Illustrations by Dalbert B. Vilarino

one

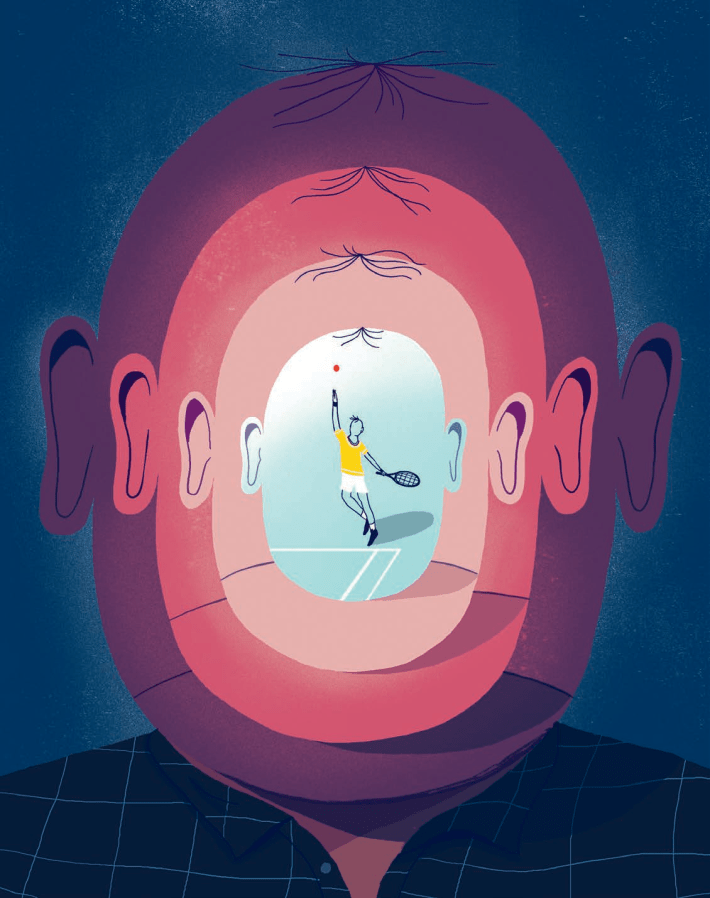

Have you listened closely to the sound a can of tennis balls makes when you pull the vacuum-sealed lid off it? Have you thought about the sound? I think it might be the best sound there is, indicating, as it does, the infinite possibilities for beauty in the world. You can, after all, behave like a couple sardine brains, you and your partner, smacking the balls all over God’s green hardcourts, wasting them. Or you can drive them with pointed grace to different parts of the court, moving each other deftly, patiently, in an attempt to gain an opening, to seize advantage, to win a point. The difference basically between what Sugar Ray Leonard and Tommy Hearns did to one another and what two hotheaded kids do when they start slugging each other. The kids are wasting the violence; Leonard and Hearns applied it to art. Boxing is a lot like tennis. Marlon McGervin taught me that.

He taught me a lot about tennis. He taught me how to listen to cans of tennis balls when I open them. He taught me how to make sardine sandwiches on white bread with white onions and mayonnaise. He showed me videotapes of Floyd Patterson and Archie Moore and Joe Louis and Ezzard Charles and Rocky Marciano and of course Muhammad Ali. When I went to visit him recently, he was watching old clips of Roy Jones Jr., a genius fighter whose lack of true competition made him seem something of a tragic figure.

‘This is Roy Jones Jr.,’ he shouted as I entered the room. McGervin had gone a little deaf. ‘Sure enough,’ I answered. We watched for a moment, then I told him what was on my mind. ‘I want to play tennis again.’ McGervin paused the screen and craned his neck to look up at me. Little about McGervin had changed in the years since I’d seen him; he’s a tall, sallow-chested man, always a little stooped and shorter-seeming than he actually is, with a shock of brushcut white hair and long, graceful hands. The paused image showed Roy Jones Jr. glowering across the ring while McGervin looked hard at me.

‘What makes you think you can play tennis now?’ he asked.

‘I think I need to try again.’

‘Why now?’

‘Well, I’m older and perhaps not so impetuous, and I think I could maybe enjoy it now.’

