By Joel Drucker

Madison Avenue Taught Tennis That Image Is Everything

It’s highly doubtful Pat Martin had any thoughts about tennis as he labored through crafting a campaign for the new product. The launch would happen in the summer of 1968. Martin was a 30-year-old copywriter at Leo Burnett, the massive Chicago-headquartered advertising agency that had sprung to life such icons as the Jolly Green Giant, Tony the Tiger, and, perhaps most notably for Martin’s assignment, the Marlboro Man.

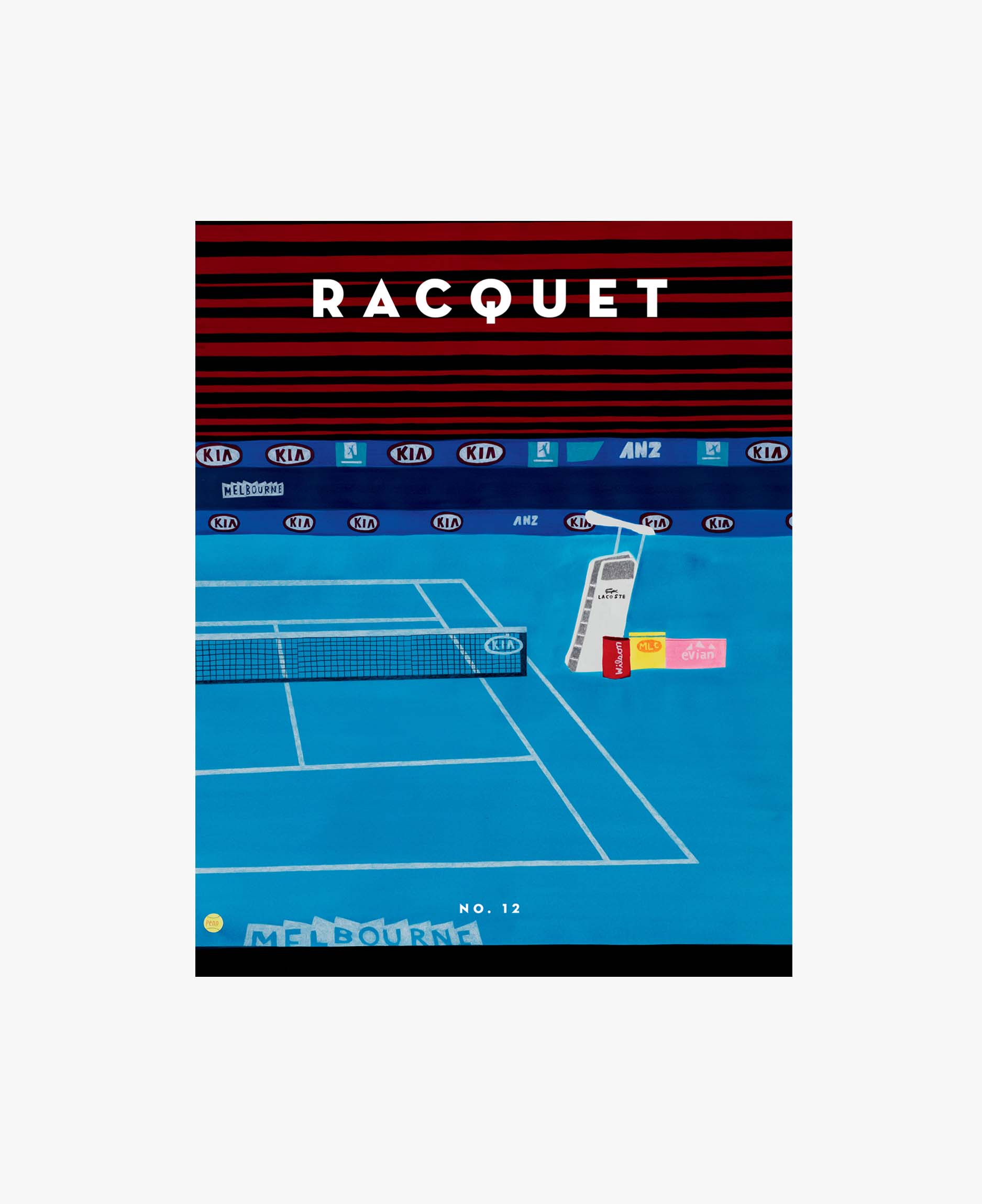

Marlboro’s parent company, Philip Morris, was about to unveil a new cigarette aimed exclusively at women—women who in these late-’60s days had begun to deploy such terms as “liberation” and “feminism.” The cigarette too had long been a sign of such feminine progress. Believe it or not, earlier in the 20th century, it was taboo for a woman to smoke in public. As women began to assert themselves in far bolder ways, why not offer a cigarette that was appropriately thinner to fit a woman’s slender hand and address them with a clever, hyper-contemporary advertising campaign?

For surely, in these tumultuous times, this product was no mere fashion statement. So if tennis wasn’t on Pat Martin’s mind, maybe this scenario was more fitting for articulating the cultural significance of Virginia Slims, a cigarette arguably infused not just with nicotine, but with a heady dose of zeitgeist.

***

Let us imagine it happened like this:

She preferred being called Katharine. Seven years earlier, Katharine had graduated Vassar, with hopes of becoming a writer. Now, in the spring of ’68, she was about to turn 30, working at one of Madison Avenue’s larger agencies. Invariably, everyone called her “Katie,” including her boss, John Whitworth, a Penn State grad who was one of the firm’s premier account managers. Katharine’s tasks included keeping track of John’s schedule, typing his correspondence, occasionally sending flowers to his wife, keeping track of his children’s birthdays, and fetching his coffee and dry cleaning. But it came to pass that through a series of random events—including Katharine being the only one in the room who could name all 10 Canadian provinces—Katharine was given the chance to assist several of the agency’s copywriters. Of course, she remained responsible for everything John-related.

“Look at Katie, proofreading that brochure,” he said on this morning in the spring of 1968. “Honey, would you please get me a Danish?”

As Katharine got up from her desk, John walked by. Per usual, each morning, he held a rolled-up newspaper in his hand. Giving Katharine a gentle whack on the tush with that day’s edition, John issued a statement of pride:

“You’ve come a long way, baby.”

***

Meet Virginia Slims, the cigarette with a tagline for the ages.

The last word had been a source of contention between agency and client. In one of those rare instances when the agency argued for restraint, the humble Midwesterners from Leo Burnett were concerned that “baby” was a derogatory term. For the Manhattanites from Philip Morris, it was affectionate, arguably even urbane and cool. The client being the client, “baby” it would be. As a Philip Morris advertising executive later remarked, “It was the shade of difference that lifted the whole thing a hundred feet in the air.”

Baby? Baby doll. Baby cakes. Baby fresh. A 1967 Beatles song, “Baby, You’re a Rich Man.” A hit film from the summer of ’68, Rosemary’s Baby, centered on a progeny sired by Satan. Baby, baby, baby, baby. You’re going places, but you’re still an infant. You have come. Light up. Have a smoke and inhale the personification of half the planet’s struggle for equality.

The creation of Virginia Slims was either a marketing pinnacle or nadir: the identification of a need and the creation of something to fill it. And yet, as events would unfold, no single advertiser did more to accelerate the growth of tennis—and, arguably, all of women’s sports—than Philip Morris and Virginia Slims.

***

Virginia Slims was introduced on July 22, 1968. Earlier that month, Billie Jean King won the Wimbledon singles title for the third straight time. Her reward: 750 British pounds ($1,800). At least this was better than the 45-pound ($124) gift voucher she’d received in ’67 upon winning the singles, doubles, and mixed.

