Photos by Geoffrey Knott

The city of New York. How do you even start to pin it down? It’s like a jungle poem, like Scranton on acid, like dating a comedian—these are search suggestions I received from Google when I typed in “Living in New York City is like…” So maybe it’s no longer a muggers’ Eden, or a public graffiti museum—statistically you’re still more likely to be bitten by a rat in the Big Apple than a shark in Florida—but it’s still the greatest show on Earth, having earned prestige through live events, Broadway, the Yankees, the New York Philharmonic. Historically it’s America’s center of ambition, home to its most prestigious venues, as well as the big-name performers who risk it all nightly on behalf of the well-heeled, the well-educated, the fashionable. Entertainment in New York isn’t just impressive, it’s important. And that’s just showbiz.

New York is everything, good and bad. In 1789, it was the United States’ first capital; in 1905, home to the country’s first pizzeria; in 1946, birthplace to the train wreck that is our 45th president. The five boroughs, named for Kings and Queens, not only constitute America’s most populous city, but contain one of the planet’s densest hubs of riches—79 billionaires, the most in the world—plus what’s probably Earth’s most expensive cup of coffee ($18, Extraction Lab, in Brooklyn). The point is, New York has too many significant achievements, too many oddities, just a lot of meaningful stuff in approximately 305 square miles that other cities simply don’t have the history or ability to claim.

But the best American tennis tournament isn’t one of them.

That honor resides more than 2,000 miles to the west, in the sand. Where the spiritual capital is Los Angeles, our greatest strip mall, home to (bad) theater, (decent) sports, and (pretty good) music—all of which, when it comes to entertainment, are merely second-class citizens in a factory town that, for roughly a hundred years, has mostly cranked out a single widget: filmed junk for the global lizard brain. But these days Los Angeles is booming, television is high art. This isn’t the ’70s anymore, the millennials don’t tell Annie Hall jokes, nobody thinks Southern California is a wasteland of stoner morons. (We’re all stoner morons now.) Today it’s hipper and more affordable, even more sensible, to live in Pasadena than Brooklyn—no concerns about rising sea levels, and who doesn’t want an avocado tree?—plus Indian Wells, a.k.a. the BNP Paribas Open, is hardly an Angeleno anyway, less a product of Los Angeles than Palm Desert, the sprawling weirdness of Palm Springs—those desert acres empty enough to accommodate a stop for “The World’s Biggest Dinosaurs,” which includes a creationist museum.

Out in the Coachella Valley, snowy mountains line the horizon, green lawns unfurl forever, the streets crawl with sun-broiled lizard women, gargoyle men and the hairpieces that wear them home. Think Sinatra on the weekends. Think Elvis on his honeymoon. There’s a resort called the Desert Sun, clothing-optional, that built a “Bridge of Thighs”—to enforce head-to-toe modesty—so that its guests could traverse a major road without distracting drivers. The point is, New York may strive to be important, but Southern California is genuinely weird, full of new money and old Jacuzzis, and though I’ve only been to the desert a handful of times, there’s always a permeating sense, sprinkled on visitors by restaurants’ misting wands, that nearly anything is permissible in the desert because everything, someday, disappears into the sand.

Not, so far, the Indian Wells Masters. It’s an open secret I’ve heard off the cuff and off the record for years from tennis officials, coaches, journalists, professional players, that the US Open pales compared with sunbaked Indian Wells. That if you care to watch live tennis, the West is best. Which is why, in March, I drove to the desert to sound out a theory of mine that’s improbable, dumb, but not patently mistaken, I don’t think: that tennis fans would be better served if America’s Grand Slam lapel pin were worn in California for a couple years.

