By Joel Drucker

“We are in Transylvania, and Transylvania is not England. Our ways are not your ways, and there shall be to you many strange things.” — Bram Stoker, author, Dracula

On an overcast autumn Sunday afternoon in Bucharest, Romania, the fourth set had ended. Usually when this happens, the player who’s leveled the match is eager to charge forward, the loser of the set keen to slow down. Here, desires were reversed.

It was Oct. 15, 1972. This was the fourth rubber of the Davis Cup final, between the United States and Romania. America led 2–1, one set from winning the precious Cup for the fifth straight year.. Romania, runner-up a year earlier and also in 1969, hoped to at last earn a breakthrough victory that would likely be the greatest athletic achievement in that nation’s history.

This was the first time Romania had hosted the final. The entire country was excited. All over Bucharest, replications of the Davis Cup trophy were visible, everything from ashtrays to baked goods to baby dresses, pennants, and posters. A book about the team’s prior trips to the finals, titled It Would Have Been Beautiful, had sold more than 100,000 copies.

The winner of the fourth set was the Romanian, Ion Tiriac. Moments after he’d taken the final point, 7,200 spectators stomped their feet and resumed the battle cry Tiriac had orchestrated for days.

“TIR-I-AC! TIR-I-AC! TIR-I-AC!”

Tiriac’s opponent was Stan Smith. The rallies on the red clay—Tiriac’s surface of choice and the opposite for Smith—were arduous. But the time between them was even more challenging. Throughout the first four sets, Smith had been subject to Tiriac’s stalling tactics and skill at manipulating officials and commanding the crowd. As longstanding tennis journalist Richard Evans wrote in his book on the history of the Davis Cup, “It is no use imposing Anglo-Saxon ethics on people who have seen Goths, Bulgars, Turks and Nazis rage through their land over the centuries. It is not a coincidence that Count Dracula lived in the Carpathian mountains. The Romanians have survived because they have a great sense of humor but an even greater instinct for what it takes to survive. Sometimes that is not pretty and certainly not fair.”

Both players knew that the fifth set meant a great deal for the Americans. For even if a Tiriac victory would only level the competition at 2–2, the next match would pit Romanian Ilie Nastase against American Tom Gorman. The previous month, the churlish but compelling Nastase won the US Open, in the semis beating Gorman for the 10th time in 10 matches. While that win in New York came on Gorman’s preferred surface of grass, Nastase was a far better clay-court player than Gorman, arguably the best in the world (he’d win Roland-Garros the next year without the loss of a set).

Gorman waited in the locker room and wondered if he would soon play for nothing or everything.

Smith waited too. Usually calmer than anyone in tennis, he’d become rattled throughout the fourth.

“TIR-I-AC! TIR-I-AC! TIR-I-AC!”

It went on for five minutes.

America’s captain, Dennis Ralston, sat courtside. On the outside, he was calm. On the inside, Ralston was upset over so much of what had happened the past three days. Not for the first time that weekend, he felt a strong desire to kill Tiriac.

***

Davis Cup protocol held that this match shouldn’t even have been played in Romania. Since Davis Cup began in 1900, the previous year’s winner earned the chance to sit out the competition. Teams all over the world battled one another to reach what was called the “Challenge Round,” hosted by the defending champion.

But soon after Open tennis commenced in 1968, Davis Cup began to reform itself. It was decided that beginning in 1972, the winner would no longer await a challenger, but instead play through the entire season. For the 1972 American team, that meant hitting the road. Round one was easy, a short trip in March to the Caribbean versus a weak Jamaican team. Then came the heavy lifting—three away matches, all on clay in front of wildly partisan crowds. In early June, just after Roland-Garros but prior to Wimbledon, a trek from Paris to Mexico City. In July, it was off to Chile and, two weeks later, Spain.

Still, having won the Davis Cup in 1971, the American team assumed it would play the finals on native grounds. One afternoon at the ’72 US Open, Ralston ate lunch with a few of his team members. A familiar, friendly face came to the table, veteran journalist Bud Collins. “Well, boys,” Collins told the group, “looks like you’re going to Bucharest.”

Told this for the first time, Ralston was livid. Once again, jerked around by officials from the United States Lawn Tennis Association (not until 1975 did the USLTA drop the L). During his playing days, Ralston was issued many a reprimand, including suspensions for uttering profanity on the court—tame stuff even in those times. One such penalty kept Ralston from competing at a Davis Cup tie played in his hometown of Bakersfield, Calif.

The USLTA point man for the decision to play in Bucharest was its current president, Robert Colwell, one in a long line of old-school white men who treated tennis more like a plaything than the serious sport it had long been and the legitimate business it was attempting to become. The prime advocate for Bucharest was Tiriac, who argued that the new format should give Romania the right to host the finals, particularly since Romania had traveled to the U.S. in ’69 and ’71. With Tiriac even threatening to boycott the finals, Colwell acquiesced. This wasn’t the last time Colwell and Ralston would clash over the 1972 U.S. Davis Cup campaign.

Angry that Colwell had made the decision to play in Bucharest without consulting them, America’s six-man squad took a vote. Five said they didn’t want to go. The dissenter was Smith, who as the reigning US Open and Wimbledon champion held the equivalent of U.N. Security Council veto power. Smith dared his compatriots to face the competitive challenge. Off to Bucharest it would be. Nastase, delighted to play on his favorite surface at his home club, said, “It is impossible for the Americans to beat us in Bucharest. We should be 10–1 favorites.”

A 2013 New York Times article revealed another layer of intrigue about why the American team went to Bucharest. The writer, Matt Richtel, explored both the tennis tale and a three-sided angle that played out between President Richard Nixon, the Romanian government, and each nation’s relations with the Soviet Union. Perhaps the USLTA decision to head to Bucharest had also been influenced by Nixon himself and his desire to curry favor with Romanian leader Nicolae Ceausescu.

Romanian and American tennis players occupied paradoxical worlds. Tiriac lived in a country with an oppressive government that could probably instantly put him in prison. But when it came to tennis, Tiriac was Romania’s judge, jury, and executioner. Ralston occupied a country where his life was highly irrelevant to the nation’s leaders but was often micromanaged by ill-informed volunteers.

Years later, Ralston saw all that happened as a clash of values—good versus evil. But if it was easy to identify the white hats and the black hats inside the lines, everywhere else in those early years of Open tennis, the structure and values of the sport were splintering, such topics as economics, governance, and court conduct reflective of similar changes going on in the greater society. Were the American team members pawns, at the mercy of the crumbling oligarchy of such archaic organizations as the USLTA (and even the White House)? How was it possible for athletes like Tiriac and Nastase to earn a living in the West and still occupy a police state? The 1972 Davis Cup season was one of many events in the first five years of Open tennis that saw tennis’ autocratic leadership structure begin to unravel, at first gently, eventually loudly.

Then there was the Cold War, no longer at its high boil point of the early ’60s, when tensions in hot spots like Berlin and Cuba threatened to trigger nuclear apocalypse. Instead, the Cold War bubbled along in new ways, various forms of competition often serving as a proxy. The spring of 1971 marked the start of “ping-pong diplomacy,” a series of table tennis matches held in China between American and Chinese teams. The next year, Nixon became the first American president to set foot on mainland China and the Soviet Union. In the summer of 1972, American chess wizard Bobby Fischer took on his Soviet counterpart, Boris Spassky. During this period, dubbed “détente,” the Cold War appeared to be thawing.

