At the beginning of the 2016 ATP tennis season, for the first time ever there were five Frenchmen ranked in the top 20. Many countries would be over the moon with that kind of showing—they’d label it a golden generation. Jo-Wilfried Tsonga, Richard Gasquet, Gael Monfils, Benoit Paire, Gilles Simon: They’re flamboyant, they’re showmen, and they’re funny, capable of playing like geniuses and lunatics all in the space of a few points. On a good day they can beat anybody.

Yet you can’t find a nation less optimistic than the French. French tennis fans, in general, are at their wits’ end when it comes to this once-hyped generation of players: They’re all tax exiles in Switzerland, they never win anything big, they have no fighting spirit, they have no mental strength, they don’t care if they win or lose, they’re divas, they have no work ethic, they never listen, they’re uncoachable.

The tension between the players and the public, to say nothing of the media, is real. In Marseilles this spring, Simon refused to speak with Racquet, letting me know he had had enough of the topic. Monfils, who didn’t even have a mobile at the time, was unable to be found before the start of the same tournament—which he pulled out of with an injury—eventually saying he was unwilling to comment on the subject.

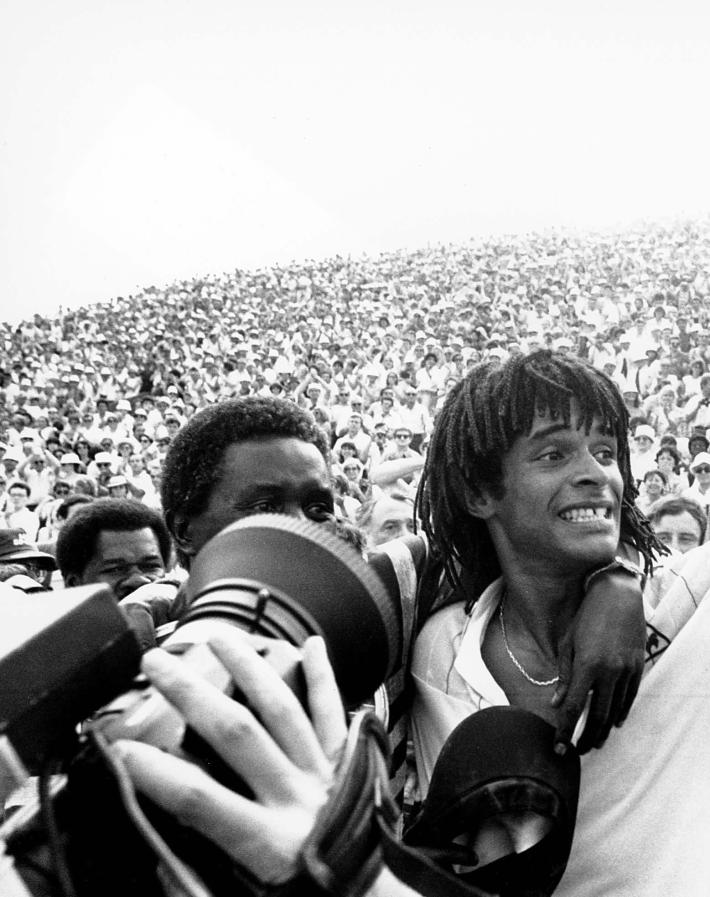

Amid this general malaise is the one Frenchman who has the résumé to inspire confidence: Yannick Noah, and he has again been brought in to coach the Davis Cup team—and restore some respectability to French tennis.

