From Sydney to Rome, Martin Mulligan Has Led A Singular Tennis Life—and Is Responsible For One of the Sport's Most Iconic Looks.

It is morning in Paris, Wednesday, May 24, 2017, the second day of qualifying for the French Open. Buses adorned with Novak Djokovic for Lacoste adverts are everywhere. The players already in the main draw, with their entourages in tow, are arriving this week to begin practice. Paris is beginning to percolate.

Martin Mulligan is staying at the Hyatt Regency Paris Étoile at Porte Maillot, formerly the Hotel Concord Lafayette, the longtime official player hotel, except now the hotel is in the middle of a massive renovation and is barely functioning. Blue tarps line the walls, it is a labyrinth of construction—but Roland Garros is still just a 15-minute taxi ride away, and at 77 years old, it’s not easy for Mulligan to change routine.

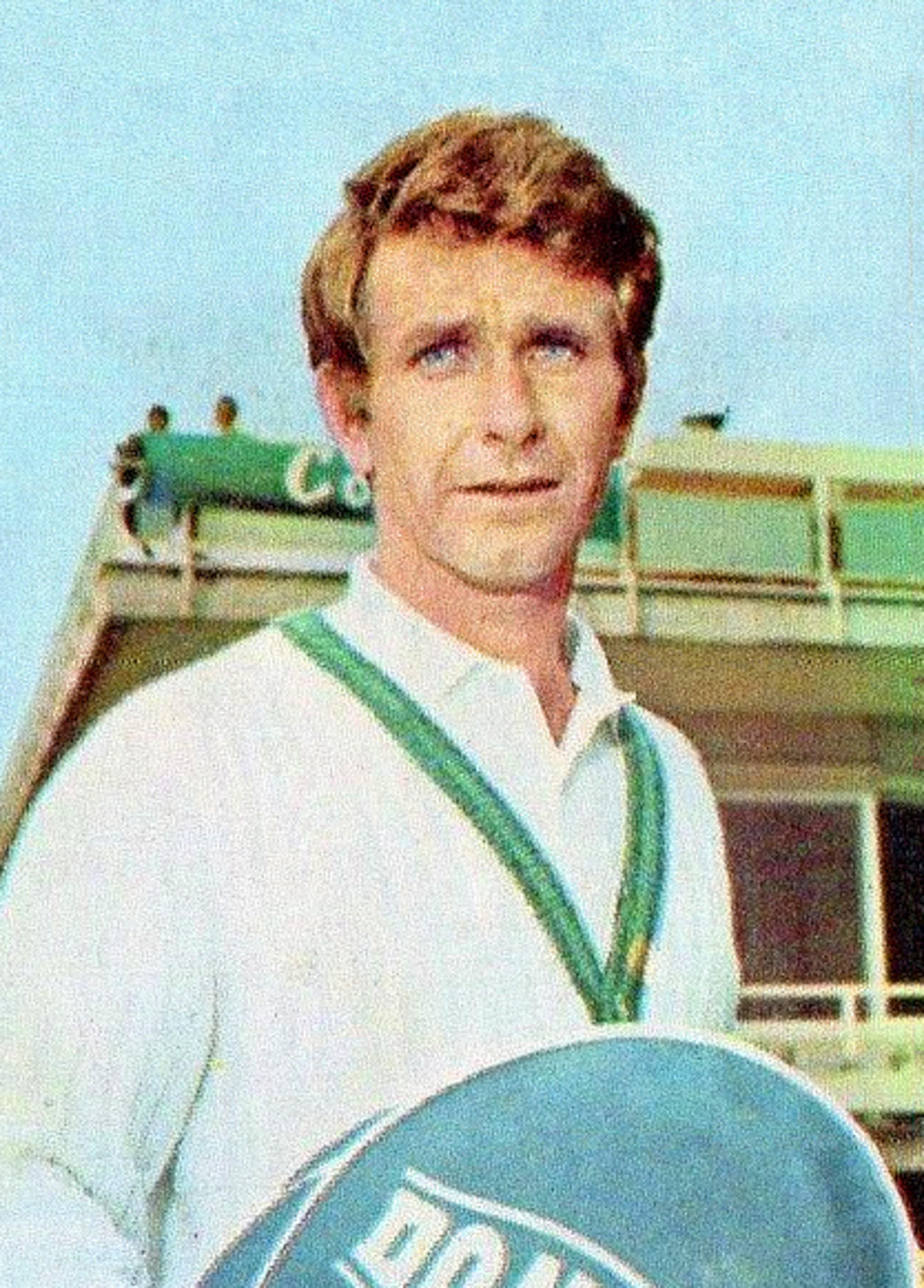

He exits the elevator smiling, moving with a familiarity that only a lifetime of doing this drill brings. He’s short, dressed like an American tourist, with a short-sleeved button-down tucked into jeans, but there are clues on his person as to who he is. His sneakers are Fila and he’s wearing a classic Rolex (a gift for playing Davis Cup in 1968). He walks with the bowlegged hobble that you earn grinding too many hours on the court. Connors has it, Agassi is getting it, Becker has it too. He’s probably needed a knee surgery for the past twenty years, but there’s no time for that now. He may have to fly back to Italy, for example, to deal with the grass-court shoes, to make sure there are no nubs visible from the top of the shoe (otherwise he’ll have a big problem with the All England Club), or back home to San Francisco before Wimbledon in July. He was just honored for winning Barcelona 50 years ago, and they’ll do it again in Bastad, Sweden, after Wimbledon. He doesn’t want to go, but I say he should, that he certainly will never be invited there again. His blue eyes shine as he laughs and agrees.

We make our way to the taxi stand; he needs to pick up his credential, and we may as well do the interview next to the court where he had match point on Laver in ’62, he reckons.

“The first time I came here was with the Australian Davis Cup team in 1959.” He looks me square in the eyes, does the math that there will have been 232 Slams played since then, and is certain that he has been to over 225. He knows he hasn’t missed more than seven. “I don’t know if that’s something to be proud of or if it says you’re an old fart. But you’re only as old as you feel. Y’know?”

He speaks with an Australian accent, and his dulcet voice makes you feel good. But there’s something else there, some other intonation that lives in his voice that is derivative of a life on the move. It’s most noticeable in the way he enunciates his t’s. His phone rings and he switches to Italian. Something about the grass-court shoes.