That had been the last year of the pre-Open era, those awkward decades when tennis couldn’t get out of its own way. If you were an elite amateur like King and that year’s men’s champ, John Newcombe, you were compensated through a random and capricious mix of expenses dished out by national associations ($28 a day was common for Americans), under-the-table payments from tournament promoters (maybe $1,000 for that week’s event if you were ranked No. 1, considerably less for others), cushy jobs with racquet companies, and assorted trinkets acquired along the way. Those top players who dared try to earn a legitimate income as pros—Pancho Gonzales, Rod Laver, and Ken Rosewall among the notable—were instantly banned from playing such prestigious events as Wimbledon, the U.S. Championships, Roland-Garros, Davis Cup, Fed Cup. Save for a few short-term experiments, there was no women’s professional tennis.

Back in ’65, when Billie Jean had married Larry King, she anticipated that soon enough she would leave tennis and become a mother. In 1967, having won Wimbledon and the U.S. Championships, King grossed less than $20,000. That same year, the 23-year-old Newcombe, also the champ at those two events, also having made the same income as King, took stock of his career. He’d won the U.S. title largely on a diet of canned beans, was paid $5 a day by the Australian administrators, and figured the time had come to explore teaching-pro jobs.

Had you told either that in less than a decade, they would each be featured in ads for companies that had nothing to do with tennis, generate an annual income well north of six figures, and wear multicolored clothes while competing on national TV, you would have been considered as crazy as the notion that tennis balls would become yellow and that the two-handed backhand was going to change the sport.

But the ’60s were revolutionary, the world riding a wave of social change that tennis too would eventually hop aboard. View the civil rights movement as fundamentally a triumph of the individual. If the social justice movement was rising to address racial inequality, it also empowered everyone from politicians to entertainers to artists to athletes to view themselves not merely as cogs in a machine, but as singular, dynamic entities, oozing a word that would become prominent throughout the ’60s: charisma.

This was the decade when pop artist Andy Warhol popularized the word “superstar.” Naturally, it was also a decade when advertising created a way to assess personalities. Nineteen sixty-three marked the birth of the Q Score, popularly known as the Q rating, an assessment of familiarity and appeal. “Ad agencies lived by it,” said Cliff Einstein, a longstanding creative director, most notably for the Los Angeles-based agency Dailey & Associates. “You want somebody that seems to fit, without overpowering the brand.”

With television now America’s primary communal gathering spot, visual images strongly shaped attitudes. A likely tipping point in the 1960 presidential campaign had come at a debate between John Kennedy and Richard Nixon. Kennedy, attired in a snug suit and crisp makeup, appeared far more composed and downright better-looking than the sweaty, gaunt Nixon. “One could vote for glamour or for ugliness,” wrote Norman Mailer in a seminal 1960 Esquire article, fittingly titled “Superman Comes to the Supermarket.” In his 1961 book, The Image: A Guide to Pseudo-Events in America, historian Daniel Boorstin lamented how various debates, talk shows, and discussions trivialized public discourse, “as if the contestants were adversaries in an intellectual tennis match.” Fancy that, Kennedy and Nixon, their bodies, faces, and words, wielded like racquets.

Meanwhile, on the literal front, tennis remained hindered by twisted politics, corrupt economics, and exclusionary venues. The sport lurched and struggled to gain cultural traction. Jack Kramer, the best player in the world in the ’40s and ’50s, had for years run the professional barnstorming tour. Year after year, Kramer had unsuccessfully advocated for Open tennis—amateurs and pros, competing together for prize money at all the big tournaments—though his focus was on the men. In late 1967, a newcomer to the sport, Dave Dixon, had signed Newcombe (for $55,000) and seven other top amateurs to pro contracts, forming a traveling retinue dubbed the “Handsome Eight.” The stuffy and corrupt leaders who ran tennis’ central organization, the International Lawn Tennis Federation (ILTF), viewed the likes of Kramer and Dixon as craven capitalists.

In the end, the conclusive blow had been delivered not by the barbarians, but from those deep inside the castle. Herman David, chairman of the All England Club, wanted nothing more than for Wimbledon to feature the very best tennis players in the world. Having hosted a successful eight-man pro event in August 1967, David that fall declared that the 1968 edition of the tournament would be open to all. Once tennis’ preeminent event opened the gates, others soon followed. Consider what Wimbledon had done a case of conceit turned into inclusion.

Open tennis revolutionized tennis economics. King signed a pro contract for $40,000. Newcombe was paid $10,000 to use a Slazenger wood racquet in Australia, Europe, and Great Britain, and $30,000 to play with a metal Rawlings frame in North America. Deals with clothing and shoe companies beckoned. Beyond sporting goods, though, advertisers who’d previously been unable to find a suitable entry into the sport began to explore how this new fashionable kid on the jock block might aid their brands. And who better to help advertisers see the way than the publisher of tennis’ leading magazine?

Enter Gladys Heldman. The daughter of a prominent New York attorney and judge, Heldman had graduated Stanford in three years and earned a master’s degree in medieval history at UC Berkeley. Having married a former national junior champion, Julius Heldman, she’d learned the game late and become a tennis zealot. But as a Jew, Heldman was an outsider in the patrician, WASP-dominated tennis world. With her own mix of defiance, moxie, and intelligence, she forged her own path. In 1953, the year she turned 31, Heldman founded World Tennis, a magazine that by the ’60s was the sport’s preeminent publication. Heldman had often used her pages to advocate for change, including devoting extensive attention to women’s tennis.

She was also an activist. In 1962, distraught to learn that very few Europeans were planning to play the U.S. Championships, Heldman personally raised $18,000 to cover the cost of a charter jet to bring 85 players to New York. Seven years later, she staged three women’s tournaments in Philadelphia, New York, and Dallas.

Heldman cultivated such business leaders as another Jew, Philip Morris CEO Joseph Cullman. Excluded from such clubs as the West Side Tennis Club (home of the U.S. Championships), they huddled and played tennis together frequently at the Century Country Club, a Westchester County venue with a great many Jewish members.

If Cullman’s business objective was to generate sales of cigarettes, that mission was also paired with a social consciousness. As Cullman said in 1998, “I became interested in tennis as a ‘project’ in the 1960s, when the sport was dominated by club types who played at restricted clubs…. I was not happy with the lack of diversity—racial, religious, gender, and economic—of the players and those in the stands…. More change was on the way, in the form of Pancho Gonzales, Althea Gibson, Arthur Ashe, Manuel Santana, Billie Jean King, and a host of other minority and female players. It was something like the situation Jackie Robinson faced in baseball after the war. I appreciated that it takes time for people to change attitudes, but tennis wasn’t moving fast enough until the Marlboro CBS-TV national sponsorship changed things.”

Prior to Open tennis, the Marlboro Award, celebrated in the pages of World Tennis, honored tennis folk who’d made notable contributions to the sport beyond the playing field. Throughout the ’60s, Philip Morris also had four tennis players—Ashe, Santana, Rafael Osuna, and Roy Emerson—on staff as public relations executives (what now would be called “brand ambassadors”).

Thanks to Philip Morris, a new $167,000 electric scoreboard that boasted the Marlboro logo and the words “Come to Marlboro Country” adorned the grounds of the 1969 US Open. Cullman that year began a two-year run as tournament chairman. National TV coverage on CBS had begun in 1968. Here again, Cullman made a major impact, increasing the rights fee from $50,000 in ’68 to a five-year deal at $100,000 annually. “I think tennis is on the threshold of a forward movement,” he told The New York Times in September 1970. “It has all the qualities of success but it needs more leadership. The people mean well, but the structure of the U.S.L.T.A is archaic and the sport has a lot of built-in prejudices. People in the sport think of the game as they know it, not as the public appreciates it.”

The next summer, prior to the US Open, Heldman learned that Kramer, tournament director of the Pacific Southwest Open—a Los Angeles-based event that in those years was considered the second-most important tournament in America—was offering far more money to the men than to the women: $12,500 for the men’s winner, $1,500 for the women’s champ. Any woman who failed to reach the quarters would not earn a penny.

Heldman suggested a boycott of Kramer’s tournament and that King and her peers play an event with a $5,000 purse in Heldman’s new base, Houston. She also asked Cullman to chip in a few more dollars, raising the total to $7,500. Thus was born the Virginia Slims Invitational. Nine players, including King, Casals, and Heldman’s daughter, Julie, signed contracts with Gladys for one dollar apiece to join what would shortly become the Virginia Slims Circuit.