As tensions eased around the world, America faced its own share of problems, most notably having been torn apart by the divisive Vietnam War. Many other issues—racism, urban life, generational struggles—triggered an unprecedented era of soul-searching. Even athletes, once regarded simply as loyal and apolitical, began to behave very differently. Starting in the mid-’60s, boxer Muhammad Ali, basketball star Bill Russell, baseball player Curt Flood, and tennis stars Arthur Ashe and Billie Jean King were among those who raised questions about the relationship between the athlete and society.

While Ashe and King spoke about social issues beyond the lines, they also were among the many people in tennis who’d started to redesign the structure of the sport itself. The arrival of Open tennis in 1968 began the toppling of the static autocracy and marked the dawn of a dynamic market economy, the sport increasingly fueled by prize money, corporate sponsorship, attendance, television ratings. Players, long under the thumb of such national organizations as the USLTA, were starting to assert themselves as they never had. One month prior to the Davis Cup finals in Bucharest, the men formed a players’ association, the ATP.

Then there was an even more close-at-hand factor that loomed over Bucharest: the threat of terrorism. The previous month, at the Summer Olympics in Munich, 11 members of the Israeli team were taken hostage and killed by members of the Palestinian group Black September. With Davis Cup the next big event on the international sports calendar, and two Jews on the U.S. team (Harold Solomon and Brian Gottfried), rumors surfaced that Black September would strike in Bucharest. Ceausescu ordered a complete lockdown for the American squad, arranging for it to be sequestered on the 17th floor of the Intercontinental Hotel, guarded by a phalanx of security guards and whisked through the streets in armored cars. ABC TV correspondent Peter Jennings, who’d covered the tragedy in Munich, arrived in Bucharest. His presence was a reminder that the news wasn’t necessarily going to highlight forehands and backhands. Jennings signified another possibility: slaughter.

***

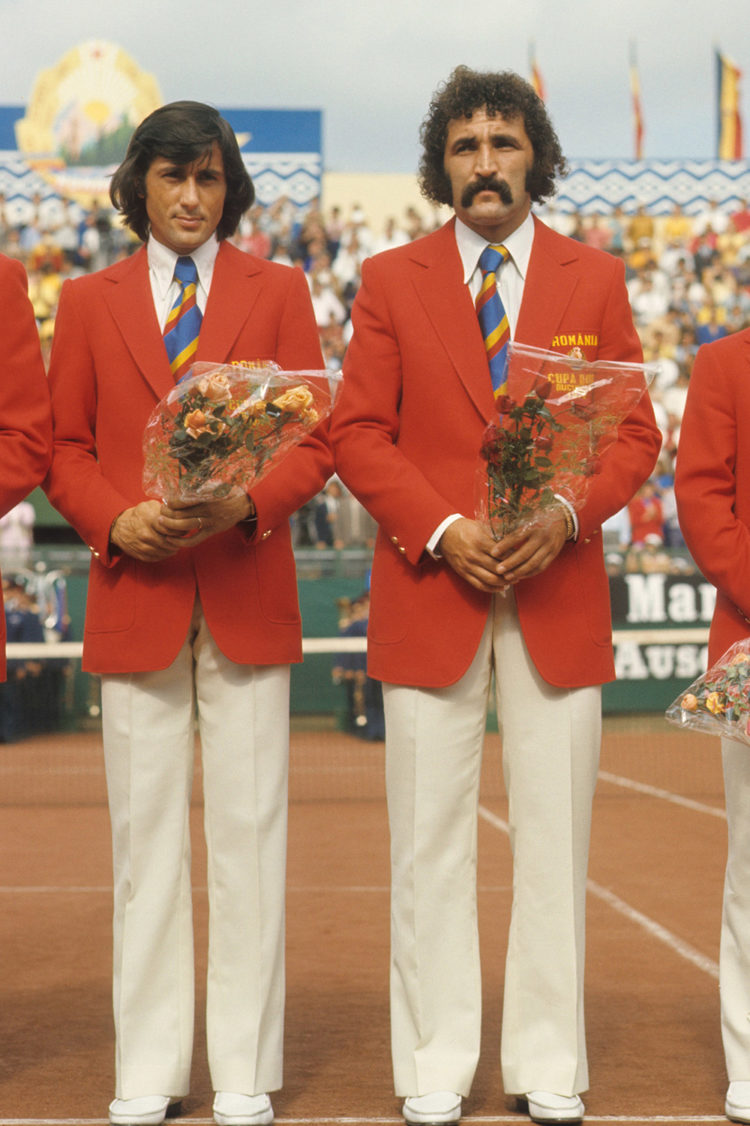

On the surface, the only thing Smith and Tiriac appeared to have in common was that each of their faces was adorned by a late-’60s fashion statement that by the early ’70s had become fairly common: a mustache. While Smith’s was as neatly trimmed as his blond locks, Tiriac wore a sprawling Fu Manchu, a fitting companion to a head adorned with thick, curly black hair and a deliberately mysterious persona. The Tiriac mustache, wrote John McPhee in Playboy, “somehow suggests that this man has been to places most people do not imagine exist.”

A deeper look revealed that Smith and Tiriac were each superb competitors, men who shared the payoff from tennis that’s available for those skilled enough to win at the highest levels. Tennis for world-class players was a passport, an enjoyable way to travel the world and create opportunities. A major difference, though, was that for Smith, the passport metaphor was figurative. For Tiriac, it was literal. As he would tell journalist Peter Bodo more than 30 years after this match, “For me and others like me [other Eastern Europeans who lived under the communist thumb], tennis was water in the desert. In my time, 99.9 percent of the people in my part of the world did not have the same privilege as I, to travel, to be an athlete, to see the world, to come home again. Tennis made me free.”

Born in 1939, less than four months before the start of World War II, Tiriac grew up in Brasov, a town roughly 90 miles north of Bucharest located in Transylvania, the province known as the home of Count Dracula. In the wake of a war that saw his homeland join forces with the Nazis, invaded by Russians, overtaken by Communists, Tiriac witnessed how rules were eminently malleable. Harsh pragmatism became personal when Tiriac’s father died the year Ion turned 11. His mother worked at a factory. While also employed at a truck factory, Tiriac became skilled at table tennis and hockey. In the latter, Tiriac played for Romania’s 1964 Olympic team.

Tennis didn’t seriously enter the picture until Tiriac was 17, a late age to become a world-class player. But by the early ’60s, Tiriac was the best player in unsung Romania and started to compete successfully on the international circuit.

Tiriac described himself as “the best player who can’t play.” His strokes were what you’d expect from someone who’d taught himself the game in a nation with a negligible tennis culture—an awkward shovel of a forehand, reasonable backhand, moderate serve, plausible volleys. But the Tiriac mind was extraordinarily devious. His late start and a dearth of instructional knowledge had made it difficult to master technique. The study of tactics, though, was a field where Tiriac earned a doctorate. “Tiriac was a very clever player, very unorthodox,” said Gorman. “He was very good at analyzing strengths and weaknesses. He’d play against his opponent.”

