He flows like liquid around the court.

Whippet-thin, he skitters and hops and stops and starts like snowmelt fghting gravity in a mountain brook. He’s incredi- bly fast. His speed is beautiful. It is not just the hyperkinetic acceleration and economy of movement and graceful balance but also the deadly anticipation. He has decades of ball-striking experience in various racquet sports at the highest level. He knows where the ball is going.

“If people haven’t seen the game before and see him play,” said Jonathan Larken, his doubles partner, “then they always comment: ‘He looks so much faster than everyone else.’ Everyone else on courts looks fustered and he looks like he’s hitting a beach ball. He’s got so much more time than you. The only time I get close to slowing down his antici- pation when I am playing singles with him is when I do something unorthodox and unex- pected. Of course, it is very hard to do that and consistently hit a great shot. You’re just as apt to make an error.”

“He’s extraordinary in what he can do,” said another partner and regular opponent, Neil Smith. “He’s doing things that no one else has done before. A lot of people have many or most of the skills. When I was world champion, I read the ball well but wasn’t ex- tremely fast. But he doesn’t have a weakness. He’s quick, reads the game well, moves ef- ciently, gets early to the ball—gets there so early he has options.”

James Stout, the world champion of rac- quets, is one of the most extraordinary ath- letes on the planet, and yet no one knows about him. Over his career, probably less than one thousand diferent people have col- lectively seen him strike a ball in racquets, the sport he’ll be remembered for.

A left-handed polymathic genius with a racquet, Stout played professional squash for four years after high school. Based in Bel- gium, he entered the World Championships and the Commonwealth Games and won the 2005 Island Games softball doubles title. He reached world No. 116.

New court, Tonbridge School, Tonbridge, England.

Johnstone’s photographs of racquets courts are from his new artist’s book,

Sixty by Thirty, published by S_U_N_, which also published Johnstone’s

East Court on court tennis (www.thesun.solar). Johnstone is also a keen participant in these games and has won 12 United States Senior Championships in court tennis.

Presently, he’s ranked 33 on the North American pro hardball doubles tour and is a feared left-waller. He’s partnered with many of the top pros, including Ben Gould and Clive Leach. When he’s had the time and regularly entered tournaments, he’s been a top 10 player.

In the game of court tennis, Stout is tagged as a potential world champion. He captured the U.S. Open in 2010—just the second time he entered the event. He’s been ranked as high as No. 4 in the world; presently he’s No. 11. In November 2016 he played in the British Open. He lost in the second round in the singles and made it to the quarterfnals in the doubles. His partner was Rob Fahey, the greatest player in history, and some observers thought it was interest- ing that Fahey, able to partner with almost anyone, chose Stout.

He’d be a lot better at squash doubles or court tennis if he had the time, but he spends his days giving lessons, stringing rac- quets, making balls, and humoring members at the Racquet & Tennis Club in New York City, and he has one major priority at the moment: to be the greatest ever in racquets.

“Racquets” is the proper spelling.

Don’t be fooled. It was “racquets” every- where a century ago. You see this in every 19th-century book. You see this at Eton, a longtime home of the game, where all the old champions boards spell it correctly. Only in the 1920s did the British, in a ft of anti- French pique, started to spell it “rackets.”

The game is simple. The shorthand is golf in a squash court.

The longhand: A racquets court is a dark, gray, medieval shell, made of slate. The size of the court is 30 by 60 feet—about twice the size of a squash court. The bats are long (30 inches long), tiny-headed, and wooden. The ball is a composite of polymers—the cores are made at an old golf-ball factory in England—wrapped in twine and covered with white athletic tape. The sport is incred- ibly fast, with the ball rocketing at speeds of over 150 mph, so fast that the referee calls out “Play” after every stroke to tell players that it is safe to hit the next ball. The one thing everyone talks about is how dangerous racquets is. People lose eyes (almost all En- glishmen masochistically eschew protective goggles), and the bruises from a ball hitting a leg last for weeks.