Here is where, of all people, that less-charismatic candidate, President Richard Nixon, did something that eventually aided the cause of tennis. On April 1, 1970, Nixon signed the Public Health Cigarette Smoking Act, a piece of legislation that banned cigarette advertising on television and radio starting in 1971. Philip Morris went out in style, buying $1.25 million worth of airtime for those final 30 minutes. As fate had it, the last cigarette ad to air on American television was a Virginia Slims commercial.

Tennis also benefited from another advertising trend that began to surface in the ’70s. In the ’60s, amid the ascent of color TV and a flush economy, a great many campaigns had been aimed at broad audiences. But as the new decade got underway, with the economy beginning to constrict and competitors from around the world starting to make inroads, marketers sought greater accountability from their advertisements. One way to do this was to connect with consumers in a more targeted way. “Segmentation became important during that time,” said Einstein, who years later featured teen prodigy Tracy Austin in an ad for Knudsen yogurt.

There you had it: a cigarette aimed at young, vibrant, cheerful women. Dare you ask for a better showcase than highly skilled athletes? And what to do with many of those dollars once earmarked for television? The 1971 rendition of the renamed Virginia Slims Circuit would consist of 19 tournaments and $309,100 in total prize money.

Appear in advertisements? Better yet: Women’s tennis players were the advertisement. Athletic prowess, economic empowerment, and, yes, fit physiques all meshed perfectly with the Virginia Slims message. Summarizing the results of the 1971 campaign—including King becoming the first female athlete ever to earn $100,000 in a calendar year—Heldman closed out her piece with these words: “You’ve come a long way, baby.” A slight twist: A Long Way, Baby was the title of a book, New York Times reporter Grace Lichtenstein’s compelling tale as an embedded reporter on the 1973 Slims circuit. Fifteen years later, King and journalist Cynthia Starr would craft a comprehensive history of women’s tennis titled We Have Come a Long Way. Pat Martin likely wondered why he hadn’t patented his slogan.

Herein, alas, for better or worse, in sickness and in health, for love and tennis, we arrive at the inherent contradiction between the authenticity of a sport and the artifice of an advertisement; worse yet, an advertiser offering a product with potentially lethal consequences. “We made a deal with the devil,” said Julie Heldman. Her form of protest was to decline to wear dresses that were adorned with the “Ginny” artwork featured in Virginia Slims ads. The alliance with tobacco mattered little to Gladys, who regularly smoked two packs a day and three during that crush period when the magazine went to press.

In a written response to my inquiry, King wrote, “I remember when Gladys Heldman told us Philip Morris and Virginia Slims were going to be our sponsor. I didn’t smoke and I wasn’t comfortable initially with the idea of a tobacco company as our sponsor. I remember telling Gladys, ‘We are athletes, this isn’t right.’ She looked at me and said, ‘You want a tour or not?’ But Philip Morris was perhaps the greatest sports partnership ever in the history of sports. They never asked us to endorse their product. They never asked us to smoke. They told us we could say whatever we wanted. They put the emphasis on the players and women’s tennis. One of the best things they did was make us celebrities and not just tennis players. They added value to tennis, to women’s sports and definitely to all of us. They committed fully to growing tennis, they gave women’s tennis a foundation, an infrastructure that is at the core of the WTA Tour still today.” King would later serve on the Philip Morris board of directors from 1999 until 2003.

Nearly 50 years after the women’s pro tour started, it’s tempting to view tennis’ alignment with tobacco with piety and righteousness. Yet here was a group of athletes eager to earn a legitimate living. Here was a sophisticated marketer keen to not just offer prize money, but provide the young athletes with a cadre of experts, happy to assist with the creation and execution of events, marketing, public relations, banners, flyers, TV coverage, administrators, and all the professionalism tennis had long lacked. In this instance, a Fortune 500 company represented change and supported a movement Gladys Heldman dubbed “Women’s Lob.”

On the other end, there was the USLTA, the ILTF, and all the other masters of the tennis establishment that treated women like second-class citizens. As Heldman planned the Houston tournament, word spread that the women would be suspended and subsequently banned from playing Grand Slam events. At one point, Stan Malless, a USLTA official, agreed that Heldman’s Houston tournament could happen, so long as it was labeled an amateur event and the competitors were compensated under the table.

Though neither of these things happened, the rumored threats only exacerbated the players’ sense that it was far better to join forces with a thoroughly professional Fortune 500 company than to serve at the mercy of the inbred and capricious amateur world. One was reminded of the story of the Holocaust survivor who told his friend he planned to leave Europe and head to Australia. But it’s so far, said the friend. Said the survivor: Far from what?

“The USLTA did not want us to succeed,” said Julie Heldman. “We were going from a world where clubs ran tournaments to a public world, with public facilities that welcomed us and built stands and filled them.”

It’s highly likely that without Virginia Slims, the 1973 formation of the WTA would not have happened. And without the WTA, what becomes of not just women’s tennis—by far the most prominent women’s sport in the world—but all of women’s sports? “Without the support of Philip Morris,” wrote King, “women’s tennis would most likely not be the leader in women’s sports it is today. The people who were part of the Philip Morris family had the greatest levels of integrity and continued to help the sport, the players, and me personally, long after their sponsorship ended. That says a lot about who they were and how important their contribution was.”

And the Q ratings of tennis players rose dramatically. “Tennis was at its peak and my name recognition was never higher than it was after the King-Riggs match,” wrote King in her email to me. “Tennis was the first women’s sports to break through on a wide commercial scale…. We were new and people love new. From a business side everyone came together and we all won.”

