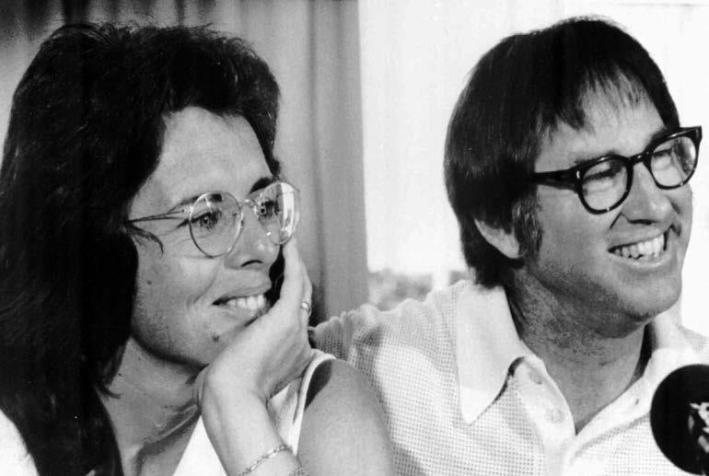

Billie Jean King’s entrance onto a Houston tennis court on Sept. 20, 1973, was more suited to a Las Vegas stage than a sports stadium. The 29-year-old player, ranked number one in the world, arrived atop a gold throne framed by flamingo-pink feathers and carried by four shirtless men. Her opponent, the 55-year-old former No. 1 player Bobby Riggs, arrived on a rickshaw pulled by models dubbed “Bobby’s Bosom Buddies.” This wasn’t a regular tennis match. It was the Battle of the Sexes.

The Astrodome was packed with more than 30,000 people—a record for any tennis match—and the atmosphere was more Super Bowl than Wimbledon. Fans drank champagne, cheerleaders danced, and a band played each player’s theme song: “I Am Woman” for King and “Conquest” for Riggs. Some men wore T-shirts featuring cartoon pigs supporting Riggs that read “I am a male chauvinist,” while women in the audience held signs that read “I love BJK.”

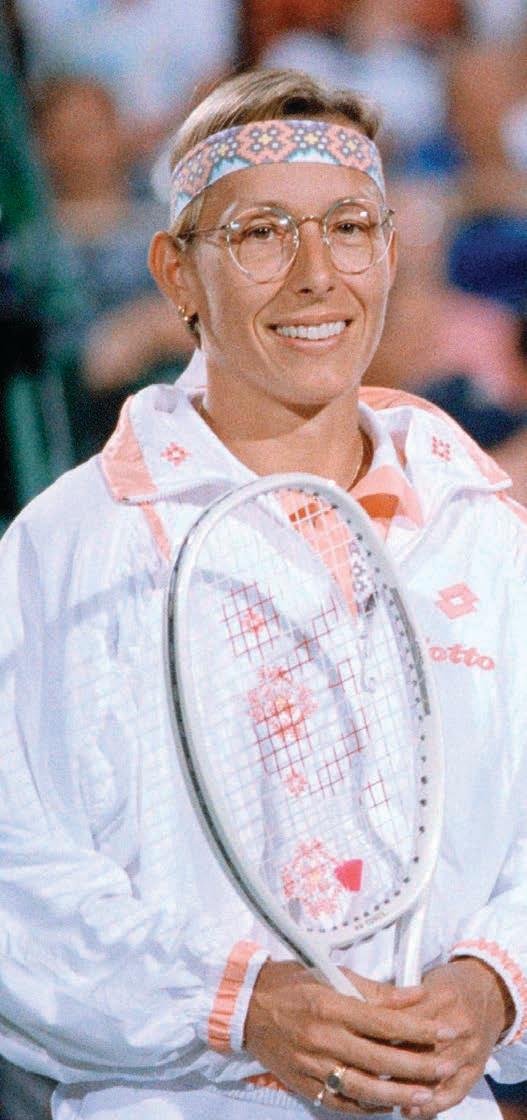

King wore a wool cardigan over her tennis dress, wire-framed round glasses, and a giddy smile. “A very attractive young lady,” one broadcaster said, his voice reaching out to the 90 million Americans watching the match on TV. “If she ever let her hair grow down to her shoulders and took her glasses off, you’d have somebody vying for a Hollywood screen kiss.”

