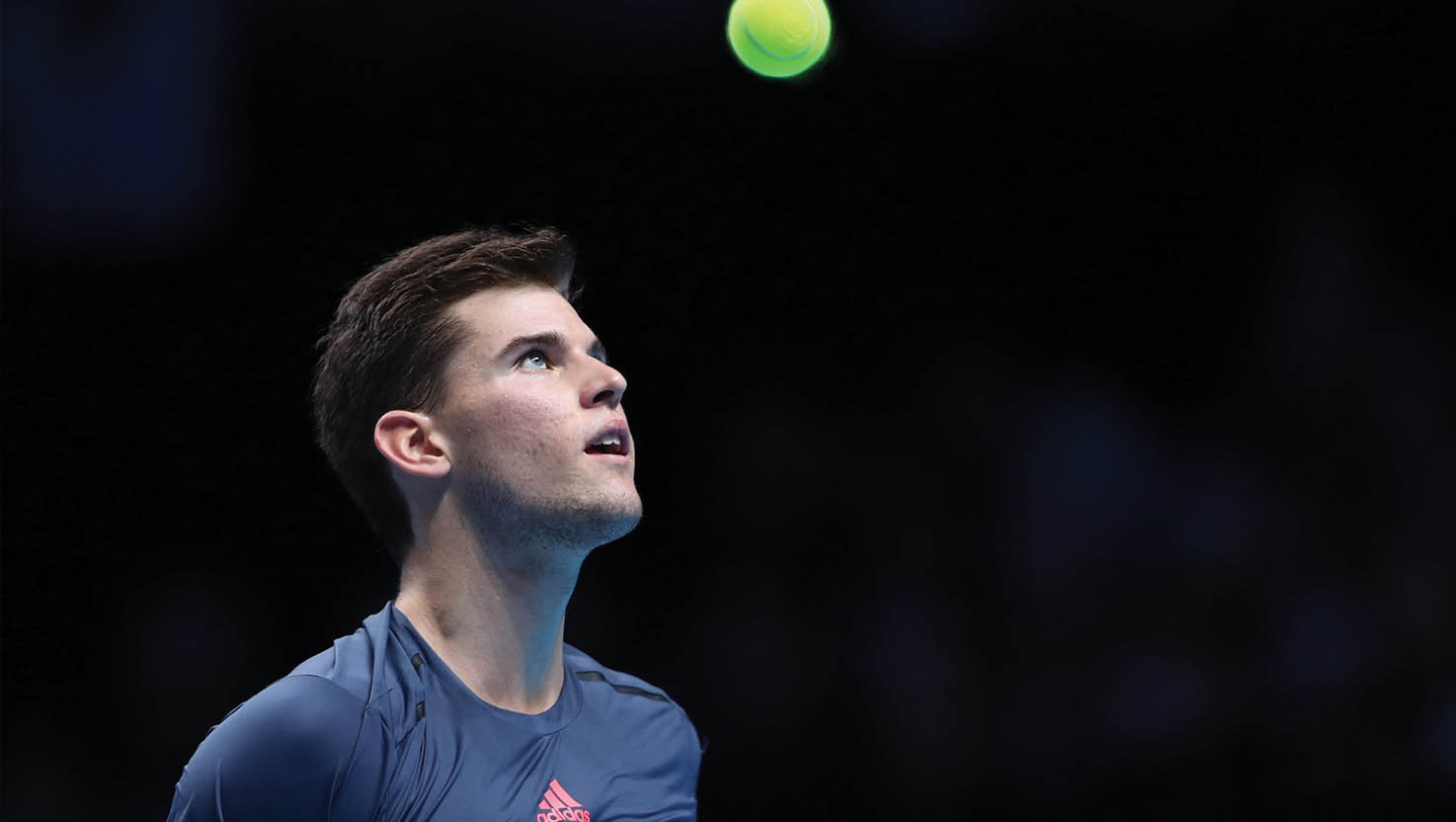

Dominic Thiem announced that he will retire at the end of the 2024 after falling short in his comeback from a persistent wrist injury. Below is an excerpt of a feature piece from Issue No. 2 by Ben Rothenberg.

