Fifty years ago, the Open Era of tennis began inauspiciously on the damp southwest coast of England.

By Simon Cambers

About 100 miles southwest of London, West Hants Lawn Tennis Club sits in a leafy suburb of Bournemouth, a coastal resort best known for its high proportion of retirees and eight miles of near-perfect sandy beaches. The club, which has 21 courts, including 10 American clay, has been revamped over the years and is now one of six high-performance centers in Britain, a place where many leading juniors dream of becoming a star. What most of them probably don’t know is that what sets West Hants apart is its history, its heady days echoing from the photos that adorn the walls inside the clubhouse.

It seems remarkable to consider now, but this was where “Open” tennis officially began, after the tennis authorities belatedly deigned to allow the professionals—those who were officially accepting prize money—to join with the amateurs, who were, in theory, paid expenses only. However, the amateurs were actually being paid handsome appearance fees to play. But by retaining their amateur status, they were allowed to play in the four Grand Slam events and Davis Cup, while the professionals were excluded. Hindsight makes it all the more ludicrous, but it took a visionary chairman of the All England Club, Herman David, to instigate the change. It started when Wimbledon held “Wimbledon Pro,” an event for eight top professionals—Rod Laver, Ken Rosewall, Lew Hoad, Pancho Gonzalez, Andres Gimeno, Fred Stolle, Butch Buchholz, and Dennis Ralston—shortly after the 1967 Championships. Shown live on BBC Television in glorious color, the event included a promise by David that if they filled the stadium, which they did, they would be allowed to play in the Championships the following year. The official announcement later that year, made in conjunction with the equally progressive British Lawn Tennis Association, prompted the other Grand Slams, soon after, to follow suit.

It was on March 30, 1968, that an extraordinary general meeting of the International Lawn Tennis Federation, then the governing body, finally ratified the return of the professionals. And so, by virtue of its late-April spot on the calendar, the British Hard Court Championships, which began at 1:43 p.m. on April 22, 1968, were the first Open tournament. As John Barrett, a former British Davis Cup player who later became a revered television commentator, wrote in the Financial Times in 2006: “I shall never forget the feeling of elation as we gathered at the West Hants Club. At last the game had been set free. At last we could all be paid up-front instead of having a brown envelope passed to us in the tournament promoter’s car.”