Racquets is like golf in another way: Some afternoon you can play and fnd it incredibly frustrating, whifng on balls, framing others, banging volleys left and right. But then just once you’ll swing hard and connect in the infnitesimal sweet spot and the ball will can- non exactly where you want it to go. It makes you want to come back for another session.

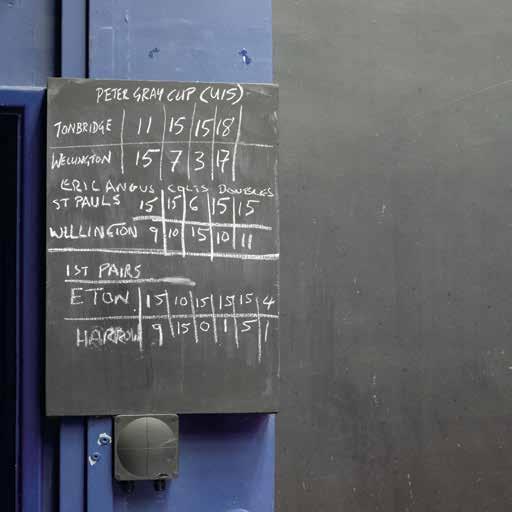

The game is almost absurdly obscure. The frst book on racquets was published in 1872; the last book on racquets was pub- lished in 1926. Nothing since. There is one court in Canada, seven in the U.S., and 28 in England. Two city clubs in England—Queens and Manchester Tennis & Racquet—have courts, but otherwise racquets in England is a schoolboy and military game, with the elite public schools producing the vast majority of activity each winter.

That makes it even more delicious, be- cause the origins of the game are at a cou- ple of debtors’ gaols in London. The game was invented in the early 18th century as an outdoor, makeshift version of court tennis, played originally at the Fleet and King’s Bench prisons. (The frst world champion, in 1820, was a prisoner at the King’s Bench, and all the champions up until 1862 came out of either the Fleet or King’s Bench.) It spread around the world, frst played in alleys and courtyards and then in constructed courts usually attached to taverns. The frst bona fde court in the U.S. was built in 1793 on Allen Street in Manhattan’s Lower East Side.

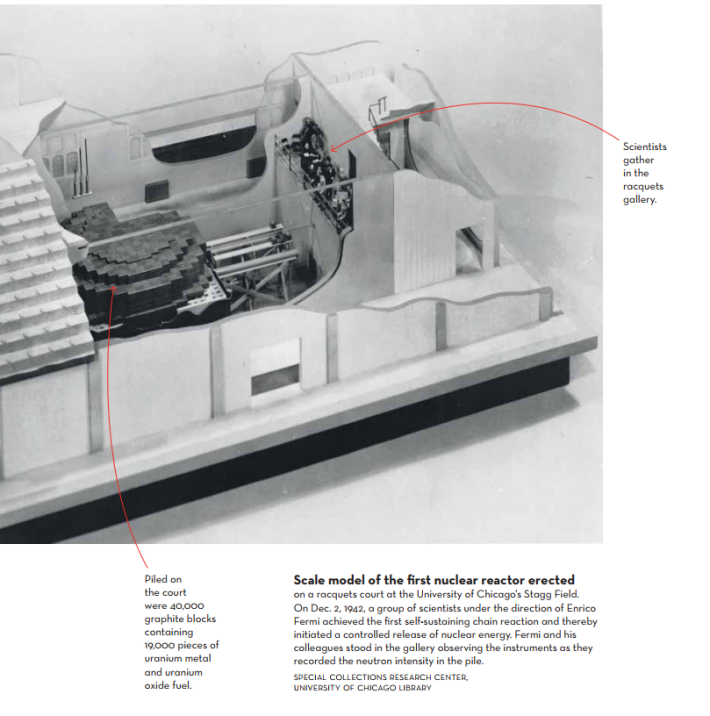

There are traces of a long history every- where. Dickens wrote about racquets. The frst nuclear reaction in 1942 was catalyzed in a racquets court at the University of Chicago. Many dozens of defunct but still recognizable racquets courts exist around the world. You can fnd old courts in Buenos Aires and Gibraltar and India and Jamaica and Ireland and Burma and St. Lucia and Melbourne. A half-dozen former U.S. courts are extant. It is a delightfully dislocating feeling to stand in a ballroom or lounge or squash doubles court and imagine hearing the distinctively percussive smack of a rac- quets ball hitting the wall.

