Illustration by Sergio Membrillas

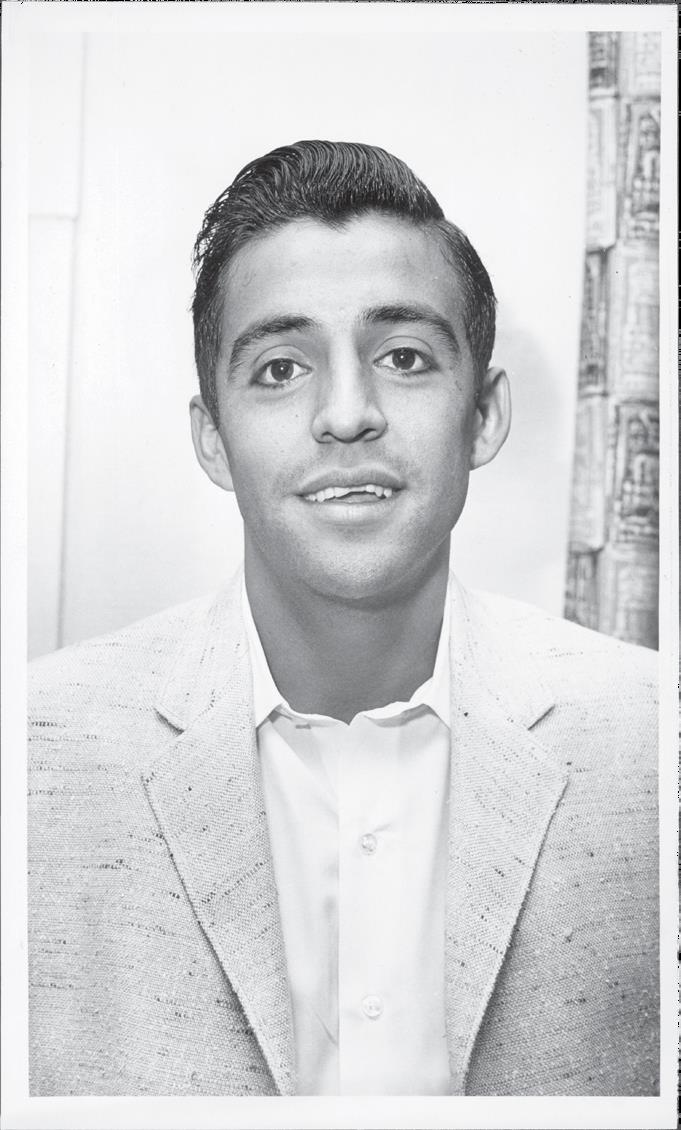

On the afternoon of June 4, 1969, as the crew of Mexican Airways Flight 704 prepared for takeof in Mexico City, the pilot asked the 79 people on board an unusual question: Would they mind if he delayed the fight for a passenger who was late getting to the gate? That request would typically have elicited groans and eye rolls, but this was no typical latecomer. When the door to the plane swung open and Rafael Osuna, Mexico’s most famous athlete, walked down the aisle, fashing his familiar toothy grin, a roar of excitement flled the cabin.

It was a familiar sound to Osuna. Just 10 days earlier, at the advanced tennis age of 30, he had achieved a lifelong goal by leading his nation’s Davis Cup team to victory over mighty Australia in front of a delirious audience in Mexico City in the early rounds of the tournament. Using every veteran move and tactical trick in his unorthodox playbook, with the crowd chanting his name throughout, Osuna had won both of his singles matches, as well as the doubles, to clinch Mexico’s frst win over the 16-time Davis Cup champions. During the previous decade, the little man with the hands of gold had carved out, in his own elegant and unassuming way, an elevated place for his country on the tennis map. Now, with his retirement around the corner, it was ftting that Osuna would close out the ’60s by carrying Mexico to the summit of his sport.

Yet his triumph, and his nation’s, would soon be engulfed by tragedy.

