By Paul Glenshaw

The Name Roland Garros Is on the Lips of Tennis Fans Each May, but the Tournament's Namesake Was a Different Kind of Ace

Most stadium names have a clear logic—a city, a legendary player, or a sponsor. Think Wimbledon, Arthur Ashe, even the Hard Rock. But then there’s Roland-Garros in Paris, home of the French Open. The tale of the stadium’s namesake begins in the middle of the Indian Ocean and is tied up with a pair of rugby-playing schoolmates in Paris, the dawn of aviation, and the First World War. But ultimately, it’s about the admiration of one friend for another—and not really at all about tennis.

In 1927, Émile Lesieur, a onetime record-setting sprinter and star rugby player, decided to keep the once-famous name of his late friend Roland Garros alive. Garros had been internationally renowned as a pioneer pilot before WWI and then became a war hero, giving his life for France. Garros had been dead nearly 10 years when Lesieur found himself with a unique opportunity to memorialize his comrade. He partially succeeded. Anyone who knows tennis knows the name Roland Garros, but very few have known his story.

***

Roland Garros was born on Oct. 6, 1888, far from Paris on the tiny French colonial island of Réunion in the Indian Ocean, east of Madagascar. His father, Georges, was an ambitious lawyer who soon moved his family to Saigon, in the French colony of Indochina, when Garros was 4. Garros grew up somewhat isolated from well-heeled French colonials, making friends with the Vietnamese and Chinese children in his neighborhood. He also discovered the bicycle—and with it, his first taste of speed and independence.

His domineering father enrolled Roland in an elite Parisian boarding school—without consulting his mother. Only 11 years old, Garros was put on a ship to France alone. Garros remembered crying tears of rage at his father and tears of sadness for his mother. After arriving in Paris, he was diagnosed with pneumonia and was sent to another campus, on the Côte d’Azur. His health recovered quickly, and Garros found his tribe—in sports. He vigorously competed in track, soccer, and especially bicycle racing. During summertime visits to family friends’ homes in England, he began playing tennis—but only ever for fun.

Although his family returned briefly to France from 1901 to 1903, Garros essentially raised himself. In 1906, at age 18, he enrolled in the École des hautes études commerciales de Paris (a business school commonly known as HEC). He soon met classmate Émile Lesieur, and they became fast friends. Lesieur had already established himself as a star athlete, far in advance of Garros.

The year 1906 was huge for Lesieur. He won the 100- and 400-meter races at the Championnats de France d’athlétisme. Playing for the rugby team Stade France, he scored the first-ever French try against a British team, during a match that the British won by 27 points (France had some catching up to do in rugby). Lesieur encouraged Garros to try rugby, and Garros landed a place on the Stade France reserve team. Garros and Lesieur were at the center of a close group of friends playing, studying, and socializing together. They graduated HEC in 1908 and remained close, Lesieur continuing in rugby as a leader of the Stade France team, and Garros with his quest for speed—now with a commercial twist.

Garros landed his first job, working the Grégoire Automobiles booth at the 1908 Paris auto salon. With encouragement from Lesieur, he soon found himself as the proprietor of a Grégoire dealership on the Champs-Elysées. Cars were more glamorous and faster by far than bicycles. Now in their early 20s, he and Lesieur and their friends indulged in the pleasures of belle epoque Paris. But something happened in the summer of 1908 that would change the world, and Garros’ life, forever: Wilbur Wright made his first public flights at Le Mans.

The Wright brothers made their first successful flights in 1903 and were able to fly almost 40 kilometers by 1905, but all out of the public eye. Others began to struggle into the air, especially in France, where flight had been an obsession since the 18th-century balloon flights of the Montgolfier brothers. In Paris, Alberto Santos-Dumont made his first straight-line hops in 1906. Henri Farman made it around a one-kilometer circuit in 1908. But no one had really seen how far the Wright brothers had advanced. With a sales contract in hand from a French business group, Wilbur Wright came to Le Mans, took off, and blew everyone’s minds. He had complete control—sweeping turns, figure eights—all deftly performed. The aviation genie was out of the bottle; human flight had indeed been achieved.