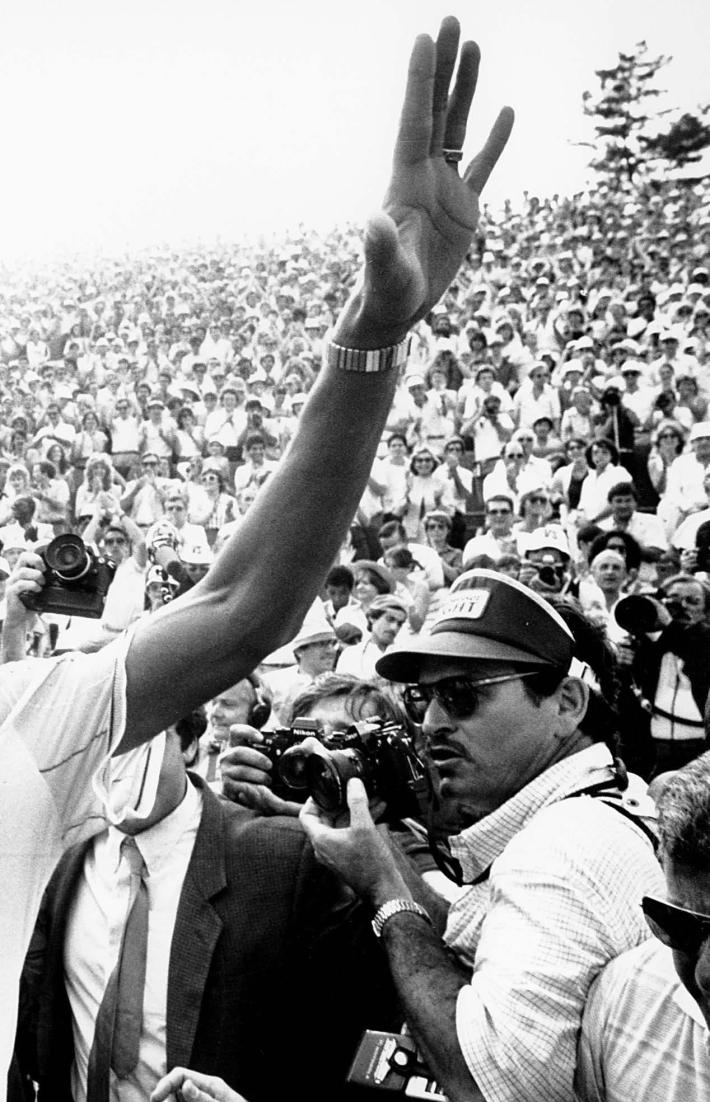

Noah has proved a masterful coach, with wins in 1991 and ’96, in addition to a Federation Cup victory in 1997. He’s the last French male player to have

won a Grand Slam, the French Open no less, in 1983. As a player, Noah was the kind of character who transcended the sport. He was known for his on-court pyrotechnics, including flamboyant tweeners and fearless dives, as well as for being one of the most stylish professional athletes ever. Born in France to a Cameroonian father, he was surrounded by models and rock stars—fathering New York Knicks center Joakim Noah with Miss Sweden 1978, Cécilia Rodhe, and later embarking on a successful career as a self-described “Afro-reggae” singer.

French tennis was a mess, and Noah knew it. “Someone called me saying, ‘It’s on fire!’ I was asked if I could help and I said yes. The team wasn’t working.” He’s been very clear about how he’s going to fix things: He’s the boss and everyone else is going to follow. “Players deciding everything never works,” he said. “That’s why there’s a captain.”

When I spoke to Monfils at the Australian Open in late January, he told me that most of the team didn’t even want to play in France’s Davis Cup tie in Guadeloupe, but that Noah was insistent. After a very public crisis, Monfils was nearly bounced from the team, all while their star, Tsonga, was in South America for the clay-court swing playing both Buenos Aires and Rio, winning a grand total of one match.

In France, the charismatic Noah’s aura is huge, and he’s convinced he can change everything: “I’ve talked with Boris Becker, Stefan Edberg, and Michael Chang,” he said last September in Roland-Garros during his first press conference as Davis Cup captain. “They all stopped playing a long time ago, but now they bring something special as coaches. We were all thinking Federer was in decline, but Edberg did him a lot of good. Same for Amélie Mauresmo with Andy Murray. There are bad coaches, there are good ones. There’s a winning culture, or a losing one. When you want to win, you need to try dreaming and make people smile. We’re often told why we’re losing, but it’s harder to explain how to win. We need to get the hope back.”