Standing apart from a generation for whom questions about effort are endemic, Dominic Thiem may be The Boy Who Tried Too Hard.

On and off court, the 23-year-old Austrian is unceasingly earnest, and unceasingly switched on. Hollywood has made an Austrian accent indicative of a robotic lethality, and for Thiem, such Schwarzeneggerian allegories seemed appropriate. But as his breakout 2016 season wore on, it became more and more clear that Thiem was human, not machine.

Thiem had played constantly and won constantly over the first half of the year, with both quantity (four titles and a tour-leading 47 wins) and quality (victories over both Rafael Nadal on clay and Roger Federer on grass). But his unyielding drive ultimately stalled on him dramatically, and from Wimbledon on he won just 11 of 22 matches. Having been comfortably fourth in the race to qualify for the World Tour Finals in London, Thiem slipped to ninth in the standings, and made it in during the last days of the season only after Rafael Nadal withdrew and Tomas Berdych let a 6–1 lead slip in a tiebreak.

Thiem described his drop-off, fittingly, in mechanical terms.

“The system broke down a little bit,” he said of his post-Wimbledon fall. “Then it was tough to get it going again. It took almost three or four weeks, and then I realized that maybe it would be better to take time for regeneration. I got sick, and just not normal sick but it was a sign from the body that he needs a break. Even after I was healthy again I was not really, really pumped to go for practice. I was really tired—I just wanted to stay at home and to relax.”

But stubbornly determined as ever, Thiem blocked out the messages his body was sending and went to play a small tournament in Kitzbühel, Austria, where he would lose his first match in straight sets to 421st-ranked Jürgen Melzer.

“So even though the body showed me somehow that I should rest a little bit, I pushed to the limit, because I wanted to play well in Kitzbühel,” Thiem said. “I think this was even a bigger mistake; because of this I got, maybe, a hip injury, and I got even more tired, so it took a longer time to recover.”

Though he spoke as though lessons had been learned, similar mistakes were repeated. After pulling out of his fourth-round U.S. Open match with a knee injury, Thiem piled on another heavy schedule for the fall, traveling from Metz to Chengdu to Beijing to Vienna to Paris, with limited success.

While his unceasing drive has recently proved a liability, it is also the foundation of his success and the engine for the future. His coach, Günter Bresnik, has worked with players dating back to Boris Becker and Henri Leconte, but takes perhaps the most pride in his work with Thiem, which led him to publish a book called The Dominic Thiem Method.

Bresnik has had Thiem under his wing since he was only 9 years old, an age at which a young, porous mind can absorb lessons in innate ways that have proved ultimately impossible with established ATP stars like Bresnik’s most recent former charge, the fickle Ernests Gulbis, who Bresnik said left him feeling “like I failed” after he was unable to win a Grand Slam title or reach the top five under his guidance.

“Gulbis is probably a much more talented player, or more gifted from Mother Nature, than Dominic,” Bresnik said. “But he’s missing a lot of tools which I think you can’t teach somebody. Because of his upbringing, he’s not going to go as far as somebody who does something really right. The passion for your profession, how much you are prepared to sacrifice for your job, what you are prepared to give up in return for succeeding in what you really like—it makes a huge difference compared to other people who want to be successful tennis players but also want to have a nice life, to go for holidays for weeks out of the year. They want to have a girlfriend and nice cars.

“If you have one goal, and you put all the other goals and wishes aside, I’m very convinced that you’re going to reach it, no matter what it is. But most of the people, they downgrade the word ‘goal’ to a wish. Dominic, for me, is the kind of person who is prepared to do whatever it takes. The other guys as well: Federer, Nadal, Djokovic, Murray—who are much better tennis players than Dominic—they also have this mentality. They’re thinking 24 hours a day, for many, many years, only about tennis.”

