By Giri Nathan

A friend’s dad once told me about a trick he’d learned from a good tennis player, maybe even a semiprofessional one. The tennis player had faced an opponent who showed up wearing a shirt that said “Eat Beer.” What did that mean? Nothing. That was the point. There was nothing there to decipher. It was only meant to make you wonder why that verb would be paired with that noun, and why they would ever be put on a T-shirt. It was meant to introduce that second of puzzlement, which would be a second that you weren’t puzzling out how to beat him at tennis, which would be an advantage. Sometimes I think of Daniil Medvedev as the living embodiment of that T-shirt. Strangeness inheres in his game. He hits shots strange enough to make me think, “Why?” and I have to think that the opponent, for all his ferocious focus, is permitting himself a second of “Why?” too, right there on the court, and that’s a second gone to waste.

There was a point late in the second set of the final of the ATP Finals that encapsulates the Daniil Medvedev experience. Dominic Thiem booms a serve out wide and Medvedev stabs it back, but it’s short, so Thiem comes in to snatch it out of the air with a big swinging volley into the opposite corner. He didn’t hit it hard enough, because all 6 foot 6 of Medvedev is sliding into its path, and with his back to the net he stabs again at the ball, this time a lob that sends Thiem trotting all the way back to the baseline. With both those attacks completely nullified, Thiem finds himself in a neutral rally on a hard court, which is not ordinarily a bad position for a terrific ball-striker like Thiem, but is a terrifying place to find oneself with Daniil Medvedev.

What ensues is a master class in trap-setting, arrhythmia, and discomfort. Medvedev doesn’t hit the same type of shot twice for the rest of the rally, mixing up pace, height, location, and spin on each as if toying around with the sliders on a control panel, just to see what happens. As I see moonball to the deuce corner, and moonball to the middle of the court, followed by drive to the corner, followed by loop to the middle, the “Why?” creeps into my head. What compels you to do this? Why so much air under the ball all of a sudden? Why hit there? From that position? My pedestrian brain is sitting right there alongside Thiem, who is doing what he likes to do, shot after shot: big spinny forehands that could end the point. But Medvedev looks like he would not protest if this point lasted for 15 minutes, exploring the full tool kit of odd shots. He looks happier to grind—to cover huge swaths of court in loping strides, over and over—than any other player of his physical dimensions. Thiem disrupts the sleepy exchange to hit an edgy backhand slice down the line, and then, suddenly, Medvedev springs awake. A stinging forehand crosscourt, which Thiem scrambles to return, followed by a junky forehand slice down the line, which Thiem scrambles to hit, only to watch Medvedev’s angled forehand nestle itself inside the other service box. Medvedev surely saw the path to that eventual winner even if I never will, and that is the unsettling joy of watching him play tennis.

Tactics aside, even his strokes call out for explanation: quick little snatches that leave a noodle arm encircling a noodle neck, producing one of the flattest balls on tour. I suspect no other living human could mimic that swing path and keep the ball in the court, let alone be the No. 4 player in the world. And if Medvedev is not the best hard-court player alive, he cannot be too far removed from that title. Last summer he played six straight finals. He did not look like he would re-create that success this year, with uneven results in the restart, but then he put together a last-minute 10-win streak to remind us how good he is. He won in Paris, then went to London, where he took the most convincing possible path to the title by beating world No. 1 Novak Djokovic, No. 2 Rafael Nadal, and No. 3 Thiem in succession. After he delivered the final unreturnable serve, he pulled a ball out of his pocket, hit it into the corner, pursed his lips into an amused frown, threw his palms up in a microscopic shrug, and walked toward the net. What’s one of the biggest titles in tennis, anyway? Who cares if it was the “toughest victory in my life,” as he would later call it? “I don’t celebrate my victories,” he said. “That’s just my thing.” Maybe after hard-court major No. 1, we’ll get those hands shrugging all the way, at shoulder height. What could be a more fitting victory pose for this guy than one of mild puzzlement?

