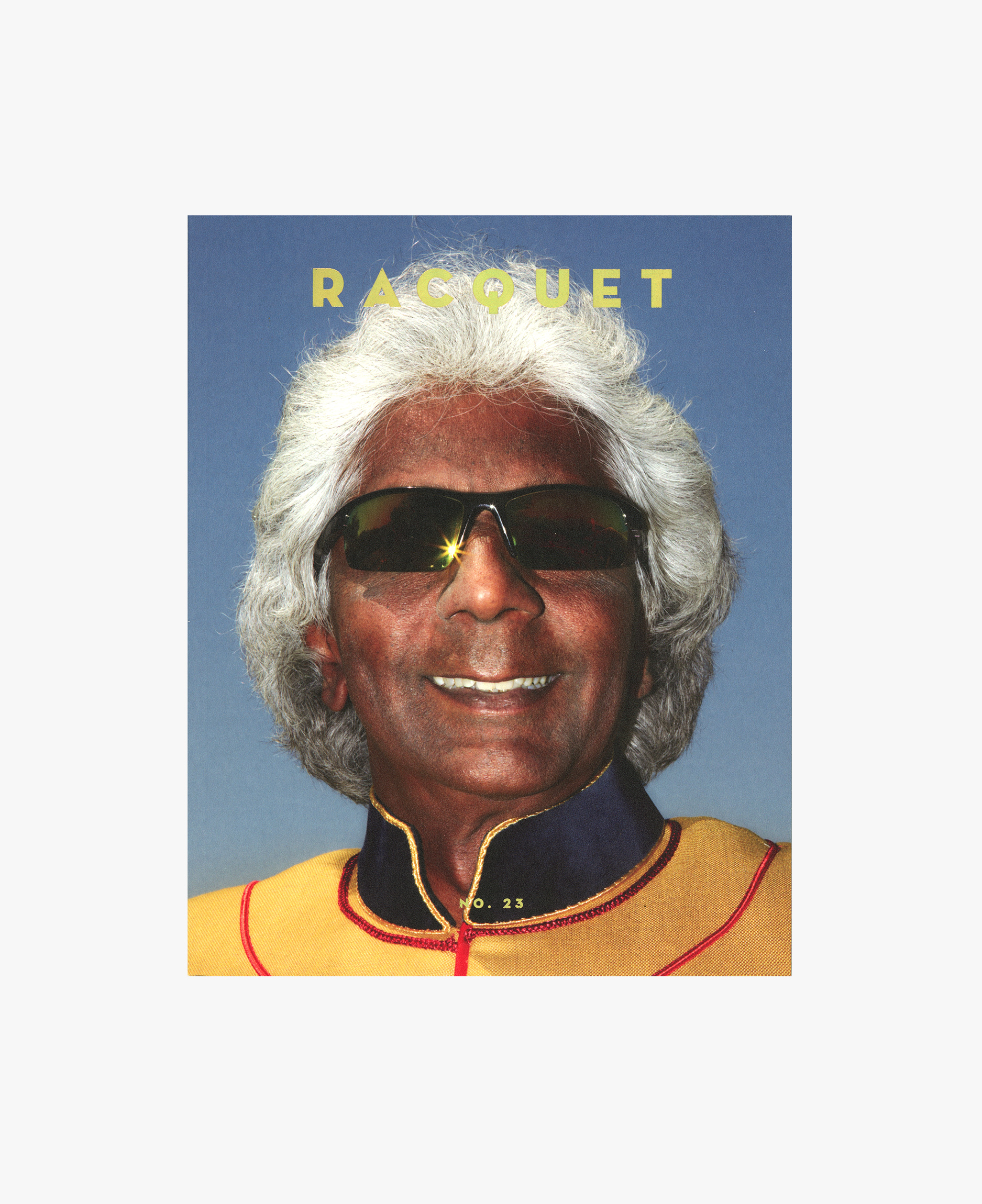

By Arun Janardhan

Photographs by Akshay Kolse-Patil

The Baseline Became the Front Line in This Crucial World War II Battle.

Writer and historian Dr. Robert Lyman, whose book A War of Empires: Japan, India, Burma & Britain: 1941–45 documents Japan’s first defeat in World War II, refers to the battles of Kohima and Imphal as “a modern Thermopylae.” Referring to the famous Spartan standoff against the Persians, Lyman compares how a small number of brave men (about 1,500 Indians and British) fought against overwhelming numbers (about 15,000–20,000 Japanese) in remote northeast India.

The Battle of Kohima—or the Battle of the Tennis Court, as it has come to be known—was a significant event in the Second World War but does not often find a place in the larger discourse on the subject. The core of the battle was concentrated on a tennis court, built for the leisure of the British deputy commissioner, whose bungalow was nearby. The court provided the ideal flat land in what is an otherwise hilly terrain, then quite densely forested.

“Strategically, one of the things that neither London nor Washington had ever believed would be possible,” writes Lyman, “all came about because of Kohima, because of this remarkable tennis court. It’s one of the most extraordinary battles in human history.”