Mulligan won the Italian Open three times in the ’60s ,[1]when it was best of five sets, and reached a career-high world No. 3 in 1967. He has been the head of the pro tennis player program for Fila since its beginning in 1973, but that’s only one small part of this story.

Longtime ATP attaché and de facto Italian tennis historian Vittorio Selmi summarizes: “He moves very anonymously and we remember him as a top player, but his life in tennis goes way beyond his achievements on the court. It has been an amazing life in tennis.”

When we arrive at the accreditation tent he tells the ladies his name and they roll their eyes and giggle—they have likely seen him on this day for the past 20 years, maybe 30, when they first began working for the French Tennis Federation as teenagers, and have known him as the nice guy from Fila. My guess is that, like most in tennis, they have no idea that he was once a star player with his own signature racquet, shoe, and string.

We walk past Court Philippe Chatrier and take a seat at what will be an outdoor café in a few days once the main draw begins. I take out a 25-page copy of a detailed, color-coded statistical compilation of his entire career, a gift given to Martin by a loyal fan who happened to be a statistician.[2]The document is amazing in its detail; it is hard to know how long this could have taken to compile, but it had to have taken years. Just searching the microfiche to pull these results must have been a herculean task. There cannot possibly be another document dedicated to a tennis player like this in existence. The index reads:

1 Biography of Martin Mulligan

2 Career Summary in Chart Form

3–5 Alphabetical List of Lifetime Opponents

6 Davis Cup Record for Italy

7 Complete Wimbledon Record in Singles and Doubles

8–11 Tournaments Played and Round Reached

12–21 Singles Tournaments Results by Seasons

22–23 Career Five Set Singles Matches

24–25 Detailed Singles Record in the Grand Slam Tournaments

The Alphabetical List of Lifetime Opponents section is encyclopedic, a history of tennis names spanning the late ’50s, the ’60s, and much of the ’70s. He seems to have beaten close to every person who holds modern tennis significance; many whose sons became great players (Krishnan and Dent), names that are now famous courts (Pietrangeli), tournament directors and owners (Dell, Buchholz, Pasarell, Palmieri), one is a legendary line of clothing (Sergio Tacchini). There are the Aussies: Emerson, Laver, Hewitt, Fraser, Newcombe, Hoad, Roche. There’s Nastase, Ashe, Borg, Metreveli, and Amritraj. There’s Bobby Riggs, John McEnroe’s childhood coach Tony Palafox. The Manolos—Orantes and Santana—are there too.