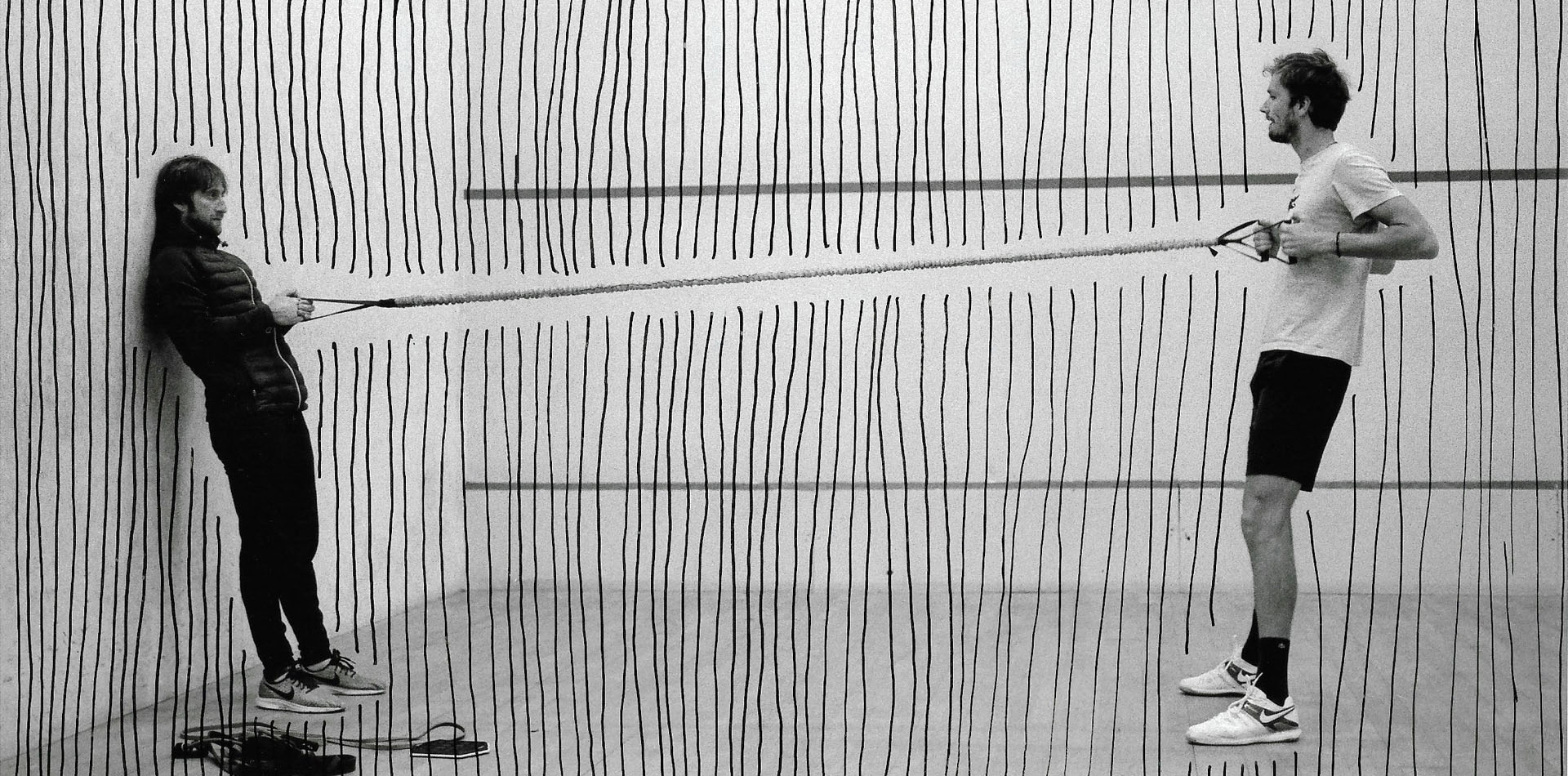

Above: Daniil Medvedev flips New York the bird, from Racquet No. 13. Agnes Ricart