Tennis tournaments in the United States belong to a nomadic tradition. The Winston-Salem Open used to be the Hamlet Challenge Cup in Long Island. The Atlanta Open started in Indianapolis. The Connecticut Open, formerly of Vermont, formerly of Texas, was once the U.S. Women’s Hardcourt Championships, played mostly in a string of Western cities. Some tournaments buck the mold. The Cincinnati Masters has mostly stayed put since 1899, making it the oldest American tennis tournament to continuously be played in its original city. But the custom is typically move or die. Witness the famed Farmers Classic, a.k.a. the Los Angeles Open—long enfeebled—which finally died in 2012, boxed up, sold, shipped to Bogotá. Currently the saddest event to watch slide is the Miami Open. Once aspiring to be “the fifth Slam,” “the Grand Slam of Latin America,” the tournament on Key Biscayne has been sinking, both geologically and in lawsuits, mostly because the grounds, on a slender island, are tethered to a deep-rooted Florida family opposed to development. IMG, which owns the event, insists it’s going nowhere, but still I hear rumors of Miami’s tennis tradition being schlepped elsewhere, even to South America.

But then there’s Indian Wells.

Nineteen seventy-four. Shortly after Billie Jean King beat Bobby Riggs in the “Battle of the Sexes,” Nixon resigned, the Symbionese Liberation Army kidnapped Patty Hearst, and the Cleveland Indians forfeited a game after their fans turned carnal on 10-cent beer. In the beginning, Indian Wells wasn’t much to look at. It was a fund-raising event in Arizona, a product of boosterism, showmanship, sand.

But soon the tournament moved to California, matured in the desert sun, grew roots. The men’s and women’s tournaments, run separately, came together in the ’90s. Opening in 2000, the Indian Wells Tennis Garden, today’s site, was constructed on 54 acres, with the second-largest outdoor tennis stadium in the world (after Arthur Ashe, in Queens). Still, tempting offers appeared from seducers overseas to move abroad, uproot and rename. Then came a billionaire.

Larry Ellison, cofounder of Oracle, declined to be interviewed for this story. Big surprise, the guy supposedly requires a nondisclosure agreement just to visit his weekend house. A known tennis nut, Ellison dropped a reported $100 million to buy the tournament in 2009 and promptly started an arms race, for facilities, prize money, reputation. Hawk-Eye, the pricey line-spotting system, was installed on every match court—Indian Wells remains the only tournament where that’s true. Winners’ purses got jacked up to over $10 million. In 2013, a second stadium was built, 8,000 seats, with a Nobu branch overlooking the action, to complement the 16,100-seat mother ship, which in turn was overhauled in 2016-17 and gained its own restaurant with a viewing platform, a branch of Wolfgang Puck’s Spago.

I know I said the tournament’s a desert creature, but could it get more L.A.?

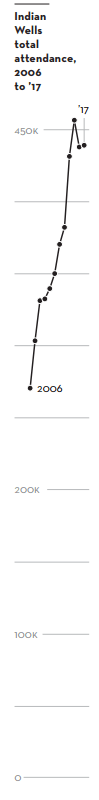

Fancy names and all, something’s working. In 2016, Indian Wells drew 438,058 fans, a 30 percent increase since 2009. Granted, that’s around 300,000 fewer people than went to Melbourne or New York—but also nearly 140,000 more than visited Miami. All the top players turn out, for the most part, if they’re healthy; they even play doubles. This year The New York Times asked the tournament’s chief operating officer, Steve Birdwell, if he was worried about outclassing other tournaments. “You’ve got to run your own race,” Birdwell said. “Again, we’re fortunate to have the owner we have. He’s got some ideas and he’s got a style of his own, and it’s fantastic for us.”

Ellison’s style includes a 249-acre estate in nearby Rancho Mirage. Roger Federer and Novak Djokovic have visited; Tommy Haas has been a houseguest; Rafael Nadal spent the night in a cabana decorated with photographs of his various trophy presentations.