I notice Martin dominated the Romanian Ion Tiriac (13–5), the Al Hrabosky[3]of tennis, the menacing Svengali who managed Nastase, Vilas, and Becker. Now a billionaire, he’s the owner of Bank Ion Tiriac, and some of the biggest tournaments in Europe. If you let your eyes travel into the crowd behind the court, his unmistakable handlebar mustache is still omnipresent at the Slams and most of the bigger tournaments. When I mention this, Martin perks up and then offers a peak into the importance of sport during the Cold War. “Now, that’s a guy that’s been around a long time too, because I played him in Italy in ’64. And I was going out with an Australian tennis player, a pretty girl, and he asked me if he could play mixed with her because if he could, it would help get him out from behind the iron curtain. I said no problem because I didn’t like to play mixed.” We talk about whether Tiriac could have attended as many Slams as Martin—we decide impossible, even Tiriac doesn’t attend Australia. I ask him if he has a relationship with Tiriac now.

“We say hi, [but] he was an unpleasant person on the tennis court. We used to have many fights on the tennis court because he was a cheater—a big cheater. But you have to think it meant so much for him to win to be able to get out of the country. For him maybe it was life or death; for us it was honor or glory and other things.”

The Biography page simply consists of one-line blurbs summarizing each year’s highlights laid out one after the next. Alongside 1962 it reads, “…in 27 tournaments, only once failed to reach at least QF…and in Paris held match point against Laver who went on to complete the Grand Slam. Ranked No. 6 in the world.”

I ask him which court he played Laver on. He points straight ahead. Chatrier. “Of course, stupid question,” I think to myself.

“It was two sets to one to me, 5–6, 30–40, and the guy serves the second serve and comes to the net, and I had a forehand. I could have either gone crosscourt or up the line. I went up the line, he covered and hit a backhand volley for a winner. I didn’t have another match point; I lost the set 10–8 and then he won the fifth set easy. But that happens.” It was the only time in the two years that he won the Grand Slam that he had match point against him. I detect a lighthearted annoyance with having to rehash that point. “It would have stopped his first Grand Slam, you know…but that’s how it goes.”

Five weeks later at Wimbledon, save for a brutal third-round five-setter with American Dennis Ralston, he burned through the draw to the finals. It would be Laver again.

