GETTY IMAGES

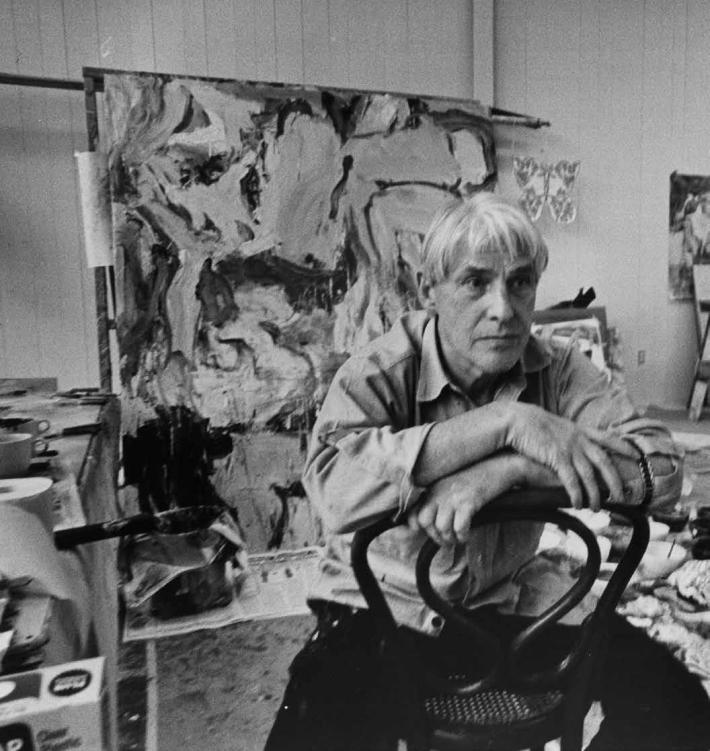

Though Willem de Kooning was distraught after the funeral of his great rival and sometime friend Jackson Pollock, the abstract expressionist painter was reported to have said, “It’s all right. That’s enough. I saw Jackson in his grave. And he’s dead. It’s over. I’m number one.”

De Kooning might have believed that he really was “number one,” but reality eventually caught up with him. Pollock—who suffered from alcoholism, depression, and general emotional instability—met his end when he plowed his car into a tree, killing himself and a passenger. His girlfriend, Ruth Kligman, survived the crash, and within a year started an affair with de Kooning. Kligman dated de Kooning for several years, but had spent only a couple of months with Pollock. Nevertheless, she reported in her book Love Affair: A Memoir of Jackson Pollock—whose title and subject matter must have gnawed at de Kooning—that de Kooning “never stopped being jealous of Jackson even long after he was dead.”

These details and more are revealed by Sebastian Smee, the Australian Pulitzer Prize-winning art critic, in his brilliant The Art of Rivalry (Random House, 2016), in which he shines a light on the complicated relationships that play out in professional rivalries through the example of four pairs of modern artists—de Kooning and Pollock among them. He deftly manages to work out not just the fundamental differences but also the commonalities that build the foundation of any fruitful rivalry.

What initially strikes spectators are the overt opposites that define the best rivalries of any kind, be it in arts or sport or politics. De Kooning, for example, was a virtuosic draftsman who could hold his ground with anybody, and in this regard was often compared to the Neoclassicist French painter Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres. Pollock, on the other hand, always struggled with the technical aspects of painting, delivering clumsy drawings that lacked the quality of even his peers at art school.

At first, de Kooning was stuck in his own head, struggling to establish an original style and grappling with his own ideas of artistic authenticity. This kept him from claiming renown beyond his peers in New York City and applying his virtuosity to the inventive, free-spirited, boldly colored canvases he was later renowned for. For years, de Kooning couldn’t break free from this self-inflicted blockage in his process. He needed somebody else to pave the way for him.

That somebody else was Jackson Pollock. He might have lacked de Kooning’s draftsmanship, but he managed to own his weaknesses and transform them into strengths. His now-famous drip paintings were not only a breakthrough in modern art, heralding the abstract expressionist movement, but also a conquering of one’s own assumed limitations, indeed a means of using them to make art that was wholly new and original. The real moment of rivalry between the two painters occurred in 1948 when de Kooning showed his so-called “black paintings,” which seemed to channel the drip technique of Pollock that he had debuted the previous year.

Artists in their work space are fundamentally lonely people. They might have assistants and advisers and galleries supporting them, but deep down they know that each moment in the process bears countless possibilities. Each decision taken toward a yet unknown outcome could yield results that might or might not be successful, mercilessly laying responsibility at the feet of the artist and nobody else.

This is as true for tennis players as it is for artists. Tennis players have a support system too, in their coaches, trainers, and managers, but in the end they are deeply alone on the court. This is a feeling unlike any other human emotion I know, one that strangely leaves one feeling abandoned and lonely but also strangely empowered. Triumphant moments of overcoming flashes of weakness to emerge as a presumed better self because who can really say what it means to be a “better” you?—alternate with succumbing in similar moments, leaving behind a desperate internal struggle.

A struggle is a struggle, though, and migrating it from internal to external can help protect a delicate sense of carefully crafted sporting identity that is constantly assaulted by failures—in my case, losses on the tennis court that, the way our sport is structured, could occur almost every single week of your life, even amid an otherwise successful career.

