Bayanihan, a Filipino term that embodies community spirit, unity, and cooperation, finds an unexpected home in the tennis courts of the Philippines. In a country with limited access to tennis facilities and equipment, the tennis community I experienced there radiate s with it. I found myself in the Philippines for the first time after visiting Melbourne for the Australian Open in the beginning of 2024. I was backpacking across Asia for a month and I found myself in the Philippines again because a friend was visiting her family there, and tennis became my key to Cebu City.

In the heart of Cebu exists a tennis oasis called Asmara Urban Resort & Lifestyle Village. The use of locally - sourced materials, such as volcanic rock, bamboo, and banana trees, combined with extens ive greenery, makes you forget you’re in the second largest city in the Philippines. The owner, Carlo Cordaro, is an Ethiopian - born Italian expat who fell in love with Cebu 25 years ago and never left. Designed and constructed himself, Carlo also takes pri de in bringing cocktail culture to Cebu through their Gravity Cocktail Lounge, which attracts locals and tourists alike. An artistic and functional centerpiece to the resort is a two - story inverted pyramid, built into the structure, designed to capture rai nfall. All of which overlooks three impeccable tennis courts, named Rome, Paris, and Monte Carlo: home to the Asmara Open.

For the past few years, Asmara has hosted the Asmara Open, which has grown to include a qualifiers draw, welcoming a broader range of participants. The 2024 Open was the first time the tournament would be officially sanctioned by the Philippine Tennis Association, or PHILTA, and it had earned the highest grading — Grade 1 — awarding national ranking points.

The Open attracts the top two players in the Philippines, AJ Lim and Jed Olivarez. AJ was ranked 12 in the world in juniors, currently sitting at 1210 in the ATP, and Jed played D1 college tennis in the States at WMU. It has grown to include a qualifiers draw, welcoming a broader rang e of participants. When Carlo told me the next tournament was coming up in November, I knew I had to find a way to make it back and enter it myself. I hopped on a 16 hour flight direct to Hong Kong, hiked a mile across the massive airport, and boarded a ti ny plane that would finish the journey to Cebu. After nearly 24 hours of travel time, with a 12 - hour time difference, I arrived and was informed that I’d play my first - round qualifying match on the very day I landed.

I won handily against Mikel, who had also arrived that same day from San Francisco and was in the country both to play tennis but also for his microfinancing service, which plays a crucial role in the lives of many Filipinos. With most of the population lacking credit history or even a bank a ccount, loans for essentials like homes, cars, weddings, or medical emergencies are often out of Asmara Open Final.docx reach. Mikel’s service operates similarly to a pawn shop, offering cash advances using gold, jewelry, and other valuables as collateral. I lost the second ma tch against Miguel, a local coach, dashing my hopes for a deep run at the Asmara Open. After a moment to sulk, and a surprise press conference, it was time to explore and watch the rest of the tournament from the stands.

Given the tropical climate of the Philippines, we were quite lucky to experience minimal rain during the tournament. But one afternoon, a massive rain cloud rolled in and unleashed a flash storm. Within minutes, the courts were submerged, and it felt like tennis might be canceled for the r est of the day. However as soon as the downpour stopped, bayanihan kicked in and all hands were on deck. The ballpeople, tournament directors, and even a few spectators jumped onto the courts with one goal in mind: to get them dry and playable as quickly as possible.

Armed with large sponges, a dozen or so people got on their hands and knees to soak up the water — most of the ball people worked barefoot, their toes gripping the slippery surface as they squeezed out the sponges into buckets or drains. It was sweaty, muddy work – the Asmara courts are built of local river mud* – but there was a strong sense of camaraderie as everyone pitched in. Being barefoot wasn’t just practical — it was a symbolic embrace of the grit and resilience needed to keep the tournament going.

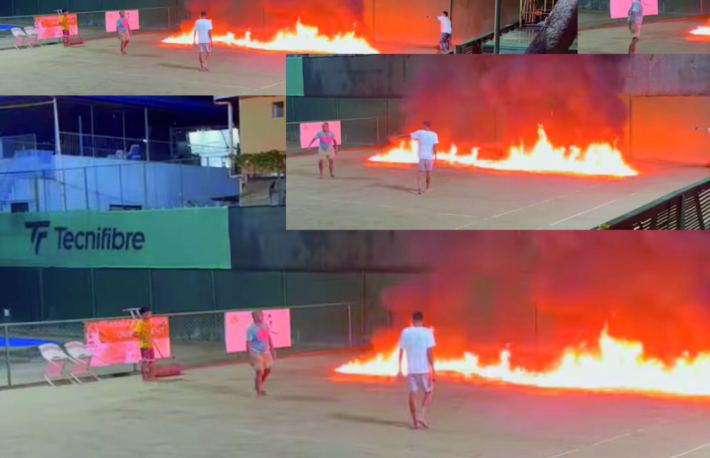

Of course, this year’s rain delay wasn’t the first time the Asmara Open faced such challenges. Last year, during the finals, rain had struck at the worst possible moment, threatening to delay the championship match indefinitely. With the players s cheduled to catch flights that evening for their next tournament, there was no time to spare. Desperate to dry the courts, Carlo poured gasoline onto the water and set it on fire. It worked; the gasoline burned off quickly, evaporating much of the water in the process. The remaining moisture was soaked up with sponges, and the surface was leveled with a hand roller. Against all odds, the courts were restored in time to finish the match.

Adam Borak is a tennis player from Brooklyn, NY and the founder of theTipsy Tennis Podcast.