‘Enjoy it?’ He sounded incredulous.

I hadn’t seen McGervin in about fifteen years. He’d been my informal tennis advisor from when I was ten until I turned sixteen. Then, around the time that I started having some modest success in junior tennis, my pro, my high school coach, and my father collectively decided that McGervin’s advice wasn’t helping and they banned me from speaking to him. I gave up playing about a year later. I sent McGervin a card at the time to tell him so. And I sent him two more cards in the next couple years, one from India and, before that, one from Tufts University.

‘Have you read my books?’ he asked.

I had, though that made me part of a very small club. McGervin had self-published several books since I’d last spoken to him. I noticed stacks of author copies on his dining room table. Here are the titles:

Pocketful of Sawdust, Backhand Full of Stars: Ivan Lendl’s Failed Attempt to Win the 1982 U.S. Open and How It Changed Tennis Forever

Dream a Little Dream: How to Succeed on the ATP Tour if You’re Under Five Feet Tall: The Greatest Short Men’s Tennis Players and Why You Should Know Their Names

‘This Is My Hair! (C’est Mes Cheveaux!)’: Yannick Noah and Issues of Race & Fashion in the French Tennis Federation, 1984–1989

I said I’d read them and, in truth, I did make it through most, though not all, of all three. They were fairly incomprehensible. The Yannick Noah book alternated between English and French with neither warning nor, it seemed, purpose. McGervin was not a sociologist. He wasn’t even a writer, exactly. He had been, at one time, a pretty fair milkman. He’d delivered some milk in his day. In fact, he was wearing his crisp white milkman garb when I first met him, on public courts in Burbank, CA. Crisp white uniform, little white cap with a stiff black visor. I was alone, practicing serves, waiting for my dad to pick me up. He stood at the fence and hollered that I was frowning and grimacing at the ball on the toss and that that was no way to serve. He told me to smile at the ball and that then I could slow it down, could use good cheer, in fact, to freeze it at its apex and give it a good wallop. I tried it a couple times and the results were good. A few years later he had me laughing out loud like a deranged hyena on the toss, such that my opponents would complain vociferously to me—or any official they could find—and any spectators would shift nervously and avert their gaze, like people on the same subway car with a ranting lunatic. It was shortly after that that my dad and coaches cut McGervin out of the picture.

‘Dream a Little Dream, that one sold pretty good,’ he said. ‘People thought it was a howto book. How-to books sold pretty good for a while there. I was just ready to make some sardine sandwiches. You want one?’

‘I don’t know,’ I said. ‘Maybe so.’

His little white milkman hat hung on a hook by the door, and stacked around the living room were dozens of wire milk carriers, mostly filled with empty bottles, which took up most of the floor space. ‘Do you still deliver milk?’ I asked. He said he was mostly retired, ‘but I keep the bottles around just in case.’ The apartment had a vaguely simian odor.

When I was a little kid, I played with my dad’s Bjorn Borg model Donnay wood racquet. The Allwood Borg Superlight. On the head of the racquet it said ‘made in belgium by the world’s largest manufacturer of tennis rackets.’ Many of the things McGervin told me when I was a junior made me into, well, perhaps a singular player for my age. Like the thing about listening to the can opening. ‘Enter the whoosh,’ he would say, and so I did. The sound sucked me into a world where there was nothing but tennis, with its curious angles and oblique patterns and humming rhythms, nothing but pinging balls and spinning serves. In those years my concentration was unmatched, and I beat most players my age (and some older) just by examining the ball in air and hitting it back in the court. I made few errors, even though I was an aggressive hitter, and my opponents invariably got discouraged and started making mistakes and that was that. I never got discouraged; I lived only in the present point. As I got older that changed a little bit. I was entering puberty and my concentration wavered. When I was fourteen, McGervin told me I could improve my concentration and deal with the impending adolescent resentment I’d soon have towards my father by taking the old Donnay Allwood Borg Superlight and repeatedly whacking the hood of my dad’s BMW with it. I didn’t understand this too well but I did it anyway. I think even McGervin would now agree that it caused more trouble than it was worth, the hood-whacking.