Noah’s first shot, in Guadeloupe, went exactly as planned, though it wasn’t a very tough test. The French team of Monfils, Gasquet, Simon, and Tsonga beat a Canadian team devoid of their star, the injured Milos Raonic. But the mood was great; Noah was ecstatic to be back on the captain’s bench, and the players were eager to prove they could be a cohesive team. The Four Musketeers! Back on track! More united than ever! Everybody was hoping this victorious mind-set would carry over into their individual careers.

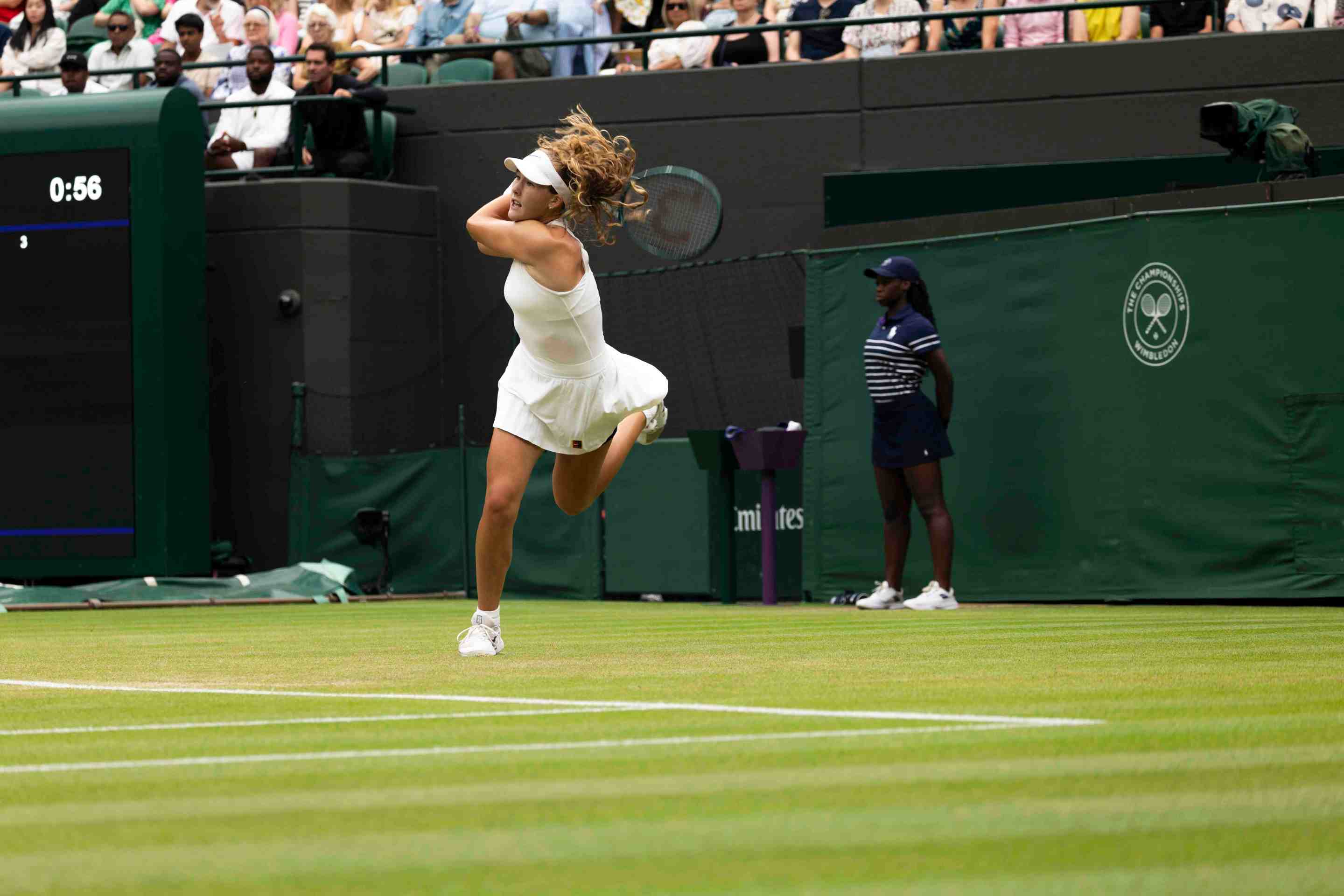

Monfils finally seemed to play up to potential this season under the guidance of Mikael Tillström, reaching the Monte-Carlo Rolex Masters final, losing against Rafael Nadal. Could he finally have a shot at Roland-Garros, every French player’s ultimate goal? Not this year. He ended up in the hospital with a virus a few days before the tournament and withdrew. Tsonga didn’t fare much better at the French Open, where he retired with an injury in the third round. His compatriot Gasquet reached the Wimbledon semifinal last year, and looked to be in good form this year before withdrawing in the fourth round with an injury. His opponent in that match, Tsonga, played bravely in the quarterfinal before losing to Andy Murray, the eventual champion. That’s the problem with underachievement: Even when you’re injured or lose to a better player, it’s hard to shake the stigma.

When Noah accepted the role of Davis Cup captain, he addressed the shortcomings head-on. “This generation: That’s zero titles,” Noah said in L’Equipe at the end of February. So while technically, on Feb. 22 of 2016, Tsonga, Gasquet, Monfils, Simon, and Paire made French history by all being in the top 20, four of them had been there for years: In 2008, the French Big Four—Tsonga, Monfils, Gasquet, and Simon—were already in the top 20, and there has not been much glory to speak of in the interim. The tennis world is defined by what you’ve won, and between all these players, they haven’t won a single Grand Slam. Or a Davis Cup.