Fought in the extreme northeastern region of India that bordered the country then known as Burma, Kohima was far from the more well-known theaters of WWII. Crucial though it was, the battle has been reduced to a footnote, of interest mainly just to military historians and travelers who happen upon the monument that today still delineates the deputy commissioner’s tennis court. Shortly after the war, a newly independent India widely came to view this type of history as part of its British colonial past and therefore not worthy of engagement[DS1] .

“Even in the U.K., the [British] Fourteenth Army was known as the forgotten army, because everything was so Eurocentric. Not much attention was given to Kohima,” says retired squadron leader, historian, and writer Rana T.S. Chhina.

***

The battleground of Garrison Hill lies at the center of the city of Kohima in the state of Nagaland today. A war memorial and cemetery stand here. White concrete lines mark the tennis court, which has a big cross atop a pedestal in the middle. Visitors entering the memorial have to climb up the hill upon entering through the main gates. This ends at a wall that has the names of all 917 Hindu and Sikh soldiers who died in battle and were cremated.

The cemetery has 1,420 Commonwealth burials of the Second World War, according to the Commonwealth War Graves Commission. Near the entrance is a memorial to the 2nd Division with the inscription: “When you go home, tell them of us and say, for your tomorrow, we gave our today.”

Utpal Borpujari’s 2016 documentary film, Memories of a Forgotten War, also shows a plaque bearing the sign: “This flowering tree is of historical interest. The original tree was used as a snipers’ post by the Japanese and was destroyed in the fighting which raged around the tennis court and marked the limit of the Japanese advance into India. The present tree is a shoot.”

Borpujari says, “My idea of making this film was to tell stories from the region [northeast India] that’s not known elsewhere. I wanted to tell the story from a human point of view.”

For the film, he interviewed British, Japanese, and Indian soldiers and local residents who fought in or experienced the battle, some of them over 90 years old. Shot mostly in 2014 during the 70th-anniversary remembrances of the battle, the film took another two years to complete.

“There are unused mortars and unexploded grenades found in the Nagaland fields even today. Many, including children, have been maimed and killed because of them,” the journalist-turned-filmmaker says.

***

Japanese troops first arrived in Kohima on 4 April 1944 with the 31st Japanese Division under Lieut. Gen. Kotoku Sato.At about 5,500 feet above the Brahmaputra River, in the hills that separate the state of Assam from Manipur, Kohima’s geographical location was not of any strategic importance. About 45 miles to its northwest is Dimapur, then the logistic nodal point for all Allied operations, a railhead and link for coal, oil, timber, and tea. Around 85 miles southwest is Imphal, the capital of Manipur.

“In the Japanese plans to secure Imphal, they recognized it was important to close the road into the Brahmaputra Valley,” Lyman says. “If Kohima was closed or blocked, the British couldn’t then reinforce. Kohima was an accidental battle, really. It was not the place where it should have been fought.”

The road from Imphal to Kohima loops around a ridge, where the main battle was fought. The first part of the battle that involved the tennis court was waged from 4 April for under two and a half weeks. On top of that ridge in 1944, called Summer House Hill, was the British deputy commissioner’s bungalow, which was destroyed in the fighting. A track went up some bougainvillea groves just above the bungalow leading to the tennis court, which became the focal point of the fighting.

The fight was brutal, World War I-style trench to trench, bayonet to bayonet, with the troops in hand-grenade-throwing distance of each other, according to Lyman, who is a research fellow at the Changing Character of War Centre, Pembroke College, University of Oxford. “There was a period of time when the Japanese were firmly entrenched in the southern and northern part of the ridge, with the British and Indian soldiers stuck in the middle around the tennis court. The tennis court was contested ground.”

Japan’s surprising defeat has been attributed to the idea that the Japanese had underestimated the British and Indian forces, which had been rebuilt between 1942 and 1944. Over 80 percent of the British Fourteenth Army were Indian soldiers. It didn’t help that in 1944, the monsoon came early, which caused the invading soldiers many maladies, including illnesses like malaria and dysentery.

“The bulk of fighting was by Indians,” says Chhina. “During WWII, the Indian army had risen to a strength of 2.5 million men. They were all volunteers, the largest volunteer force in history of human conflict. Without active help of Indian army, the whole course of WWII would have been different.”

On 25 May 1944, Lieutenant General Sato asked Lt. Gen. Renya Mutaguchi for permission to withdraw but was refused. On 31 May, Sato ordered his troops—exhausted, ailing, and short on supplies—to withdraw from Kohima. By 22 June, the siege of Imphal had ended.

“Mutaguchi was ordered to fight, but he had no supplies,” says Chhina, who has written India and the First World War 1914–18 and Battle Tales: Soldiers’ Recollections of the 1971 War, among other books. “Mutaguchi disobeyed his commander—the first time in Japanese military history that it happened.”

“It was one of the turning points in the Second World War,” adds Lyman, “like Stalingrad, like Midway, where the Japanese reached the high point of their military ambitions and returned. A thousand Indians with 500 Brits fighting together unexpectedly defended Kohima by their brilliance and perseverance.”

Arun janardhan is a Mumbai-based sports and feature writer. He can be found @iArunJ.

Akshay Kolse-Patil is a Mumbai-based lawyer.