then suddenly, out of nowhere, I become one of the best players in the world,” she said at media day in Montreal last weekend. That No. 3 ranking is the high-water mark for any Greek tennis player ever, tied only by her pal Stefanos Tsitsipas. But the freedom of the underdog suits some people more than the pressure of the favorite; Sakkari learned that she was one of them. After losing in the second round at San Jose last week, she sat down with her coach, Tom Hill, and stared down reality.

“I just sat down with Tom for a lot of hours and just realized that I’m not enjoying being one of the best players in the world, which was something very tough to admit and very tough to handle,” said Sakkari. “But it’s the truth. It’s the reality. I think that the pressure and everything was something I had to deal with.” Since making that final at Indian Wells, Sakkari had gone 10–11. At Roland-Garros, where she’d blazed into the semifinal last season, she instead got bounced in the second round. At Wimbledon, she lost in the third round. Only once did she manage three consecutive wins. It was a cold summer for a player who should have all the heat. She doesn’t lack for tools: compact ground strokes, a serve that way outperforms her modest height, perhaps the most formidable fitness (and back muscles) in tennis, all tied together with an increasingly aggressive game plan. She also turned 27 last month, entering prime years for the contemporary tennis player. But it wasn’t cohering. “Sometimes when you are on the tour and you play week after week, you don’t stop and you don’t realize what you have really achieved. It takes time for some people, and I believe that it took time for me,” she said.

Ahead of Montreal, Sakkari believed she was returning to her normal self and promised the world that “you’re going to see a different Maria than in the last three months.” She enjoyed the first-round bye—perks of top-seeded life—and then took out Sloane Stephens in three sets. Her third-round matchup was the ever-dangerous but recently spotty Karolina Pliskova. The first set was very much not the Maria that was promised; Sakkari notched 13 unforced errors and 0 winners as she lost it 6–1. She went down an early break in set 2. But due to Pliskova’s sometimes baffling inability to close—one second serve flew 10 feet long on a match point—Sakkari bashed her way back into the match. In the direst moments one could even spot the glint of a smile on her face. In set 3, a handful of astonishing forehands kept Sakkari alive on match points, but eventually, with chance No. 6, Pliskova finished the job, 6–1, 6–7(11), 6–4.

As of late, the top of the WTA has seen constant churn. Depending on your taste in tennis fandom—sustained narrative-building or day-to-day surprises—this churn may either frustrate or delight you, leading you to either bemoan the lack of consistency or praise the depth of the game. I’m torn: As a pure fan, I’m all for chaos, but as a paid narrative-builder, I sweat a little harder at the keyboard. Few players have managed to reach the top of the mountain and stay there. Sakkari is now trying to figure out if she can cope with the newfound pressure and become one of them. She might just have to heed the recent advice of her mother, former world No. 43 Angeliki Kanellopoulou, which Maria summed up thusly: “Just try to enjoy this journey as much as you can. It doesn’t last long.”

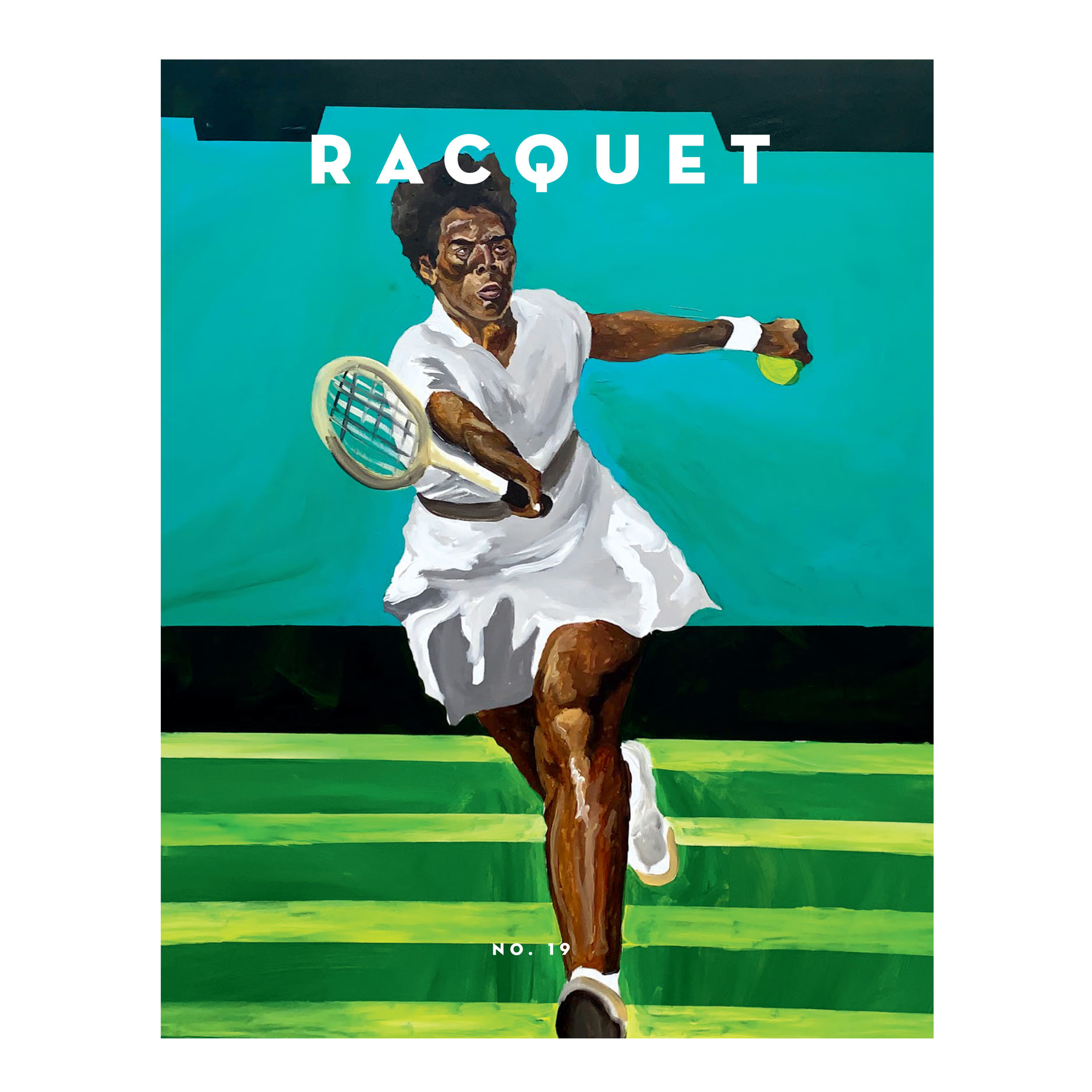

Above: Top 3 player, Top 3 outfit. (Alamy)