As you’d expect from someone who occupied an autocracy laden with corruption, Tiriac was extremely adept at bending rules. Compared to Iron Curtain bureaucrats, tennis officials were child’s play. In this pre-Open era, players rarely if ever engaged in gamesmanship. That honor code meant nothing to Tiriac, who intimidated linesmen, haggled with chair umpires, bumped into opponents on changeovers, even belittled them.

Off the court, though, Tiriac could be amicable with his fellow competitors. Besides “Count Dracula,” his other nickname was “Tiri Baby.” A photo from the ’60s shows him at a charity event, performing the Dance of Seven Veils in briefs and bare feet. Tiriac savored the chance to stand out in all sorts of ways, be it greeting people with head butts, excessive dining habits—one year in Milan his breakfast included a dozen eggs, six steaks, and four bowls of pasta—or even the occasional consumption of a champagne glass.

***

While Tiriac, who wore the Count Dracula nickname without complaint, was the Prince of Darkness, Stan Smith personified sunshine at the zenith of the American Century. His father, Ken, was an Eagle Scout originally from a Nebraska town named for a revered American president—Lincoln. Mr. Smith came west to Pasadena, a suburb of Los Angeles that was as wholesome as you can imagine, and worked as a community college sports coach before commencing a career in real estate.

Stan, born just after the war in 1946, took rapidly to sports. He began to play tennis at the age of 11. One of Smith’s teachers was former world No. 1 Pancho Segura, who concurrently helped Ashe, then at UCLA. Smith also received extensive instruction from George Toley, head coach at the University of Southern California (USC), which along with crosstown rival UCLA was one of college tennis’ two superpowers. Both teams were so good that such Bruins as Ashe and Trojans like Ralston competed in Davis Cup while still enrolled as undergraduates.

By the time Smith was 17, he became the best junior in America and of course headed to USC. In 1967, Smith won the NCAA singles and doubles title with his most frequent partner, Bob Lutz. The next year, Smith and Lutz defended that title, won the US Open, and together scored the clinching point for the U.S. in the Davis Cup Challenge Round.

There was an aura of destiny around Smith, an awareness throughout the tennis world that everything from his Southern California tennis pedigree to USC, Davis Cup, and beyond were logical rungs up the ladder for this serve-volley manifestation of Captain America. Smith even served in the Army, rising to the rank of corporal.

A major step forward came in 1971, when Smith reached the finals of Wimbledon, leading defending champion John Newcombe two sets to one before losing 6–4 in the fifth. Later that summer, Smith won the US Open, scored the winning point for the victorious American Davis Cup, and finished the year ranked No. 2 in the world. In July 1972, he won the Wimbledon singles title.

Perhaps the only person playing better tennis than Smith in 1972 was the man he’d beaten in that Wimbledon final and would face in the opening match of the Davis Cup finals.

While Tiriac represented one jarring contrast in breeding and manner to Smith, Nastase posed yet another. Long before Roger Federer, before the emergence of John McEnroe, near the end of Rod Laver’s career, tennis’ most sizzling talent took the form of a man with a perfect tennis body and a flawed tennis brain.

Born the same year as Smith, Nastase, the son of a security guard, grew up across the street from the Progresul Club, Bucharest’s sprawling sports facility. Like many European boys, Nastase first played soccer, but soon found himself drawn to tennis, enamored with the sport’s singular qualities.

Unlike Tiriac, for whom everything in tennis was labored, Nastase was a natural. Akin to Laver, McEnroe, and Federer, he was one of those players of whom it was said, he could make the ball talk. Nastase had remarkable vision, quickness, reflexes. Others moved and lined up to hit the ball in a linear manner. Nastase darted and flicked, his game possessed of a lightning-like ability to snap off bold forehands and backhands, touch volleys, and deliver deceptively wicked serves. “I know I lucky to grow up with sounds of balls hitting rackets,” said Nastase in a 1972 Sports Illustrated profile authored by Curry Kirkpatrick, “smell of freshly sprinkled courts at four in the morning, I learn everything by looking[DS5] .” His body grew into a supple 6′ 0″ tall, 165 pounds.

It figured that Nastase loved wielding the Dunlop Maxply Fort, an elegantly designed, light frame also used by such flashy shot-makers as Rod Laver and Lew Hoad. The Maxply resembled a flyswatter as it whipped all over the ball to impart topspin, aided by the Continental grip Nastase favored. Few things pleased Nastase more than the chance to surprise his opponents.

In contrast, Smith personified discipline. His racquet was classic America; straight from Illinois, the Wilson Stan Smith Autograph, a heavier frame that rewarded sustained leverage. In Smith’s case, that also meant using an Eastern grip, a technique such Americans as Don Budge, Jack Kramer, and Tony Trabert believed carried far more heft and reliability than the Continental grip that they often deemed, in Budge’s words, “flimsy.”

At the age of 13, Nastase ball-boyed for Tiriac, and soon became his protégé. Tiriac knew his own chances for greatness were limited. But he instantly saw that this tennis savant had the goods to go much further. And that success in turn could provide both of them with yet more leverage, autonomy, and money. In 1966, Tiriac and the 19-year-old Nastase made a surprising run to the finals of the doubles at Roland-Garros. Though handily beaten by Ralston and Clark Graebner, the effort was worthy of a celebration. That evening, Tiriac provided Nastase with the gift of an evening with a woman. As Nastase years later wrote in his autobiography, “So that’s how I got laid the first time…. I was so shy, having problems even getting physically close enough to look her in the eye.”

Attaining feminine companionship rapidly ceased to be a problem for Nastase. He made himself a presence in the festive and competitive tennis world. Photos show Nastase and Tiriac in the common garb often given to top European players—crisp white Fred Perry shirts and shorts, paired with the sculpted Maxply, encased in its shiny maroon racquet cover. This was lush life in the West, a striking contrast to Iron Curtain austerity. So long as Nastase and Tiriac fared well in Davis Cup and brought prestige to Romania, they were shielded from most forms of government subjugation. In the 1972 article “The Hotdog and Dracula at Home,” Bud Collins described a Romanian win over Italy as “Davis Cup European-style: a boisterous, joyous celebration of an involved crowd. Nationalistic but more fun than the tomb-side protocol of Forest Hills or Wimbledon allows.” Tennis in Romania boomed from 2,000 players in the early ’60s to 25,000 a decade later.

Nastase’s Achilles heel was that the joy he took in hitting tennis balls could also curdle. There were times he would lose focus and get into squabbles with officials—lengthy arguments that often cost him matches. Said Tiriac, “He doesn’t have a brain, he has a bird flying around inside his head.” Nastase also freely gave the bird to linesmen and spectators. Far more upsetting to Nastase’s peers was that the delays often derailed their momentum. Nastase even mocked his rivals mid-match, a form of rudeness not previously seen in tennis. At the 1972 US Open, having been beaten by Nastase in the finals, Arthur Ashe acknowledged the victor’s tennis skills and added, “When Nastase brushes up on his manners, he’ll be an even better player.”