Racquets is also the father of squash. Racquets came to Harrow School outside London in the 1820s. Younger boys, impa- tient at waiting for court time, used rubber balls (after the vulcanization of rubber in the 1840s) to create a slower, easier version of racquets, which they called baby racquets or squash racquets.

James Stout comes from Bermuda.

Not the Dark & Stormy-swizzling, scooter- riding side. He is seriously local. His moth- er’s family has been there for centuries. His grandmother was one of the frst women to drive a car on the island. His father came out from England in his 20s. The four Stout boys—Mike, James, Andrew, and Chris— went to Saltus Grammar. Stout used to jog the mile from their Smith’s Parish home to the squash club in Devonshire. Upon turning 13, each Stout boy headed back to England to attend Cheltenham College.

James Stout was about fve feet and 90 pounds when he arrived at Cheltenham. “He was a little whippersnapper,” said Mark Briers, the racquets coach at Cheltenham. “He was tiny, played with two hands on the racquet on the backhand. Couldn’t lift the bloody racquet.”

Windsor, England.

As a fve-time Bermudan junior squash champion, Stout was recruited to Chelten- ham for squash but nonetheless fell in love with racquets. Conventional thinking was that cricketers, with their straight-bat tech- nique and iron wrists, were better suited to learn racquets than squash players with their slappy strokes. But Stout took to the game. During the day, he and the other players would hang out in Briers’ tiny ofce, drink cofee, and lounge around. Then, after din- ner before study hall, they’d slip over to the courts to play.

Stout got good. “He could read the ball and he could move,” Briers said. “He quickly worked out the game. You can’t teach kids about spin in racquets. He watched. He soaked up information, as the best sports- men do. They are always the best observers.” As he got older and grew, he was able to put more weight on his strokes. He twice won the Public Schools singles and doubles titles, meaning he was the best junior player in the world. “Stout is quick about the court, which gives him a wide choice of shots to play,” read the Tennis & Rackets Association’s annual report after his second straight singles title. That sums up Stout in a nutshell.

“You were put on this earth to hit a ball,” Stout’s father told him when he graduated from Cheltenham. After four years in An- twerp giving pro squash a go, Stout called Briers and talked about getting back into racquets. Briers learned that a job was open at the Racquet & Tennis Club. Stout was in Melbourne playing squash for Bermuda in the Commonwealth Games. Connecting through New York on his way back to Ant- werp, Stout took a cab from JFK during his layover and showed up at the R&T for his interview. His luggage was lost, so he had no gear. He had just endured 24 hours of trav- eling. He borrowed sneakers and went out on the racquets court with the head pro at the R&T, Mike Gooding. Stout had played racquets only twice in the past four years. Gooding, a good but not great racquets play- er, went up 14–2 in their trial game. “I started thinking, ‘Oh, this is about the worst inter- view possible,’” Stout said. He managed to climb back and win 15–14. He got the job.

Stout’s rise to world champion was fast and secretive. His game, when he arrived at the R&T in September 2006, had signifcant faults. His serve was mediocre. As a junior, he never really learned to put proper cut on his serves, especially on the backhand (like most southpaws). He would just poke it into play like a squash player does. He also used to take the frst game of a match to warm up. He didn’t overfow with confdence, either. The frst time he played with Neil Smith, a former world champion and assistant pro at the R&T, he held game balls and lost. “I thought, ‘James, that was your only chance to take a game of a world champion and you lost,’” Stout said.

