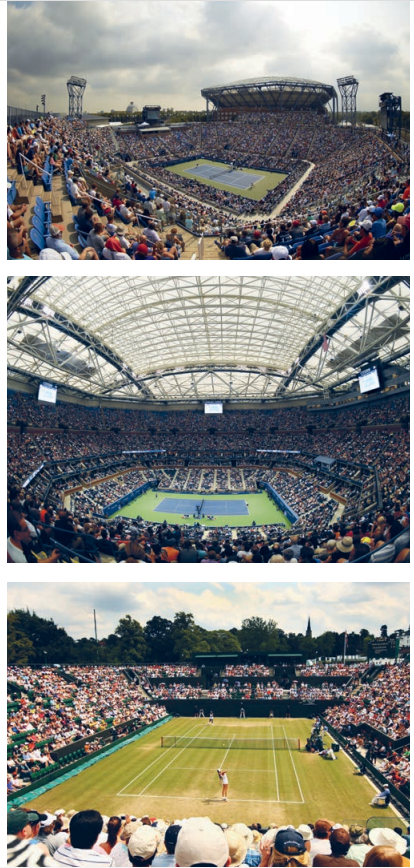

It was right about the time Marcel Granollers approached the umpire’s chair that I vowed never to set foot in Arthur Ashe Stadium again. Granollers, it was easy enough to surmise, was annoyed by the noise in Ashe: the noise amplified to the skies, as it were, by the new, $150 million retractable roof now closed high above him and his opponent, Andy Murray; the noise comprising downpour thud and Long Island Railroad rumble and upper-tier attendee chatter, the latter noise growing ever louder to be heard over the roof-trapped noise, making it all but impossible, Granollers would later say, to “feel” the game. Which, I guess, was a lovely Mediterranean way of saying he could not concentrate. From my press seat at the top of the lower promenade, I couldn’t concentrate either.

It would have been hard enough with the roof open: a second-round match on a dreary Thursday between a man soon enough to become world No. 1 and an unseeded, aging Spanish journeyman, a match in no way meant for a cavernous stadium that holds more than 22,000, the largest tennis venue on earth. (It would be over, in Murray’s favor, quickly enough: 6–4, 6–1, 6–4.) In truth, I’d only gone into Ashe, a venue I’ve never liked, to get my own feel for the new roof, which had had its maiden closing just the night before. It felt awful.

Which set me to thinking: For those of us who attend and really watch matches, which tennis arenas do feel right? Everyone, of course, has her or his favorite or two or three, choices shaped my matches savored and who we watched with, by mood, weather, even time of day. Me, I have a particular thing for tennis as twilight approaches—because I think those seated around me are the fervid fans, still quietly attentive at day’s end; and because the light can be so soft and fine. When, say, on just the right midsummer evening, I’m watching a match from up high in the newish No. 2 Court at Wimbledon, with a crepuscular toning to the green, green grass below me and a view up and beyond, toward town, of the old St. Mary’s Church, its spire rising into a sky swept by clouds purpled and backlit orange—a Constable sky—I am precisely where I want to be.

Court 2 at Wimbledon has something else. It is a stadium, albeit a smallish one, able to seat only around 4,000. That’s the sort of size to allow for intimate tennis-watching from nearly any seat and yet provide you the sense of spectacle you are seeking when you turn off your TV or laptop stream and head out to watch tennis live. The new Grandstand Stadium in Flushing seats twice that many, but to me does the same trick, even better. The bowl shape makes for great sight lines. It’s a relief to be able to get up from time to time and watch standing from beneath the shade canopy that encircles twothirds of the top of the stadium. And from a veranda up there, you can view the action on adjacent courts. One late afternoon last summer near the Open’s end, watching Jamie Murray and Bruno Soares defeat Nicolas Mahut and Pierre-Hugues Herbert in a hardfought, three-set doubles semifinal, the light falling and shadows lengthening, the crowd growing with every changeover during set 3, I scribbled in my notebook: “This stadium was built with us in mind.”

So why hasn’t that been the case more often? Or even more occasionally? Why does the fan experience seem, so commonly, to be an afterthought of those designing and building pro tennis arenas?

In the case of the US Open’s Louis Armstrong Stadium, tennis was never a thought when it was constructed—that is, constructed as the Singer Bowl for the 1964 New York World’s Fair. I have a vague memory of a Count Basie concert there that my parents dragged me to, and no fond memories of the tennis stadium it became in 1978, notwithstanding the many great matches it hosted. I did have a thing (who didn’t?) for the old Grandstand, the third of the Singer Bowl that got lopped off and turned into a singular hardcourt bandbox. There’s a new 14,000seat Armstrong scheduled to open next year, with a retractable roof. We’ll see.

Fifteen thousand—the seating capacity of Centre Court at Wimbledon—is about as big as a tennis stadium can get and still offer every spectator a seat from which to have a meaningful viewing experience. Stadiums bigger than that—for football, baseball, soccer—offer fans the chance to join with other fans. Singing a player’s name, yelling the old school chant, you are swept up by rooting with others, creating a bond with the crowd. Unless you are at a Davis Cup or Fed Cup match, that isn’t tennis. With tennis, you might join others in cheering for a deciding set, or encouraging an underdog. Mostly you sit in silence, watch attentively, and hope for great tennis.

So when the next main stadium is built wherever, it should be made smaller. Shortly before it opened in Singapore in 2014, I took a hard-hat tour of the National Stadium, and the CEO of the multipurpose sports complex of which the stadium was to be the centerpiece, Philippe Collin Delavaud, demonstrated for me its “configurable” spectator tiers: 55,000 for soccer, a tenth less than that for other sports, the lowest tier retracting. How about something like that for big show courts: fewer seats until the quarterfinals?

The National Stadium in Singapore also has an energy-efficient cooling system that delivers chilled air to every seat. Imagine that for midday matches. Or how about seat backs that deliver real-time data on the match you are watching? What true fan wouldn’t rather have that than a Jumbotron? Anyone with a smartphone knows the technology is available. And imagine if stadium courts were outfitted not only with HawkEye, but with the smart-court technology underpinning PlaySight? Watching would deepen.

Finally, let’s invite our best, most creative architects to stretch our sense of the possible. Yes, main stadiums have constraints: They have to move a lot of people in and out quickly and safely; there are the needs of vendors; there’s the need to extract money from sponsors who want suites where they can entertain clients and bibulously ignore the match. But architects, the great ones, understand this, and still manage to inspire. Think of the Allianz Arena, designed for the football club Bayern Munich by the acclaimed Swiss team of Herzog & de Meuron, with its spectacular color-changing facade and procession-like approach that delivers fans, together, to the team they worship. Think of the beautifully wavy, undulating design Zaha Hadid conjured for the London Aquatics Centre at the 2012 Olympics.

Tennis is the most artful of sports. Let’s house the art better.

Gerald Marzorati is the author of Late to the Ball, a memoir about tennis and aging. He writes about tennis regularly for The New Yorker’s website.

Featured in Racquet Issue No. 4