Dad was a stalwart sort and while I spent several years anticipating the resentment McGervin told me I’d feel towards him, it never came. I remained friends with my dad (who didn’t play tennis, by the way) and we’re still close today. When I told my dad I wanted to attend Tufts University for no other reason than I liked the sound of the word, he said okay.

His business was good— he was basically a middleman for certain medical care devices, like wheelchairs and walkers and those rolling stands for funny drip bags of blood and fluids and so on, which his business bought wholesale and then resold to in-home caregivers, clinics, etc.—and he was, as best I could tell, content. We didn’t live in Burbank, we lived in Glendale, which is right next to Burbank if you’re not familiar with the geography of that part of Los Angeles. Dad still lives there. He’s retired now and he spends most of his time hitting golf balls at a sunbaked driving range where the grass is mostly brown. Marlon McGervin lives nearby and my dad told me he saw McGervin once at the Italian deli. They didn’t talk, though. They never got along.

‘John McEnroe had his Bjorn Borg,’ McGervin shouted from the kitchen, ‘but who did Roy Jones Jr. have?’

‘Whom indeed.’

‘What’s that?’

‘I agreed with you,’ I shouted.

McGervin returned with two sardine sandwiches on white bread with white onions and mayonnaise. There were also some green olives from a jar and a bag of potato chips.

McGervin took a big bite. ‘There’s a market in Culver City where you can get white sardines from Spain. White sardines! Can you imagine how perfect? Problem is they’re so goddamned expensive. They’re prohibitively expensive. But can you imagine how perfect?’

‘I need your help. I need to practice.’ McGervin eyeballed me. ‘What do you

hope to accomplish?’

‘I don’t know. I hadn’t even thought about that. I don’t know what I want. I guess what I want…’ I stopped and thought. ‘I just want to be able to shut out the rest of the world and see only the tennis ball again. I want to feel like I used to on the court.’

McGervin took another big bite of sardine sandwich and yodeled a bit. He looked happy.

two

I was McGervin’s first pupil. To be exact about it, I was McGervin’s first and only pupil. McGervin never married and had no children of his own. There was a nephew he tried to coach once, but the boy, who only took tennis lessons for a year at age nine before quitting, was more interested in baking as a hobby. When I was young McGervin told me about this boy without any hint of remorse. The kid was really a very good baker, and McGervin used to bring me some of his nephew’s cookies sometimes for after practice. Not long after the nephew quit tennis, McGervin found me. When I began, under McGervin’s tutelage, to make a mark on junior tournaments around Southern California, some other parents sought out McGervin to work with their kids too. But his ideas were invariably too radical for the parents to handle. As far as I know he never coached another kid after me.

But he really did know a lot about tennis, or at least about the art of concentration. In college I studied theology and metaphysics; afterward I traveled in India, I practiced yoga, meditated occasionally; I fasted, sometimes for weeks; I went on vision quests with Native American shamans and ate wild mushrooms and read Castaneda and drank my own urine; I wrote long stream-of-consciousness dream journals. Basically I did everything in my power to expand on what I’d learned from McGervin, to achieve a kind of internal quiet. I thought that removing the element of competition would surely allow me to achieve higher levels of consciousness. But while my success in various meditations was varied—I did sometimes see short glimpses of the silent bliss for which I strived—I was never able to accomplish what I accomplished as a preteen tennis player.

The thing is, I had a pro named Russ to teach me tennis, and I was a pretty good athlete to begin with. Russ was likable, tanned and cheery; a really good guy. So I didn’t need McGervin per se for tennis. In fact, his instruction rarely made any sense to me. ‘Eat Tourna Grip!’ he’d shout. ‘Eat clay but only green clay! I like it with milk!’ But somehow his teaching—and having tried various gurus in the years since, I’m convinced it was his teaching—turned me from an average tennis player to an exceptional one.

McGervin called me a couple days after my visit to his apartment and pronounced, ‘I think we can get you ready for a couple Futures events in Turkey!’ I had thought that the reason he wanted to work with me again was because I wasn’t interested in competing, but I guess I was wrong. McGervin doesn’t know certain things about tennis, like how you don’t make it as a 30-year-old rookie pro. But there are certain things he does know about tennis.