The first time I went to Indian Wells, in 2015, I was surprised by how much I liked it. Growing up in Connecticut, I’d been going to the US Open since I was a kid, and I always came away disappointed. Overpriced, overcrowded, inundated with corporate sponsorship—I might as well have gone to Times Square. Sport never seemed to be the point, but the excuse to pack a bunch of wallet-bearing humans into a confined space. These days, for all its glitz, Indian Wells feels designed with a different purpose: to satisfy people who actually like tennis.

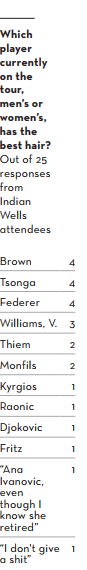

This year, total attendance at the tournament was slightly higher. For two days I wandered the grounds with a clipboard and a stack of surveys, going up to people to chat. What did they like about the tournament compared with the US Open? What did they dislike? How would they feel about Indian Wells becoming a Grand Slam? Twenty-five people consented to fill out my form. They were of many ages and skin colors, ranging from “Team Thiem”—three white guys supporting Dominic Thiem, wearing homemade hats decorated with Mardi Gras beads—to Hispanic father-daughter pairs, African-American foursomes, a young woman from Austria who said she’d traveled the world just to watch Federer. One kid, a tennis nut, had come to California all the way from North Carolina because he’d heard that Indian Wells was the best value in tennis.

To start, what did people like about the tournament? “The tennis.” “The level of the tennis.” “The weather.” “The tennis atmosphere.” “The access to practice courts.” “The practice courts.” “They send the practice court times to your phone.” “Actually I wish they didn’t post the practice courts; you used to have to work harder for it.” “The phone charging stations.” “The grounds.” “The proximity to the players.” “The practice court access—the US Open is still catching up on that front.”

What they didn’t like about Indian Wells was similarly consistent. “The sun.” “The heat.” “The lack of shade.” “The lack of shade in the stadiums.” Also, from several people: “the endless whiteness,” or words to that effect, referring to skin tone. As one African-American woman put it, “We’re in one of the most diverse states, and you really have to work to see any non-white people here.”

Regretfully, this is not a new problem for Indian Wells. In 2015, the organizers scored a tremendous PR coup: Serena Williams returned to play after she’d boycotted the tournament for 13 years—for some nasty crowd behavior, which included racial abuse, according to her father. Charles Pasarell, then the tournament director, told U S A To day that he was “cringing” when the crowd was booing. But the good vibes of Serena’s return were quickly undone the following year when Raymond Moore, a former ATP pro from South Africa and the tournament’s then director, said during a media breakfast that female players today ride on the men’s “coattails,” adding, “If I was a lady player, I’d go down every night on my knees and thank God that Roger Federer and Rafa Nadal were born, because they have carried this sport.”

The backlash was swift. Serena Williams responded pointedly: “We, as women, have come a long way. We shouldn’t have to drop to our knees at any point.” Damage control continues to this day, with at least one positive outcome: The tournament has a new director in the amiable, still boyish, still-occasionally-a-professional-tennis-player Tommy Haas. Moore remains connected to the event, a “consultant to Mr. Ellison,” but nowhere near microphones. I reached out to Haas for commentary: How does he see Indian Wells compared with the Open? Haas replied via email: “We don’t compare ourselves to the US Open or any other tournament. Our goal each and every year is simple—continually improve.” He added, “We execute the vision that Mr. Ellison sets forth, which is focused on the BNP Paribas Open continuing to be one of the greatest international sporting events worldwide.”

Makes you wonder if they’ve also revamped their media training.

Ivan Ljubicic won Indian Wells in 2010, the peak of his career. The Croat beat Djokovic and defending champion Nadal that year on the way to the final, where he triumphed over Andy Roddick, 7–6, 7–6. It was Ljubicic’s first and only Masters Series trophy; he’d previously lost three other Masters finals. “It was probably even sweeter because it was at the end of my career,” he told me. “If you look at past winners here, it’s always top guys. But the fact that guys come here fresh, and have one day between matches—it makes it extra special to be the top.”