Though King wasn’t normally a flashy dresser, she wore blue suede running shoes and a dress with a sequined patch for the occasion. Riggs wore a bright yellow sports jacket with the words “Sugar Daddy” emblazoned across the back.

King didn’t mind the gimmicks. She knew that beneath the circuslike spectacle, the match had the potential to change the lives of women everywhere.

Later this year a Hollywood version of the Battle of the Sexes starring Emma Stone and Steve Carell will be released, but it’s hard to imagine a similar match happening today.

Though there have been other male vs. female tennis matches, none have been based on the sexist premise that a woman’s athletic worth depends on whether or not she can beat a man. In 1973, feminism wasn’t mainstream and women couldn’t even apply for their own credit cards. Hillary Clinton won the popular vote by a margin of more than 2 million in the 2016 presidential election. Last year the women’s U.S. Open final sold out before the men’s. Nobody would suggest that Serena Williams isn’t a world-class athlete if she failed to win in straight sets against Pete Sampras.

When King battled Riggs, she was fighting a widespread cultural attitude that women were inferior to men. She knew a theatrical face-off was the perfect means through which to grab the nation’s attention and change their minds. But since today’s players don’t need to shift public opinion, their battles have become more bureaucratic. While that’s a sign of progress, critics say activism within the sport has become more cautious and fragmented.

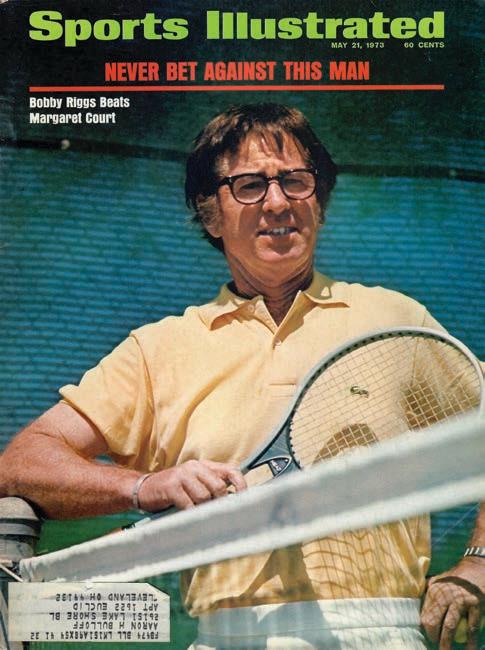

When Riggs first challenged King to a Battle of the Sexes, she declined. But when then No. 1 women’s player, Australian Margaret Court, accepted his challenge and lost, King knew the equal rights movement badly needed a victory. Leading up to the event, Riggs spouted sexist rhetoric like a broken faucet. He said women belonged “in the bedroom and the kitchen,” that they didn’t have the “emotional stability” to be athletes, and that he planned to “set the women’s lib movement back about another 20 years” by beating King.

As King bounced the ball before her first serve in Houston, she knew a win would prove women—from athletes to housewives—weren’t the weaker sex.

She won 6–4, 6–3, 6–3.

“Had I lost, women’s tennis would have suffered, Title IX could have been hurt and the women’s movement would have been damaged,” King said. “I knew it was very important I win the match if I wanted people to take women’s tennis—and women—seriously.”

That year, King formed the Women’s Tennis Association (WTA), and the U.S. Open became the first tournament to offer equal prize money. Thanks to generations of female players, notably—the Williams sisters—who continued the fight, all Grand Slam tournaments have offered equal prize money since 2007. That makes tennis an exception among major sports, but it’s still no feminist paradise.

