Bill Sullivan 2013

In New York City they tear down buildings with alarming frequency. No matter how long you’ve lived here—seventeen years for me—you never fully get used to it. The other week, I ran an errand in a part of town Ihadn’t visited for a while, and when I came out of the subway, I was met with a gaping hole where an entire block of low-rise stores and restaurants had been. The big-money people were in the rubble with their cranes and workmen, digging a foundation for a luxury condo. There are no sacred sites in New York, either. Preservationists still carp about the demolition of the old Pennsylvania Station, in 1963, and it took a former first lady to save Grand Central Terminal. All that grandeur might today be a bank branch with a lobby of glitchy ATMs. ¶ Still, for reasons as random as they are heartening, some historic buildings survive on. Even as they go unloved and take up valuable acreage. Such is the case with Forest Hills Stadium.

When it was built, in 1923, it was considered the first tennis stadium in America. For much of the 20th century Forest Hills was the mecca of the Western tennis world. The U.S. National Championships and its successor the U.S. Open was played there sixty-one times. It’s where Althea Gibson broke the tennis color barrier in 1950 (and won in ’57 and ’58), where Rod Laver capped his Grand Slam in 1969, where Manuel Orantes upset first Guillermo Vilas then cocky Jimmy Connors in the still-marveled-at ’75 Open. Ashe, Borg, Budge, Court, Evert, Gonzalez, Goolagong, King, McEnroe, Navratilova— they all played there too.

More recently, the stadium became home to a colony of feral cats. It was basically a concrete ruin in the backyard of a tennis club.

That club, the West Side Tennis Club, hosted the Open and owns the stadium. Tennis clubs are viewed as playgrounds for the well-heeled and are, by extension, wellheeled themselves. Not the West Side Tennis Club. You get the impression it’s been in gentle decline ever since the tournament pulled out in ’78 for nearby Flushing Meadows. The members are endearingly honest about this. You visit them in their sprawling Tudor-style clubhouse and they’re like, “We wanted to create a museum here to display our history but we don’t have the money. Hey, do you or your wife play tennis? We have a deal for junior members under 34.”

It would be a burden for any club to maintain a near-century-old steel-and-concrete Romanesque stadium that hasn’t been used for a significant tennis event since the Tournament of Champions in the ’80s. It languished. Three times the club members took a vote to sell it to developers. In 2011, in a last-ditch salvation effort, someone proposed the stadium for landmark status, but the Landmarks Preservation Committee, noting the crumbling facade and extensive water damage, rendered it “ineligible at this time.”

Then something remarkable happened for New York. The real estate buzzards who’d been eyeing the place were chased away. Too many club members felt the stadium was too much a part of their history and agreed to save it (or rather, they never reached the supermajority vote needed to sell). That left them searching for a savior to bring it back to life as you might an ancient amphitheater. Strangely, that savior was a rock promoter.

There’s a parallel history of Forest Hills as a music venue, it turns out, as rich in some ways as the tennis stuff. Name just about any important artist from the ’60s and early ’70s, and they played Forest Hills. And yet it doesn’t make anyone’s list of famous venues, even if the list is kept to New York. When I asked Craig Finn, the lead singer of the Brooklyn-based Hold Steady and a student of rock culture, why that was, he chalked it up to a lack of continuity. “A lot of the places that are famous are continual,” Finn said. “Linda Ronstadt played the Troubadour, but so did Nirvana. There’s a gap in the Forest Hills story.”

As Roland Meier, the president until recently of the West Side Tennis Club, put it to me, “Two generations don’t know about Forest Hills.”