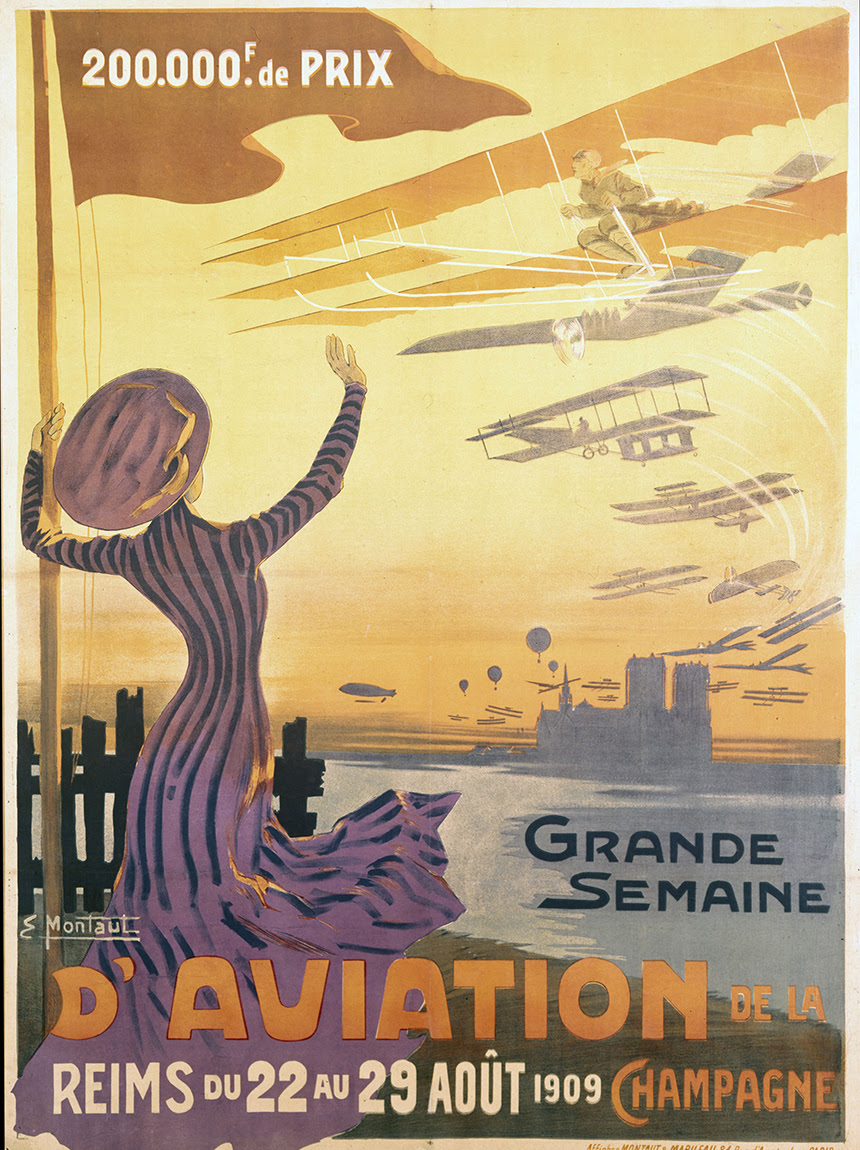

Garros’ introduction to flight was at Reims in August 1909 when he attended the first true air show—La Grande Semaine d’Aviation de la Champagne. Much had happened since Wilbur’s debut, especially Louis Blériot flying across the English Channel. Almost two dozen aircraft flew at the meet—the greatest concentration of airplanes to date. The highlight was the Gordon Bennett Cup race, which was won by an American speed freak named Glenn Curtiss, with the astonishing speed of 47 miles per hour.

