By Giri Nathan

There are fresh-faced tennis stars flourishing all over both tours. Over here, the 19-year-old Coco Gauff is carrying U.S. Open momentum to extend her win streak to 15; over there, the 22-year-old Jannik Sinner has reasserted himself by beating Carlos Alcaraz and Daniil Medvedev to title in Beijing. And over there, the 23-year-old Sebastian Korda is…losing an ATP final to the 35-year-old journeyman Adrian Mannarino, the man with the peculiar ping-pong strokes, who is having the season of his life at a rather advanced age. As with Agassi, baldness seems to have brought Mannarino tennis enlightenment. So forget the kids for now—today I want to dwell on this technically anomalous, frequently irritable Frenchman, winner of the Astana 250 event and unlikely fount of the most absurd highlights you’ll ever see.

“He’s so annoying to play,” Frances Tiafoe said after beating Mannarino in their third-round U.S. Open match last month. “He’s just bunting the ball around, it’s so slow. You look at him and you’re like, ‘Man, what’s he doing?’” It’s true. What’s he doing? At a glance, Mannarino seems to be playing a different sport from his peers. Whether it’s Tiafoe doing his wildly loopy forehand, Rafa executing his classic buggy-whip, or Carlitos hurling himself into the air to smack the felt off the ball, they’re all powerful athletes recruiting all the muscles in their body to hit the tennis ball as heavily as possible. And then there is Mannarino, who does everything small. Just watch how he beat Korda. He barely cocks his racquet back, then takes these abbreviated baby bunts, like the swings you might mime with the palm of your hand while walking around your living room. They look suitable for a ping-pong ball. They don’t look like they should be able to transport an object as heavy as a tennis ball over distances as long as a tennis court. An off-balance flick, a casual love-tap, but it always puts the ball in inconvenient places. Then he scurries around the court and does it again. The result is deadlier than you’d suspect, and there’s more to Tiafoe’s quote: “But it’s so effective, the ball stays so low. He makes you create, he makes you feel like you want to overplay.”

This idiosyncratic style was, in part, the product of abrupt and inexplicable wrist pain that interrupted Mannarino’s career in 2011. The lefty found himself unable to hit his usual forehand, never found a satisfying medical solution, and was left with an unappetizing choice: retire or fundamentally change the way he played tennis. So he reworked his technique. All of his best results have followed that decision. His brand of tiny tennis is made possible by his equipment. Mannarino is famous for stringing his racquets at some of the lowest tensions on tour. Amateurs like you or I might string at 50 lbs; ATP preferences are all over the map but tend to cluster around the 50s and 40s, dipping into the 30s on occasion. Mannarino reportedly had his sticks strung at a hilarious 19 lbs for the Delray Open earlier this year. Tension that low turns the string bed into a trampoline, granting him easy power from baby swings. This combo of gear and technique is easy on the body, and he has the rare timing to pull it off, taking every ball early and placing it with care.

All this oddball technical stuff makes for a unique, almost darkly comic watch. There are long passages of precision pushing, and as Tiafoe suggested, those have got to be infuriating to play through as an opponent. But then, without warning, Mannarino will also attempt the boldest trick shot you’ve seen in months. He boasted the flashiest highlight of this past U.S. Open: a leaping, mid-air tweener on a ball he appeared to have overran. And he has sneakily been doing this hotdog stuff throughout his whole career. They’re like hidden Easter eggs for the true pushing enthusiasts out there. After this Astana title, Mannarino is ranked No. 23 in the world, just a spot behind his career high, and his 37 wins this year are already the highest tally of any season he’s had. Stay weird, Adrian.

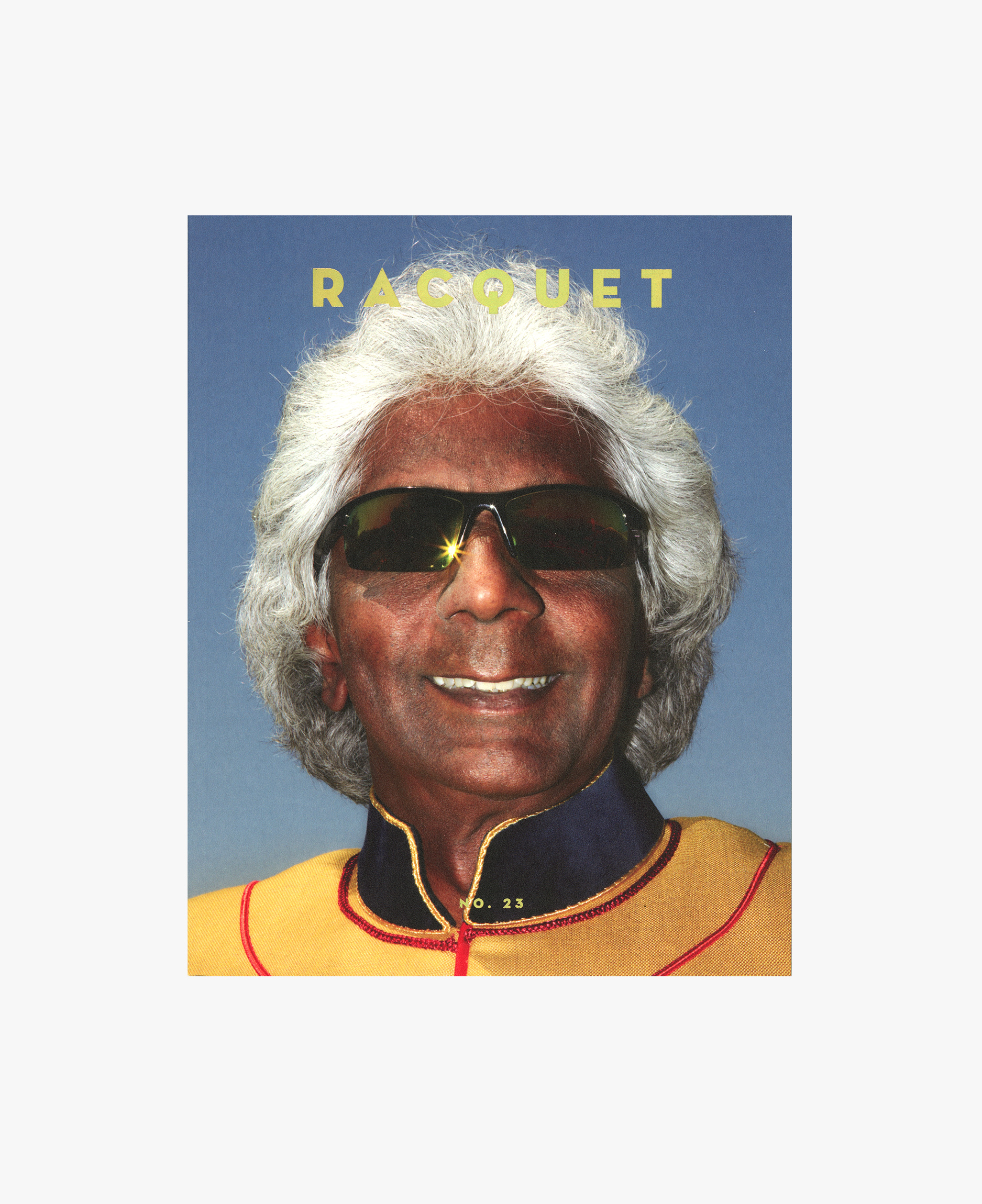

Above: Stay weird, Adrian Mannarino. (Getty)