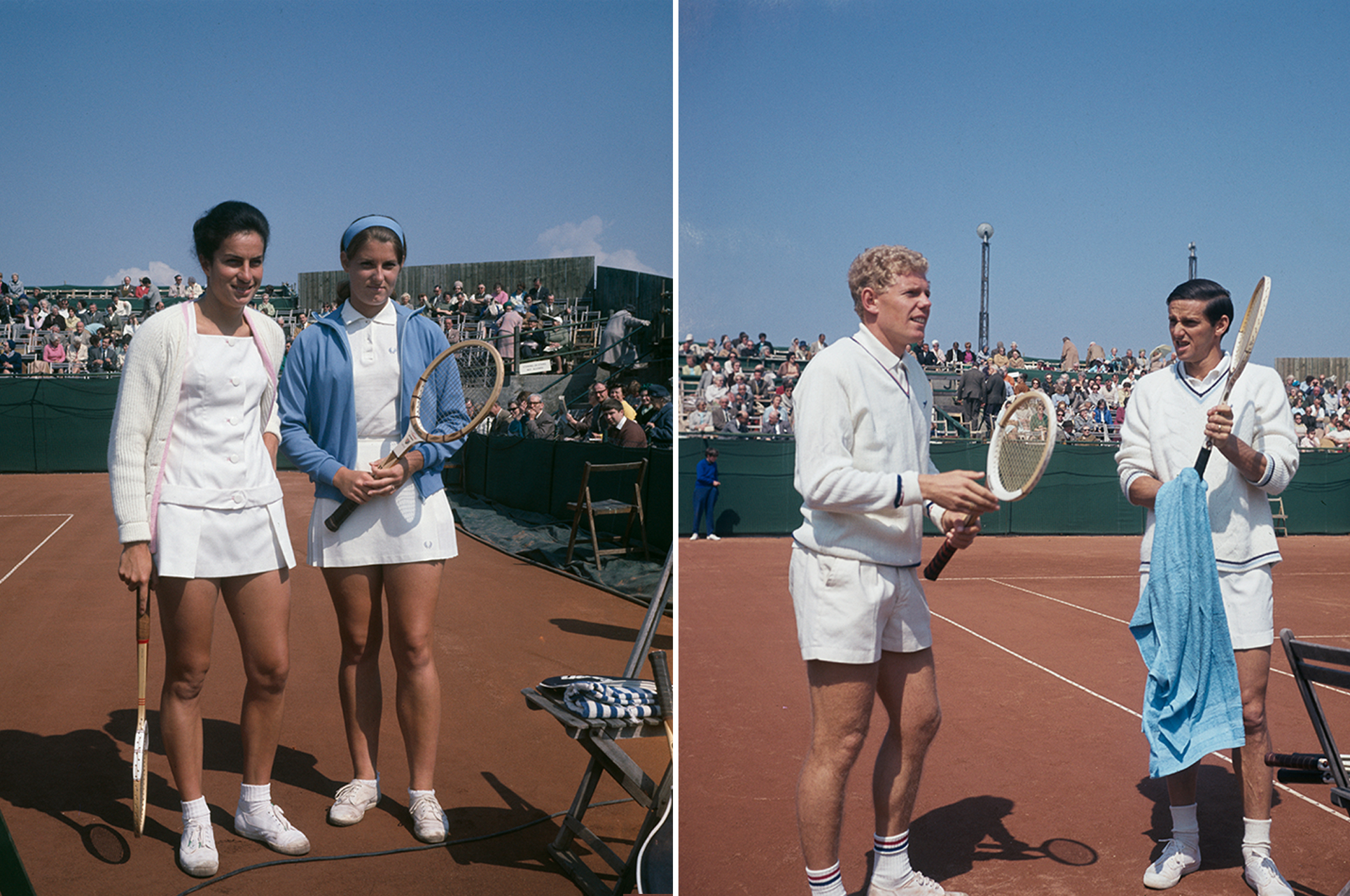

In 1968, the British Hard Courts were considered almost on a par with the likes of Monte Carlo and Rome, two events that have long surpassed it in importance. Before World War II, Britain’s Fred Perry won it in five consecutive years, while Hoad, Roy Emerson, and Laver had been regular visitors in the 1950s and ’60s before they turned professional. But tennis had been starved of these big names for several years by the time West Hants opened its doors in 1968. While the so-called Handsome Eight—a group of professionals including John Newcombe, Tony Roche, and Niki Pilic—chose not to play and Arthur Ashe and Manolo Santana were also absent, the arrival of a host of champions, including Laver, Emerson, Rosewall, Gonzales, and Stolle, caused a real stir. Equality was a long way off just yet, though, with the men playing for a first prize of £1000 ($2,400 at the time) and the women competing for just £300, a differential that explained the absence of the professional women, led by Billie Jean King and Rosie Casals. Television, which had entered the color age in Britain the previous year, was there, and so were numerous newspaper reporters from around the world, all eager to see how the amateurs would cut it against the hardened pros.

For some, though, there was a feeling of animosity in the spring air. “I think there was a buzz, probably more for the pros than for the amateurs, if you can call us pros,” said Laver, recalling his memories during a quiet moment in Melbourne earlier this year. “I think we all knew that the pros were better than the amateurs and a lot of the amateur officials didn’t want to believe something like that, so I think the amateurs took sides during that tournament. We as the pros were left sort of hanging, thinking this should be a tournament where everybody got along. I think [some of] the amateurs felt we’d ruined tennis.”

Rosewall had never played in Bournemouth before, so arriving in early spring was an eye-opener. As Virginia Wade, who won the women’s event, said in an interview this summer: “Bournemouth is beautiful if the weather is good, but that’s a big if.” But Rosewall, who had turned professional in 1957 at the age of 22, was as enthralled with the situation as anyone. “Being one of the older pros, for 11 years we missed out playing in any of the major events, including Davis Cup,” he said in an interview in the “Last 8 Club”—a private lounge at the All England Club open to anyone who has ever reached the quarterfinals at Wimbledon—this summer. “So we were pretty happy with the situation. It was really going through a learning curve as far as the promotion and the marketing of the events. There were a few conflicts with the contract professionals and the different groups that were trying to have professional matches. It was pretty exciting to have the chance of getting back into events. Everybody was on tenterhooks to see how we’d play with the amateurs involved. They were saying, ‘Oh, the professionals might dominate.’ Then Mark Cox beat Gonzales and Emerson. That created a real big storm.”

