An Art Critic Finds Unlikely Inspiration in Angelique Kerber’s Breakthrough Year.

By Tyler Green

Illustration by Johanna Goodman

The last thing I did before going to bed on January 29, 2016, was set up my computer for the next morning. I closed Twitter, all my browser tabs, and all my notifications. I opened ESPN3 in a new browser window and went to the page where I could stream the replay of the Australian Open women’s final without knowing who won. I memorized where ESPN3’s play button was so that when I woke up the next morning, I could cover up the rest of the screen with a piece of cardboard while clicking it. The match I wanted to watch, Angelique Kerber vs. Serena Williams, would start at 3:30 in the morning. My plan was to wake up at my usual time, around six, turn on my computer, and stream the match without knowing who won.

As I lay in bed, awake, for hours, eager for morning, I realized that two weeks of overwhelming pleasure were about to come to an end—and that I was making a fairly routine sporting event into what felt like the most important thing in my life, the determinant of my happiness, the only thing that mattered. What was wrong with me?

The previous few months had been frustrating, even difficult. I had been trying to write a book, a biography of Carleton Watkins, the greatest American photographer of the 19th century and the most influential American artist of his time. Today Watkins is best known for a series of pictures he made of Yosemite Valley and the nearby Mariposa Grove of giant sequoias at the outset of the Civil War, in 1861. Those pictures helped bind the wavering West to the Union and motivated Congress and President Abraham Lincoln to do something no government anywhere in the world had done before: preserve a landscape in perpetuity. Such is Watkins’ status that the last retrospective of his work traveled to three of the most important museums in America: SFMOMA, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the National Gallery of Art.

This book project was a stretch for me. My professional background is in journalism, as an art critic. I’d had a nice little career. I wasn’t the critic for a big newspaper or anything—I’d applied for a few of those jobs but hadn’t gotten them—but I created the first blog about art, had become an art-magazine columnist, and edited a website that was reasonably well-read within the art world. In 2014, 13 years into my art-journalism career, my peers voted me an award. As I had come to art accidentally after having been a sportswriter and working in social justice, winning an award made me feel like I belonged.

Now I was having a hard time figuring out how to do the thing. As a critic I wrote 800to 1,000-word reviews of exhibitions; now I was inventing a 180,000-word manuscript that spanned 90 years of American history, from my artist’s birth a few years after the Erie Canal was completed until his death in the automobile age. My manuscript was due to my publisher, University of California Press, at the end of the year. I was way behind. A few months earlier I’d started writing six days a week. It often seemed like I was spending Friday and Saturday stuck in the same problems I’d had on Monday and Tuesday.

I recognized my morass enough to know that watching tennis for a couple weeks might help me clear my head. While I’d never written a book before, dropping everything to watch Grand Slam tennis tournaments was familiar territory.

Within a few days I found myself caught up in Angelique Kerber’s matches. Like every tennis hipster I knew, I enjoyed watching Kerber play but had never quite considered myself an all-in fan. I admired the way she didn’t just track down every ball her opponent hit, but invented angles while on the run, going from last-gasp defense to howdid-she-hit-that winner in nothing flat. Most aesthetically pleasing of all was Kerber’s down-the-line, lefty forehand, one of the best shots in the sport. A bunch of recent Kerber matches were among my favorites of all time: Her 2015 Charleston final win over Madison Keys was a classic of the big-hitter vs. counterpuncher genre; her 2015 Stanford quarterfinal win against Aga Radwanska was a classic of the crafty, quirky chase-it-alldown veteran vs. crafty, quirky chase-it-alldown veteran genre; and her 2015 US Open third-round loss to Victoria Azarenka was the best match of that tournament.

Winning two of those three matches, even at the WTA's middle level, was a big step forward for Kerber, who had rarely had enough power or aggressiveness (or belief?)

Like every tennis hipster I knew, I enjoyed watching Kerber play but had never quite considered myself an all-in fan.