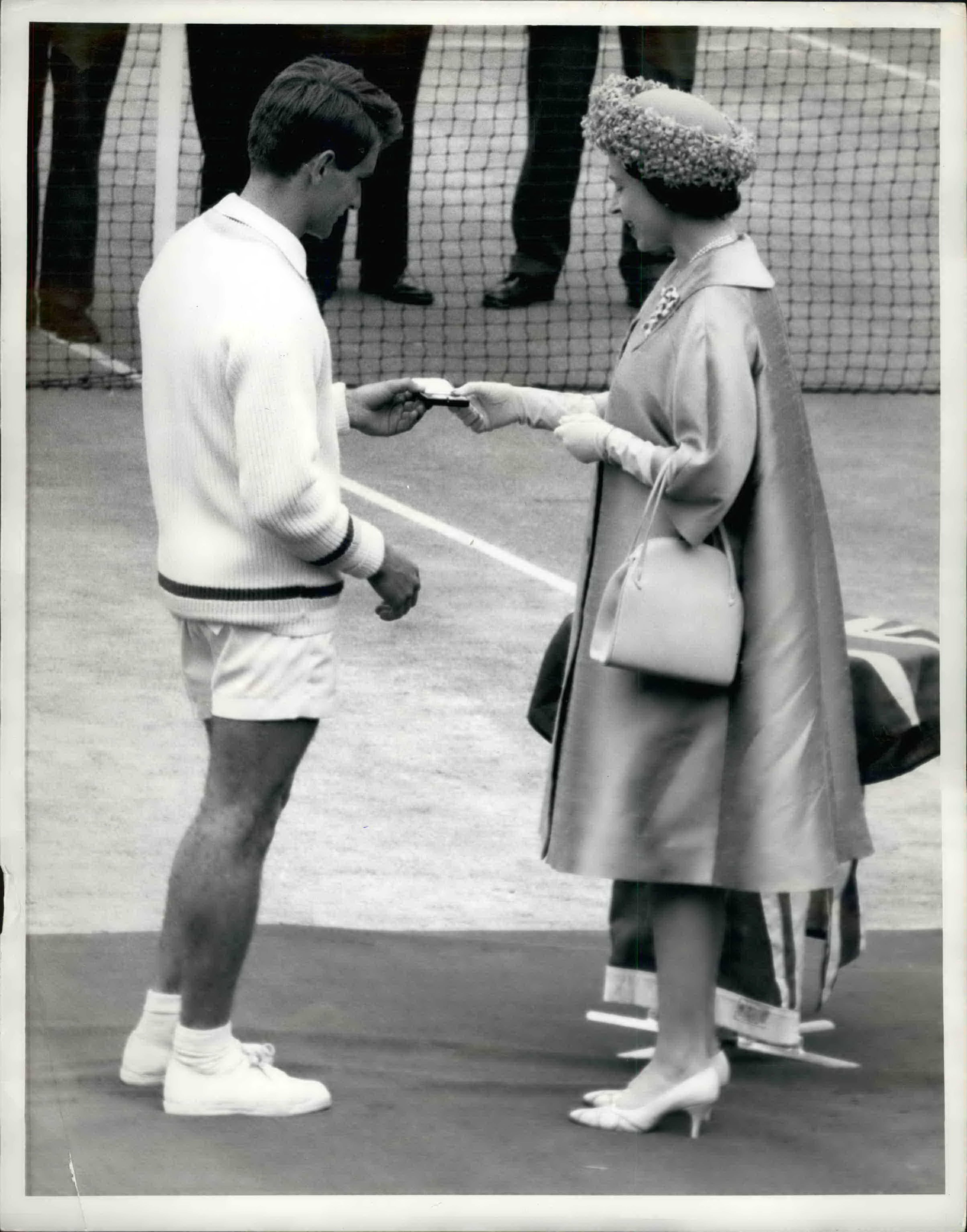

“We came from here [Paris], we had played at Queens, and he wanted to beat the shit out of me. And everybody said, ‘Aren’t you nervous?’ and I said no. [Then they] take you to an empty dressing room, okay? And they say take 10 steps, turn around, and bow to the Queen.” Yes. The Queen. Both Martin and Queen Elizabeth were making their debuts at the Wimbledon final, and the nerves came quickly. “Being from a British commonwealth, she was like the god. And then he broke me in the first game, and that didn’t help.” 2–6, 2–6, 1–6 was the score, earning him 100 pounds sterling, a smallish silver plate, and a pleasant conversation with the Queen, who had done some royal reconnaissance and took a little extra time to softly recruit Martin to come play for England.

They each received 100 pounds from clothing company Fred Perry for wearing its clothes. That wasn’t all they were paid, and he explains the under-the-table payment system, which was the modus operandi until the ATP and WTA were created in the ’70s.

“With the Australian Federation, they worked out a deal with the All England Club. We went as a group of Australians and then they’d say we want x number of thousand dollars for the Australians. Then there was the Australian delegate to the ITF, then he’d break it up how he saw fit. He’d decide Roy Emerson gets 12 percent, Rod Laver gets 20 percent, John Newcombe gets…and there was no fighting because you were happy to play the tournament. You needed the money, but you didn’t play for the money.”

We make our way out of Roland Garros to the Boulevard d’Auteuil, and walk far too long to the taxi stand at the corner of Avenue Gordon-Bennett and decide to go for lunch at Le Relais de l’Entrecôte, a steak frites joint by the hotel.[4]We arrive just in the nick of time, as they close at three. There is basically no menu, it’s a portion of steak with the most delicious mustardy au poivre and wonderful frites. As we dig in we again scrutinize the History of Martin Mulligan document.

Next to 1964 it reads, “Following a dispute with the LTAA, decided to live in Italy where he joined the Virtus Club in Bologna for whom he played until 1968.”

In 1960s Australia—in all tennis-playing countries, for that matter—representing your country in Davis Cup was as important as playing the Slams, and the federations held huge controlling interest over the players. While the times have changed, the part of the story that stands the test of time is that Martin was being screwed by his coach, the now-legendary Harry Hopman.

“Look, in ’62 I was number 7 in the world and they picked the seven-man Davis Cup team and I wasn’t on the team. In ’63 I won the Italian, I was in the top 10, and they picked the team and I wasn’t on it. In ’64 I won Hamburg and Monte Carlo and I wasn’t picked. So in ’64 Pietrangeli[5]said to me, ‘Listen, why don’t you come and play doubles with me?’ because he played with Sirola,[6]and Sirola had stopped playing tennis. He said, ‘You can be under the control of the Italian Federation.’ So I said, ‘Well, shit, I’m never going to play for Australia,’ so I said, ‘Why not? Okay.’” After all, he had Italian grandparents.