Ljubicic is better known these days as Federer’s latest coach, the one who helped construct a time-fuck wormhole so big that Roger, after a six-month absence, could return to the tour and almost instantly beat Nadal in the Australian Open final. Ljubicic and I met in the Indian Wells players’ lounge, a large suite of televisions and couches. I asked him to compare Indian Wells with the Open. He said that when he was player, Indian Wells was his favorite American tournament. “The fans here are coming to watch tennis. They’re not necessarily star-driven.” As for the Open: “It’s ‘The Open.’ The biggest tennis event in the world, they like to say, which I don’t think it is.” He added: “It’s not really player-friendly…. Here, you feel like people are happy you’re here. The US Open, they have security guards who don’t recognize Roger Federer. It’s the only major I know that only has one locker room. Transportation is a headache most of the time. You feel like it’s a machine, not an event custom-made for tennis, the players, or the fans.”

A few days after our chat, Ljubicic’s client would beat Nadal again, on his way to winning Indian Wells, then proceed to win Miami, also against Nadal. The nostalgia was out of control, the fandom was frothing. It would mark Federer’s third career “Sunshine Double,” remarkable especially because Federer hadn’t won Miami since 2006, when he beat, of all people, Ljubicic. When I asked him what about my idea of shipping the Grand Slam epaulets out west, if only for a brief rotation, Ljubicic laughed. “Well, that’s a very aggressive opinion.” He thought about it for a second. “I feel like this city, this valley, lives for tennis. In New York, the US Open is just another big event. Here, you go because you want to see tennis. You don’t end up here by mistake.”

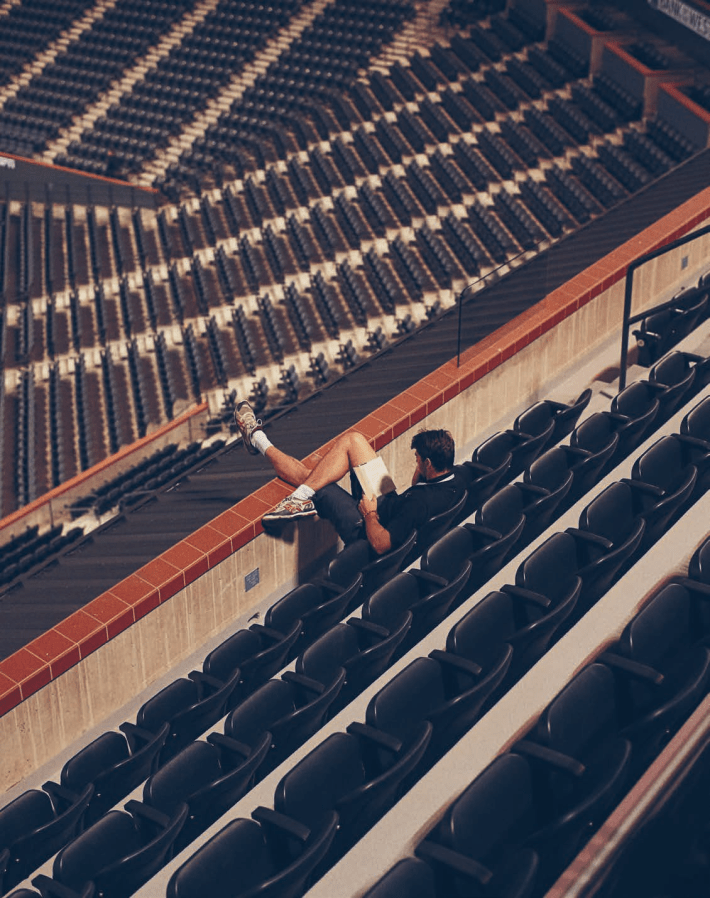

Tennis is a weird sport, particularly on bigger courts. Players demand silence. Fans expect access. It’s We Will Entertain You on Our Terms versus We Will Be Entertained as Long as You Sign Our Big Fuzzy Yellow Balls. Almost 50 years since the sport went pro, an amateur spirit still thrives, at least superficially. Practices are open-access. Fans dress like their heroes. It’s an often-made point that many tennis aficionados wear full match kit to tournaments, as if expecting to be called in to play. My notion is that the more such fans you see at a tournament, the greater indication that the tournament is designed to appeal to diehards. And of the many tournaments I’ve attended, with old and young in court gear, Indian Wells has them all beat.