As Flight 704 approached its destination in Monterrey, Mexico, it flew into a storm. Circling the airport in a holding pattern, the pilot—the same man who had held the door open for Osuna a few hours earlier—turned the wrong way and few into a 6,000-foot mountain. The Boeing 727-64 burst into fames. Everyone inside was killed.

“The ’60s never ended,” veterans of that revolutionary decade used to say. For people involved in tennis, though, and especially in Mexican tennis, the decade came to a horribly defnitive halt when Flight 704 crashed into the mountains outside Monterrey. Osuna had been the country’s pioneering tennis star. He was the frst Mexican to win a Wimbledon title, in doubles with Dennis Ralston, in 1960; the frst to win the U.S. Nationals (now the U.S. Open) in singles, in 1963; the frst to lead Mexico to a Davis Cup fnal, in ’62; and the frst to be ranked No. 1.

Osuna brought Mexican tennis to the world stage at the same time that the country was trying to modernize itself. By the mid- ’60s, the Mexican economy was expanding at a 7 percent clip, and in 1968 it became the frst Latin American nation to host the Olympic Games. That year tennis also rejoined the Games for the frst time since 1924, as a demonstration and exhibition sport. Osuna won singles gold in the exhibition event, and doubles gold, with his countryman Vicente Zarazua, in the demonstration event.

Osuna would have even more success with another Mexican player, Antonio Palafox. The duo won the doubles at the U.S. Nationals in 1962 and Wimbledon the following year. But the nation’s tennis renaissance wouldn’t survive Osuna’s death. Though no Mexican man or woman has reached a Grand Slam fnal since Osuna, the silky fnesse game that the country’s players specialized in would live on in an unlikely place: the silky fnesse game of Palafox’s most famous student, John McEnroe.

Osuna’s death also marked the end of another golden age in tennis, one that went far beyond Mexico’s borders.

The ’60s were the sunset years for the game’s amateur era. It had begun in 1877 with the frst Wimbledon, which was reserved for “gentlemen” of inherited wealth. It ended 91 years later at Wimbledon in 1968, when the All England Club fnally allowed professionals to tread its lawns. Whatever its injustices, the amateur circuit was a place where artistic tennis, rather than merely practical tennis, was allowed to fourish. While the world’s best players—Rod Laver, Pancho Gonzalez, Ken Rosewall—competed for their lives on professional barnstorming tours, the merry, friendly, sometimes faky band of amateurs known as “tennis bums” traveled the world, postponing adulthood for as long as they could.

Looking back on that rarefed milieu and its late-’60s decline, tennis historian Bud Collins wrote, “Style vanished as big money appeared. Professionalization replaced fun and games, and the Civilization was doomed to be Lost.”

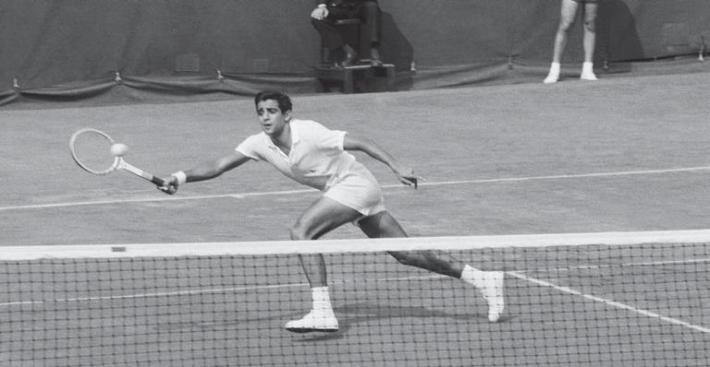

Even as the Lost Civilization forced its citizens to wear all white, it drew a colorful cast of characters to its courts. One of the most appealing was Osuna. Known as El Pelón (“The Bald”) to fans and Rafe (not Rafa) to friends, he was just 5'9", but what he lacked in size he made up for in the traits that make any player worth watching: quickness, touch, creativity, variety, thoughtfulness, and all-court skill. Osuna’s shoulder turn on his serve was a marvel of fuidity, and his McEnrovian backhand volleys seemed to emerge straight from his hip pocket.