Rules of immigration and emigration, working visas, etc., seem to have been different back then, and by the sound of it, there was an anything-goes immigration policy, especially as it pertained to high-level athletes.

With one Italian Open championship under his belt, as well as many other match wins all over The Boot (Catania, Palermo, Naples, Reggio), Martin had already had a taste of la dolce vita, but no one believed he was of Italian blood. Athlete defections to greener pastures had become de rigueurin Italian athletics, and they coined a name for it. “At that time there was a big thing called Oriundi. In soccer, Italy got an Argentine player named Altafini, and Altafini said he had Italian grandparents and nobody believed him. I did not have an Italian passport, I had an Australian passport, and I said I had Italian grandparents. In Italy they all thought that was bullshit, but it was true.”

The only proof given of the alleged Italian heritage was this, from Martin himself: “In 1969 we played an exhibition match in a place called Vittoria Veneto, and that’s right by the town my parents came from, and a lot of the people from the family came. And it was very nice.” Satisfied, I did not press.

In Italy he flourished. He had a signature Diadora shoe and a wooden Donnay racquet with his picture etched onto the racquet’s throat. He slowly learned to speak Italian and before long became Martino Mulligano. “I’d spend January and February at the Federation training center, and there was [Adriano] Panatta, [Paolo] Bertolucci, [Corrado ] Barazzutti, and [Antonio ] Zugarelli,[7]so I would play with them every day, so they used to make me speak in Italian. I was with them 24 hours a day and then they said, ‘One day you’ll just start speaking in Italian,’ and I said, ‘That’ll never happen.’ But then it happened.” He would win the Italian twice more, along with Monte Carlo, Barcelona, and others. In 1967 he went an astonishing 117–11, winning 17 tournaments, and reached the finals in 22, finishing the year No. 3 in the world. He played for the Italian Davis Cup team in ’68, going 6–2 in singles, and with Pietrangeli went 3–0 in doubles. The politics of the Oriundi would make that his first and only Davis Cup appearance. He was married at the Vatican Chapel, and had a daughter, Monica, and a son, my close friend Martin Jr.

In the mid-’70s, as Martino’s playing career was coming to a close, relationships he had made with Diadora and other Italian brands led to an interesting opportunity with an underwear company from Biella—a small town an hour from Milan in the north of Italy—that was trying to enter the tennis market. Like their undershirts, they had created a tennis shirt with no seam, as well as a tubular knit made of Egyptian cotton and warm-up suits made of lightweight Italian wool. And they had an eye-pleasing, soon-to-become-iconic logo. Their name was Fila, their colors were a deep red and blue,[8]and, maybe most important, they were flush with money and looking to sign players. They first locked in Panatta, but they wanted to enter the international market. Just as he had done for Diadora, Martin signed a young Swede with long hair and a two-fisted backhand who looked more like a soccer star than anything else, and he looked incredible in the clothes. I show Martin a picture of himself in a sport coat with Borg, who is wearing a white turtleneck with the Fila Fpatch right on its throat, a Fila V-neck white cable-knit sweater, and a leather jacket. Any other person would look insane in this outfit. Borg, as always, then, now, and forever, looks like the coolest guy in the whole world. I press him for Borg stories, but he seems to either be keeping them in his pocket, or maybe Borg really was the Iceman, going from practice to the court (I mostly sense the former—athletic omertà is strong in Martin). He remarks that the giant patch on Borg’s throat is what they still refer to internally as the Pro patch and that it was once in heavy demand. “In those days everybody wanted the Pro patch, the big patch, so the only thing that had the big patch was the warm-up. So what Macy’s did was they’d put the anti-theft tag through the patch because people would cut the logo off with a razor blade.”

I ask him about McEnroe, who in ’77 reached the semis of Wimbledon and won the mixed at the French as an amateur, in Fila, and then enrolled at Stanford, winning the NCAAs, in Fila. “John played at Stanford. He wore Fila all the time, he liked it. And also, he had a Mercedes to drive around, which was our North American president’s car, so he was happy.” Martin dealt with John’s dad directly, and John McEnroe Sr. told him that after the NCAAs he’d turn pro. The deal was basically done, but in a classic case of hubris, Fila decided to go into the racquet business, and they structured the deal for John to use their new Fila racquet. Martin explains to me that the racquet guys broke protocol, and instead of sending the racquets for Martin to double-check and give to the player, they hastily sent the samples directly to Mac. “We sent the racquet directly to John and they spelled it Macenroe, so I called him and said, ‘How do you like the racquet?’ and he said, ‘If they can’t spell my name right, there’s no fucking way they can make the racquet right.’ And he stayed with Wilson and signed with Tacchini.” Martin’s much less bothered by this loss than blowing match point against Rocket, or getting passed over for Davis Cup by Hopman, but I feel this sting from across the table. He tells another story of how the president didn’t listen and refused to sign a young Chris Evert. C’est la vie. We share a strawberry tart to close out lunch.