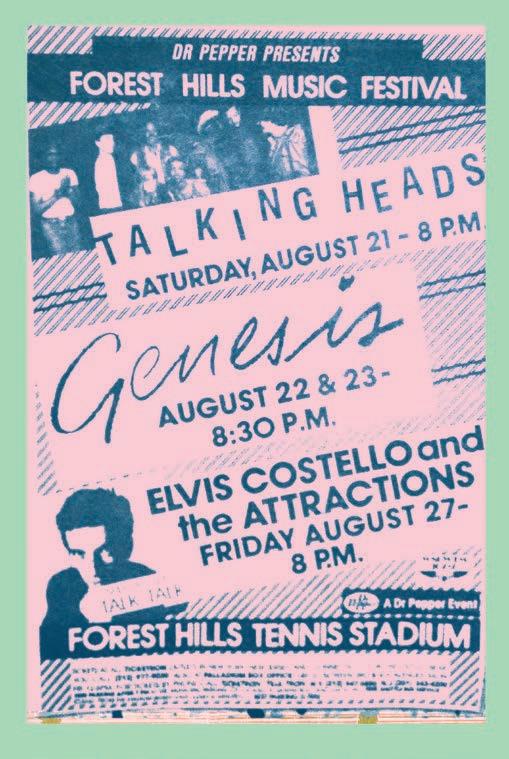

The last truly great concert to take place at Forest Hills was probably the Talking Heads, in ’83. But let’s start where so much of rock history does, with the Beatles. The Shea Stadium shows in ’65 get all the attention and have since become lodged in the city’s collective imagination, but the band performed at Forest Hills a full year before that, on Aug. 28 and 29, 1964.

This was just months after the Ed Sullivan appearance, at the frenzied, pants-wetting height. During an interview with a New York radio station that trip, Lennon and the interviewer had a discussion about waving, and whether the Beatles were allowed to wave down from their hotel to the fans amassed on the street. “They won’t even let us,” Lennon said of the police, because they’re “worried that it will sort of incite them.” That’s how crazy things were, a wave from eight stories up was too explosive. Can you imagine what the little stadium was like? The interviewer asked Lennon how the band managed the chaos. At Forest Hills the night before, an eight-foot-high fence topped with barbed wire was used to keep 16,000 fans from the stage. One fan, Lennon said, got through to George anyway: “I could hear wrong notes coming out. He was trying to carry on playing, you know, with a girl hanging ’round his neck.”

There were concerts at Forest Hills before the Beatles. The earliest one anyone seems to remember was the Kingston Trio, in August of 1960. Judy Garland played the stadium the following July, and Joan Baez came in August of ’63, joined for two songs, “Troubled and I Don’t Know Why” and “Blowin’ in the Wind,” by Bob Dylan (more on Dylan later). The Baez concert was part of the Forest Hills Music Festival, which wasn’t a single event but a lineup of shows on weekends throughout the summer. The festival ran every summer for more than a decade, into the ’70s.

The bills were wonderfully diverse, like radio at the time. The 1970 festival featured Sly and the Family Stone, Leonard Cohen, Janis Joplin, the Band, and the 5th Dimension. In the summer of ’67, the Monkees performed with Jimi Hendrix opening. The show has acquired a degree of infamy because during the preceding tour dates, the Monkees’ teenybopper fans had booed Hendrix, or actually chanted “Davy!” during his set, which is the same thing, and by the time Hendrix got to Forest Hills he’d had enough. He flipped off the audience, walked off stage, and quit the tour the next day.

That’s the thing you notice about Forest Hills when you dig into the history: Concerts there were charged, or else they pop up in the culture in strange ways. The Rolling Stones played Forest Hills in ’66. Four decades later, the event featured in an episode of Mad Men, when Don and Harry Crane go on a fruitless mission to Queens to sign up the Stones for a Heinz Beans jingle. Hanging backstage in his pointy tie and stiff Bryl- creemed hair, Don gets talking to a young female Mick enthusiast, the generation gap hanging between them like a yawning crater.

Another Forest Hills show that still comes up is Simon & Garfunkel, who played two gigs on a July weekend in 1970. They were neighborhood boys, graduates of Forest Hills High, so the show was a homecoming. “Only U.S.A. Appearance This Season!” the poster touts. It turned out to be an ending. Their partnership fraying, the duo broke up right after. Setting aside the later reunions, Forest Hills was the last Simon & Garfunkel concert.

Weirdly, it could happen again, forty-six years later. This time with Simon alone. In a recent interview with The New York Times, the 74-year-old said he saw himself “coming towards the end” of his musical life. “It’s an act of courage to let go,” Simon said, using deathbed language. “I’m going to see what happens if I let go. Then I’m going to see, who am I?”

