Saving a Temple of Handball

Photos and text by Carlin Wing

There are so many ways to write, to know, to save, to do history.

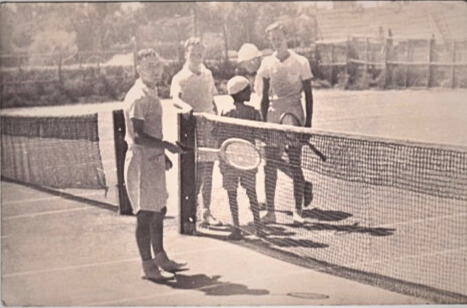

The balls in these photographs were made of liquid latex mixed with vinegar, wine corks, old sheets, old socks, medical tape, painter’s tape, rubber bands, bicycle inner tubes, and Amazon.com packing materials. They were made by a mix of adults and kids who came to the Maravilla Handball Court on a Sunday afternoon in August. Some dunked their hands in buckets of water to mold together rough rubber cores and played pickup games while they waited for them to dry. Others wrapped strips of cloth around air pillows to make bigger, bouncier objects. Alejandro Sanchez showed up with a pinhole camera that he had built and wanted to test out. At some point a band that used the court as its practice space set up in the corner and began to play.

The Maravilla Handball Court is the oldest surviving handball court in Los Angeles County. When Tommy and Michi Nishiyama passed away, the property passed to Tommy Jr., and it was not clear what would come of the place. Everyone who showed up for the ball-making workshop was connected, in one way or another, to an effort to save the court and the attached grocery from the push of development and gentrification. This effort was started by Amanda Perez. Amanda grew up in Maravilla. She has a lot of memories of the court. She remembers hearing neighborhood stories of young girls playing handball against garage walls and in public parks because girls were not generally encouraged or allowed to play on the court itself. She also remembers the Maravilla Handball Court as a center of gravity for the community. She had a vision of making it into a community center again, so she founded the Maravilla Historical Society.

I met Amanda through the website for the Maravilla Historical Society when I was putting together a ball-making workshop for an artist space in Los Angeles called Machine Project.

The workshops are part of Hitting Walls, a project that I have been working on for the past ten years. Hitting Walls developed out of my years spent playing competitive, and for a spell professional, squash. Up until that point all of the works in the project focused on that particular game—its rules, gestures, architectures, cultural and material histories. I had shot long-exposure large-format photographs of the portable glass courts set up in spectacular settings for major tournaments; made videos and performances out of play against the walls of hallways and parking lots, against stadiums and skyscrapers; and written texts that collected aspects of the sense and history. But as I moved deeper into the history of squash, other histories of ballwall play began nudging at the edges: histo ries of street games and school games, lawn games and club games, barracks games and prison games. I began wondering about the different kinds of play that occurred against different kinds of walls, with different bodies, and different balls.

The workshops were a way of posing a set of questions about balls as objects. I wanted to understand what balls were like and how bounce happened before industrialized, regularized rubber and factory injection molding. I wanted to imagine what play looked like before we had a kind of bounce that was reliable, a kind of bounce that players could fine-tune their gestures around. Squash was one of the first European games born from a rubber ball—a hollow rubber ball, to be precise, one that could be squashed. While rubber technology had been used for making balls for ritual and casual games played by numerous cultures in pre-Columbian Mesoamerica for several thousand years, Europeans arrived at a process for “curing” rubber of its less desirable properties in the early decades of the 19th century.

With the ball-making workshops, the Hitting Walls project began to move away from a strict focus on squash and toward a broader exploration of cultural techniques and material histories of bounce and ball games. The workshops were a way of knowing through handling—a way of thinking about the many different ways that regular and irregular objects have been and can be made, and of evoking the transnational and global relationships latent in our everyday objects today. In turn, the workshops produced a research question about the material and ideological underpinnings of our notions of good, true, idealized bounce. It was through asking how a specific kind of industrialized play became possible and what the political stakes of that kind of play were that directed my attention toward similar kinds of objects and interactions more generally in industrialized and informatic contexts.

I make the photographs at the workshop. The participants take their objects home and I am left with the images. In this case, the photographs became part of a one-night exhibition and auction that Amanda and I installed to raise money for the Maravilla Historical Society. The exhibition raised a little bit of money. But nothing like the kind of money that was needed to work toward, let alone realize the goal of, purchasing the property outright.

In her efforts to save the oldest handball wall in Los Angeles, Amanda has encountered all kinds of walls. Assisted by the L.A. Conservancy, she and the cohort of friends and community members she has organized into the Maravilla Historical Society have scaled some, broken down others, and been brought up short by a few. In 2012, the State Historical Resources Commission voted to list the Maravilla Handball Court and El Centro Grocery in the California Register of Historical Resources. The goal of having the Maravilla Historical Society purchase the property outright has remained unrealized. The work continues today. The effort is currently centered on nominating the property to be protected by a new Los Angeles County ordinance for historic locations. This ordinance provides stronger protections than the state ordinance—protections that are needed since workmen hired by the new owner tore apart the interior of the old grocery in January, bringing it down to the studs.

The writer Sara Ahmed wrote, “We are up against history: walls.”

There are so many ways to save history, and so many more ways to lose, erase, repress, and overwrite it. It takes work to make history into a place we can inhabit and into a thing we can hold.

Carlin Wing is an artist, writer, and professor of media studies at Scripps College. She has been a member of the Maravilla Historical Society since 2016. Fifty percent of the proceeds of print sales of the ball portraits will go toward paying the approximately $3,000 worth of fees related to nominating the property for historic status in Los Angeles County.

Featured in Racquet Issue No. 4