It was 1979 and Martin was made vice president and moved to San Francisco, where Fila set up its U.S. headquarters. By then Borg had won four Wimbledon titles and four French Open titles, and his signature warm-up suit was selling for $350 retail; the pin-striped Borg shirt was $90.[9]Fila was the most sought-after, most hard-to-find, coolest, most expensive tennis brand in the world. Martin says that the clothes were in such high demand that there were multiple break-ins at their warehouse in San Mateo, Calif.

In 1983 a 26-year-old Borg unexpectedly retired after an exhibition in Vegas, while Nike and Adidas entered the tennis-apparel market in a significant way.[10]And although Fila would never quite be the same—since the ’80s the company has zipped though multiple owners and is now owned by a South Korean company—it has remained current in tennis.[11]In addition to having 80 players and coaches wearing the brand on tour, it is the clothing sponsor for the Indian Wells Masters, Larry Ellison’s not-so-mini Slam in the desert, and its takeover at that tournament is reminiscent of being at the US Open in the ’80s when Fila was the official sponsor and no one left the tournament without at least an official Fila for the US Open tee. In addition to Borg, Mulligan notably signed Gabriela Sabatini, Monica Seles, Jennifer Capriati, and Kim Clijsters, and now has the always dangerous top tenners Marin Cilic and Karolina Pliskova. He also had Vilas and Becker, both of whom eventually defected to Ellisse, a move engineered by their manager and Mulligan’s old rival, Ion Tiriac.

I pay the check and we walk back across the street to the front of the Hyatt. He expects Cilic and Pliskova to play deep into the second week, so this will be his home for the better part of the next 20 days. Also, the juniors begin in the second week, and scouting juniors is his favorite. “I like to see the kids coming up. To see a junior player play, you have to see who the coach is, who the parents are…that’s the best part of it.” As we say goodbye, Martin is still debating whether or not he has to go back to the Fila factory in Biella to personally inspect the grass-court shoes, or if he can just do it remotely on Skype.

He was on a flight the following day.

Endnotes

(1) A record he shared with Thomas Muster for many years, and notable because at that time the Italian was considered the fourth-biggest tournament after Wimbledon, Roland Garros, and the US Open.

(2) Full disclosure, this passionate fan, Joe McCauley, was also a longtime writer for World Tennis Magazine, and used to compile the end-of-year world rankings for said magazine until, according to Martin, he was fired by the editor for not including any Americans in the top 10.

(3) Hrabosky, a relief pitcher in the ’70s and early ’80s, was a menacing character with a grizzly Fu Manchu mustache, and was famous for his histrionics on the mound, where he would furiously rub the ball like a sorcerer, then charge up the mound and stare down the batters before firing.

(4) If you ever find yourself in Paris during the tournament, I highly recommend you pop in one night to see a who’s who of players (current and former), agents, and coaches drinking cheap red wine and eating steak frites. Dip the bread in the sauce.

(5) Nicola Pietrangeli, the Tunisian-born, two-time French Open winner, was arguably the greatest Italian player in history.

(6) Orlando Sirola, born in Croatia, won the French Open doubles championship with Pietrangeli in 1959, and appeared in four Davis Cup finals, playing doubles with Pietrangeli.

(7) Basically the 1976 winning Davis Cup team.

(8) When asked about those colors, Martin explains to me that the colors were so precise that it was an ordeal to even replicate them for business cards, and that the colors have been “bastardized” as time has passed.

(9) The inspiration for the iconic shirt, Martin tells me, was the pin-striped uniform of the New York Yankees, after Fila designer Pierluigi Rolando took a trip to New York.

(10) In ’82 the Lendl Argyle shirt put Adidas in the apparel game, and in ’85 Mac signed with Nike. Ever since then, these two megabrands have dominated the tennis landscape.

(11) I ask Martin why they don’t release the exact same cottons and wool knits for the Heritage Collection, their homage to yesteryear. “The same knits are impossible today…. I don’t think we even have the machines anymore.”