***

As the competition neared, each team prepared, in its own way. The American team arrived in Bucharest 10 days before day one of competition. They’d previously spent several days in Paris, playing simulated Davis Cup-like matches on the clay of Roland-Garros versus various French players. Landing in Bucharest, the Americans were whisked to the Intercontinental by a team of 20 security guards, clad in leather jackets and armed with machine guns and knives. There would be no stops for red lights in the government vehicles that sped them to and from practices, no day trips to parks or museums, no exotic dinners, no flirtations with lovely locals.

But while the American team’s yearlong spirit of collegiality likely increased amid its cloistered conditions, rancor infected the Romanian squad. Similar to the many tennis players now liberating themselves from their national associations, Nastase had begun to bridle under Tiriac. In 1971, Nastase won eight tournaments, reached the finals at Roland-Garros, and earned more than $100,000 in prize money. The sex-starved teenager was now 25 years old and had the world at his fingertips, tennis’ incarnation of football star Joe Namath. Who needed the bossy Tiriac?

For most of 1972, Nastase and Tiriac hardly spoke to each other. At the US Open, Nastase ditched Tiriac as his doubles partner. After the US Open ended in mid-September, Tiriac returned to Bucharest and began to train for Davis Cup. Nastase went west for hard-court tournaments on the West Coast. Only in late September did he return to Europe, starting with a week off in Brussels, where Nastase enjoyed time with his fiancée, Dominique, and didn’t touch a racquet. Finally, on the Monday prior to the Friday start of Davis Cup, Nastase surfaced in Bucharest, greeted by an angry Tiriac.

“So I started to practice hard, several hours a day,” wrote Nastase, “and, because I’ve got quite soft hands, I got this enormous blister, all over the palm of my hand, all open.” Added to the blisters was that a Communist Party official decided it would be best for Nastase and Tiriac to also spend the week in a hotel. Most frustrating for the highly libidinous Nastase was that Dominique was forced to stay elsewhere. “What annoyed me most,” wrote Nastase, “was that Ion said nothing, because if we had both refused to cooperate they would have had to abandon the plan.”

Taking a break from all these restrictions, Nastase on Wednesday night headed to the airport. He loved to zip around the streets of Bucharest in his Ford Capri. On this occasion, he arrived to personally whisk a group of British and American journalists through customs. He was, after all, a lieutenant in the Romanian army, an even higher rank than Smith. To hell with Tiriac. Besides, there was no way Smith could beat him on clay.

Guarded by a full troupe of machine-gun-armed protectors, the American team remained extraordinarily focused. Thursday, the day before the matches, Ralston made one of the toughest decisions he’d ever make as Davis Cup captain. Solomon had won three of four matches on the clay in Chile and Spain, including two five-setters. His attrition-based baseline game was a perfect fit for epic matches on the dirt. But following the US Open, Solomon returned to college, to start his junior year at Rice University.

What happened when Solomon rejoined the team remains a matter of debate. Gorman was certain Solomon would be the second singles player alongside Smith. But Ralston and Smith believed Solomon was out of shape. Added to the picture was that Solomon was Jewish. Given the rumors of Black September activity, were he on the court, something horrible could happen. Would that possibility make Solomon edgy? Ralston selected Gorman. Solomon was angry. He’d won prior matches in challenging conditions. “Plus, everybody knew,” Solomon said, “if [Tiriac] played me, he was going to be out there—even if he beat me he was going to be out there for five hours, you know what I mean?” Were Tiriac to play Solomon, he would emerge far more depleted than versus the net-rushing Gorman.

That day Ralston also met with the Romanians, including the team’s captain, Stefan Georgescu. Typically, this meeting was cordial and perfunctory. The leaders would clarify a few basic rules and wish each other well. But in this case, Romania issued a remarkable demand. Usually in tennis, balls are changed after the first seven games and every nine thereafter (the warm-up the equivalent of two). Romania’s opening recommendation: Change after the first 27 and every 29 games; naturally, all the better to aid the home team on the clay. An outraged Ralston countered: How ’bout we change at one and three? As Ralston recalled, “They said they didn’t have enough balls. Unbelievable. Finally, we settled on seven and nine, just like Wimbledon.”

So unquestionably, even before a point was played, a spirit of danger and corruption threatened to overwhelm Davis Cup’s longstanding tenets of competition and camaraderie. Back in September, upon learning his squad was headed to Romania, Ralston spoke with Australian captain Neale Fraser, whose squad had recently lost there. Fraser addressed Ralston in a manner similar to that of a battle-scarred French general warning his American counterpart about the hellacious jungles of Vietnam. No matter what you do, said Fraser, you can’t win. They won’t let you. They’ll cheat you blind.

The American Davis Cup team was all about sportsmanship. No one more than Smith personified the “Silent Majority” Nixon had referred to as the tumultuous ’60s drew to a close—patriotic Americans who kept their hair short, served in the military, believed in God, did not experiment with drugs or protest on college campuses. Nixon, Smith, and Ralston, a trio of dutiful Southern California natives, each believed obedience and honor were the American way. Of course, they also happened to be citizens of a democracy, where it was always possible to come and go as one pleased.

Life was quite different on the fortress-like 17th floor of the Hotel Intercontinental American team rode a private elevator, was watched by security cameras, and was barred from walking too close to windows[DS9] . Finding precisely what he needed for this bizarre situation, Ralston toggled between faith and adventure, spending his leisure time reading the Bible and James Bond books. Gorman and Smith’s doubles partner, Erik van Dillen, prepared their version of The Tonight Show, a skit performed at team dinners that starred van Dillen as the witty Johnny Carson and Gorman as his cohost, the avuncular Ed McMahon. Thursday night, van Dillen gave Colwell the “Oscar Meyer Wiener Award” for giving away the choice of grounds. They didn’t realize Colwell was in the room. Thankfully, Colwell took it in good stride.

While the underdog American team relaxed, Romania marched in different directions. Tiriac concocted his plan for beating Gorman in the opening day’s second singles match. Nastase seethed, miffed at being denied Dominique. “Though I did once manage to sneak her into the hotel,” wrote Nastase, “under pain of immediate execution, so that we could have sex, because I was going out of my mind with tension by then.”

***

In the three years leading up to this match, Smith and Nastase had played each other 12 times, Smith winning seven. In 1969, in his US Open debut, Nastase kicked off the rivalry with a second-round upset of the 12th-seeded Smith. Their most recent match happened at Wimbledon in July ’72. It was one of the finest Wimbledon finals in history, an up-and-down nail-biter. In the fifth set, Smith served at 4–4, love–30. Nastase lashed with his Maxply, rifling a forehand crosscourt passing shot. Smith lunged, sticking out his thick Wilson frame to stab a frame forehand volley that barely dropped over the net for a winner. Smith held. Serving at 5–6, Nastase lost the match by netting an easy high backhand volley.

The Progresul Club had tripled the number of seats in the stadium, from 2,400 to 7,200. “Nastase should beat Smith on the clay,” Ralston said Thursday night, “but if Stan wins the first match it’s extra cake for us. It’ll be all over.”