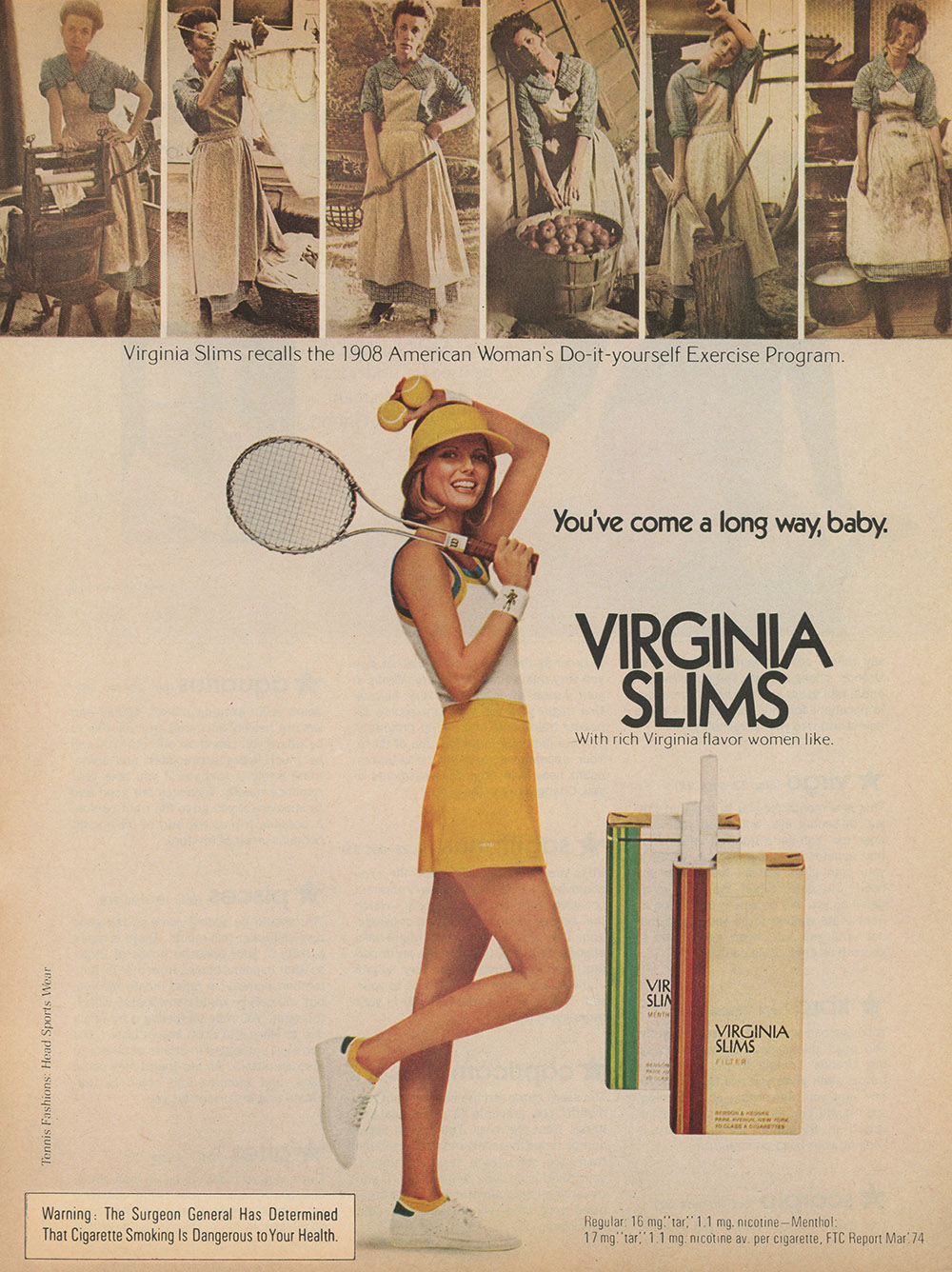

The ascent of segmentation that perfectly connected Virginia Slims with women’s tennis also made the sport appealing to such marketers as Volvo, the sturdy Swedish car, and Colgate, a toothpaste eager to take on that titan known as Crest.

“The demographics for Volvo were perfect,” said Ray Benton, the longstanding agent who for years was directly involved in Volvo’s extensive tennis commitment—from several pro tournaments, to sponsorship of the overall men’s tour standings, to such recreational activities as a form of team competition that is the ancestor of contemporary USTA NTRP league play (throughout the ’80s, it was common to say you were playing “Volvo” versus another facility). Explained Benton: “Volvo is a pretty small brand, but its audience is highly educated, possessed of a certain affluence and responsibility. Tennis was a great way to really target that specific demographic.”

Colgate was another company Benton helped shepherd through tennis. Lacking the financial resources to compete with Crest in paid-for advertising, Colgate opted instead to hitch its wagon to high-impact experiences that would generate TV coverage and additional exposure (this was similar to the Virginia Slims strategy). By the ’80s, this was familiarly known as “event marketing,” but in the early ’70s, the approach was quite a radical departure from merely purchasing advertising time on television.

Yet while a women’s cigarette and a no-nonsense car appeared a sharp fit for tennis, the sport’s connection with toothpaste was vague. Recently, an executive with Colgate’s advertising agency during the ’70s told me that “We weren’t sure if tennis was best for the brand.” In the biz, though, as the hesitant Leo Burnett team had learned with the word “baby,” client trumps agency. The Colgate-Palmolive CEO, David Foster, simply loved the sport and, with the zeal of a dictator, demanded his executives put tennis front and center in many of its campaigns, from print and broadcast advertisements to sponsorship from 1978 to ’80 of the men’s season-ending tournament, dubbed the Colgate Masters (the next year, it became the Volvo Masters).

Even beyond applying its logo near tennis players and tournaments, Colgate in the early ’70s purchased Bancroft, a longstanding racquet manufacturer, as well as Mission Hills Country Club, a venue located in the Palm Springs area. Bancroft signed such stars as King and a rather alluring Swedish prodigy, Bjorn Borg. In ’77 and ’78, Mission Hills was the venue for a major WTA event known as the Colgate Series Championships (it continued under the Colgate name for four more years at other venues), hosted the Davis Cup finals in ’78, and, beginning in ’76, was the first home for the ATP men’s event that is now played at Indian Wells.

Tennis was going supernova. It was estimated that in 1960, 5.5 million Americans played tennis. Ten years later, a study conducted by A.C. Nielsen—the same company that measured TV ratings—estimated that there were 10 million American tennis players. By 1976, the figure had nearly tripled. “Tennis was an aspirational sport,” said Benton. “To be cool, you wanted to be like those people. In the days of the tennis boom, the CEO played tennis. If the CEO played tennis, then there was a good chance the senior vice president played—and then others. That’s how you entertained.”

Not too long ago, tennis wanted to be welcomed to the party. By the mid-’70s, the opposite was often the case. Marketers didn’t just want to showcase tennis players in their advertisements. They wanted to embed themselves into the tennis. The story goes that one day Mark McCormack, head of sports marketing firm IMG, took the CEO of Rolex—the upscale watch brand—to the All England Club. The tournament was not taking place on this day. As the man from Rolex sat with McCormack on the isolated Centre Court, as he took in all of Wimbledon’s luscious texture and charm, history and greenery, he issued a three-word statement: “This is Rolex.”

Thus commenced a partnership that began in 1978 and has continued for more than 40 years, with advertisements featuring such stars as Newcombe, Laver, Borg, Chris Evert, and, most recently, downright obviously, Roger Federer. “Rolex is not a watch,” said Beth Doerr, an American journalist based in Germany who covers the watch industry. “Rolex is a lifestyle product that happens to have a watch. Wimbledon is the holy grail of tennis. It’s also the most elegant part of tennis, so the connection with Rolex is perfect: winners, elegance, exposure all over TV.”

The shifting landscape of sports also made tennis players highly attractive for advertisers. In the early ’60s, famed art director George Lois had used such athletes as boxer Joe Louis; baseball greats Mickey Mantle, Willie Mays, and Yogi Berra; basketball stars Oscar Robertson and Wilt Chamberlain; and pro quarterbacks Don Meredith and Johnny Unitas to hawk a spectrum of products ranging from breakfast cereal to cat food to financial services. “The love affair between Madison Avenue and sports was very intense,” said Robert Lipsyte, who covered sports for The New York Times from 1962 to ’71. “Athletes were wonderfully controllable for advertisers.” Well, at least for a time.

By the late ’60s, athletes were beginning to assert themselves. An Olympic gold medalist named Cassius Clay had changed his name to Muhammad Ali and refused induction into the Army. Others such as Bill Russell and Jim Brown became outspoken advocates for civil rights. Upon receiving medals at the 1968 Olympics in Mexico City, Tommie Smith and John Carlos raised their fists in protest. Curt Flood questioned baseball’s reserve clause that bound a player to a team as if he occupied a plantation. Said Flood, “A well-paid slave is nonetheless a slave.”

All of this activism disturbed Madison Avenue. Said Lipsyte, “They had to create an honorary white guy out of O.J. Simpson to counterattack Ali and Jim Brown.” The desired jock spokesperson was the kind of fella who gave his all on the playing field by day and enjoyed himself quite nicely (with a drink, not a drug) by night.

Tennis players fit the bill perfectly—especially as the game soared into public consciousness in the early ’70s. Lois featured the petulant but charming Romanian Ilie Nastase in an ad for Royal Air Maroc. “I liked his reputation as a rogue,” Lois told me recently via email.

Spicing up the mix was another aspect of the zeitgeist that fit tennis like a glove: sex. In the times we now occupy, it is hard to imagine just how increasingly sexualized American society had become in the ’60s and ’70s, that period between the introduction of the birth control pill and the onset of AIDS. Tennis clicked into this gestalt too. Leave the bulky, body- and face-cloaking uniforms to the other sports. Tennis players would reveal themselves in shorts and skirts.

Consider the very title of the infamous 1973 match between King and Bobby Riggs: “The Battle of the Sexes.” Riggs, clearly more of a believer in personal publicity than anything related to gender issues, had said he thought women best belonged in the kitchen and the bedroom. Countered King, “The bedroom’s fine; it’s the kitchen I don’t like.” Riggs during that match had worn a bright yellow jacket endorsing “Sugar Daddy”—technically a piece of candy, but also slang for a man sleeping with a much younger woman.