He’s been on tour supporting his latest (and last?) album. He sometimes sleeps fifteen hours to recover, and requires off days to rest his voice. The final dates of the tour were June 30 and July 1—at Forest Hills.

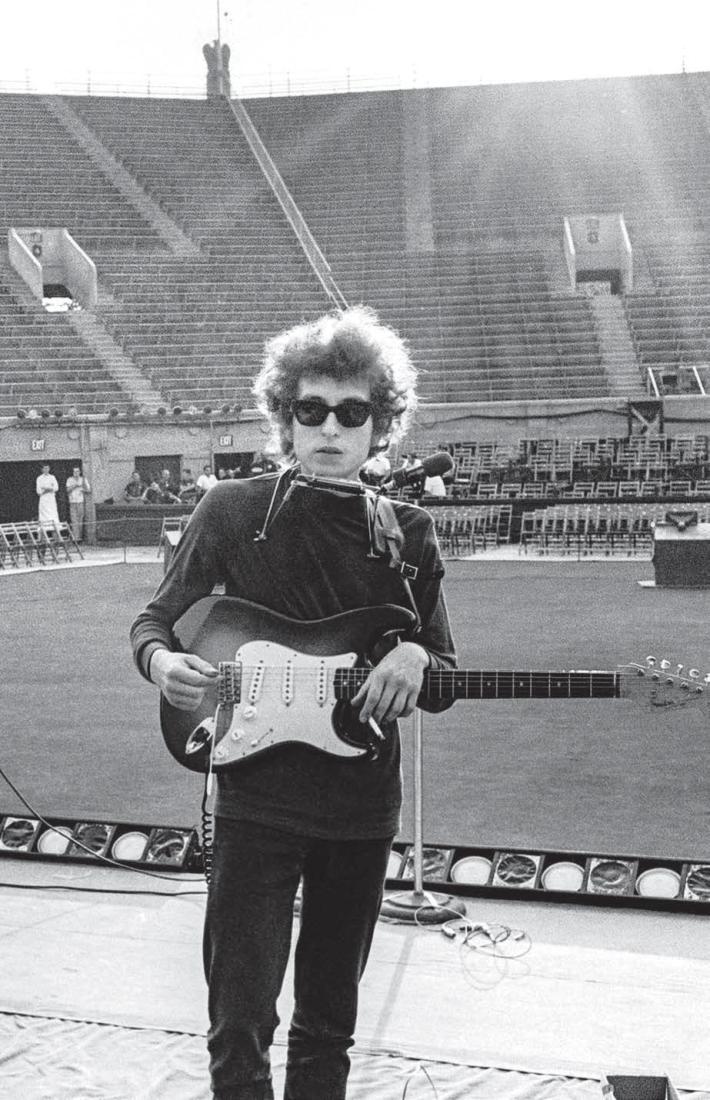

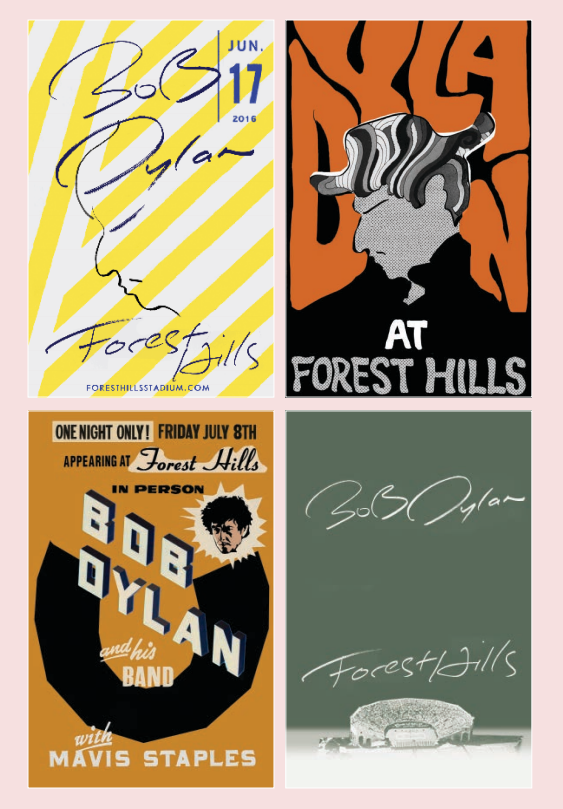

Early designs for Bob Dylan’s 2016 Appearance at Forest Hlls Stadium.

bill sullivan

“It’s a magic place.”