In most tournaments, women earn 20 percent less than men. Equal pay is openly opposed by many male players and industry heavyweights, most recently by former Indian Wells CEO Raymond Moore, who said female tennis players “ride on the coattails of the men,” and Novak Djokovic, who said men deserve higher prize money because their matches are more popular.

During Grand Slams fewer women’s matches are held on main-stage courts. Women receive less media coverage than the men, and the coverage they do get is all too often sexist. After winning matches, Eugenie Bouchard has been asked about her taste in men and to twirl around to showcase her outfit. Journalists and commenters have described Serena Williams as a “gorilla,” “savage,” and “built like a ‘monster truck.’” And problems aren’t limited to players. Only three of the top 50 women’s players have female coaches, and there’s only a few women in powerful organizational positions.

In short, there’s still a lot to fight for. But experts worry that the spirit of activism among players has changed for the worse.

Now that society doesn’t believe all women should stay at home and baste turkeys, tennis activism has shifted from changing public opinion to challenging policy. The best example of a 21st-century activist is Venus Williams, who helped the WTA win a decades-long fight to secure equal pay at Wimbledon in 2007.

Williams didn’t stage a protest with other players or organize an attention-grabbing press conference. Instead, she showed up to a board meeting full of Grand Slam execs, asked them to close their eyes, and said: “Imagine you’re a little girl. You’re growing up. You practice as hard as you can, with girls, with boys. You have a dream. You fight, you work, you sacrifice to get to this stage. You work as hard as anyone you know. And then you get to this stage, and you’re told you’re not the same as a boy.” The next year, she published an op-ed in the London Times arguing for equal pay, which helped persuade Prime Minister Tony Blair to endorse the cause.

Williams targeted the powers-that-be rather than society at large. Selena Roberts, author of a book about the Battle of the Sexes, says her choice not to use flashy stunts to effect change is a sign of societal progress. “In 1973…the entire world was so behind [in terms of equal rights] you had to do something on a grand scale to elicit attention,” she says. “Venus pointed out to Wimbledon, ‘You’re so far behind the rest of the word it’s ridiculous.’”

Nicole LaVoi, who teaches sport and exercise psychology at the University of Minnesota, thinks the evolution toward activism that focuses on substantive policies is positive for the equal rights movement. “The Battle of the Sexes match was a lot about creating public awareness on a big scale…but most people know that real social change comes in the boardrooms and at the organizational level,” she says. “It’s not just taking [views] to the court of public opinion.”

While today’s players focus on important bureaucratic battles, they have lost some of the solidarity characteristic of a previous generation. In 1970 King and eight other female players dubbed “The Original 9” created women-only tournaments to protest male-run tournaments that paid them six times less prize money. Today’s players tend to speak up individually rather than as a group, with the internet providing the perfect vehicle to amplify single voices.

Andy Murray recently defended equal pay in a Twitter spat with Ukrainian player Sergiy Stakhovsky. Nicole Gibbs, a 23-year-old player, regularly writes and tweets about women’s rights and sexism—“I have had countless individuals, men and women alike, suggest to me that tennis skirts are the principal driver of revenue on the women’s tour”—which has garnered pra sise from King.

Others players speak up in the media. “I would never want my daughter to be paid less than my son for the same work. Nor would you,” wrote Serena Williams in a recent open letter about equal pay for Porter Magazine. When a reporter asked Serena Williams about being one of the greatest female athletes of all time, she shot back, “I prefer ‘one of the greatest athletes of all time.’” After former Indian Wells CEO Moore said men have “carried this sport,” Serena Williams told a press conference that her U.S. Open tickets had sold out before the men’s finals and called the former tennis player’s remarks offensive “not only to a female athlete but every woman on this planet.”