Cox, a Cambridge University graduate, was a 24-year-old left-hander who was much more used to the slippery clay courts. “It was called British Hard Court because it wasn’t grass, but they were shale, rather than hard courts [as we know them today],” said Richard Evans, the esteemed journalist and author of Open Tennis. Cox had been making a living as an amateur, a situation Herman David called “a living lie,” shamateurism. “People within the game realized it was absurd,” Cox said in an interview this summer. “The Italians were paying their players substantial amounts of money to play Davis Cup. Other countries were doing it too, but the Italians were paying a lot, under the table, one way and another. It was hypocritical and also to the detriment of the game.”

Cox and other amateurs had been happily playing on expenses while being courted by promoters around the world, who offered them big money to play in their events, sometimes doing the bidding during Wimbledon itself. “There was this thing, the Players’ Tea Room, which existed between [the old] Court No. 1 and Centre Court, near to the referee’s office,” Cox said. “Many of the tournament promoters, during the second week of Wimbledon, were there, and it was a little like a bazaar, you might say. You could go up there and some of them wanted you and some didn’t. The expenses varied quite considerably—for the very top players, they would be substantial, enormous.” Cox’s favorite part of the year was the “Caribbean circuit,” which began in Philadelphia and went down into the Caribbean itself. “You got a weekly rate,” Cox said. “As far as I was concerned, everything was aboveboard, it was all declared from a tax point of view. I didn’t make any bones about it; I made money out of playing as an amateur and therefore when the opportunity came for the sensible course of action, Open tennis, I was supportive of it.”

If the professionals were under pressure to show they were the best, not all the amateurs were quite sure they were doing the right thing in playing together. There was a serious, if brief, threat that they would be expelled from Davis Cup because they had played against the professionals. None of the professional women came to Bournemouth, and when Wade won, she refused the winner’s check. “I didn’t accept the prize money because not only was it dramatically less than the men, but also because there was a big issue anyway in the very early days about what was going to happen with tennis professionally,” Wade said. “It sorted itself out very soon after that, but we didn’t want to burn all our bridges, so to speak. It wasn’t a major protest, but it wasn’t worth taking risks and also not being rewarded properly.”

Played over the best of five sets, the men’s tournament began in rain, denying Stolle the chance to make history. “I was supposed to play the first match in the Open era,” Stolle recalled in a chat in Melbourne. “But it rained—strange at Bournemouth, right?—and so the first match went on next to the clubhouse and it was Owen Davidson against John Clifton. They played the first match. Davo finished first, so he was the one who finished the first match in the Open era, in Bournemouth. It was always cold in Bournemouth.”

While Laver and Rosewall cruised through their early rounds of the 32-man draw, Cox struck a massive blow for the amateurs with his shock second-round win over Pancho Gonzales. A few weeks shy of his 40th birthday, Gonzalez would surely have won more than two Grand Slam titles had he not turned professional in the 1950s. When he won the first set 6–0 against Cox, it looked like the pros were sending a message, but the Briton produced the upset of the tournament when he came back for a famous victory. “He was a big guy, big reputation and also known to be quite a fiery character. I suspect I was overawed by playing the great Pancho,” said Cox. “Eventually I sort of got into the match and figured I had a chance of winning. He led two sets to one, as I recall, and he got a little bit tetchy in the fourth set. I seem to remember there was a net cord. He didn’t hear it, the umpire didn’t hear it, but I asked the linesman and he said it had been a net cord. I think that slightly upset him. I suppose he got tired and he didn’t like the courts particularly.”

Cox, whose smooth voice and insightful commentary made him a popular part of the BBC’s Wimbledon coverage after his retirement as a player, said the pros were on a hiding to nothing, but he reveled in a victory that made him big news. “It was huge,” he said. “I think there was even a photograph of myself on the front of The [London] Times, which didn’t happen too often for sports people in those days. It was a little bit out of proportion in a way, but from the point of view of its impact on tennis and the future of tennis, it was necessary, too, that the barriers between amateurs and professionals were broken down and the notion of shamateurism that existed [was removed].”