Rivals can be an outlet for that struggle, a target for refocusing energy on something other than one’s self. A defense mechanism against succumbing to self-doubt.

The most sublime rivalry in the tennis world over the past decade—and my all-time favorite—is the one between Roger Federer and Rafael Nadal. Their epic struggle for supremacy is befitting a Hollywood epic and has shown us tennis fans the epitome of opposition, culminating, for the time being, in this year’s spectacular Australian Open final (though we all hope there are more chapters to be written).

On one side is the Swiss master, Roger Federer, who never seems to shed a drop of sweat on the court, looking elegant in even the most physically demanding moments and generally making everything look easy, his movements flowing from a never-ceasing well of talent and artistic simplicity. Opposite him is the Bull, Rafael Nadal, who makes even the easiest shots look like what they really are in their ultimate raw nature: hard work put in day in, day out over years and years of disciplined training. He seems to be fighting for his life out there, rendering urgency to each and every point. Nike craftily exploited their differences, dressing Federer in polo shirts and muted colors while giving Nadal sleeveless shirts that showed of his muscular physique, coming up with new bold colors every Grand Slam and henceforth contributing to the overall perception of opposition, despite the fact that the two men have nearly identical physiques: the same height, weight, and wingspan.

What makes the nature of a rivalry’s relationship so tricky is that the main people concerned are not necessarily aware that they are in the middle of one until the outside world points it out to them.

Talk of these contrasts was all the rage around tennis, years before Andy Murray and Novak Djokovic disrupted the hierarchy, but tennis writers and fans alike seemed to overlook Federer and Nadal’s similarities, so grand were the differences. They both seemed to thrive in adversity, almost physically growing in the most stressful moments in their matches. An insatiable hunger for more wins and a seemingly never-ending motivation to force themselves to raise their games during the greatest of challenges were emblematic of their mental fortitude. During these moments, fans (and us colleagues) could pick up an almost visible narrowing of their thought processes when they were in the latter stages of a tight match.

It almost seemed as if the inner part of their games was very much like what they projected to the audience. Their rivalry, at its height, seemed to have a language of its own. Was it the same for Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning? Who knows? The fact of the matter is that both were fragile personalities prone to alcoholism and drug abuse, hypersensitive souls that couldn’t cope with the fame that eventually hit both of them with the force of a rocket. Unlike Federer and Nadal, when they achieved renown, they were even less prepared to cope with it, and even less so when their fame began to recede, slipping through their fingers while they were still trying to figure out how to deal with their newfound standing.

As in tennis, there’s always someone looming on the horizon. Ironically, de Kooning, with his newfound visual prowess and the rise of the Pop artists, was partly responsible for Jackson Pollock’s downfall. Later the minimalists were the ones to undermine de Kooning.

What makes the nature of a rivalry’s relationship so tricky is that the main people concerned are not necessarily aware that they are in the middle of one until the outside world, generally in the form of the media, points it out to them. Even though we had played side by side for almost 10 years, when Angelique Kerber—a good friend, fellow German, and current No. 1-ranked player in the world—started winning Grand Slams, I was made to understand that we had an active rivalry going.

After Angie had won her first Slam (the first German to do so since Steffi Graf), we participated in a pre-draw Fed Cup press conference in Leipzig, an event to which normally less than five people show up. This time the room was packed. All the questions were directed toward Angie, who, though she has gotten much better with the press, has never really felt a hundred percent comfortable in their glare. At the very end of the news conference, when a reporter asked me how the situation had changed for the whole team, I cracked a joke. The entire room laughed and that was that, the press conference was over. Leaving the room next to me, Angie turned my way and said, “I’ll never be as good with the press as you are. It’s just not my thing.”

It was perplexing to me that this was going through her mind after just winning her first Grand Slam and having all the positive attention on herself for the first time in her career.

This made me examine our relationship. I realized that we had our own sort of rivalry going on for years, and I understood how jealous I had always been of Angie’s ability to adapt to any kind of condition, be it wind or fast courts or new balls—not so much her results, but more the essence of them. She always seemed to be so much more talented than me, reading the game better, seeing spaces on the other half of the court I never even realized were there, and even being stronger and faster and having more endurance in her matches, while I beat her in almost any off-court activity.

When she said what she said after the press conference in Leipzig, it was as if a gate to her mind opened up for me and I could see right through it. I suddenly knew how she had apparently envied me for my relaxed handling of the press, which had always felt very natural and organic to me. I envied Angie for her confidence as a tennis player and athlete, while she surely must have envied me for my confidence as a person of the court. And something else became clear to me, being so close to her for so many years: The moment she had found that confidence as a person and a woman in herself, she started having the results I always knew she had in her.

I don’t think we envy people—and I think this is true for athletes, artists, whomever— for what they seem to have and we don’t. We envy people when they make the most of their own assets and limitations while we struggle to make the most of our own character traits. It’s time for me to find my confidence as a tennis player, a part of my personality I have always doubted. Fortunately, I have the perfect inspiration right in front of me. And unlike de Kooning and Pollock, Angie and I aren’t going to destroy each other.

Andrea Petkovic is a professional tennis player.

Featured in Racquet Issue No. 3