One could also make a case for France’s pedigree in doubles, with Julien Benneteau and Edouard Roger-Vasselin winning Roland-Garros in 2014, and Nicolas Mahut and Pierre-Hugues Herbert winning the U.S. Open last season, then taking home victories at Indian Wells, Miami, and Monte Carlo, leading to Mahut earning the top doubles ranking. The pair again triumphed at Wimbledon in July.

If we say they’ve underachieved, it’s because many of us who watch tennis believe they’re capable of so much more. The French fans still remember the U.S. Open 2014 quarterfinal, when Monfils led Roger Federer two sets to none and had two match points in the fourth. I was courtside, watching what should be a regular Grand Slam occurrence, Monfils making a deep run, battling with the best players in the world. Gasquet still shakes his head at his friend’s brush with greatness: “That was the most feasible one.

The French Davis Cup team in Guadeloupe ahead of their tie against Canada in March. Some of the players grumbled about being made to travel to the West Indies for the matches. (Rankings as of July 2016.)

Having a match point to then play Cilic, and Nishikori, who was in a wheelchair”—a reference to Nishikori’s injuries at the time—“that was a real opening.”

Noah, getting into it, as Jo-Wilfried Tsonga approaches the net.

Tsonga lost the French Open 2015 semi against Stan Wawrinka, who went on to win the tournament. In 2012 Tsonga lost a quarterfinal against Novak Djokovic, despite having four match points, and he lost close Wimbledon semifinals against Murray that same year and Djokovic in 2011—great chances to win a Slam that might never come again.

Some critics point to the French tennis system, saying they coddle players who turn out technically perfect but lack a winning mentality, ambition, mental toughness, or love of sacrifice. The federation offers amazing facilities and sends its medical and fitness staff to some tournaments. Financial help is generous by global standards. The country even subsidizes coaches for some of its top players.