We agreed to meet at the courts the next day for lesson one.

three

Let’s talk strategy.’ I hadn’t even unpacked my gear. ‘Some holes are easier to dig yourself out of than others. Holes on hard courts are difficult, very jagged. Holes in clay are easier; soft matter. Don’t dig holes in grass—it destroys the very fabric of the court.’

I asked with whom I would hit. McGervin dragged out an electric ball machine and a long extension cord. He plugged in the machine and rolled it up to about the service line. He told me to put down my racquet—I did—and to come around and stand about five feet in front of the ball machine. He set the ball machine for high power and aimed it at me.

For the next ninety minutes McGervin fired tennis balls off my body. They came far too fast for me to block and soon my skin was covered with welts. One ball caught me flush on the ear and made it buzz. I thought McGervin was finished after five minutes when he frowned and shut off the machine. But he just yelled at me to take off all my clothes. I did and he started up the machine again for about eighty-five minutes more. The pain was ferocious. When the hour-anda-half lesson was up he shut off the machine and told me to get dressed.

‘I think my retina may be detached,’ I said.

‘Don’t worry about that now,’ said McGervin. ‘That’s for later. For now just remember what I said about grass: don’t get yourself dug in any holes.’

four (lesson two)

It was many months before I was healthy enough for another lesson. I’d had to check myself into a hospital for treatment of my skin lesions. The doctors said they’d never seen anything like this—it looked like I’d been scalded or burned and some lesions were infected and turning gangrenous—and the hospital staff wondered how it had happened. I don’t much like American hospitals or Western medicine and I didn’t feel like explaining to the doctors about McGervin (it would feel too much like trying to explain to my dad back when I was young: very exasperating), so I guess it was fortunate that, as they were examining and interrogating me, I passed out and so avoided answering them. In all I spent four nights in the hospital, where I was treated with various salves and lasers.

In the autumn when McGervin and I met for our next lesson I still felt very stiff and hadn’t played tennis for a long time. McGervin was setting up twelve giant stereo speakers along the side of the court as I arrived. They were really very large, perhaps five feet tall each, and only a man who drives a milk truck or similar would have been able to transport twelve of them to the tennis courts. McGervin had them wired up to several big black amplifiers on the bench; it all looked very expensive. There were snakes of cables all over the side of the court; the bench was a mess of components. Because of all the electronics I had to sit on the ground to change my shoes.

It was also probably because of the stereo equipment that I failed, at first, to notice the chimpanzee. The chimpanzee stood in the center of the court holding a racquet, looking vaguely puzzled by the whole thing. Actually I know I was puzzled and so that’s probably just transference. Thinking back on it, at that point, the chimpanzee just looked bored.

‘Why is there a chimpanzee on the court?’

‘That’s Bucky. You’re going to hit with Bucky today.’

‘He plays tennis?’

McGervin was concentrating on getting his stereo wired up and didn’t seem interested in my question. ‘You’re going to hit with Bucky today,’ he repeated. Then he added, ‘Bucky’s my student for some time now.’

He fiddled around with the amplifiers for another moment. ‘Now, look here at this stereo. This stereo is going to play music very loudly while you and Bucky are hitting. Think about Noriega, or about fugitives from the FBI. You know how when the FBI wants to smoke the bastards out they play really loud records? At Waco or wherever? That’s what this is gonna be like. I’m gonna try to smoke you out, but you don’t pay any attention, alright? You just learn not to mind. Plus it’ll be like the Super Bowl, so that after this no crowd noise will ever disturb you.’

‘I won’t ever really need to worry about crowd noise as a tennis player, will I?’

‘The internal voices can rage loudly. Crowd noise. Now, once I start the music you won’t be able to hear a word I say, so go start hitting with Bucky.’

I walked to the baseline opposite the chimp and bounced a ball a couple times. The chimp just looked at me. I hit the ball gently over the net. And indeed, the chimp must have been somehow trained because he ran towards the ball and tried to smack it with his racquet. He didn’t hit it back, though; he swung and missed and the ball just rolled by. The chimp looked around; McGervin yelled.

‘Bucky!! Get back and ready, Bucky!! I’ve been working out some of my theories on this chimpanzee while you’ve been away.’