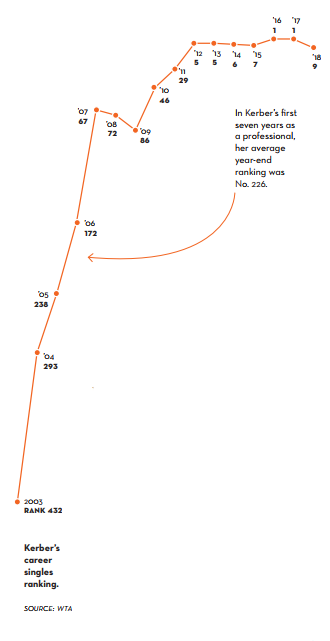

to beat top players on the weekend. Given Kerber’s career history, maybe there was no dishonor in that: In Kerber’s first seven years as a professional, her average yearend ranking was No. 226. (Serena Williams’ average year-end ranking over her first seven years was No. 20.) Even in early 2016, Kerber still had more titles at tennis’ minor-league ITF level than she did on the WTA tour. It was only in 2015 that Kerber had her mini-breakthrough, winning four mid-level

WTA Premier tournaments. Still, Kerber never seemed to do much at the majors. While she had reached a US Open semifinal out of nowhere in 2011, she matched that result just once in her next

16 tries. Kerber’s first match in Melbourne portended more of the same. It was

against Misaki Doi; Kerber needed to save a match point before pulling it out. From there, everything changed. In the next few rounds she steamrolled lower-tier players such as Alexandra Dulgheru, Madison Brengle, and Annika Beck. That put her in the quarterfinals against Azarenka. Just a couple weeks earlier, Azarenka had destroyed Kerber 6–3, 6–1 in the final of Brisbane, running her career record against Kerber to 6–0. Naturally I thought Azarenka would win again, and go on to play Serena Williams in the final.

Nope. This time, finally, Kerber won. That put her in just the third major semifinal of her 13-year career, where she easily handled an on-the-rise Johanna Konta, 7–5, 6–2. Suddenly Angelique Kerber, a pretty good player but rarely a threat to the game’s elite, was in the final of the Australian Open. Against Serena.

img

Obviously I realized that Kerber, playing in her first major final, was not going to beat the greatest player in history. Still, the matchup was a tennis nerd’s delight: Serena, the ultimate power player, against Kerber, the game’s cleverest backboard. This is when I set up my laptop with care.

The two players traded breaks early. From 3–3 Kerber coasted to a 6–4 first set, mostly because Serena came to net too much, allowing Kerber to take advantage by flinging balls past her. Serena took the second set, 6–3. Surely Serena wouldn’t keep coming to net in the third, right? Surely she’d stop allowing Kerber to put her in weird parts of the court to hit shots she wasn’t accustomed to hitting, right? Nope. Kerber kept on tracking down everything, making the 34-year-old Serena run and run and run, and raced out to a 5–2 lead. Could it be?

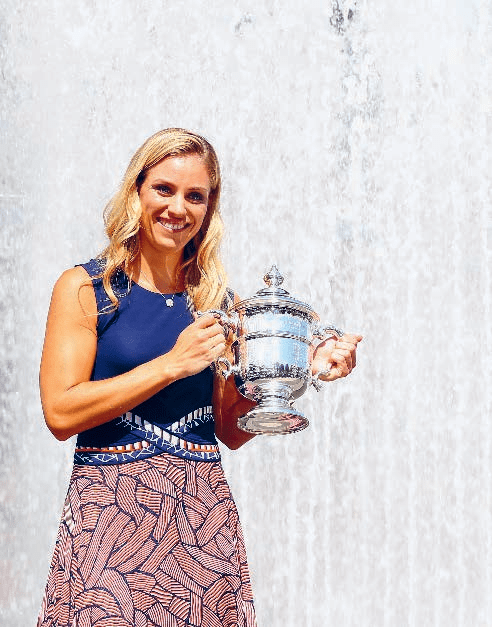

At 5–3, Kerber served for the championship. Serena broke her to 4–5, and would serve to stay in the match. The rallies throughout the game were long and physical, and sent both players scrambling from sideline to sideline to sideline. I had noticed that for a few games now, Serena had been making tired errors at the end of many of these rallies. I thought to myself, if Kerber can keep tracking balls down, can keep making Serena move and work, Serena’s going to break down. Then, on Kerber’s first break point in that 4–5 game, on championship point, Serena came to net when she shouldn’t have and hit a tired volley long. Kerber fell to the ground, her arms outstretched, her body convulsing in surprise or joy or both, a major champion.

I shook too. When tears made it hard for me to see what was happening on my screen, I wiped them away with the backs of my hands.