There’s also the fact that France has had an amazing generation of players…at probably the worst time. The real Big Four— Djokovic, Federer, Murray, and Nadal—have minimized most players’ chances of ever winning a Slam. But Gasquet won’t make excuses: “Marin Cilic and Stan Wawrinka won a Grand Slam, so it’s not an excuse. Each time, I wasn’t good enough and lost against Federer, Nadal, and Djokovic, who were at their best and ended up winning the whole thing. They were better,” he said. “Sometimes you need a bit of luck, and it never happened for me. I played Novak last year in the Wimbledon semis, but he nearly lost against Kevin Anderson in the fourth round…. Imagine you play Anderson for a spot in the final.… No, I had Djokovic at his best, as Nadal in New York in 2013, who was just unplayable. And Federer on grass in years when he wasn’t beatable there. I haven’t lost because I messed up or something, but because each time they were the best they could be and I didn’t stand a chance.”

As of next year, all of France’s top players will be in their 30s, which should inspire a sense of urgency. Noah might just be the shock to the system France’s stars need: He’s got a bigger ego, a bigger temper, and the unimpeachable credential they all lack—a French Open title.

Noah himself seems to understand the stakes: “This generation created lots of hopes because it’s unique,” he said. “But if those players happen to be too tough to handle, then that would mean they don’t deserve to win. So be it! Some people don’t know how to win. There’s something negative surrounding that team today. People don’t believe in them anymore. This situation, it’s an emergency.”

Gasquet agrees that the country isn’t entirely pleased with his generation, a fact he’s had to grapple with for most of his career. “Crowds wants to see a Grand Slam winner, and I think that’s the issue,” he said. “We’ve all been rather close, but it never happened. I’ve always received a lot of support from the crowd, maybe also because they love the one-handed backhand. And I’ve been on tour since I was very young, so they’ve always known me. But then you’ll always have some who say, ‘He never won a Grand Slam.’ That’s fine, I accept that. I don’t know how many seasons are left for me, but I know I can still play high-level tennis. Winning a Grand Slam, I don’t know. But I’m able to get back into semis, winning big tournaments and the Davis Cup, too, so why not?”

Tsonga has said over and over again that he still feels he has a Grand Slam in him, and Monfils also dreams of the French Open. “My goal is the same every year, but I’m gonna stop talking too much about that. I now want the results to speak for me,” Monfils said in Melbourne.

So you see how one country’s hopes and dreams have come to rest on one man, deemed capable of reaching excellence and soothing a nation’s long-held anxiety. There’s a pervasive feeling in French tennis: When everything else has failed, you go back to the only thing that worked—Noah.

“You can get this extra something that helps winning the Davis Cup, and that’s what we’re looking for,” Gasquet said. “Yes, I think the captain’s words can change things,” he added. “Noah, for us, is a bit of a legend, someone who is above French tennis and who won the French Open. We need that.”

Stade Amédée Détraux in Baie- Mahault, Guadeloupe

It was a new-look French team that took the court in Trinec, Czech Republic, for the Davis Cup quarterfinal tie in June. With Gasquet out with a back injury and Monfils still dealing with a viral infection, the stalwart Tsonga this time was joined by the newly minted doubles powerhouse of Mahut and Herbert, and the 22-year-old Lucas Pouille, fresh off a run to the Wimbledon quarterfinals. France ground out a gritty victory in Trinec against a strong Czech team, seeming to prove the French team was ready to suffer together in order to get the trophy. It might have been the turning point Noah was hoping for. (France will take on Croatia in the semifinals in September.)

Noah’s luck may lie in the fact that his players are now aware they won’t get many more chances. “Players now need to feel responsible. Nobody will be allowed to hide,” he said. “Things need to be said clearly, and mistakes of the past need to be taken into account,” he continued. “I just want them to win, to live this at least once. How long has it been since we’ve won anything?! Maybe I’m crazy, but I feel I can [elevate] them all. It’s unbelievable how strongly I believe in them.”

Carole Bouchard is a French journalist who has covered tennis for L’Equipe, Le Parisien, La Dernière Heure, Sports Illustrated and Radio Canada.

Featured in Racquet Issue No. 1