The chimp dragged his racquet back to the service line. I hit him another gentle shot. Again he chased after the ball, swung, missed, and but then this time he kept running after the ball, waving at it with his racquet until the ball rolled to a stop at the base of the fence, where Bucky screeched and hit at it with his racquet.

‘Bucky, goddamnit, get back and get ready!!’ The chimp ambled back. ‘Hit him a serve. He’s got a hell of a return.’

‘But he’s standing at the service line.’ The chimp stood just about in the spot where my serve would land.

‘That’s okay, just go ahead and serve it to him. He’s got a hell of a return.’

I lined up and served, without much pace. The ball skipped past Bucky, who seemed to have his head turned. As best I could tell, Bucky hadn’t even seen the serve.

‘Goddamnit, Bucky!! Go ahead, serve again.’

I served again, this time a little harder. The ball landed just left of the chimp and skidded away. He watched it go by. I lined up another serve. This time I rifled it pretty good and it hit Bucky on the leg.

Bucky let out a bloodcurdling, human-sounding screech, dropped his racquet, and ran to the fence at the back of the court. Then he climbed the fence and hung on with one hand and one foot, sort of swinging like a door on hinges, screeching with all his might.

I immediately apologized to Bucky but he kept screeching. McGervin picked up Bucky’s racquet and walked to the fence. Bucky seemed to calm down as McGervin took him off the fence and carried him like a small child. He placed the chimp on the court and handed him the racquet. Then, without saying anything more, he crossed to his stereo gear.

I’d like to describe how loud the music was that came out of those speakers, but I’m hard-pressed to figure out the right words. The first piece of music was the ‘Ride of the Valkyries’ from Wagner’s Ring Cycle. I instinctively reached for my ears, plugging them with my fingers. I noticed that Bucky was doing the same. McGervin stood on the sideline gesticulating madly that we should begin hitting. Reluctantly I removed my fingers from my ears and hit a ball at Bucky. But Bucky still had his fingers in his ears, his racquet lay on the ground beside him, and the ball just skipped past him. I hit another one at him. I tried some serves. Bucky just stood there. My ears were still buzzing— amazingly; it had been months—from the pounding the ball machine had given me, and soon the music was just noise. Some car windows on a nearby street exploded. I kept serving.

Next McGervin played ‘Everytime You Go Away,’ a pop song from the ’80s written by Daryl Hall of Hall & Oates, but performed, in this more famous recording, by Paul Young. I could barely make it out through the buzz in my head. Bucky finally took his fingers out of his ears and rushed one of the twelve speakers. He clawed at the black mesh cover and tried to knock the speaker over, but it wouldn’t budge. McGervin stood on the sideline holding up a whiteboard sign for me to read. ‘jack wagner was a scratch golfer.’ Then he held up another sign. ‘eat vibrasorbs!’ He mimed that I should take the rubber vibration dampener out of my racquet and eat it. I popped it out from its place at the bottom of the strings and swallowed it whole. It was about then that the police arrived. I’m sure more than a few homeowners in the surrounding neighborhoods had already complained.

The police used billy clubs to smash up McGervin’s expensive amplifiers and speakers. When the music finally stopped they arrested all of us, including Bucky, and took us to the station.

five (lesson 3)

My third (and what turned out to be final) lesson with McGervin took place nearly a year later. McGervin had been charged by the City of Burbank with disturbing the peace, unlawful possession of a primate, and other violations of the Burbank animal codes. I didn’t get the particulars, but the upshot is that McGervin spent months in the courts and ultimately served sixty days in jail because he was unwilling to pay any fine.

When I got to the courts I found a note from McGervin that I should meet him at a donut shop around the corner. He was seated in a molded plastic booth in the window, arguing with the owner of the shop. McGervin wanted to eat his sardine sandwich and had it out on the table; the owner, apparently, wanted him to buy something if he was going to use the donut shop’s table. The owner kept saying, ‘Those sardines stink, sir!’ I bought two donuts and two cups of coffee and that seemed to calm the man.

McGervin took a big bite of his sandwich. ‘They won’t give me back Bucky. They shouldn’t call them courts, those places where you go to see the judge. They’re nothing like tennis courts. Nothing.’ He looked sadder than I’d ever seen him. He looked inconsolably sad.