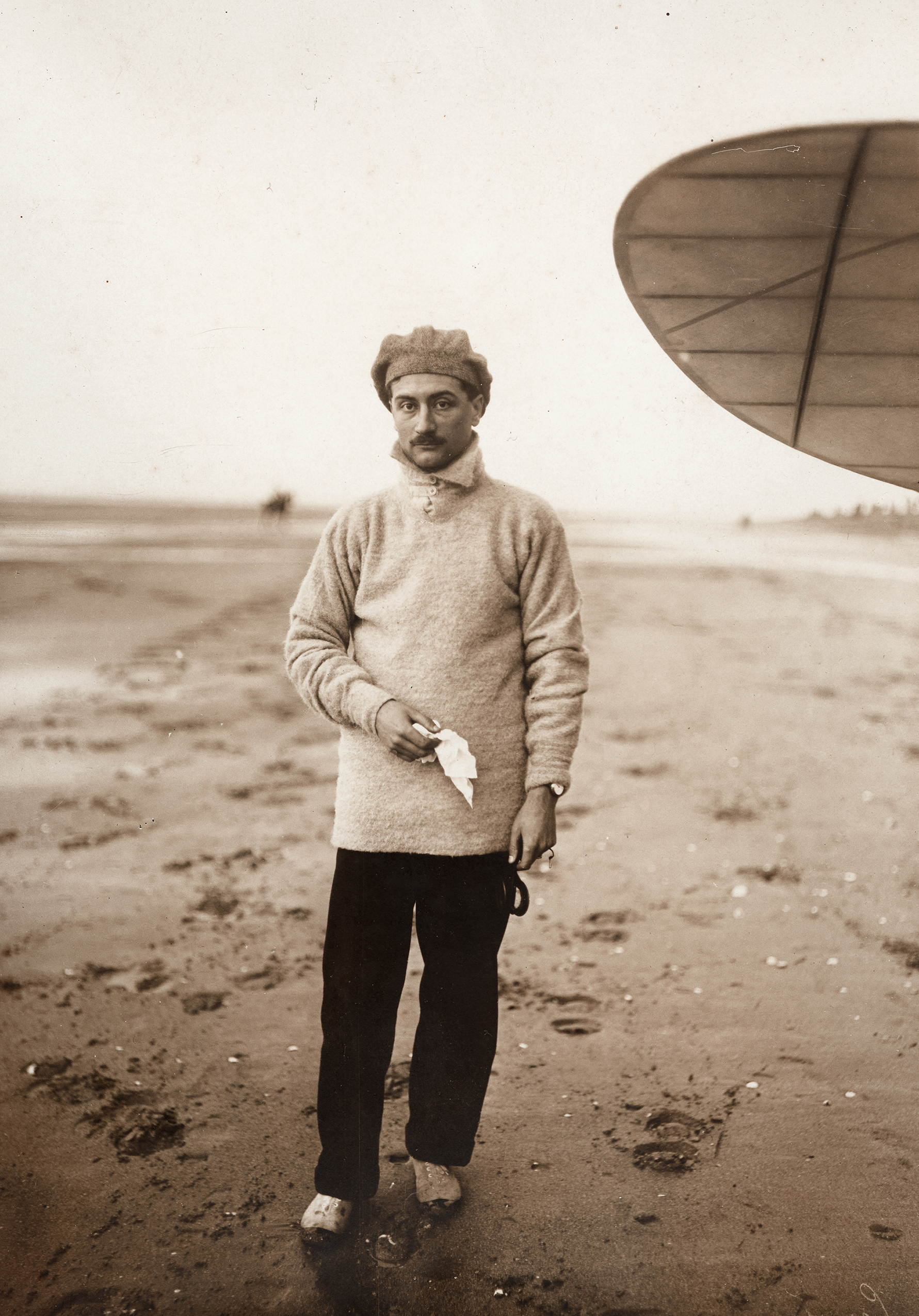

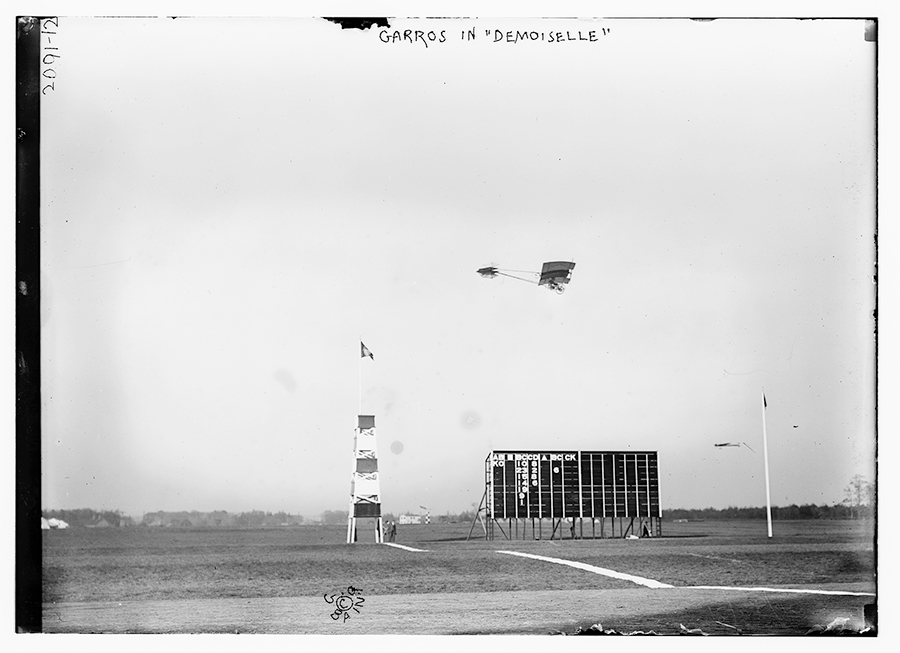

Utterly captivated, Garros turned all of his attention to aviation. He purchased a Demoiselle for 7,500 francs in April 1910. By today’s standards, it was a shockingly frail aircraft made of fabric and lashed-together pieces of bamboo. The first pioneers, like the Wrights, Curtiss, Santos-Dumont, and Blériot, all taught themselves to fly and began opening flight schools. But some fledgling aviators simply bought their airplanes and figured it out for themselves. Garros was one of these lucky few.