Arthur Ashe navigated the times exquisitely. Confronted by activist Jesse Jackson that he wasn’t appropriately militant, Ashe countered with the lightning-fast reflexes and workable message you’d expect from someone who excelled at an individual sport: You do it your way, Jesse. I’ll do it mine.

Ashe campaigned for Bobby Kennedy in the 1968 California primary. The next year, Ashe and his closest friend, Charlie Pasarell, formed the National Junior Tennis League, an inner-city tennis program that rapidly became the model for many such efforts throughout the country. Told by a member of an old-school club that some of their best players were black, Ashe asked, “Why aren’t some of your worst?” “Advantage Ashe,” a thoughtful column he wrote on various issues related to tennis, politics, and society, ran in places such as World Tennis and was sponsored by the Philip Morris-owned Miller Brewing Company.

In the early ’70s, Ashe pushed hard to visit South Africa, a landmark trip he took in November 1973. One month prior, Ashe shot an ad for Simmons Beautyrest, a mattress company. “Beautyrest supports my back,” said Ashe, “which supports my backhand, which supports me.” Joked Ashe in the book Portrait in Motion, a diary he kept for that year, “Imagine a black guy doing a commercial for sleeping. A lot of white people always figured we weren’t good for anything else.”

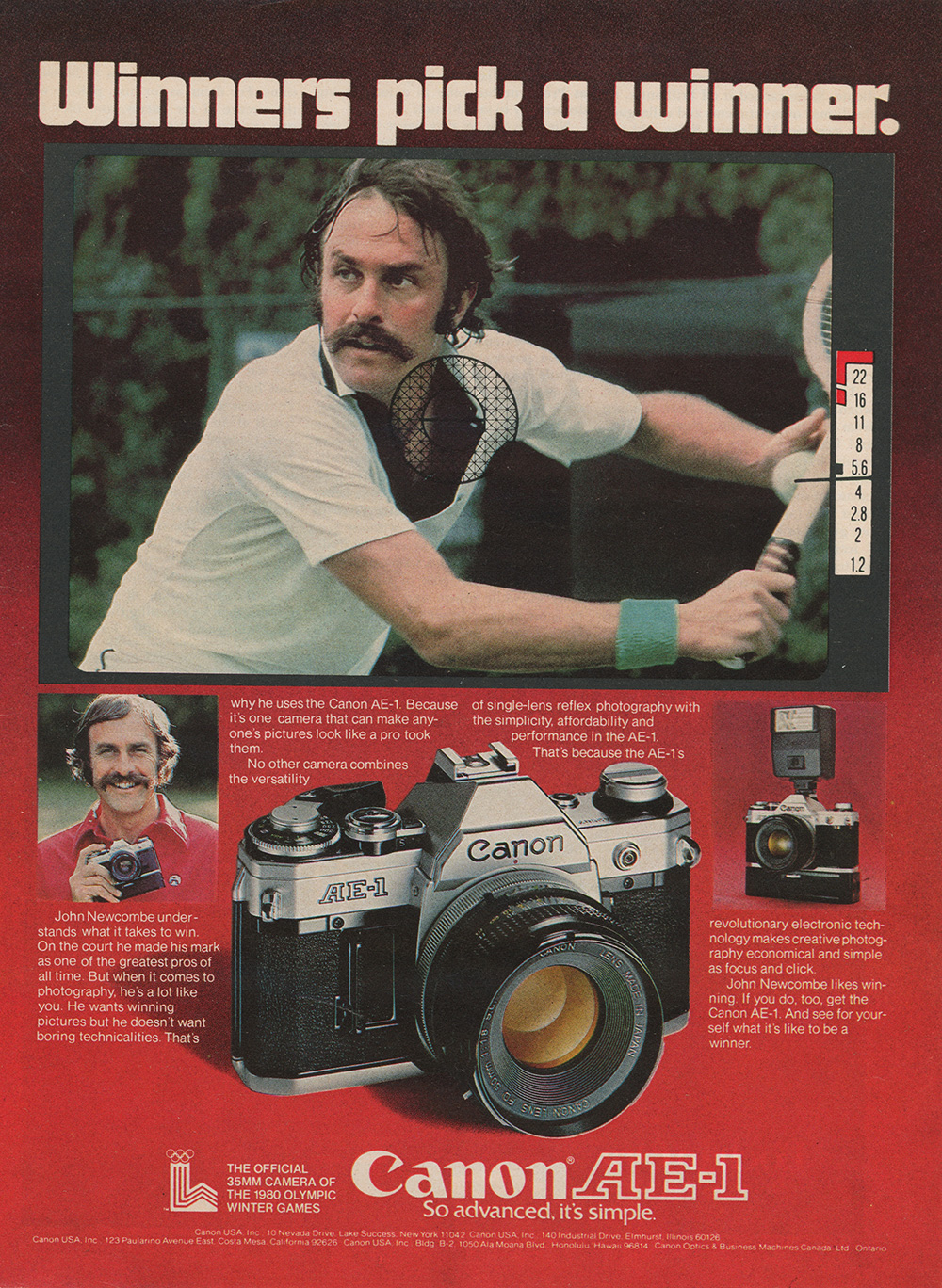

But when it came to the right person in the right place at the right time, no one in those tennis boom years of the ’70s captured Madison Avenue more successfully than Newcombe. His credentials were impeccable: three Wimbledon singles titles by the end of ’71, a second U.S. championship in ’73, a Davis Cup win with Laver later that same year, a resurgent rise back to No. 1 in ’74, an emphatic Australian Open finals win over Jimmy Connors in ’75.

Added to this was the exotic lure of Australia. Years before the 1986 film Crocodile Dundee, Newcombe vividly personified all that made the land Down Under attractive to Americans. Newcombe’s commercial appeal soared soon after winning his second Wimbledon singles title in 1970, when he grew a mustache that became catnip for a wide range of marketers, from coffee and boots to jewelry, cheese, cameras, and, in time, his own line of clothing. From appearances on the cover of GQ and Sports Illustrated, to coauthoring The Family Tennis Book with his wife, Angie (a former world-class player), to rollicking good times at his Texas tennis ranch and around the world with family, friends, and such celebrities as playwright Neil Simon, actor Peter Ustinov, and comedian Alan King, “Newk” was as natural an advertising spokesperson as tennis has ever seen. No tennis player better personified the quarterback-like matinee idol advertisers craved.

The campaign for the Canon AE-1 camera was quintessential Newcombe. The print ads and commercials depicted Newcombe at his charming and athletic best, be it with his own tennis, a friendly interaction with a recreational player, or a role reversal with professional tennis photographer Fred Mullane (one of the best in the sport and still active). “John was a real swashbuckler who knew precisely what these situations called for,” said Mullane, who also noted that the producers of the ad stipulated that Mullane shave off his own mustache—perhaps to avoid any confusion about who the real sex symbol of the ad really was.

Indeed, the notion of the tennis player as a source of attraction was what inspired journalist Dan Wakefield to write the 1974 Esquire article “My Love Affair With Billie Jean King.” Previously having had zero affinity for tennis, Wakefield found himself struck by, of all things, a Colgate ad featuring King. Shot in her San Francisco Bay Area apartment, a barefoot King wore gray slacks and a white top. With a cat on her lap, a guitar to her right, lacking her usual glasses, King looked much like a “coed,” the term often used then for the many women who had begun to integrate a number of previously all-male colleges. Though years later King would praise how the ad did not address her looks, but instead focused on her skills and impact, Wakefield viewed her quite differently.

Based in Boston at the time, Wakefield rapidly found himself less engaged by the Red Sox and more drawn to women’s tennis—but not due to anything that necessarily had to do with anyone’s proficiency at volleys or ground strokes.