The upside of magnifying individual voices is that players have drawn attention to issues that matter to them outside of the sport. Kristi Tredway, a gender-studies professor and former professional tennis player, says of Serena Williams: “Instead of distancing herself from issues that affect her and people like her personally, as most black players did in the past, Serena really owns who she is and what she has the power to accomplish, both in tennis and for racial equality in America.” But there are down-sides to independent activism. Tredway says athletes could achieve their goals more easily if they advocated as a unit. “The WTA and ATP aren’t going to suspend their top players if there are lots of them involved in a singular social activism focus,” she says. “They are far more likely to do so if it is just one or two players.” The United States Lawn Tennis Association (now the USTA) threatened to ban the Original 9 from Grand Slam events but never took action. Recently, the U.S. women’s soccer team filed an equal-pay complaint with the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) and wore T-shirts that read “#EqualPayEqualPlay” to games.

LaVoi says that, unfortunately, today’s players aren’t interested in joining a movement. “It’s kind of like everybody for themselves,” she says. “There are few athletes outside of the Williams sisters and the national women’s soccer team that will fight for the collective good.”

Gibbs has noticed fellow players’ reluctance to express solidarity with her activism. In a recent panel with King and Chris Evert, she discussed defending equal pay on Twitter: “I had multiple girls in the locker room come up to me and say, ‘Hey, I saw your tweets last night, your messages, but my coach told me not to get involved,’ or ‘I didn’t think it was smart for me to get involved.’ I think there is far too much worrying about what other people are going to think when you’re campaigning for equality as a woman.”

Many players shy away from activism because of money. Corporate sponsors are more wary than ever of athletes who speak their minds about social and political issues. According to Tredway, athletes from King’s era had more political freedom, before the 1980s when product promotion by sports stars really took off. “Endorsements really can control a player,” she says. “They are bound by their allegiance to the corporations that endorse them, so they don’t engage in social activism.”

But others blame the lack of collective action regarding equal rights on plain old apathy. “Today’s players are not as interested in anything beyond tennis,” King said. “Those that do get involved in social issues tend to do so after their careers and that is a shame.”

LaVoi says some athletes have the delusional sense that equality has already been achieved. “A lot of young women today…are completely clueless about Title IX and the battles our foremothers fought,” she says. “They have no idea…why they should fight for gender equality.”

But exactly how players can effectively advocate in a modern context is difficult to figure out.

The fight for equal rights in tennis needs a more unified front and more passionate voices. But while the ’70s were a golden era for women’s rights crusaders within the sport, experts caution that today’s players should not borrow too heavily from that generation, either. While the Battle of the Sexes was a massive win for women, a similar showdown could have a regressive effect on gender roles if it happened today. “I think [it] would actually be just like a caricature of the women’s movement and in some ways could be more sexist than empowering,” says Cheryl Cooky, an associate professor of American studies whose research focuses on gender and sports. “What would it mean that 40-plus years later we’re still doing the same kind of performative display of women’s advocacy?”

The last person to call for another Battle of the Sexes was Donald Trump. The president has been accused by 15 women of sexual assault, so it’s no surprise that he wanted to Make Tennis Great Again by proving that female players are yuge losers. In 2000, he offered a $1 million prize for a match between either of the Williams sisters and John McEnroe at his Trump Taj Mahal casino in Atlantic City. The week before, McEnroe talked a Riggs-like game, saying that “a lot of male college kids and members of the seniors’ tour could beat the sisters.”

At the time, 20-year-old Venus had won both Wimbledon and the U.S. Open. She had landed a $40 million contract with Reebok and was disrupting white tennis culture with her beads and braids. Nobody could question her talent and strength.

Forty years ago, King’s genius was recognizing the wider cultural importance of beating a man at a tennis match. In the 21st century, Venus knew the feminist power move was to decline a similar match altogether. Her response was a form of activism in itself.

“I don’t know if I could fit him in my schedule right now,’” Williams told reporters about squaring off against McEnroe. “I don’t think it’s fair to put a 20-year-old against a 40-something person. So, I’ll let that pass.”

Angelina Chapin is a freelance writer for the Guardian and an editor at the Huffington Post.

Featured in Racquet Issue No. 2