GETTY IMAGES

There are fan favorites and “players’ players” in tennis. Osuna was both, but he was also a “writers’ player.” To the end of his life, Collins fondly remembered his early trips to Longwood Cricket Club to cover the National Doubles, an event where Osuna and Palafox were a headline attraction. Another Hall of Fame tennis writer, Steve Flink, had a similar experience after happening on an Osuna match at the All England Club in 1965.

“I was 12 years old and it was my frst time at Wimbledon,” Flink remembered. “I was wandering around and saw Osuna, and his game just got me.”

“He was a beautiful player, with a lot of variety. He moved elegantly, and he could attack the net for a little guy. He smiled a lot, too. Watching him inspired me, and I began to become fanatical about tennis.”

“Osuna drew you in,” Flink said.

One of Osuna’s doubles partners, Dick Leach, could testify to his friend’s uncanny talent and sly sense of humor. In an interview with journalist Joe Jares, Leach described a match he played with Osuna against Stan Smith and Bob Lutz.

“I couldn’t buy a return on Stan’s serve,” Leach said. “So Rafe said he would shake Stan up by returning his serve from the service line. Rafe was hitting half-volley returns of Stan’s big frst serve! Stan got so shook up he started trying to hit Rafe with his serve.”

In 1969, just before Osuna’s death, Leach found himself facing his friend in a doubles match in Los Angeles. When Osuna’s partner asked him which side he wanted to play, Osuna smiled and said, “I won Wimbledon on the forehand side with Ralston, and on the backhand side with Palafox. So I guess it doesn’t matter which side I play. How about you?”

It’s not boasting if you can back it up, and Osuna backed up his words at the game’s highest level. Flink has vivid memories of Osuna’s biggest win, over Frank Froehling in the fnal of the 1963 U.S. Nationals. Half a century later, the match stands as one of tennis’s tactical masterpieces.

“It was the giant versus the giant-killer,” Flink says. “Froehling was 6' 5", but Osuna stood way back and sent up what we would call moonball returns now. Frank didn’t know what to do with them. That match was talked about for a long time.”

While Osuna’s victory at Forest Hills was celebrated across Mexico, one of the frst calls he made after his win was to Los Angeles. It was there that his tennis career had begun, and he wanted to share his triumph with the man who had done the most to help him achieve it, legendary USC men’s tennis coach George Toley.

It’s not boasting if you can back it up, and Osuna backed up his words at the game’s highest level.

In his 27 years at Southern Cal, Toley won 10 national titles and prepared dozens of future greats, including Ralston, Smith, and Lutz, for the pro ranks. Just as signifcant was the pipeline that Toley, a lanky California native who had a lifelong love for Mexico, created for Latin American tennis talent on that mostly white, famously conservative campus. In the 1950s, Toley recruited Peru’s Alex Olmedo, who would go on to win Wimbledon in 1959. Ten years later, he guided Mexico’s Raul Ramirez onto the pro tour.

But the coach never had a student, or an athlete, quite like Osuna. For years Toley had heard his name from his Mexican players, who claimed he was the country’s most talented prospect. When Osuna fnally arrived on campus in 1960, Toley had to look hard to see it for himself.

“Everything Osuna did on the court was bad fundamentally,” Toley told Jares, “in part because he was such a natural.”

“He had great hand-eye coordination and quickness. He didn’t bother to get into position for his strokes…. We had to tear his game apart.”

Osuna, a multisport athlete, even tried a basketball-style head fake when he hit a volley.

“He thought that was a clever thing,” Toley said. “He planned to volley to the left, but he looked to the right. You just don’t do those things in tennis.”

But there was one aspect of Osuna’s game that Toley did like.

“He could move like a GOD.”

As quick as he was on the court, Osuna was even quicker on the uptake. In the mornings, Toley would give him tips on his ser ve and forehand volley; by the time he returned the same afternoon, Osuna would have made signifcant progress on those shots.