The four players named by Bresnik belong to a generation or two ahead of Thiem’s, and no one younger has been able to mount a significant breakthrough to join them. Bresnik thinks the distractions of technology may have played a role in holding back this younger cohort.

“To be nonstop on the phone even in a changeover at a practice?” Bresnik said, incredulously. “This is, for me, unbelievably disturbing for them to always have to consider if the girlfriend sent a photo from holidays or whatever. It’s nonstop. And at breakfast, they don’t talk with each other anymore.”

With this Luddite-leaning ethos, Bresnik briefly brought in outside help in the form of fitness coach Sepp Resnik, a grizzled man who has told tales of Rocky IV-montage-caliber training in the mountainous, wintry forests of Austria. Thiem has downplayed the impact and disputed the details of Resnik’s work with him, but that Bresnik welcomed his help fits with the coach’s emphasis on limitless striving.

Bresnik cites Thiem’s strict parents as a key to his development—“The number-one people who destroy careers of kids are the parents,” he says—but also credits his own “handwriting” as having been etched into Thiem from his first days on the court.

“He’s the only guy who never, ever asked me how much longer practice is going to take,” Bresnik said of Thiem. “I practice with him and he doesn’t ask when we’ll finish, and after two hours he didn’t ask me, and after three hours he didn’t ask me. This, over a period of 15 years, is pretty impressive.”

Top: Illustration by Mads Berg

For Bresnik, such quantity is a prerequisite for greatness.

“Like a virtuoso violin player—they practice six to 10 hours every day, and then it looks so easy,” he said. “They’re not more talented; they don’t play better because they are born like this. They play so good because they practice it harder. In tennis and all other sports, it’s the same. A doctor is much better if he makes 500 surgeries a year and others make only 200 surgeries a year. All over the world, it’s the same. To make Dominic able to handle the physical and mental pressure well enough to succeed in playing up with the all-time greats of Federer, Nadal, Djokovic, and Murray who are around now, you need also to prepare specially for it. I think it’s a must.”

Though one might expect Bresnik to balk at a player like Nick Kyrgios, whose own commitment to the sport is often questioned, Bresnik embraced him and drew a parallel between Thiem and Kyrgios. In fact, he thinks their contrasts could foster a rivalry of opposites like the one between Bjorn Borg and John McEnroe.

“I think they are very different, but they might seem more different than they are, because Kyrgios did not get to this level without working hard,” said Bresnik. “This would be unfair to Kyrgios, because he’s an unbelievably gifted player. What most people consider a weakness, this loose approach he has to the game, it’s also in certain departments a strength, because to come up with the shots he does is only possible if you approach your game as loose as he does.”

Thiem, more tightly wound about his sport, believes the payoff for his work is the release of victory itself.

“The feeling after you’ve made the match point, for the next two, three hours, it’s the best feeling in the world,” he said. “You’re feeling so strong, so confident. It gets even better when you’ve won a tournament.”

The hard-fought highs, however, don’t last.

“It’s really special in tennis, because if you win on Sunday a tournament, Sunday night is great, but then on Monday when you come to the next place, okay, everyone congratulates you, but that’s it,” he said. “Everyone is focused on the next tournament and your victory from last week is forgotten.”

With the ephemeral nature of success in tennis, and the grueling schedule he puts himself through, Thiem admits that the sport can get “unbelievably lonely.”

“You get crazy a little bit,” he said. “I think there is not one normal player on the tour. Every single one is crazy, also myself.”

Asked what exactly makes him crazy, Thiem paused, then smiled with a rare glint of mischief.

“I don’t tell it in the public,” he said, laughing. “But I think that the whole sport, and the whole lifestyle, it’s just something special. If you are really just an average guy, you couldn’t take it.”