By Giri Nathan

Tennis players hail from all over the world, congregate in one place, and move sweatily through shared locker rooms, past dozens of support staff, before traveling to some new far-off place and doing it all over again the next week. It’s practically tailor-made to contribute to the spread of a pandemic.

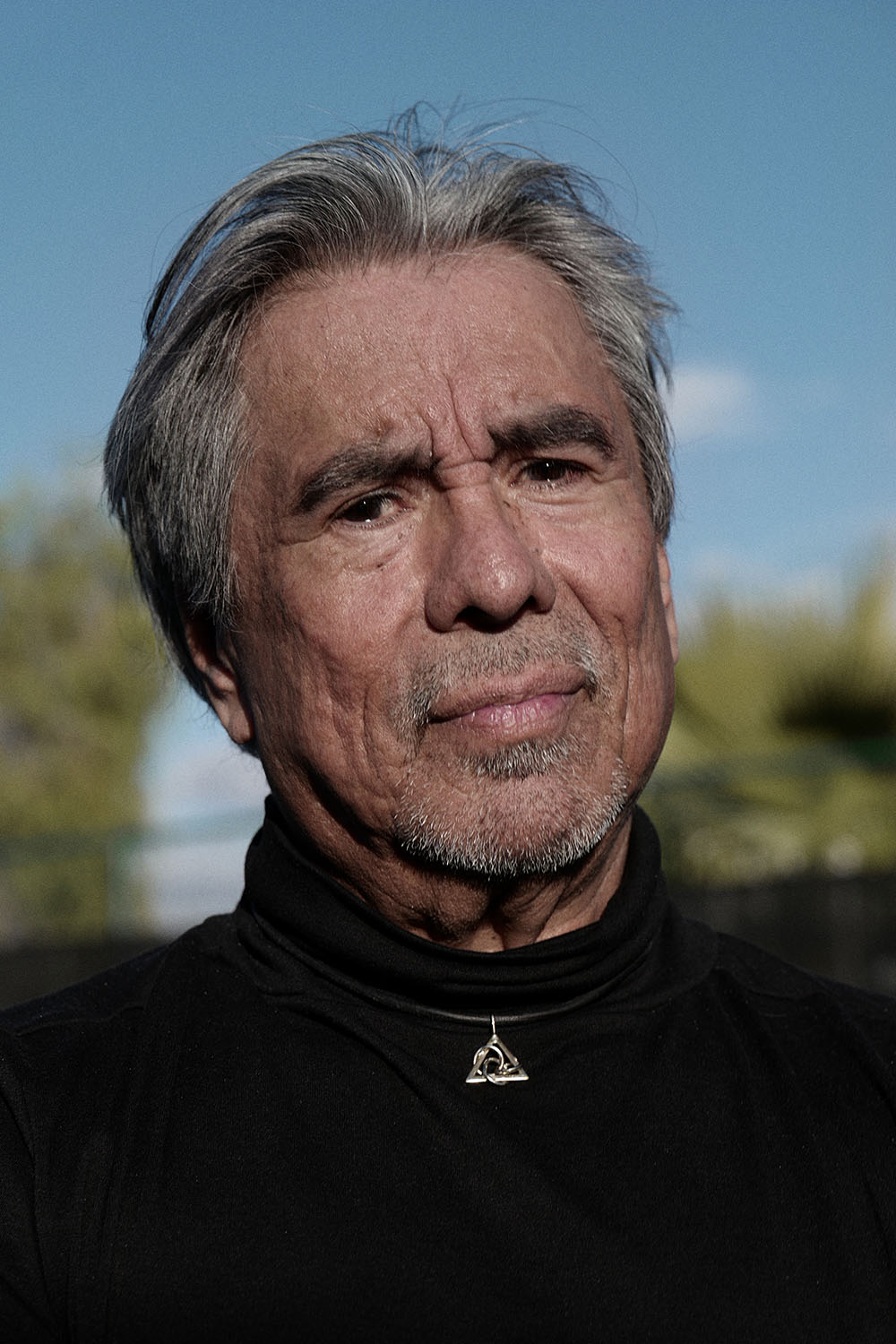

So perhaps it is unsurprising that the threat of COVID-19 has shut down the ATP Tour for the next six weeks at least; the WTA has cleared the slate as far as Charleston. We hope that you and yours are all staying healthy. Since there’s no tennis for the foreseeable future, it’s a good time to turn back to tennis from the past, as documented in our brand-new issue No. 13. Inside you’ll find my interview with Gil Reyes: trainer–slash–father figure to Andre Agassi, remarkable autodidact, strength and conditioning coach of some legendary UNLV basketball teams, Vegas legend, and all-around mensch. These days he trains athletes across all sports, including tennis’ own Eugenie Bouchard. We dug up some classic Gil-Andre stories, with cameos as diverse as Boris Becker, Frank Sinatra, and Larry Johnson. To whet your appetite, here are a few bits that we couldn’t fit in the issue.

GIRI:

You were transitioning from basketball to tennis, which was starting to look a little bit more like basketball—that explosive athleticism was starting to move into the sport. What was that transition like for you?