Then, turning on a dime, he perked up. ‘Well, let’s get to it. Get out your racquet.’

‘What, here?’

‘Get it out!’ he ordered, and so I pulled a racquet out of my bag. ‘I remember,’ he said, ‘when you used your dad’s Donnay Borg Allwood Superlight.’ I nodded. McGervin tossed me a ball. ‘Okay, serve.’ The donut shop owner was watching us nervously; I could tell he didn’t like McGervin one bit. He looked like a regular Burbank man in his mid-fifties. He looked a lot like my dad, actually. No wonder he didn’t like McGervin.

Or it may also have been that I was bouncing a tennis ball on a racquet in his store. He by the City of Burbank with disturbing the peace, unlawful possession of a primate, and other violations of the Burbank animal codes. I didn’t get the particulars, but the upshot is that McGervin spent months in the courts and ultimately served sixty days in jail because he was unwilling to pay any fine.

When I got to the courts I found a note from McGervin that I should meet him at a donut shop around the corner. He was seated in a molded plastic booth in the window, arguing with the owner of the shop. McGervin wanted to eat his sardine sandwich and had it out on the table; the owner, apparently, wanted him to buy something if he was going to use the donut shop’s table. The owner kept saying, ‘Those sardines stink, sir!’ I bought two donuts and two cups of coffee and that seemed to calm the man.

McGervin took a big bite of his sandwich. ‘They won’t give me back Bucky. They shouldn’t call them courts, those places where you go to see the judge. They’re nothing like tennis courts. Nothing.’ He looked sadder than I’d ever seen him. He looked inconsolably sad.

Then, turning on a dime, he perked up. ‘Well, let’s get to it. Get out your racquet.’

‘What, here?’

‘Get it out!’ he ordered, and so I pulled a racquet out of my bag. ‘I remember,’ he said, ‘when you used your dad’s Donnay Borg Allwood Superlight.’ I nodded. McGervin tossed me a ball. ‘Okay, serve.’ The donut shop owner was watching us nervously; I could tell he didn’t like McGervin one bit. He looked like a regular Burbank man in his mid-fifties. He looked a lot like my dad, actually. No wonder he didn’t like McGervin.

Or it may also have been that I was bouncing a tennis ball on a racquet in his store. He looked like he didn’t really want to come back around the counter. He called out, as if across a big room, ‘No tennis in here, sir.’ I tried to smile at him, to show him it would all be okay in the end. I could tell he was still nervous. I wanted to tell him that when everything was over, it would all be okay. That ultimately it doesn’t matter if you do or don’t let a guy eat a sardine sandwich in your donut shop; it doesn’t matter if you climb Mt. Fuji or if you stop speaking to your only sister or maybe your mom or if, conversely, you love your mom or sister so much that she becomes the most important person in your life; it doesn’t matter how happy you are, how miserable, how many times your heart is broken, how many times you put it back together; it doesn’t matter if you sit and meditate and struggle for inner peace and attempt to puzzle out how you should be living, or if you simply live; it doesn’t matter really if you live badly or well, because eventually, eventually—and it might take more time than you ever thought possible, more time than a donut shop man could even conceive of—but eventually all that will disappear. It will disappear and there you will be, still, and all those adjectives (miserable, happy, moral) will cease to have any meaning; in the end, everything will be okay. Eventually, John McEnroe will have his Bjorn Borg.

I tried to smile at the donut man in a way that would indicate this but, of course, how could I put him at ease? McGervin took another bite of his sandwich and, his mouth full, looked at me expectantly. ‘Serve!’ he said, mouth still processing sardines.

I didn’t bother trying to smile at the donut man again. I bounced the ball twice and I served.

And I continued to serve amidst the smashing of glass and the spilling of gallons of coffee and the crazy twist of dozens of donuts tumbling out of shattered display cases and toppled restaurant carts. I continued to serve even as I could barely get my footing in a flood caused (I suppose) by a broken Pepsi machine. And I served awfully, awfully well.

Ben Callet writes fiction and for the screen under various names.

Featured in Racquet Issue No. 4