Others also drew attention. Welshman John Williams, better known as J.P.R. Williams, later became one of the greatest rugby union players of all time. Williams lost in the opening round to Australian Rob Howe, who won four Grand Slam mixed doubles titles. Years later, Williams told The Guardian he spent his £20 first-round prize money on drinks for his rugby teammates. Stanley Matthews Jr., the son of one of England’s best-ever soccer players, Stanley Matthews, won the opening set and led 3–1 in the second against the great Andres Gimeno, the Spaniard who won the French Open four years later. Matthews Jr. later struggled as a professional and told The Guardian in 2007: “I was a serve and volleyer with a weak serve.”

And then Cox beat the great Roy Emerson. “That was quite a surprise,” Cox said. “He was one of the best athletes. I think he used to run into the waves of Bondi Beach and then do 200 kangaroo jumps, those double-knee jumps. He was a phenomenon. He’d play five-set singles, five-set doubles, and mixed doubles day in, day out. But we were used to playing in that humid, dank, dark climate of Bournemouth in the spring, whereas they’d played most of the time in indoor halls on good surfaces. He was one of the fastest movers on the court, but on the slippery shale his feet were moving so fast, he had no traction. I think I won the first nine games. The court certainly didn’t suit his style of play, and fortunately I managed to squeeze through in the third set.” The win made the headlines. “By beating Emerson, Mark Cox became a hero,” Clay Iles, who also competed in the event, wrote in Tennis Pictorial International at the time. “His photograph was on many front pages. And his proud wife was subjected to countless probing questions.” Emerson remembers the match in simple terms. “I was beaten fairly badly by Mark Cox,” he said in Melbourne this year. “It was the first Open. I love Bournemouth, but it is cold.”

Cox’s luck ran out when he met Laver in the semifinals. “I guess I was Mark’s downfall,” Laver said. “That was an education in how to play tennis,” admitted Cox. The Briton was later called on by the Australian to train with him before he played Jimmy Connors in 1975 in a $100,000 shoot-out in Las Vegas. “He was very good to me, Rod,” Cox said. “He needed a left-hander. That was an eye-opening experience, in terms of his dedication, hard work, his specificity, how he would work on every aspect of his game, the focus and determination he had. I spent several weeks with him. Soon after that, I won the first two tournaments I played and I earned more money in one month than I had in my entire life.”

Rosewall took out Gimeno to reach the final without losing a set, and while others were slipping everywhere, Rosewall remained fleet of foot. “It was a difficult tournament because a lot of [the pros] were not used to the slippery type of clay court,” he said. “That’s what I learned on, so I was, generally speaking, quite happy to play under those kind of conditions, as long as it wasn’t too cold or too wet.” Laver won the first set of the final, but Rosewall danced his way to a 3–6, 6–2, 6–3, 6–0 victory to etch his name in history. “When we went to play in the final it was kind of like, just another match for Rod and I, and then of course we got interrupted with the rain,” he said. “I was happy to win the event—nice memories, and it’s something that I mention quite a lot. Maybe there wasn’t a really top field, with many international players, but I was happy to be a winner and I often talk about being the one that won the first two Open tournaments, including Bournemouth.”

The second of those came just a couple of months later at the French Open, when Rosewall again got the better of Laver, before Laver gained revenge in the first Open Wimbledon. “When you’re playing in cold weather, with the grip, your hands, you lose all the feel,” Laver said. “I don’t know how come Rosewall didn’t lose his feel.”

As for the women’s victor, Wade was born in Bournemouth, and though she moved to South Africa with her family when she was just 1 year old, she returned at the age of 15. During the British Hard Courts, she stayed with an aunt nearby. She may not have accepted her prize money after beating Scotland’s Winnie Shaw 6–4, 6–1 in the final, but she knew the importance of her victory, in an event that saw well over 20,000 people attend over the week. “I always liked playing there, and it was always a sellout,” she said. “There was television so it was good exposure, and the centre court was very nicely done. It was a pretty big deal. It really was.”

The British Hard Court Championships have long gone—the last combined event was held in 1983, and an attempt to revive it in the mid-1990s lasted just one year. Tennis has come a long way in half a century, but whatever happens in the future, West Hants and Bournemouth will always have a special place in the game’s history.