And that’s the thing: At its worst, the US Open has the style of tennis, not the substance. Great tennis takes place in Queens every year, of course; in the history of American tennis, it’s the spot. Among the classic matches I’ve watched on screen, I love McEnroe’s run in 1980, Evert/Navratilova in 1984, Serena over Azarenka in 2012. But in person, when I go to the Open, the day-to-day too often feels like an American Express-sponsored theme park; I’d rather watch from a bar down the street. Of course, all sport is entertainment, advertising pays the bills. You don’t need to have a Ph.D. in American history to enjoy Hamilton any more than you should recognize the Federer forehand ahead of the logo on his racquet. But Indian Wells, by doing so much to at least seem to cater to knowledgeable tennis fans— with easier access to courts, better seats at lower prices, better sight lines generally, not to mention the new Henman Hill-like Jumbotron viewing garden—would appear to hide the commercialism better.

My argument for Indian Wells as a major, in lieu of New York, is straightforward. The tournament’s already a fortnight. The desert almost never sees rain. In terms of the calendar, with several weeks between the Australian Open and the beginning of Europe’s clay season, the players are fresh. (It’s why so many play doubles in the desert. As explained to me by the ATP’s Nicola Arzani, they want match time, competitive time on court, especially if they lose early in California and need to hang around waiting for Miami to start.) Walking around, chatting people up, I expected bias toward my Indian Wells Slam theory; after all, my interview subjects had paid good money to be on the grounds. Was I wrong. Seventy percent of people interviewed were against—and many were, by their own admission, hardcore tennis fans. “If something’s not broken, don’t fix it.” “I’m a traditionalist.” “I like history.” “It’s already a mini Slam.” “It’s the Fifth Slam.” “I’m surprised it’s not a Grand Slam, but…” “The US Open is still catching up anyway.” “It would become too expensive.” “It would get too crowded.” “The crowds would be unmanageable.” “We come here because it feels like a vacation.” “There are more pure tennis fans out here already.” “It would make it less special.”

Truthfully, as I drove away on my final day, I’d started to agree. My theory wasn’t just dumb, it was counterproductive. Indian Wells is special because it’s not a Grand Slam. Because it can flower in New York’s shadow. Because a billionaire, who happens to look like a Bond villain but turns out to be a Nadal fanboy, can pretty much do whatever he wants when he buys himself a giant sandbox, and we’re lucky that he loves tennis.

Then there’s also the idea that maybe Ellison doesn’t care about the US Open anyway. Maybe the Open’s not even his competition. There’ve been rumors that Ellison wants to build a third stadium as his next step, or a big hotel, or maybe the world’s finest tennis museum. He told Bloomberg BusinessWeek in 2015, “We have objects going all the way back to Elizabethan times, when tennis was played in front of the Queen.”

Since 1922, Wimbledon has had a Royal Box overlooking Centre Court. Dark green wicker chairs are reserved for visiting royalty and friends. There are 74 chairs exactly. New as of 2016, Indian Wells built a President’s box in Stadium 1, where the richierich types, plus Ellison and his guests, can watch matches. How many guests? Ellison’s box seats 75.

Geoffrey Knott is a Canadian photographer based in Los Angeles. He works primarily in sports, landscape, and documentary photography.

Rosecrans Baldwin is the author of three books. His new novel, The Last Kid Left, was published in June.

Featured in Racquet Issue No. 4