I cried as Serena walked across the net to congratulate Kerber, and I cried because Serena laughed and smiled through the trophy presentation, somehow looking like she really was happy for Kerber. By now my hands were too wet to do much good, so I mopped up tears with my shirt. I cried some more as Kerber mostly talked about Serena and how much she liked the AO tournament director, at which point I realized that Kerber was going on and on about anything at all, just to avoid having to talk about herself. Finally: “I took my chance to be here in the final, to play against Serena. I’m really honored to be here in the final, and to win it. I mean, my dream came true tonight, this night,” at which point Kerber had to pause to breathe, which gave her emotions an opportunity to overwhelm her, and they did. Kerber bit her lower lip, hard, and covered her face with her right hand. The crowd cheered long enough to help Kerber recover.

The crowd did not help me recover. After having spent months in a book-addled stupor, suddenly I couldn’t hold still. I live-tweetstormed about the match as if it had just ended (“ANGIE! ANGIE! ANGIE! KERBS! KERBS! KERBS!”). I tweeted everything I could think of, from obscure details (“Other big key: Kerbs made Serena serve for the second set, which meant Kerber got to serve first in the third. Gave her chances from 5–x”) to service statistics (“Angie won 47% of her second-serve points, a higher percentage than Serena”). I called up the websites of the big German newspapers and magazines and tweeted their front pages. I retweeted Kerber compatriot Andrea Petkovic’s proud Instagram post congratulating her friend. Then I watched as Petko “liked” my Kerber tweets, including one from the Die Welt website in which a smiling, clapping Serena looks like she believes what had just happened a lot more than the trophy-holding Kerber. “I was going to work this morning. I have no earthly idea how I can focus on the 19th-century American West after KERBS KERBS KERBS,” I tweeted. That gave me an excuse not to focus on the West, so I watched the match again. And when Tennis Channel replayed the match that night, I watched it a third time. Exhausted, I happy-cried myself to sleep.

The next day I tried to understand what had happened (and I don’t mean the match). While on a walk through Washington’s Rock Creek Park I figured it out: Kerber had been a nobody, then she made herself into a pretty good somebody—and in so doing had made a nice little career for herself. Now, out of nowhere, she’d won a Grand Slam tournament. No one—no one—had expected that. I realized that Kerber had transformed me into a semi-ambulatory puddle because I had found in her what I desperately wanted to find in myself: a progression from having been pretty good to having done something significant. Like Kerber, I had never been a major factor, but I wanted to be.

With the Australian Open over, I went back to Watkins. Words began to cohere. When I would hit a lull, I would watch the Angie-Serena replay on ESPN3. (By now we were all on a first-name basis.) When ESPN3 took down the match, I watched a YouTube replay with Russian commentators. Little by little, chapter after chapter, the book began to come together.

Angie’s career arc continued upward. In June she made the final of Wimbledon, where she lost to Serena. Then she made the Olympics final, losing to a peaking Monica Puig. From Rio, Angie went to Cincinnati to play the last big tune-up before the US Open. As I often did, I went to Cincy too. Before leaving, I printed out the 140,000 words I’d written to that point. Each morning I arrived at the tournament site just after the gates opened, sat down in the shade, and read and edited what I had written. When the matches started, I put work away and cheered on Angie (and my other faves). Somehow, despite a 5,000-mile flight, Angie made the final before running out of gas against young, up-and-coming big hitter Karolina Pliskova. By the end of the week in Cincinnati I’d read everything I’d written. I began to feel like I had the book well in hand, that I was going to pull it off.

After Cincy: the US Open. Angie was not the favorite. Serena was. They seemed sure to meet in their third major final of 2016 until Pliskova upset Serena in their semifinal to set up a rematch against Angie for the title.

As in Australia, Angie won the first set. As in Australia, she lost the second. In the third set, with Pliskova serving down 4–5, needing to hold to stay in the tournament, Angie broke her at love to win her second major. I smiled, clapped, and enjoyed the players’ post-match speeches. Then I stood up and cooked myself dinner.

Tyler Green is the author of Carleton Watkins: Making the West American. which will be published by University of California Press in October 2018. He is also the producer and host of the weekly Modern Art Notes Podcast, America’s most popular audio program about art.

Featured in Racquet Issue No. 6