“He was a skinny little runt,” Smith said. “In those frst months, I’d beat him 15–2, 15–1.” As he improved, Stout didn’t play tour- naments. He wanted to win events so that he’d earn a reputation as a serious challenger for the world championship (until two years ago the guidelines for who earned the right to challenge the world champion were vague and subjective). “I didn’t want to lose in the quarters and be seen as a ‘decent player,’” Stout said.

“James studied the game,” Larken said. “He fgured out angles and strategies. He un- derstands theory. He will alter the angle of his strokes, deliberately trying to get the ball where it is uncomfortable for you. To exe- cute such a shot consistently is very hard. He varies his serves. He hits a three-wall boast. Unlike James Male [the world champion in the 1990s], who hit everything straight and tight, Stout plays more angles.”

In his frst events, Stout stood out. He sported a bandanna around his head, and unlike most players he didn’t ritually tap the wall with his racquet just before serving. Stout surprised everyone by winning match after match.

He went over to London for the 2008 British Open. This was the true test. He lost the frst game of the fnal to Alex Titch-ener-Barrett. It was brutal. ATB went up 8–0 before Stout got a point. Then Stout turned it around and didn’t lose another game.

He had arrived. He took the world title later in 2008 and easily defended it again in 2010 and 2015. Last November he and Larken won the world doubles title, without too much trouble. Stout is just much bet- ter than his colleagues. He has developed a routine of playing against Smith and Larken, two on one. They do this in the summer, in oppressive heat, for three hours. A few years ago when they started this routine, Smith and Larken would win easily. Now only if they are playing well do they have a chance to cop a game.

Observers now place him up against the greats: James Male, who won the world ti- tle a record six times; Geofrey Atkins, who reigned from 1954 to 1972; Charles Williams, who captured world titles 18 years apart and in between survived the sinking of the Titan- ic; or even Peter Latham, who not only won fve titles at the turn of the 20th century but also was the world champion in court tennis.

He is James Stout. Not Jamie.

His parents call him James, his childhood friends call him James, his Cheltenham teammates call him James. His fancée calls him James. He introduces himself as James. The “Jamie” started when a British report- er, Norman Rosser, dubbed him Jamie when reporting on his Public Schools wins. Now everyone does it.

Fitness is his bête noire. The main reason he failed to go further in pro squash was he couldn’t handle the physical challenge. His squash coach in Belgium, Shaun Moxham, said that Stout lacked endurance and strength and couldn’t handle the training load. “The frst time I played with Moxham,” Stout said, “I was absolutely dead after 10 minutes.”

Even today, Stout is not nearly the ft- test racquets player out there. He doesn’t warm up obsessively or stretch for hours after a match. “Gym? I don’t think he knows where the gym is,” Briers said. “He doesn’t even know anyone named Jim.” He’s sufered cramps during a couple of long racquets matches. He has had a few inju- ries—wrist, neck, ankle—and two years ago he tore his left knee playing squash just before his world championship defense in Philadelphia (he did rehab three hours a day that week and recovered). His diet is notoriously bad. While playing in the Public Schools Championships, Stout was known to subsist on Häagen-Dazs. He eats Froot Loops for breakfast. Loves choco- late. He smokes.

Underneath the lackadaisical facade is a passionate, proud player. He can glare after a poor call. He has snapped racquets after a loss. He wants to not just win but win decisively.

Of court, Stout is personable, fun- ny, warm. “If he got any more laid-back, he would have a mattress strapped to his back,” Briers said. He happily gets on all four diferent courts at the R&T with play- ers of any level. “He is patient, humble, gen- uinely loves the games,” Larken said. “It’s unique. A world champion and yet he’s a good teacher.”

A few years ago Stout took a steep bet that he could get to 100 in a squash match against an A player at the club, even while sportingly giving him a 98–0 lead. He won 100–99.

James Zug is the author of six books, including Squash: A History of the Game. His writing on sports has appeared in The Atlantic, The Wall Street Journal, the Daily Beast, and VanityFair .com.

Featured in Racquet Issue No. 3