Indeed, on his very first attempt to fly the Demoiselle, luck kept Garros alive. While taxiing down a grass strip, he noticed too late that he was directly in the path of another, much larger biplane coming in to land. Garros’ tiny machine was completely destroyed, but he was unhurt. Even more, the pilot of the biplane felt responsible for the crash and bought Garros a new Demoiselle.

***

Garros soon received his license (#147) and—as most pioneer aviators did—launched a new career as an exhibition pilot. Early airplanes really couldn’t do more than demonstrate that flying was possible. And the thrill-seeking public knew that dashing aviators often met dashing ends, and they’d pay for the chance to see either. Garros began performing in aviation meets and competing in races for glory and cash. He flew demonstrations at Cholet and Rennes. He flew over Versailles. In the fall of 1910, he gained a place on the French team of aviators competing at the Belmont racetrack outside New York City. Lesieur went to the train station to see him off. Garros’ American adventure was underway.

Garros’ showing at Belmont in his underpowered, hopelessly outclassed Demoiselle was dismal. But his teammate, a Canadian-American named John Moisant, flew a more powerful Blériot monoplane and performed well, capturing first place in a race to the Statue of Liberty and back (although he was later disqualified for starting late). When the meet ended, Moisant hired Garros and the other members of the team to form the Moisant Flying Circus, and they set out across the American South. Garros graduated to the Blériot and performed in Richmond, Chattanooga, Memphis, and Tupelo. Moisant was killed on New Year’s Eve in New Orleans, but the rest pressed on to Texas, Oklahoma, Mexico, and Cuba. When he returned to France in early 1911, Garros was a seasoned and increasingly famous exhibition pilot.

Over the next three years, Garros became one of the preeminent names in aviation. He competed in the Paris–Madrid and Paris–Rome races, toured Brazil, and set altitude records of 12,960 feet (1911) and 18,410 feet (1912). The aircraft he flew were of higher and higher performance. His crowning achievement came on Sept. 23, 1913, when he took off from Fréjus-Saint Raphaël on the southern French coast and landed eight hours later in Bizerte, Tunisia, becoming the first person to fly an airplane over the Mediterranean Sea.

***

Garros was guaranteed enshrinement in aviation history as one of the true pioneers for demonstrating the potential to travel great distances by air. But after Germany declared war on France and England in the entangled mess of alliances that led to WWI, Garros enlisted and was assigned to Escadrille MS23. He became a pioneer again—by making the airplane a lethal weapon of war.

The most important use of the airplane on both sides was the taking of aerial photographs of enemy troop and artillery placements and movements. Shooting down reconnaissance aircraft became a priority. The need for the fighter pilot was born.

But there were no fighter pilots at the beginning of the war, nor any specialized weapons for shooting down enemy aircraft. Handheld guns were used at first, but with the machine gun going into widespread (and catastrophic) use on the ground, efforts to use it in the air began quickly. At first, machine guns were mounted on the aircraft at a 45-degree angle to the side—very difficult to aim. Roland Garros had the breakthrough.

“He’s the first one to realize that the ability to successfully attack another airplane in this space, with an automatic weapon, is predicated on aiming the airplane and the weapon at the same time in the same direction,” says WWI aviation historian and pilot Mike O’Neal.

Garros’ innovation was based on a simple idea: simply protect the propeller from the bullets. He and his mechanic fashioned steel wedges that were mounted on the back of the propeller exactly where the softer lead bullets would hit and deflect the bullets harmlessly away. “Regardless of how crude this may be, [that] he’s gonna shoot into these wedges on the back of his propeller,” says O’Neal, “the brilliance here is making that connection between the line of flight and the line of fire.”

On April 1, 1915, Garros tried his invention with success, shooting down a German Albatros observation plane. In the following weeks, two more kills quickly followed. Word spread quickly among allies and enemies. Garros became a new kind of war hero—a true fighter pilot—as well as a wanted man. His frontline glory was over quickly. He was shot down on April 18 and crash-landed his wounded plane behind the German lines. Garros tried but failed to burn his machine to protect its secret weapon before he was captured. The Germans had two prizes: Garros was sent to a prison camp, and his airplane was sent to the preeminent designer of German fighter aircraft, Anthony Fokker.

(Fokker improved Garros’ concept by developing a mechanism that interrupted the firing gun when the blade passed in front of the barrel. This innovation was adapted by both sides and dominated fighter planes for the rest of the war.)