“I watched Billie Jean beat Chris Evert, and my enthusiasm grew,” wrote Wakefield. “Chris Evert was a standard American beauty type, the kind who gets all the high-school Prom Queen and Sweetheart of Sigma Chi awards, and who snubs you in the halls. It all made sense when I later learned that among the women players she was known as ‘The Ice Dolly.’ Billie Jean was more human, her emotions expressed at every point by frowns and smiles and gestures and mannerisms that revealed without any subtlety just how she felt at any given moment. And with all of it, sweating, running, hitting, she seemed, to me anyway, enormously appealing.

“I began to talk about Billie Jean to male friends and found that, all of a sudden, most every man I knew had his favorite woman tennis player, just as he used to have, but just didn’t much care anymore, his favorite movie actress. It’s been years since I’ve heard a heated discussion among men about their favorite movie stars, certainly not as sex symbols. Not since Marilyn Monroe, really.”

There followed a scene out of a John Updike story. At a suburban dinner party, with two married couples and a young woman, Wakefield asked the men to choose whom they would prefer to have an affair with—King, Evert, or Evonne Goolagong. The dialogue touched on a range of notions that if printed today would likely earn the author a one-way ticket to some variation of the Witness Protection Program.

Said Lichtenstein, “This kind of discussion in an article was perfectly acceptable then.” Lichtenstein also had a cameo in the article, voicing her objections to the ad: “That’s not Billie Jean—she had makeup on and she didn’t have on her glasses.” Along with Wakefield, Lichtenstein’s fellow New York Times writer Neil Amdur emphatically made the case for King’s sex appeal. As Wakefield recently told me, “She represented a new kind of woman. She was something new, the first of a new breed.”

Wakefield went on to cover the King-Riggs match (including a conversation with a female journalist who conjectured about the length of Riggs’ penis), dissect a nuanced profile of King written in Ms. magazine by noted tennis writer Bud Collins, interview King in Los Angeles, and, in the end, craft one of the more intriguing tennis profiles ever written—the kind of high-access, angled portrait authored quite frequently in those glorious magazine days of the ’70s (publications that often boasted many advertising pages courtesy of TV-deprived tobacco companies).

All this, propelled by a toothpaste ad with a rather innocuous headline: “If Colgate is just a kid’s cavity fighter, how come Billie Jean King won’t brush with anything else?”

***

The decade following the start of Open tennis had been remarkable, the miracle of tennis’ ascent something out of a Dickens novel. As late as 1967, in the family of sports and popular culture, tennis had been some sort of remote aunt and uncle, engaging and even beautiful to those who knew them, but also eccentric, sclerotic, and downright arcane. Then, starting in 1968, it had been discovered, a Golden Child of sorts. The sport had grown enough in its own right to create a dynamic advertising culture that included colorful print and television ads for racquets, shoes, clothing. World Tennis’ circulation leaped from 43,000 in 1968 to 325,000 in 1977.

No one, though, can remain an ingenue forever. In the early ’80s, two things happened that jarred tennis into adolescence and adulthood, forever changing its relationship to both itself and the advertising world.

The first was the end of the tennis boom.

Katharine, now a senior copywriter, was one of the millions who’d picked up tennis in the early ’70s and attended the local Virginia Slims event. She’d always remember that Friday morning in September ’73 when she collected $20 on the bet she’d made with John on the King-Riggs match. “Honey,” he said, “you beat me fair and square this time.” Once Katharine started playing tennis, though, she found herself spending far too much time picking up balls than hitting them. And when a round of layoffs hit the agency in ’82, time was at a premium. Putting aside her metal racquet, Katharine each morning now took a 30-minute aerobics class.

By the mid-’80s, tennis was no longer growing by leaps and bounds. Many pro events in North America ceased to be. Public courts were no longer overcrowded. Tennis shops closed. Equipment sales slumped. At least wood racquets had worn out. But the newer metal and graphite frames lasted for years.

If market maturity and even decline was but a natural form of cultural and economic correction, the second occurrence was far more of a jolt, an event that revealed much about the moral decay that often nestles inside the core of advertising.

In the spring of 1981, Marilyn Barnett, a former assistant to Billie Jean King, announced that she had previously been King’s lover and intended to sue for half of King’s earnings over a seven-year period, as well as partial ownership of a Malibu beach house. What was dubbed a “galimony” suit was thrown out of court in November 1982.

More immediate was the impact on King’s array of commercial endorsements—a flock of campaigns that all fizzled rapidly. A planned Wimbledon clothing line featuring King scrapped a $500,000 deal. Ditto for Murjani jeans ($300,000), Charleston Hosiery ($45,000), another $90,000 with a Japanese clothing company—and so on. When it was all settled, between legal fees and lost opportunities, King’s conservative estimate was that she’d lost nearly $1.5 million.

Spend time working in the world of advertising agencies and public relations firms—as I did for 10 years—and you will see that social meaning is of little concern to marketers. Had Philip Morris not created a cigarette aimed at women, how much money would it have committed to the cause of women’s tennis? That’s not the biggest question. The more pointed question is the one asked whenever a concept is reviewed by an advertising agency: Will it sell? Or as the Nixon administration had worded it, will it play in Peoria? This was a reference to a small Illinois town considered the epitome of mainstream America.

It didn’t matter that King had won more Wimbledon titles than anyone in tennis history. It didn’t matter that she’d crusaded for equal rights. It didn’t matter that NBC Sports had stood by King and kept her on its broadcast team for Wimbledon that summer of ’81. It didn’t matter that weeks after King had openly confessed that she’d been involved with Barnett, she had played a World Team Tennis match in ultraconservative San Diego and received a standing ovation. “After that I knew that it wasn’t any majority and certainly not a moral one that disapproved of me,” King wrote in her 1982 autobiography. What mattered as of the spring of 1981 was that to those who made decisions within corporations and advertising agencies, it was believed that Billie Jean King could no longer sell. Live by the Q, die by the Q. Or as one popular saying goes, a cynic is someone who knows the price of everything and the value of nothing.

***

The decade following the start of Open tennis had been remarkable, the miracle of tennis’ ascent something out of a Dickens novel. As late as 1967, in the family of sports and popular culture, tennis had been some sort of remote aunt and uncle, engaging and even beautiful to those who knew them, but also eccentric, sclerotic, and downright arcane. Then, starting in 1968, it had been discovered, a Golden Child of sorts. The sport had grown enough in its own right to create a dynamic advertising culture that included colorful print and television ads for racquets, shoes, clothing. World Tennis’ circulation leaped from 43,000 in 1968 to 325,000 in 1977.

No one, though, can remain an ingenue forever. In the early ’80s, two things happened that jarred tennis into adolescence and adulthood, forever changing its relationship to both itself and the advertising world.

The first was the end of the tennis boom.

Katharine, now a senior copywriter, was one of the millions who’d picked up tennis in the early ’70s and attended the local Virginia Slims event. She’d always remember that Friday morning in September ’73 when she collected $20 on the bet she’d made with John on the King-Riggs match. “Honey,” he said, “you beat me fair and square this time.” Once Katharine started playing tennis, though, she found herself spending far too much time picking up balls than hitting them. And when a round of layoffs hit the agency in ’82, time was at a premium. Putting aside her metal racquet, Katharine each morning now took a 30-minute aerobics class.

By the mid-’80s, tennis was no longer growing by leaps and bounds. Many pro events in North America ceased to be. Public courts were no longer overcrowded. Tennis shops closed. Equipment sales slumped. At least wood racquets had worn out. But the newer metal and graphite frames lasted for years.

If market maturity and even decline was but a natural form of cultural and economic correction, the second occurrence was far more of a jolt, an event that revealed much about the moral decay that often nestles inside the core of advertising.

In the spring of 1981, Marilyn Barnett, a former assistant to Billie Jean King, announced that she had previously been King’s lover and intended to sue for half of King’s earnings over a seven-year period, as well as partial ownership of a Malibu beach house. What was dubbed a “galimony” suit was thrown out of court in November 1982.