Mike Luba is standing on a metal stage, looking out at center court and the stadium that surrounds it like a massive concrete horseshoe. A tall, 40ish man who brokers million-dollar business deals, Luba dresses like a roadie: ball cap, work boots, loose dark pants, and a short-sleeve black T-shirt over a long-sleeve white T-shirt. Since he and his business partner, Jon McMillan, began promoting concerts at Forest Hills in 2013, Luba has relished giving tours. You can tell he sees the place as his giant sandbox.

“When we got here there were six-foot trees growing out of compost piles,” he says, gesturing. He describes the splintered benches that hadn’t been replaced in seventy years, the green paint flakes scattered like confetti, the junk stashed under the stadium by three generations of club maintenance crews.

“The paradox of this place,” Luba tells me, “is that it’s simultaneously a priceless gem, and when we started, it was also a complete dump zone.”

Luba first visited in 2012, when he was working with the French band Phoenix, who were playing New York and looking for an off-the-wall venue. Luba had played tennis in high school on Long Island, and he knew about the stadium’s music and sporting history. He called the pro shop and talked to Bob Ingersole, the head pro, who invited him out. This was just after the club had again voted not to sell. Luba was horrified but intrigued. He returned the next day with a structural engineer. “This looks like a complete bombed-out war zone with feral cats and raccoons,” the engineer told him.

“But if someone was going to drop a bomb on me and I was in Queens, this is where I would come to hide out.” That was enough.

It should be said that Forest Hills attracts promoters with crazy ideas. Ron Delsener, the granddaddy of nattily dressed music sharpies, who inspired Bill Murray’s character in Rock the Kasbah and who once said of his work-family balance, “I have a wife; I sacrificed her to this business,” cut his teeth at Forest Hills in the ’60s. In the ’80s, John McEnroe and Vitas Gerulaitis teamed up for MusiCourt ’82, a charity event that mixed tennis and rock and yielded a sublime photo of McEnroe, Gerulaitis, Carlos Santana, and Meat Loaf shaking hands at center court. In the ’90s, reggae promoters threw festivals here that the tennis club thought were going to last an afternoon but instead lasted whole weekends.

As for Luba, he couldn’t get the stadium out of his mind. The Phoenix gig fell through, but he kept telling bands about this incredible place out in Queens, a tennis stadium, where the Stones played, where the Who played. In 2013, he brought one of the guys from Mumford & Sons out. It was a cold, nasty day, but young kids were hitting on the club’s courts. Two of the Mumford guys are from Wimbledon. If you can get it functional, Luba was told, we’ll come play.

He raised money privately, including from his old high-school tennis teammates, hired a crew, and got to work. Ripped out the rotted benches, stripped the concrete to the rebar, made over 3,000 individual patches to the facade. He and his partners spent $5 million without any ownership transfer, just a licensing agreement with the club that they could hold concerts for a period of years.

“It’s a complete passion-project boon-doggle,” Luba says. “But it’s been one of the greatest projects I’ve ever had the chance to be involved with.

Because when the place gets going, it’s as good a concert venue as anywhere in the world.”

This is the sort of line you expect a rock promoter to say, but with Forest Hills, it’s not that big a stretch. I’ve never seen a band at Madison Square Garden—or any other arena, for that matter—without feeling, on some level, that I was part of the corporate-entertainment-industrial complex. You don’t feel that at Forest Hills. The place is like no other, notable in a number of ways— for one, the acoustics, which people remark on time and again. “A crystal-clear sound,” the critic Robert Palmer wrote of a Talking Heads show back in ’82. “She was aided by well-balanced amplification,” a reviewer remarked of Barbra Streisand in ’64. Beatrice Hunt, the chair of the archives committee for the West Side Tennis Club, said that even in its sorriest state, she and other members liked to take guests out to the stadium to volley, because balls echoed inside the horseshoe with this incredibly resonant thwock. There’s also the resonance of history. Walking around, you get a sense of what tennis—and pro sports, generally—was like before everything went big-business. The intimate scale, compared with modern stadiums, is startling. In Carnival at Forest Hills, sportswriter Marty Bell’s account of the ’74 Open, Bell wrote that holding the championship there was like “playing the Super Bowl in a high-school stadium.” They used to hand-paint the match results on a huge board, which is still there today. The corporate boxes sold for between $750 and $990, or less than what a courtside seat might cost you in 2016 at Flushing Meadows.