GIL:

Me having certainly no exposure to tennis, I found myself in this position and was able to kind of identify in Andre; he had that disposition, that instinct, that state of mind as a physical guy. He was talented, but he would tell me—and keep in mind, he was a teenager—he would tell me, “The sport is changing. The guys are getting bigger now, they hit harder. I don’t have the same time to return serve, or even get into the rallies and the ground strokes that I had before.“ Andre was one of the first big hitters in the sport as well. And he’d very simply just look at me, and he would say, “You know, the harder I hit the ball, the less time I have to get back in position.” And I’d just look at him and say, “Of course.” I would never have any way of knowing that, understanding that. So he took the role on as my teacher very, very efficiently and very graciously because he understood that I understood nothing about his sport. He would simplify it for me, saying, “I need to hit hard.” He says, “I’m a really good ball-striker, I need to hit the ball hard. But the harder I hit it, the less time I have to get back in position.” So he would tell me, not just running, but what type of running, not just movement, but what type of movement, not just quickness, but what type of quickness he needed to enhance his performance on the court.

GIRI:

You were coming into tennis without a huge background in it. Was there anything in particular you came to love about the game as you worked so closely with one of its champions and were watching so much of it on a weekly basis?

GIL:

Oh, exactly. Number one, to me it became almost a perfect sport of, of course, athleticism, but you must be a problem solver. You must be a little bit of…some kind of geometry, or you must understand angles and spins and velocity. And how you create spin with that slice—man, all those things that I just said, “This is amazing that they can do this.” Our guys would have the ability, like an Anderson Hunt, to shoot from so far out and make it go into the hoop, it’s a marvel. But then again, if they’re having difficulty doing that, toss it in to one of the big boys and have them just thunder-jam that thing home. And we did. But one person has to do all of that problem-solving out there, and literally on the run. And you have to have that quickness, the reflexes, the demeanor, the disposition, the ability for a mental analysis as well as physical during the matches out there. That’s when I really became such a huge, not only fan of the sport, but a student of the sport. Having the ability to cross paths with so many of the great athletes—but once again, Andre, he was a special education for me in the sense that, I always said, “This is you, you’re made for this, you have such an understanding of what you want to do out there.” And then Andre would tell me, “Here’s what I’m going to do against this guy or that guy. This guy’s gonna do this. So I have to try to do that,” and then I would sit up in the stands and watch exactly that. [Laughs]

GIRI:

What are the most common issues with movement that you notice and that you emphasize in your training after working with Andre?

GIL:

I’ve learned this from Andre just so vividly: speed and quickness. Okay, so you’re getting from ad side to deuce side, so you’re on one side of the court, man, you’re really quick getting to the deuce side. Man, you can run for that forehand. Yeah, well, that’s only half the problem. You got to get out of there. And Andre would teach me about specific players, he’d say, “That guy’s really quick, but he’s late.” I said, “What does that mean?” And he said, “Getting there is no problem for him. It’s just planting those legs.” Not stopping with the knees stiff, but rather bending the knees. And once again, the vivid example that comes to my mind always is Roger Federer—he’s like Baryshnikov out there, that fluidity. Andre would say you can’t get there and jam on the brakes.

Just like a defensive back might, covering a wideout. Or the two guard or point guard on defense, you have to be ready—they’re gonna drive right by you. So it has to be strong hips. The hips and the quadriceps. So in training, you just can’t train them for that quick burst one way. Andre had once said it when somebody asked him, “Why are you running better? Man, I see you have a better start—you’re running better.” And Andre said, “No, I’m actually stopping better.” And that just shows you how much thought goes into it. You have to really know how to stop better, and that takes strength. And you have to know how to move, muscularity-wise, with strength training along the way.

I speak at conferences and people ask me, “Yes, but lifting weights and getting stronger will make you slow, won’t it?” And I say, “Have you ever been to a track meet? Ever seen the physiques on those sprinters? You were implying that being strong makes you slow. The fastest humans on earth are strong. And they spend as much if not more time in the weight room than anybody else. And they’re the fastest humans on earth.” “Yes, but then if you lift weights too much, you’re going to get stiff and muscle-bound and you’re not flexible.” I say, “Have you ever been to a gymnastics meet?” “Yeah.” “Have you ever seen the physiques on these guys that do the iron cross or the pommel horse or the uneven parallel bars? Their physiques are amazing.” Yeah, so that notion, if you’d asked me, I would put the hammer down and say, “That’s not true. That is disproved anytime you go and look at the fastest humans on earth and then the most flexible humans on earth.”

Buy Now

Issue No. 13

Our photography issue features work by longtime collaborators—Fashion and Style Director Radka Leitmeritz goes to Vegas to capture desert style and tennis guru Gil Reyes and Gorilla vs. Bear’s David Bartholow, who has been capturing the tour in Polaroid. We’re pleased to present Stefanos Tsitsipas’ first published collection of photography. Gerald Marzorati and Louisa Thomas commemorate their favorite tennis photographs of all time all behind a striking cover of Daniil Medvedev by Samantha Hellman.