More immediate was the impact on King’s array of commercial endorsements—a flock of campaigns that all fizzled rapidly. A planned Wimbledon clothing line featuring King scrapped a $500,000 deal. Ditto for Murjani jeans ($300,000), Charleston Hosiery ($45,000), another $90,000 with a Japanese clothing company—and so on. When it was all settled, between legal fees and lost opportunities, King’s conservative estimate was that she’d lost nearly $1.5 million.

Spend time working in the world of advertising agencies and public relations firms—as I did for 10 years—and you will see that social meaning is of little concern to marketers. Had Philip Morris not created a cigarette aimed at women, how much money would it have committed to the cause of women’s tennis? That’s not the biggest question. The more pointed question is the one asked whenever a concept is reviewed by an advertising agency: Will it sell? Or as the Nixon administration had worded it, will it play in Peoria? This was a reference to a small Illinois town considered the epitome of mainstream America.

It didn’t matter that King had won more Wimbledon titles than anyone in tennis history. It didn’t matter that she’d crusaded for equal rights. It didn’t matter that NBC Sports had stood by King and kept her on its broadcast team for Wimbledon that summer of ’81. It didn’t matter that weeks after King had openly confessed that she’d been involved with Barnett, she had played a World Team Tennis match in ultraconservative San Diego and received a standing ovation. “After that I knew that it wasn’t any majority and certainly not a moral one that disapproved of me,” King wrote in her 1982 autobiography. What mattered as of the spring of 1981 was that to those who made decisions within corporations and advertising agencies, it was believed that Billie Jean King could no longer sell. Live by the Q, die by the Q. Or as one popular saying goes, a cynic is someone who knows the price of everything and the value of nothing.

***

Thirteen years into the Open era, tennis had entered adolescence. No longer the dotty aunt or uncle of pre-Open times, it had also ceased to be the young darling, the blossoming sport with the exotic, ascending stars—King, Newcombe, Ashe, Connors, Evert.

Worry not, there would continue to be tennis stars in advertisements. Yet in certain ways the sport had reached its own level of familiarity and mild eccentricity. In the family of sports, tennis had become the flashy, well-attired, quirky nephew or niece, the one who travels the world and intermittently surfaces with something rather dashing. Highly obscure prior to 1968, tennis players had become in many ways what they’d long hoped to be: celebrities, known for being famous and, for advertising purposes, palatable.

For a long time, Martina Navratilova was collateral damage in this environment. Though she dominated the ’80s, arguably even more so than hockey star Wayne Gretzky, quarterback Joe Montana, or basketball’s Magic Johnson, in those years a lesbian was advertising poison. “All most other advertisers could see was the fact I’m a lesbian,” Navratilova told The New York Times in 2000. “Everything else, they threw out.”

As Lois wrote in his book $ELLEBRITY, “When a Big Idea campaign has the power to become new language and startling imagery that enters the popular culture, advertising communication takes on a dimension that leaves competitive products in the dust.” Note this word: products. For all the ways creative directors wax about narrative and storytelling and brand affinity, advertising is most of all about the transaction of inanimate objects and various services, be it in 30 seconds over the airwaves or one page; a mélange of sights and sounds.

Only in the mid-’90s, by which time Madison Avenue could safely publicly acknowledge gays as a legitimate audience worthy of its gaze, did Navratilova generate broader endorsements. In her case, they came slowly, from car manufacturer Subaru, an unpaid project with Visa Rainbow Card, and, by 2005, deals with gay-focused travel company Olivia, clothing maker Under Armour, and Juiceman products.

With advertising having reached its own level of maturity, to succeed in that field, tennis players had to be what marketers valued most of all: iconography packaged in pre-chewed, acceptable form. The likes of King and Newcombe had sought to establish a beachhead for tennis on the cultural landscape. But from the ’80s on, tennis had grown enough that its players were already well-known and in large part could be brands in their own right. “A celebrity can add almost instant style, atmosphere, feeling,” wrote Lois.

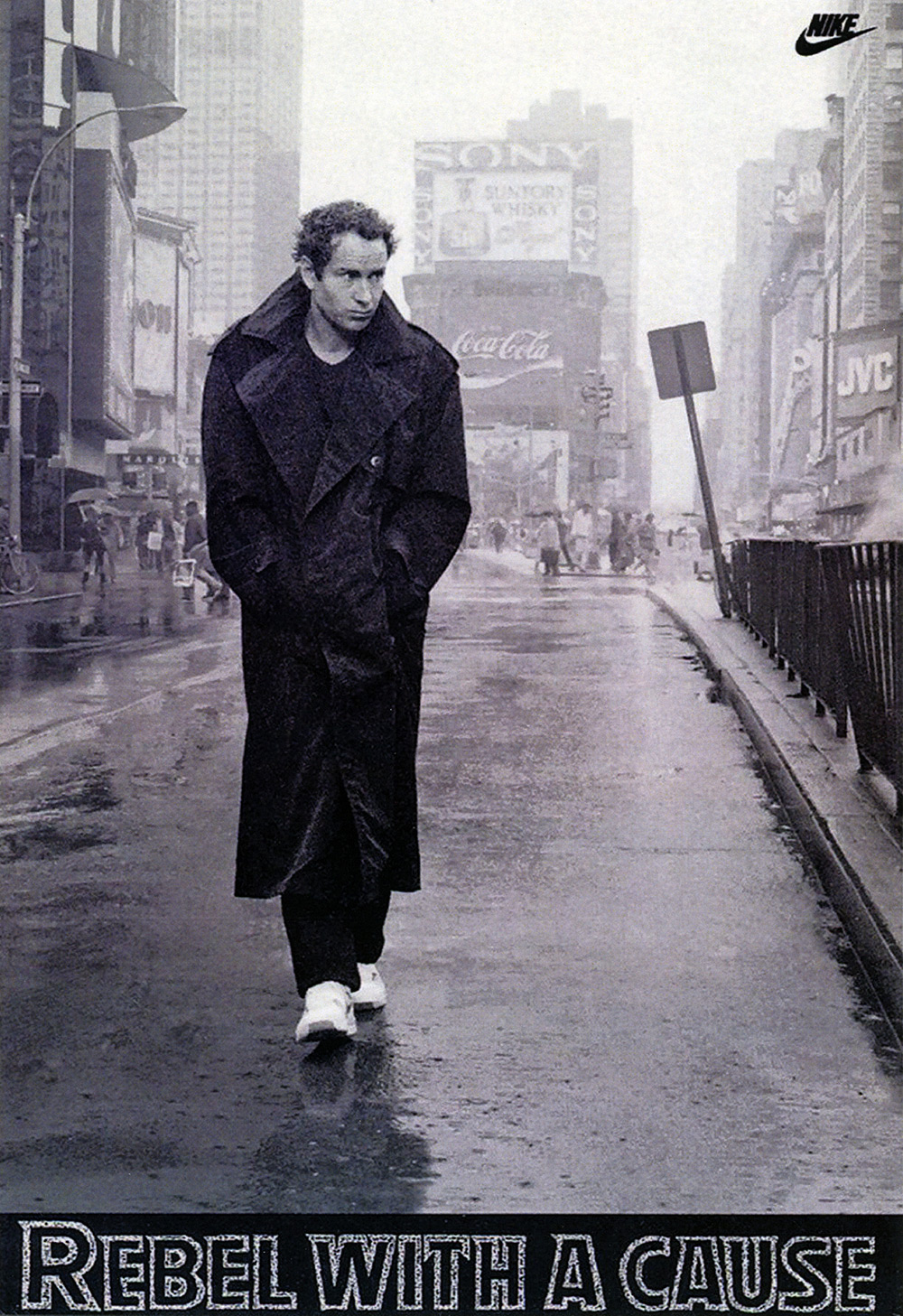

Few mastered this better than John McEnroe, son of a Wall Street lawyer, Stanford dropout, millionaire by age 20, dressed up in a Nike ad trying to summon up memories of Rebel Without a Cause star James Dean. After his playing career ended, McEnroe would adroitly leverage his cantankerous qualities in ads for the likes of automaker Lincoln, candy company Mars, grocery store Tesco, and many others. One expects to invariably see him in a breakfast campaign, shouting, “You cannot be cereal.” Connors, his rough edges largely cauterized by the ’80s, showed off his tenacity in a Paine Webber commercial, his family for Nestlé candy bars, and, later, his enduring grit and bubbling anger in spots for Pepsi, pain reliever Nuprin, and hotel chain Comfort Inn. Evert was the quintessential girl next door, most clearly in ads for Lipton iced tea.