Craig Finn said that more than as a musician, he was stoked to play Forest Hills as a tennis fan. His band opened for the Replacements in 2014. “As a kid I was really into Borg,” Finn said. “As I’ve gotten older, and especially when I moved to New York, I’ve gotten into McEnroe.” Opening for the Replacements at Forest Hills, Finn said, was a full-circle thing. “When I first heard about the Replacements, I was playing tennis at a club my parents belonged to, the Interlachen Country Club in Minneapolis. This kid asked me who my favorite band was and I said the Ramones. He said, ‘If you like the Ramones, you’ve got to check out the Replacements.’ And then years later I’m in a band opening up for the Replacements at a tennis stadium.”

Finn loved taking the subway to the gig, and hanging out in the Rose Garden, a little fenced-in area adjacent to the stadium where the fans used to relax and have sandwiches between matches. “It’s quite a bit nicer than a rock club,” he said. “The things you associate with tennis were transferred to a rock show.”

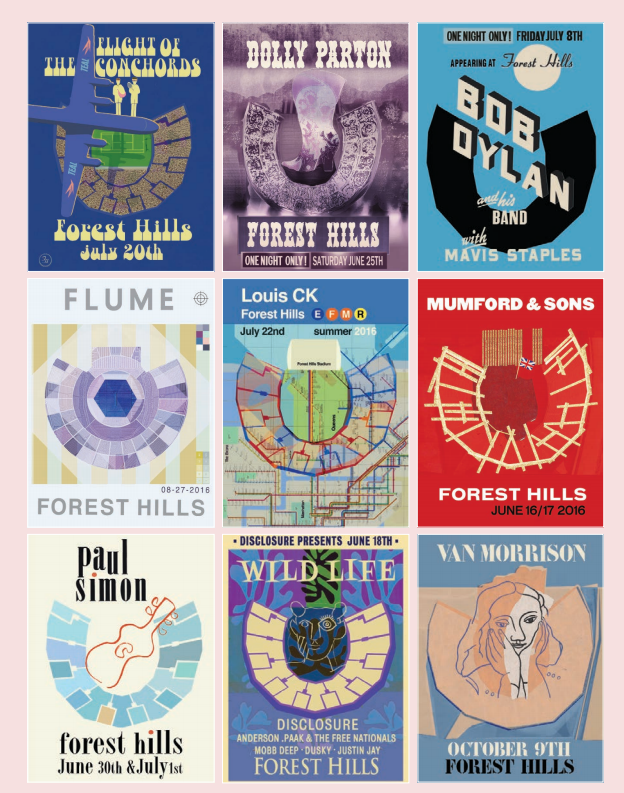

Luba says musicians love playing Forest Hills—among them, Van Morrison, the Alabama Shakes, Drake and Lil Wayne, and the Replacements, so far—which you might take as another promoter’s line that’s also probably true. Musicians, the good ones, have always appreciated their history. Luba is carrying on the tradition of diverse lineups, and bringing back acts that played Forest Hills years ago. “Last year, getting the Who ticked one off the box,” he says. This summer he’s bettered himself, returning Paul Simon, and the biggest headliner yet for the revamped stadium, the man who gave the most famous concert at Forest Hills, fifty-one years ago: Dylan.

In New York in the dog days of August there sometimes comes a cold snap, a sudden jolting intimation of winter. Marty Bell noted it in his account of the ’74 Open: “In just one day, the August heat had become November cold. It was as if the tournament had made a sudden shift to Iceland.” The same freakish weather descended on the city on Aug. 28, 1965, when Bob Dylan and his band performed at Forest Hills.