Beyond possessing powerful volleys and one of the best serves in the game, Smith also owned an intangible quality that proved critical in every match he would play over the next three days. “There was one thing above all else you had to make sure to do when you played Nastase,” said Gottfried. “You had to keep your head down and not pay attention to anything he did, whether it was a great shot, an argument with the officials, or something else with the crowd.” Some players didn’t like being shown up by Nastase and, in their efforts to engage in all sorts of one-upmanship with the brash Romanian, often unraveled. But Smith’s ability to detach was unsurpassed. For a tall blond WASP who represented so much of America’s Nixon-era rigidity, Smith’s serenity was downright Zen, far more subdued Big Sur than rah-rah USC.

Smith served for the first set at 5–3. Nastase broke back, the crowd screaming “Na-sta-se!” increasingly louder after each winning point. At 8–8, he again captured Smith’s serve and prepared to take a critical early lead. But on the first point of the next game, Nastase double-faulted and became unglued. He missed an easy volley to drop serve, double-faulted twice when serving at 9–10. Down set point, the Romanian was caught off guard when Smith closed out the set with a shot straight out of Nastase’s playbook—a lob volley. A relaxed Smith found a higher gear. He relentlessly attacked Nastase’s weaker backhand and suspect second serve to take the next two sets handily, 6–2, 6–3. The allegedly uptight craftsman had easily disposed of the frequently carefree artist. Nastase exited the stadium to the loudest boos he’d ever hear in Romania. Now it was time for the match America expected to win, Gorman versus Tiriac.

Nimble and affable, Gorman was raised in Seattle, the son of a medical administrator. His childhood dream was to play second base for the New York Yankees. By age 12, Gorman saw that his peers were getting much bigger and decided to put more energy into tennis. Since it rains 300 days a year in Seattle and the indoor tennis club boom hadn’t happened yet, Gorman hustled hard for court time, taking two buses to get to the prestigious Seattle Tennis Club. By his last year in the juniors, Gorman was ranked 31st in the country, hardly worthy of USC or UCLA. Instead, he became the star player at little-known Seattle University.

After graduating in 1968, thinking he’d soon be a stockbroker, Gorman decided to give pro tennis a shot and later that year headed to Australia. Gorman’s[DS10] swiftness when moving forward to volley, combined with a lively kick serve, strong work ethic, and composed temperament, all helped him improve rapidly. By 1970, Gorman was ranked sixth in America.

As much as it’s possible to view tennis through the American team’s lens of values and character, even by those standards, what Gorman did several weeks after Bucharest remains an amazing moment. He’d qualified for the first time to play the year-end Commercial Union Masters event, held in ’72 in Barcelona. In the semis, a best-of-five match, Gorman played Smith. At some stage, Gorman felt a twinge in his back, a longstanding intermittent injury. The pain was so familiar, Gorman knew he’d be unable to play the next day, but also figured Smith would beat him anyway. Instead, resigned and relaxed, Gorman played great tennis to go up two sets to one. In the fourth set, he crushed a sweet backhand to arrive at match point—and immediately told the referee, “I can’t go on. My back is killing me.” The paying customers would have a proper final. Alas, the values Gorman had internalized would prove of no use in the face of what Tiriac was about to do to him.

Two sets in, Ralston’s decision to go with Gorman over Solomon looked good. Gorman always felt comfortable competing versus Tiriac. He rapidly won the first two sets 6–4, 6–2, and went up a break in the third.

Watching in the stands, Gottfried thought this was fantastic, that America would win both singles matches, ride the wave of momentum through the next day’s doubles, and wrap it all up Saturday.

Tiriac had other ideas; lots and lots, or maybe just one: win the match by any means necessary. Tiriac began to take excessive time in between points. He started to make scarcely subtle signals to linesmen to demand a point be replayed; or even, to reverse line calls. What started as a trickle of chicanery became a flood. Tiriac snatched the third set, 6–4.

The ILTF dispatched a referee from a neutral nation to oversee Davis Cup matches. The referee in Bucharest was Enrique Morea, a respected Argentine who’d been a top 10 player in the ’50s. As Tiriac’s antics accelerated, Morea attempted to intervene with the chair umpire. Since the chair umpire barely understood English, an interpreter was required. That became Tiriac. Between points, Tiriac sat on a linesman’s chair, often delayed the start of points by up to 15 minutes, and incited the crowd, already frenzied, to yell even louder. Morea begged Tiriac to stop but grew helpless, even when physically pushed by Tiriac.

This wasn’t the genteel, self-governed world of pre-Open tennis. Nor was it the blossoming commercialized world of professional tennis. It was all about Tiriac, who with each passing point put a stranglehold on everything. The tennis strategy was straight out of Tilden: Let your racquet undo your opponent. But Tiriac added another layer, applying a Romanian proverb he relished sharing: Better your mother cry than my mother cry.

Gorman, wrote Bud Collins, “was certain that a Balkan coughing conspiracy was unfolding, that spectators were following instructions to clear their throats and jar the silence and his concentration whenever he served.”

“It all started to wear on me,” said Gorman. “I was in such a fog. I had to hit the ball so much inside the lines to win a point. At least 10 times, we’d have to replay a point, always when it was a game point for me.”

Ralston was furious. Everything he’d learned about fair play was being obliterated by Tiriac. In the fourth set, Gorman got yet another horrendous call. Tiriac was on Ralston’s side of the court. As the Romanian walked to change sides, Ralston blew up. “Tiriac comes about two feet from me,” Ralston recalled. “I called him every name in the book—SOB, cheater, all of it. I was holding one of Tom’s racquets, that fiberglass Head Competition. If Tiriac had made one move to me, I was ready to hit him with the racquet. I would have killed him, and maybe we’d have all been dead. But he just gave me that shrug and kept going.”

It only got worse. Tiriac took the fourth, 6–3, and ran through the fifth, 6–2. A large white towel was thrown over Tiriac’s head as he left the court to loud cheers.

“TI-RI-AC! TI-RI-AC! TI-RI-AC!”

Gorman didn’t need a racquet, quipped Collins. He needed a cross.

“It was the lowest night of my tennis life,” said Gorman. His teammates were outraged. In came Morea. Ralston and van Dillen begged him to take disciplinary action. Sorry, boys, it’s not so easy, said Morea, who revealed that he’d received death threats. Van Dillen said it would be better to leave immediately. Let them have it, he said, they’re nothing but a bunch of cheaters. That option was ruled out. It was time to focus on Saturday’s doubles, an occasion that filled van Dillen with dread.

A year earlier, in Charlotte, Tiriac and Nastase beat Smith and van Dillen 7–5, 6–4, 8–6. Van Dillen had not played well. The twin challenge of representing his country for the first time and dealing with the gamesmanship often employed by the Romanians was a stressful combination even someone as experienced as van Dillen had never faced.

And make no mistake, Erik van Dillen had waged many battles. While Smith and Gorman were late bloomers, van Dillen was a prodigy. As a junior, he won national titles in every age group, headed off to USC in the fall of 1969, and turned pro after his freshman year. In 1971, due to various political machinations within the tennis world, Smith was forced to abandon his longstanding doubles partnership with Lutz. Ralston and Toley thought van Dillen would be a perfect replacement. At the ’71 US Open, just prior to the match in Charlotte, van Dillen and Smith reached the finals. They also made it that far at Wimbledon the next summer.