“Rafe always did everything I told him,” Toley said. “He never questioned me.” Within two months, Osuna had transformed his backhand from a weak slice into a powerful drive.

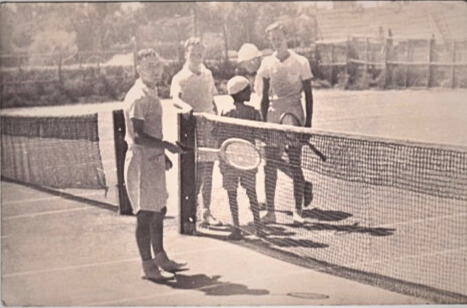

In the summer of 1960, Ralston, one of the country’s top prospects, agreed to come to USC. When he met with Toley, the coach had a suggestion: Why not enter the Wimbledon doubles with Osuna? The two young men had never played together, but Toley hoped the trip would help them “jell” before USC’s season began. Did it ever: After barely surviving their frst-round match, 16–14 in the ffth set, Osuna and Ralston went on a magical run through the draw, upsetting Rod Laver and his partner in fve sets in the semis and winning the title. Osuna and Ralston had yet to play a collegiate match, but they were already Wimbledon champions.

When Osuna did take his place in the USC lineup the following year, he put himself at the heart of one more golden age: College tennis, and in particular Los Angeles college tennis, would never be stronger than it was in the 1960s. In those years, USC was led by Olmedo, Osuna, Ralston, Smith, and Lutz, while across town Arthur Ashe, Charlie Pasarell, and Jimmy Connors took the court for UCLA. In the 12 years from 1960 to 1971, USC won seven titles, UCLA fve.

Among these powerhouse squads, though, the 1963 USC team reigns supreme. Inside Tennis magazine voted it the greatest college tennis team of all time, confrming a long-held consensus. The Trojans won the NCAA title, and defeated an outstanding UCLA team 9–0—Osuna contributed with a 6–2, 6–4 win over Ashe. Most amazing of all, Osuna played No. 2 for USC that year (behind future pro Tom Edlefsen), yet ended up the No. 1-ranked player in the world and the champion at Forest Hills.

“The Trojans of 1963 were not only great players,” Toley remembered, “but great guys and great friends. There was wonderful camaraderie on that team.”

AP PHOTO

While Osuna and Ralston played together for USC, they found themselves on opposite sides of the net during a Davis Cup tie between the U.S. and Mexico in Mexico City. When Mexico won the clinching point, fans poured onto the court in celebration. Instead of immediately joining the party, Osuna tried in vain to push his way through the crowd to console his American friend.

Like fellow stars Roy Emerson and Arthur Ashe, Osuna worked as a spokesman for the tobacco giant Philip Morris. He served as a liaison between the Mexican government and the U.S. company, which was erecting a factory near Mexico City. This was the start of tennis’ much-criticized dalliance with the cigarette business, which would eventually lead to Philip Morris’ women’s brand, Virginia Slims, becoming synonymous with the WTA in the 1970s. For Osuna, though, the job left him fnancially secure enough that he didn’t feel pressure to turn pro. To him, the game remained a game.

It also remained a team sport, in a way that it doesn’t for most players today. Osuna saw how his USC team could unite white Americans with Latin Americans. He saw how the amateur circuit could unite an international cast of characters and put them on a level playing feld. And he saw, in 1969, how his Davis Cup team could unite a country.

Ten days after leading Mexico past Australia, Osuna’s remains were found in the mountains of Monterrey. He was identifed by the Rolex watch he was wearing on that fateful plane ride. He had won it with Ralston at Wimbledon, on their innocent run to the title nine years earlier.

For those who mourned the end of amateur tennis, and of the gentlemen’s game it had been, Osuna’s death came as a fnal blow. One of the sport’s last gentlemen was gone too.

Stephen Tignor is a senior writer at Tennis magazine and Tennis.com, and the author of High Strung.

Featured in Racquet Issue No. 3