Here’s bassist Harvey Brooks recounting the night: “It was kind of cool, windy, you know, and like from my point of view, I’m standing on stage, it’s dark, and at that time the audience was back”—Brooks is referring to the unusual setup at Forest Hills then, the huge space between the performers on stage and the audience in the stands, because the court was left empty to protect the grass— “so we were playing to this audience that were way back, that we couldn’t really see.”

I’ve never seen a band at Madison Square Garden— or any other arena, for that matter—without feeling, on some level, that I was part of the corporate-entertainment- industrial complex.

You don’t feel that at Forest Hills.

The Replacements perform at Forest Hills Stadium in 2014. p squared

I’ve never seen a band at Madison Square Garden— or any other arena, for that matter—without feeling, on some level, that I was part of the corporate-entertainment- industrial complex.

Al Kooper remembered the foul weather too, in his memoir Backstage Passes and Backstabbing Bastards. He called the rain earlier that day “God’s little preview of what the night held in store.”

Forest Hills was the first concert after his famous Dylan-goes-electric set at the Newport Folk Festival a month earlier. Let’s spare another retelling of the most dissected forty minutes in rock history, one whose central controversy—the folk crowd’s sense of betrayal after their hero plugged in his guitar—seems quainter with each passing year. But suffice it to say, the musicians in Dylan’s band had reason to see the bad weather as an omen, because unlike the surprise of Newport, the Forest Hills audience knew what was coming. They’d had a month to work themselves up. “America was ready for hand-to-hand confrontation with its reckless idol,” Kooper wrote, “and Forest Hills would prove to be the battleground.”

As he had at Newport, Dylan first performed a solo acoustic set, which only thickened the anger. They booed and catcalled. Jack Newfield, reviewing for The Village Voice, called the audience “riotous.” Backstage, Dylan’s band, which also included Robbie Robertson and Levon Helm, watched with knee-buckling fear. “We nearly shit our pants,” Brooks would later say. Dylan, cool and unwavering, called the musicians into a huddle during intermission, warned them it was going to be a “circus,” and told them to play through it no matter what.

There’s still debate about whether the audience “rushed the stage” that night. When the Times used that language in an article a few years back, a reader wrote in to say he was there, and that no, it was more like “three people running in circles around a tennis court trying to avoid security guards.”

Brooks remembered more onrushers, and one of them getting to Al Kooper and wrenching his stool out from underneath him so he fell over. It’d be hard to argue the intent wasn’t violent. Brooks looked to Dylan, who motioned to just keep playing. When the band closed with “Like a Rolling Stone,” released weeks earlier and already a hit, the crowd booed and sang along at the same time.

It’s been years since people have cared that passionately, to the point of near-rioting over a musician’s artistic choices. When Dylan performed at Forest Hills this summer, people just hoped he’d sing his classic tunes in a voice that was fairly intelligible. (In typical Dylan fashion, he didn’t give the audience what it wanted.) Nonetheless, having him perform at Forest Hills again was meaningful, for Luba and for the West Side Tennis Club. It signified that the stadium is really back. Roland Meier, the former club president, said the place feels alive again, with members gathering for barbecues at the clubhouse during concerts. Even pro tennis has returned, with World Team Tennis playing matches this summer.

Even with the repairs—and the stadium, today, looks ten times better than it did for the 2013 Mumford show, with actual seats where there’d been naked concrete—there remains a wonderful ancientness, a sense of being out of time and place. Seeing that arched stone facade rising from a Queens neighborhood is a little like the feeling you get in Rome when you turn a corner and before you is a colossal engineering marvel dating back to the days of chariots and the Empire. The new Barclays Center over in Brooklyn may have private lounges, a retail concourse, and a Junior’s, but you don’t feel the open-air thrill of having taken over Pompeii for the night.

Forest Hills, said Meier, “represents history, a certain style.” Thinking of how close it came to being crushed, he shuddered: “It’s mind-boggling that we could’ve turned this into a parking lot and condominiums.”

Steven Kurutz is a features reporter for the New York Times and the author of Like a Rolling Stone: The Strange Life of a Tribute Band.

Featured in Racquet Issue No. 1