Like all of the Americans, van Dillen’s behavior was exemplary. He grew up in San Mateo, a suburb south of San Francisco, in a lower-middle-class household, his widowed mother working as a secretary. Peninsula Tennis Club in nearby Burlingame was the focal point of his tennis education, van Dillen absorbing the sport’s values communally. “If I hit my racquet on the ground or said a swear word, five parents would be there to discipline me,” he said. “You learned what the game was, to always close the gate, pick up the balls, look people in the eye, and shake their hand.” Like Gorman, van Dillen often rode buses to compete, his entry fees paid for with money he earned giving lessons.

Friday night, van Dillen went to sleep at 10. At least, he tried. Then van Dillen remembered something he’d been told by Pancho Gonzales: Sleep was overrated when you were a young, fit athlete. The biggest mistake people make is to try to sleep and then spend the whole night tossing and turning. Take a walk. Escape. Breathe.

Unfortunately, in this situation, all van Dillen could do was pace up and down the halls of the Intercontinental.

Sometime after midnight, van Dillen heard a voice.

“Hey, kid—can’t sleep?”

It was Jack Kramer. Kramer was tennis’ version of LeBron James and NBA commissioner Adam Silver. He was the world’s best amateur in 1947 and No. 1 pro from ’48 to ’54. Kramer had also been head honcho of the pro barnstorming tour for 15 years and recently agreed to be the executive director of the newly formed ATP.

“I’m struggling,” said van Dillen.

“Join us.” Kramer was sitting with Donald Dell, a prior Davis Cup captain who had become tennis’ first agent, Ashe and Smith his two most notable clients (as were van Dillen, Gorman, and Ralston).

With exceptional politeness, Kramer said, do you mind if I give you some advice? Kramer added that he knew that giving advice to someone at this stage could also be unhelpful. So do you mind?

Sure, said van Dillen, figuring he’d next hear a tip about his service motion or toss.

Kramer revisited the match in Charlotte, telling van Dillen that he’d played well enough to lose. On the eve of the next day’s match, Smith (and everyone else) was worried about how van Dillen would fare in much tougher conditions. This was untenable, said Kramer. You’ve got to let Stan be Stan. So the minute you go out there, you’ve got to go for winners. You’ve got to send a message to Stan, Nastase, and Tiriac that you are going to be a different person.

Everything suddenly became much clearer for van Dillen. He was no longer worried.

***

Prior to Saturday’s doubles match, both teams gathered for a ceremony. As the squads walked to their places, Gorman felt a tap on his shoulder. It was Tiriac.

Tom, said Tiriac, I want you to know something. What happened yesterday wasn’t personal. I was just doing what I had to do.

***

Romania’s momentum continued as the doubles began. Van Dillen was aware that if he didn’t stand nearly a foot behind the baseline to serve, he would be called for a foot fault. Adjusting, van Dillen lost serve in the first game. The crowd exploded so loudly that Gorman compared it to a massive earthquake.

Then everything changed. Smith and van Dillen had decided they were going to frequently return down the line. Nastase’s quickness made him a superb poacher. But he wasn’t nearly as proficient a volleyer from a standing position. With the Romanians serving at 2–1 in the opening set, van Dillen hit a forehand down-the-line winner and then another off his backhand to break back at love. When Smith served, and on other occasions, too, van Dillen became a highly aggressive poacher, thundering one volley winner after another. The Romanians disintegrated. Five games into the match, as the teams changed sides, Nastase ceased waiting for Tiriac. The Americans stormed through the first two sets, 6–2, 6–0, and went up 5–3 in the third, Smith serving to close it out.

As van Dillen recalled, that game seemed to last 100 years. Nastase and Tiriac were tremendous lobbers, but had hardly done so until this 5–3 game. Most of the lobs went van Dillen’s way.

At last, Smith and van Dillen reached match point at 40–30. Smith turned to van Dillen and said his plan was to roll in a smooth spin serve and seek to take control of the court.

No way, said van Dillen. You have the best serve in tennis, he told Smith. Hit it big and let’s end this thing once and for all[DS15] .

Smith launched his serve down the center. Tiriac, proficient with that shovel forehand, struck a fine return. Smith hit a half volley that trickled around the net twice—and at last dropped over for a winner. Total time for the match: 68 minutes.

In two days, Nastase had failed to win a set. “If I ever wanted to dig a hole and disappear from view a match,” he wrote, “this was probably it.” Nastase’s only chance to dig out of it was in Tiriac’s hands.

***

At the Intercontinental, the prior night’s emotions were ancient history. The situation was clear. From Jamaica to Mexico, Chile to Spain to Bucharest, the whole year boiled down to Sunday, starting with Smith versus Tiriac. But while all were shocked by what happened to Gorman on Friday, everyone now knew what was in store.

Sunday morning, Morea told Smith it would be great if he could win the match quickly. Otherwise, things might really get out of control.

Gorman and van Dillen went to a remote court to practice. Solomon ran back and forth with score updates.

Tiriac won the first set, 6–4. Just the threat of what shenanigans he might pull was toxic.

But this was Stan Smith. Less than a decade prior, at a Davis Cup match played at the Los Angeles Tennis Club, Smith applied to be a ball boy and was told he was too clumsy for the job. This hurt, but didn’t faze. Smith trained hard, be it in sessions with Toley, by himself with his serve or a jump rope, in hour after hour of practice matches, following his delivery to the net again and again and again, dispatching passing shots and lobs, cracking returns and passing shots through narrow openings.

Smith’s summer of 1972 had started at Wimbledon, where he barely squeaked by Nastase on tennis’ most elegant and sacred court. Now, on this gray fall day behind the Iron Curtain, thousands of miles from home, in an arena filled with corrupt officials, in a stadium lined by machine guns, amid the sounds of a fiercely partisan crowd, on his most challenging playing surface, Smith was in a street fight, once again versus a Romanian, this one far less talented, but extraordinarily cunning.

Tiriac employed many of his trademark rope-a-dope tactics—high, low, short, angled shots, mixed with attack. The crowd got louder and louder. Bad line calls. Delays. In the third set, when Smith received a rare good call, an American in the crowd yelled out, “It’s about bloody time.” Spotting this man, Tiriac motioned to the security guards. The American vanished under the stands.

Smith won the next two sets, 6–2, 6–4. But Tiriac fought back in the fourth. By this time, even Smith grew flustered. He faked swings at Tiriac, made rude gestures.

With more than 7,000 Romanians screaming for blood, Tiriac was the law. At one point, Morea threatened to default Tiriac. Go ahead, said Tiriac. See what happens. This too might have been fodder for Peter Jennings.

And so there they were, Ralston on the sidelines, Gottfried, Solomon, and fellow hitting partner Eddie Dibbs nearby, van Dillen and Gorman in the locker room, no more than 100 Americans in the stands. Smith was the sheriff, headed for the shoot-out like Gary Cooper in the movie High Noon.