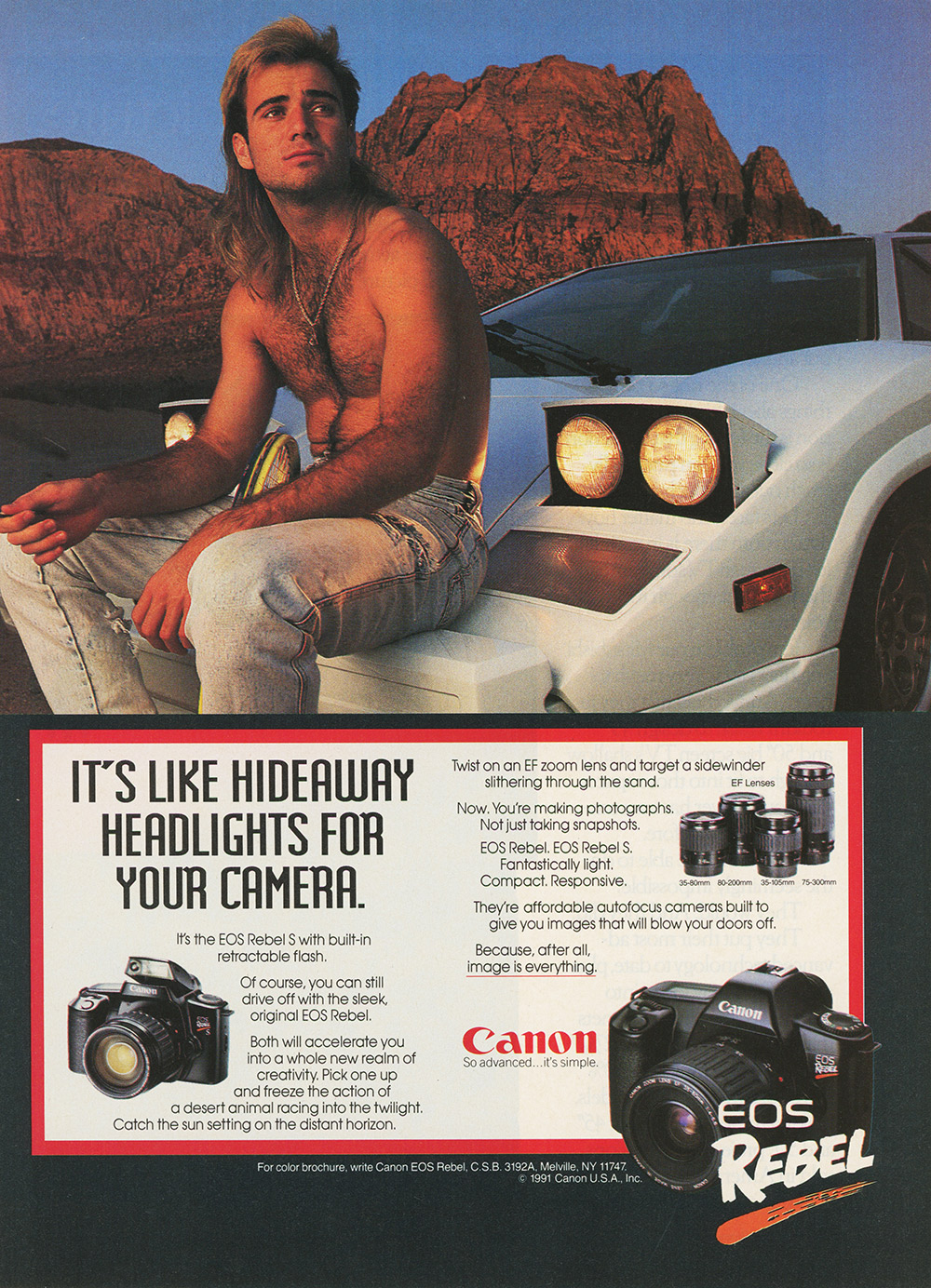

Later came Andre Agassi, Canon’s post-Newcombe avatar. While the Aussie’s ads played off his long success, the yet-Slamless Agassi’s campaign offered promise: “Image is everything,” a tagline he’d eventually regret affiliating himself with at such an early stage of his career. The notion of possibility also played out with the Lolita-like deployment of blond Russian Anna Kournikova in ads for Omega watches and Berlei sports bras (“Only the ball should bounce”).

More in line with the notion that performance will make a tennis player credible to an advertiser, as the Grand Slam trophies swiftly lined his mantel, Roger Federer generated what are now often called “partnerships” with an array of marketers that play off his image as a kind, understated superstar—from Lindor truffle chocolates to Mercedes, Gillette, NetJets, Barilla pasta, and many more. To a great degree, Federer has built off the model Newcombe created: on-court triumphs, plus charm and good looks, add up nicely.

Also in the new century, WTA stars such as Venus Williams, Serena Williams, and Maria Sharapova rapidly generated results that made them compelling spokespersons for a wide range of companies. In addition to their lucrative deals with racquet and apparel manufacturers Wilson, Nike, and Head, each of these three swiftly became major crossover icons. Venus appeared in ads for the likes of Novartis Systane (eye drops), Silk (almond milk), and Tide (detergent). Serena’s portfolio has included Lincoln, Gatorade, and dating site Bumble. Sharapova over the years was featured in ads for Canon, Motorola, and Porsche. These players also created their own companies. Venus and Serena both offered clothing lines, Venus with EleVen, Serena with Aneres. Sharapova ventured into candy with Sugarpova.

The late-blooming success of Li Na—2011 Roland-Garros champion at the age of 29—turned a mildly successful player into a multimillionaire. So strong was Li’s commercial viability that Nike made a rare exception to its standard exclusivity clause and permitted her to feature a Mercedes logo on her shirt.

Naomi Osaka is the latest commercial juggernaut. A 2019 Forbes article said that “Osaka’s accomplishments, youth, skill and multicultural appeal make her a marketer’s dream.” The piece cited deals she’d signed with Mastercard, All Nippon Airways, Nissan, and Procter & Gamble, as well as her multimillion-dollar equipment contracts with Yonex and Nike.

To think that 50 years ago, Gladys Heldman, King, and eight others had begun their rebellion with a $7,500 tournament. King knew that earning $100,000 would make a major statement—a female tennis player making more money than a great many baseball, football, and basketball players. All that laid the groundwork. According to Forbes, of the world’s 15 highest-paid female athletes, all but three are tennis players. But each of those tennis players also earns at least $1 million a year simply in prize money. While King and her peers were grateful for every additional nickel, now the tables are turned. In an era when credibility is at a premium, advertisers are the ones who need tennis players (at least occasionally).

***

Her knees shot by those years of aerobics, Katharine attempted a return to tennis. But she found pickleball a lot easier. Katharine was struck a few years ago to see how Billie Jean King was once again an advertising darling, appearing in ads for the likes of Merrill Lynch, Nutrisystem, and Geico. The Geico ads were particularly amusing. In one of them, King competes versus the spokesman and the scoreboard reveals he is losing 6–0, 6–0, 5–0. “I get it,” he says. “I quit, but I get it.” In another, she’s his coach. “Don’t be so hard on yourself,” says King. “Just shake it off.” Given all Katharine had been through in her career, it was remarkable to see King giving orders to, of all people, a caveman.

Joel Drucker is a frequent contributor to Racquet and is a historian-at-large for the International Tennis Hall of Fame.