Garros languished in prison for three years, finally escaping in February 1918. After a brief respite in Paris, he returned to the front with Escadrille 23. Everything had changed. Garros was older and had not flown in three years. “The aircraft technology has changed to such a huge extent. It’s become faster, they’re more maneuverable, they operate at higher altitudes, they’re more physically demanding,” says O’Neal. Garros didn’t last long. He was shot down and killed on Oct. 5, 1918—one day shy of his 30th birthday and barely a month before the end of the war.

***

Fast-forward to July 1927. Aviation and tennis had been dominating the headlines. In early May, France’s second-highest-scoring ace of WWI, Charles Nungesser, disappeared over the Atlantic trying to win the prize for the first nonstop flight between New York and Paris. Two weeks later, young Charles Lindbergh landed in Paris and became a worldwide sensation. Garros’ accomplishments in the air paled in comparison—flight was looking forward, not back.

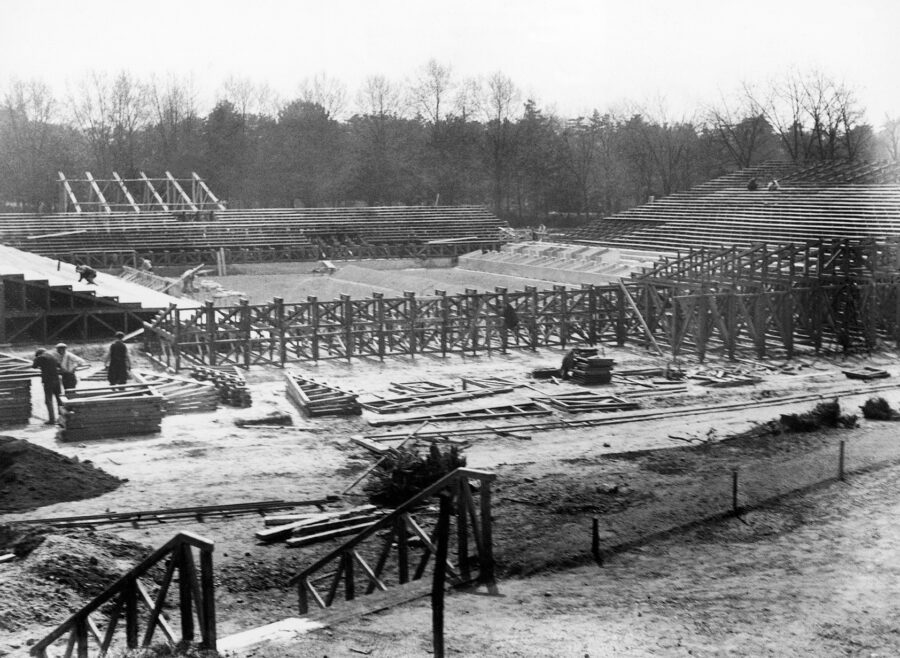

In tennis, France brought home the Davis Cup from the U.S. with the legendary Four Musketeers: Jean Borotra, Jacques Brugnon, Henri Cochet, and René Lacoste. Since France was to host the tournament in 1928, a new stadium had to be built in Paris. Reenter Émile Lesieur, Garros’ old friend from business school, rugby, and nights out in Paris. He’d become president of the Stade France rugby team. He and Pierre Gillou, the captain of the French Davis Cup Team, were charged with building the stadium in just nine months. Lesieur and Gillou had significant funding to raise and guaranteed their own property in the effort. Lesieur had one demand in return: that the new stadium be named for his heroic classmate, teammate, and friend Roland Garros.

Lesieur lived until just shy of his 100th birthday. Over time, the name Roland Garros became attached to the stadium and the French Open, and somewhat detached from the man Lesieur so admired. But things will be different now. Fans entering the stadium pass through Aviator Square, and by a six-meter-high sculpture of Garros by artist Caroline Brisset installed in 2021 and called The Cloud Kisser. Lesieur’s bon ami will be seen by thousands every year.

* It is possible that Lesieur also served as a fighter pilot in WWI. He mentions it—and being captured and escaping—in an interview from 1980, when he was 96. However, while Lesieur’s service is mentioned in other articles and books about Garros, it could not be corroborated in the online French military records for this article.

Paul Glenshaw is co-director, writer, and producer of the World War I documentary The Lafayette Escadrille. His work for the Smithsonian Associates includes his online series Art + History and Jazz in Paris. He was a longtime contributor and editor for Air & Space Smithsonian magazine, with expertise in the Wright brothers and pre-WWI aviation.