Smith worried that no matter how well he played, he would not be allowed to win. Though a cross sure helped, to kill a vampire, you had to drive the stake through his heart. Smith knew he needed to do two of the most difficult things in tennis: hit winners, and aim them far enough inside the lines so that there was no way they could be called out.

Tiriac knew the score too, was aware that this win could mean so much, certainly for Romania, but more pointedly, for him and even for that birdbrained Nastase, who this weekend had proven absolutely worthless. Didn’t Nastase understand that victories were the best way to keep the government off your back? This would be the 33-year-old Tiriac’s 13th set in three days—versus a man seven years younger who also happened to be the best player in the world. But in both of his singles matches thus far, Tiriac was a master of the intangibles, a rebel aware of all it took to topple the American empire.

Ralston felt his stomach knotting. He’d held the racquet during Davis Cup losses in Cleveland, Spain, and Brazil. Now Ralston could only watch further American agony. But he covered up his fears, all in the service of Smith, the man with whom he’d shared so much—those endlessly sunny Southern California days, those slick hard courts where they’d each mastered serve-and-volley tennis, the Los Angeles Tennis Club, USC; and at this moment, the need to overcome evil.

Smith served to start the fifth. Accounts vary about how those opening points went, whether Smith was down love–40 or 15–40 or held easily. But all present agree on one point: Smith fired an ace down the T in the deuce court. Upon seeing that, van Dillen turned to Gorman, the two now in the locker room, and said, “It’s over. Stan’s going to win.” Smith held that first game and then commenced a march that soon became a sprint. Tiriac had sunk his teeth into Gorman’s neck and attempted the same with Smith. But Smith was not about to give any blood to Tiriac’s cause. Over the course of six games, Smith hit 18 winners. Tiriac won eight points. At 0–5, 15–40, Tiriac lurched his way to net and was passed cleanly by a Smith down-the-line backhand.

As Smith’s lead grew, he pondered how he would interact with Tiriac once the match was over. A fist? Too confrontational. Walk away? Not confrontational enough. Smith even wondered if Tiriac expected to be praised for his valiant effort.

As they shook hands, Smith said, “I don’t respect you as a person anymore.”

With that, Smith reached out with his left hand, patted Tiriac on his right shoulder, and swiftly turned to his right.

A stunned Tiriac raised his right hand, as if he hoped to talk further with Smith. But Smith, already several feet away from Tiriac, headed for a hug with Ralston and others.

Tiriac stood alone.

Gorman and Nastase played the final, meaningless match. Nastase’s four-set victory did nothing to overcome his failures. “If Nastase ever wants to know what went wrong in this embarrassing weekend for Romanian tennis,” wrote Curry Kirkpatrick in Sports Illustrated, “he need only ask himself.”

That same day, the police found two people trying to scale the walls of the stadium. No one knew if they were terrorists, but Ralston was told they were “disappeared” by the authorities.

A complete turnaround marked the awards ceremony. Upset as Tiriac likely was by Nastase’s preparation and performance, he praised his partner at length, reminding all present that the credit for Romania reaching the finals for a third time was largely due to Nastase. Then the crowd, hostile to the American team for three days, began to applaud the victors, quietly at first, but eventually, loudly. Wrote Smith years later, “I was surprised and moved. It was something I never expected.”

Jubilation from the Americans? More like relief. Sunday night they packed. Monday morning’s flight home was scheduled for 9 a.m. But a call came. Ceausescu wanted to meet with both teams Monday morning. The flight’s departure would be delayed for several hours. “Can you imagine Nixon calling American Airlines and doing that?” asked Ralston.

***

Through the first half of 1973, Smith and Nastase remained the two best players in the world. Since the fractured nature of pro tennis led each to compete on different circuits, not once during that time did they play each other. Smith was the leading player on the WCT tour, winning seven titles, the last at WCT’s prestigious season-ender, held in Dallas each May. Nastase began the year with three victories at U.S. indoor events, then seamlessly transitioned to the European clay circuit and won six tournaments, including Roland-Garros. Just before Wimbledon, Nastase won a grass-court event in London. It seemed reasonable that he and Smith would meet again on Centre Court.

But the ATP’s tussle with the ILTF and, subsequently, Wimbledon altered the arc of each of their careers. Smith joined forces with his fellow members and refused to play. Nastase, invoking government demands, declined to boycott. Seeded one at Wimbledon, a heavy favorite to win the championship, Nastase lost in the fourth round to recent NCAA singles champion Sandy Mayer. He also surrendered his US Open title earlier than expected. Save for a run to the Wimbledon finals in ’76 and a semifinal effort at the US Open that same year, Nastase never again was a significant factor at any of the majors.

Nastase was inducted into the International Tennis Hall of Fame in 1991 and unsuccessfully ran for mayor of Bucharest in 1996. In 2012, Nastase was elected to the Romanian Senate. Five years later, as Romanian Fed Cup captain in a tie versus Great Britain, Nastase made racially insensitive comments about Serena Williams’ unborn child, harassed British captain Anne Keothavong, harangued British player Johanna Konta, and during a match was ejected from the stadium due to unsportsmanlike conduct. Subsequently, Nastase was investigated by the ITF, fined $10,000, and suspended from acting in an official capacity at any ITF team events until 2021. As for Dominique, the two divorced after 10 years together. In 2020, Nastase got married for the fifth time.

Two frustrating matches hindered Smith. At the 1973 US Open, he was seeded first, but lost in the semifinals to Jan Kodes after holding a match point. The next year, in the final four of Wimbledon, Smith led Ken Rosewall two sets to love, held match point in the third-set tiebreaker—and lost that one, too. Wimbledon ’74 proved the last time Smith reached a Grand Slam singles semi. Arm injuries also plagued him during these years. Smith remained a Davis Cup stalwart, reuniting with Lutz to win several doubles matches during American title runs in ’78, ’79, and ’81. In 1974, Smith married Princeton tennis star Marjory Gengler. The two had four children, all of whom played college tennis. Inducted into the International Tennis Hall of Fame in 1987, Smith became president of the ITHF in 2011.

Having played each other 14 times between ’69 and ’72, Smith and Nastase met only seven more times in the next decade—and never at a major or live Davis Cup match. The final head-to-head: Smith 11–10.

Oddly enough, as conventional as Smith’s life was, it was he, not the flamboyant Nastase, who enjoyed enduring crossover commercial success. The adidas shoe that bears Smith’s name was first introduced in 1972 and in time gained a worldwide cult following. Notables who’ve worn it include David Bowie, John Lennon, and Jay-Z; the latter even mentioned the shoes in a song he wrote. More than 50 million pairs have been sold. Smith once estimated that 95 percent of the people who’ve bought them have no idea if the name “Stan Smith” even stands for a real person.

The Svengali-like approach Tiriac first took with Nastase proved viable. As his own playing career wound down in the mid-’70s, Tiriac found a much more focused client in Guillermo Vilas, overseeing all aspects of the charismatic Argentine’s career. The partnership made both rich. In the early ’80s, Tiriac spotted a fairly unsung German teenager—and in due time, Boris Becker won Wimbledon and became a global superstar. Tiriac later claimed that Becker was partially responsible for the reunification of Germany. Other Tiriac-managed players included Henri Leconte and Goran Ivanisevic. Tiriac too is a Hall of Famer, inducted in 2013. He remains active in tennis, most notably as owner of the combined ATP and WTA event held in Madrid.

