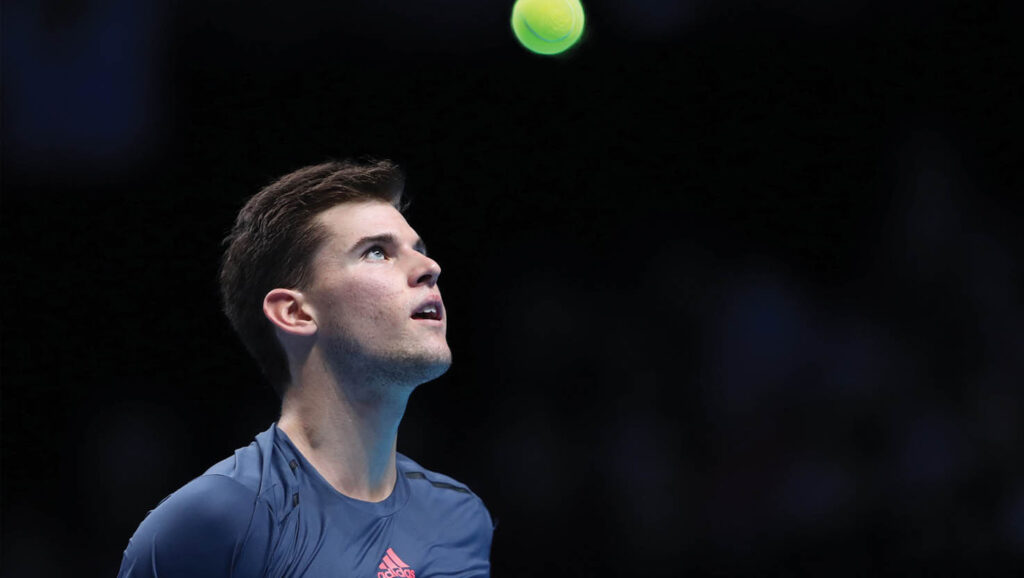

In August, I watched Dominic Thiem play the last Grand Slam match of his career, courtside in Arthur Ashe stadium. Thiem’s family and team were in his box, including former coach Nicolás Massú, their faces solemn in the midday sun. American Ben Shelton, whose star power and biceps have only increased in size since his breakout season last year, was Thiem’s opponent. Thiem played with occasional moments of beauty—the ghost of his US Open-winning self dancing in the shadows of a one-handed winner—but Shelton devoured him. It was heartbreaking, and perversely compelling.

I don’t know what it says about me, but exploration into this kind of pain has long fascinated me. The body and the mind shutting down are within the natural order of things, but it’s always melancholic when it arrives in surprise order—Ashe was, after all, the site of Thiem’s greatest victory four years prior. Watching him at this year’s Open was to see the other side of a dream halted cold. I wrote for Racquet Issue 25 about Thiem’s journey—the vaunted heights he climbed to, and the unwavering agony of the fall. -Caira Conner

The following is excerpted from Caira Conner’s “Dominic Thiem’s Crucible of Pain” in Racquet Issue 25.

All professional tennis players dream big, and work hard, but rarely do those golden aspirations amount to actual conquest and fortune. But Domi Thiem was one of the chosen. At the 2017 Italian Open in Rome, 23-year-old Thiem beat still-in-his-prime Rafael Nadal on clay, and in short order sent Novak Djokovic careening out of the French Open a few weeks later in the quarterfinal, in straight sets. He lost the Roland Garros semi to Nadal, but made a good showing at Wimbledon and the US Open, exiting both in the fourth round. That fall, GQ called him the future of tennis; by the end of the 2017 season, after years of starts and skidded runways, he was the world No. 4.

April 19, 2018, and it’s Thiem and Djokovic in the fourth round on the slow-clay courts of Monte Carlo. Thiem knocks him out in three sets. At the French Open final in June, Thiem loses again in straights to Nadal, but the crowd is enraptured by the presence of the clay king’s heir-apparent. The following spring, he wallops Roger Federer in the Indian Wells final to claim his first Masters 1000 title. He and Nadal meet again in the final of the 2019 French Open; Thiem loses, but this time he takes a set. Come year’s end, he’s collected 16 titles in total, five in 2019 alone. Along his way to the 2020 Australian Open final against Djokovic, Thiem beats Nadal in the quarters. Djokovic wins the Melbourne title, but by now, Thiem’s third appearance in a Grand Slam final feels like proof of life for players not named Roger, or Rafael, or Novak. The Big 3 are still here, still winning, but Thiem, with his beautiful backhand and frosted tips, is a force to be reckoned with, too.

He entered that year’s US Open seeded second.

Exit off the 7 train at Mets-Willet Point Station in Flushing Meadows, and the subway opens out onto a rare New York expanse. The crowds move in two directions, snaking back and forth along a boardwalk to and from the grounds entrance of the US Open tournament, the visors and the sunscreen and the scalpers moving through a thumping swell of enthusiasm. It’s always late summer, about to turn early fall, and the potentiality of tennis is thick. Each of the four grand slams has a distinct flavor; the sights and smells that shade its particular hue. Here, it’s dusk in September. It’s $22 Honey Deuce cocktails and bleachers for full-throated screaming.

One can imagine that for a player who makes the final––Arthur Ashe at last, after two weeks of day sessions and evening-turned-midnight sessions and time violations and upsets and injuries––the feeling is unparalleled. Thiem’s version, the one he wins six months after the world shut down for a global pandemic, is empty. Apart from Djokovic, nearly every other major contender for the title opts out of competing. There are no spectators. Press is virtual. The line judges wear masks. Djokovic gets disqualified in the fourth round, after a ball he hit purposefully in anger accidentally strikes a line judge in the throat. Thiem arrives at the championship match against Zverev ebullient in his Adidas hot-pink kit and a light goatee. It is still a grand slam final, after all, with a $3 million paycheck on the line.

It is still the pinnacle of everything he’s spent two decades working towards, the Everest that will make every sacrifice, ounce of suffering, and setback he stumbled through to get here feel like it had some larger cosmic purpose. Zverev moves through him quickly in the first set, nerve-free and with a deftly deployed serve-and-volley approach. Thiem’s effort is audible with every heavy grunt. He double-faults twice. One second serve sails feebly over the net at 68 mph. He is being outplayed. Zverev takes five set points to grind out a second set win. The match looks over. And then, just as unexpectedly as clouds part, the course changes. Thiem is awake. What unfurls over the next two-and-a-half endless hours is Thiem’s vindication. He returns from two sets and one break down in the third to overcome Zverev for the title.

Nothing about the win comes easily. The points are long, and girthy, and the stuff that would normally be drowned out by roars from the crowd––a plane overhead, the stomping echo of footwork––is heard through the television. There are no overstimulated fans to scream Thiem’s name. He never pumps his fist. The boy who suffered patiently with his backhand and then his height is forced by time and circumstance to win his slam to deafening silence.

The 2024 US Open looms. The site of his silent triumph. He does not speak publicly on the cost of what was taken: the French Opens he might have won after Nadal retired; the wrist he could have played with; the rivalries he should have had. His is the mythos of the comeback that wasn’t––the story of ungodly talent and tenacity and riches and success transmuted, in the end, into something quieter, fleeting, human. And still, gracefully, in his farewell disclosure, he cites an “inner feeling” as the guiding force behind his decision. Pain is the perennial victor, and it has won again.