Resolutely independent, in May 2017, amid Nastase’s provisional suspension and an ITF investigation, Tiriac invited his former protégé to come on court for the ceremony that followed the Madrid women’s final, which had just been won by Romanian Simona Halep. Nastase’s presence upset the WTA. “He had no place on court today,” said WTA CEO Steve Simon in a statement, noting that the WTA had revoked Nastase’s credentials at its tournaments. Tiriac demanded the WTA apology for such criticisms of Nastase and, by implication, himself. According to an April 2019 Sports Business Journal article, Tiriac subsequently sued the WTA for defamation in Spain, Romania, and Cyprus.

But tennis was merely one small principality in Tiriac’s massive empire. He had become a billionaire. According to the website for his company, “the [Tiriac] Group currently brings together more than 40 local private companies, operating in the following main sectors: automotive, real estate, financial services (insurance, financial and operational leasing), air transportation and energy. In addition to the above, Tiriac Group carries out activities in several related fields—surveillance and protection, property management, media services, etc.”

Gorman helped the American Davis Cup team reach the finals in ’73, this time in Cleveland versus Australia. But after five years of tennis politics had kept the best Aussies from competing in Davis Cup, the rules were changed. The ’73 Australian squad was loaded, starring Laver and recent US Open champion Newcombe. On the first day, Gorman dropped a five-setter to Laver, and Smith lost one of similar length to Newcombe. Australia clinched the title when Newcombe and Laver beat Smith and van Dillen. At least that loss was free of cheating. In 1986, Gorman was named Davis Cup captain. Over the course of Gorman’s eight-year term, his teams won the title twice.

While still earning his degree at USC, van Dillen reached a career-high ranking of 36 and later went to work for sports marketing firm IMG. Solomon, Gottfried, and Dibbs enjoyed healthy stays in the top 10, collectively winning 69 singles titles.

Ralston was the Davis Cup captain until 1975. He was inducted into the International Tennis Hall of Fame in 1987. For 10 seasons, he led the men’s team at Southern Methodist University (SMU). From 1981 to ’87, Ralston coached Chris Evert and also worked with Yannick Noah and Gabriela Sabatini.

The case could be made that the ’72 American Davis Cup journey—five road matches, four on clay, culminating with the upset win in Bucharest—is the greatest team effort in tennis history. But there was one rogue cell in the red, white, and blue body that revealed how the sport’s structure and values—including the lure of Davis Cup—were turned upside down.

In March, at that first Davis Cup tie versus Jamaica, one member of the team was a fast-rising 19-year-old, Jimmy Connors. A hitting partner for the ’71 finals in Charlotte, Connors arrived in Jamaica red-hot, having won the first two singles titles of his career. Naturally, Connors assumed he would play. But Connors lost several practice matches that week and learned he would not be in the lineup. That same week, Connors’ grandmother, Bertha—a woman he was extremely close to, a co-coach alongside Connors’ mother, Gloria—fell gravely ill. Connors raced home. Miffed that her grandson was denied the chance to play, shortly before she died, Bertha told Gloria to never let Jimmy play Davis Cup.

Attuned to this was Connors’ new manager, Bill Riordan. Leader of an American indoor circuit of tournaments, Riordan held a belief that Donald Dell was conspiring to monopolize tennis and that the cabal included such Dell clients as Ralston, Smith, and several other Americans. Riordan exploited Connors’ desire to be independent, a sensibility long nurtured by his extremely guarded mother. After Connors and Gorman lost in the semis of the doubles at Roland-Garros in June ’72, the plan was for them to immediately fly to Mexico and join the American team for its next Davis Cup match. Connors did not make that trip.

Though Connors later made a few forays into Davis Cup, he never played for a Ralston-led team. Even more, Connors’ distance from such a prestigious event during his years as world No. 1 reduced its importance. During pre-Open feudal times, Davis Cup was mandatory, lest your national association bar you from competing elsewhere. But now, amid the opportunities and freedom provided by tennis’ market economy, Connors was the first of many who did not automatically commit to play Davis Cup. Connors didn’t need or care to be held accountable to a group, be it run by volunteer officials or his fellow players. He refused to join the ATP. Fittingly, at Roland-Garros in 1973, Connors paired for doubles with someone who’d also begun to heavily value independence: Nastase. The two reached the finals in Paris and the next month, mutually eschewing the ATP boycott of the world’s most prestigious tournament, won Wimbledon. Loyalty (and slavery?) to nation had given way to personal choice—and, yes, renegade behavior, Nastase and Connors both cantankerous enough to create the need for many new regulations. Connors is arguably the greatest player in tennis history never to have played for a championship Davis Cup team.

In 2002, Smith and Gorman were invited to Bucharest to play Tiriac and Nastase in an exhibition. Tiriac told Gorman he was surprised he’d shown up. But these many years later, true to his generous nature, Gorman had long forgiven Tiriac. Naturally, this was a far friendlier affair. Smith played a set of singles versus Nastase, paired with Gorman to take on the two Romanians, followed by a flag-switching cordial set pitting Smith-Tiriac against Gorman-Nastase. But even three decades later, it was wise not to have Gorman play Tiriac.

When the exhibition ended, Tiriac asked Smith where he was next headed. The American detailed several flights through Europe, including cumbersome layovers. Please, insisted Tiriac, take my plane. I’ll arrange everything. Polite to a fault, when Smith returned home, he wrote Tiriac a thank-you note.

***

One day in 1993, Ralston received a phone call. Once again, the messenger was Bud Collins. Once again, the culprit was the USTA, in this case, a pair of past presidents, Colwell and Stan Malless. Everyone knew that Ralston was the captain of the U.S. Davis Cup team from 1972 to ’75. But in 1993, Colwell and Malless contacted USTA president J. Howard “Bumpy” Frazer and requested that the annual USTA yearbook be amended to list Colwell as captain during the ’72 matches in Mexico, Spain, and Romania, and Malless as captain for a tie versus Chile. Without speaking to Ralston or anyone else, the change was made for the 1993 edition, with Ralston downgraded to coach.

Hearing this from Collins, Ralston was staggered. But unlike in ’72, when he and his team went along with the decision to go to Bucharest, this time Ralston fought back. He hired an attorney and obtained affidavits from all of the team members, and, eventually, the USTA properly reinstated Ralston as captain.

To file the affidavits in federal court, Ralston drove nearly three hours from his home in Colorado to Cheyenne, Wyo., in the thick of a massive snowstorm. As Ralston noticed various snowplows, as his car slid down the icy highway through the Rocky Mountains, he once again pondered death. In Bucharest, Ralston was one step from whacking Tiriac and possibly triggering an international incident. Now came another glance at mortality and deceit, this one courtesy of three leaders of Ralston’s national tennis association. As Ralston had learned, we may be through with the past, but the past is never through with us.

Joel Drucker is a frequent contributor to Racquet and is a historian-at-large for the International Tennis Hall of Fame.