The Silver Belles of the National Senior

Women’s Tennis Association Still Want

to Win—Because They Still Can.

Liane Bryson is feeling good. Really good. She’s just come off the court after walloping Brenda Carter in the semifinals, 6–2 both sets, slicing shot after shot and watching Brenda run after them, flailing around like a 5-year-old at her first tennis lesson. Now Liane is sitting under the awning at the courtside patio, legs wide, elbows on her knees, her sweaty blond bob clinging to the nape of her neck. She takes a sip from a water bottle, adjusts her visor, and waves over her friend Dori Devries.

“I see the new hips are working out!” Dori calls as she walks over.

“So far so good!” Liane says and pats her legs.

She’s had three hip replacements in nearly as many years, and the recovery time has really cut into her training schedule. She’s got her personal trainer, her daily practices, and this boot-camp class she’s been taking back home in San Diego where they make you run up and down 100 stairs at a time. By the end, Liane just wants to die. But she has to do it. She wants to win a national tennis championship. Liane moved into the 70-year-old age bracket this year, and boy, the competition is tough.

For a week in early July, Forest Hills has been overrun by a hundred women like Liane: tall women, squat women, women with children, women with grandchildren, women who remember the Nixon administration, all them out there grunting and snorting on the club’s grass courts, their arms deeply tanned, their knee braces affixed just so, their hair as white as their skirts. This is the National Senior Women’s Tennis Association, and these are the best players around. They’re out there to win, they’re eager to tell you, because they still can.

If you’re too young (bless you) or too amateurish (aren’t we all?) to worry about what happens to competitive tennis players after they turn 30—Serena and Venus notwithstanding—let me give you the rundown: You’ve got a few years’ worth of leeway if you’re lucky, but eventually your options are to retire, join a local league, or embark on the so-called senior circuit, which holds tournaments for players of varying experience levels all over the world. Your local country-club goers—you know, the women who spend more time running errands in their tennis skirts than actually playing the game—might enjoy a Category III tournament. But this is Category I. Many of the women at Forest Hills this weekend competed professionally in their younger, wrinkle-free years. Others, like Liane, just happen to be very good—and very, very dedicated.

There are men’s senior tournaments, too, of course. But the livelier ones, the ones with dinner parties and John Mellencamp concert outings and five players crowded into one Airbnb rental, are the women’s. “I played my first national when I was 55—I’m 71 now— and I met a lot of the same people who are here today,” says Brenda Carter, the player Liane just beat. “That’s what really brings me back: the people.”

Brenda has short white hair and a soothing Georgia accent, although she’s lived most of her life in South Carolina. She’s pulled up a chair alongside Liane on the patio now; the two women, when they’re not competing, are actually good friends. Brenda says they met on the tennis court in their mid-20s, although Liane isn’t so sure.

“She says we played together,” Liane says, then leans in and lowers her voice, “but I don’t remember her.”

“We played for a year and a half together!” Brenda feigns offense. Liane laughs and shakes her head.

They, like most of the players here, have long gaps in their tennis careers—years, sometimes entire decades, when school or children or work forced them to put the game aside. It’s still happening now; there are only seven players in the 30-year-old bracket, and one of the 40-year-olds just returned to the sport after taking nine years off to raise three kids. Meanwhile, there are more than two dozen 70-year-olds. But even within the advanced-age groups, Brenda says, there’s a marked difference between those who had access to tennis clubs and coaches and those who didn’t. The split isn’t down economic lines but instead who benefited from the implementation of Title IX, the 1972 law that said schools couldn’t exclude women from academics or sports.

“Title IX was the beginning of the real training,” says Brenda. “The difference in the level of play between even just the 60-yearolds and us is immense. They had college scholarships and trainers. We didn’t have anything.”

When Brenda was in college, there was no such thing as a women’s tennis team; she only knows the game because her brothers played. After she graduated high school in 1964 she had nowhere to play, so she gave it up. Liane picked it up because her family belonged to a tennis club in Germany, where she grew up.

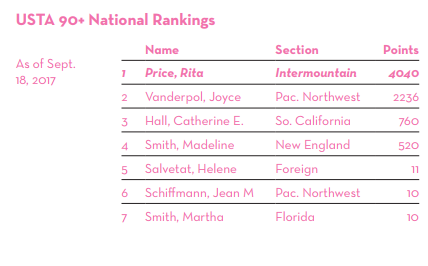

Rita Price didn’t even have that. Rita is 91 now and didn’t discover tennis until middle age; she took lessons at her local YMCA in Colorado and has since won so many championship titles she’s started giving away the gold balls awarded as trophies because she has nowhere left at home to put them.

Rita is the grande dame, the Meryl Streep, really, of women’s senior tennis. “Have you talked to Rita?” players keep asking me throughout the tournament. “You absolutely have to talk to Rita.”

Rita loves tennis with a passion so intense it’s hard to talk to her without falling for the sport too. She’ll reenact past matches for you with big hand gestures, explaining each shot and how she won or lost. Rita’s on a fixed income, and a few years ago she sold her house and moved in with a friend so she could afford to travel to tournaments. “This all costs money,” she says. “But now I can say I’ve been to Turkey. New Zealand. Last year I made $1,000 in Austria!” She’s not sure why she’s so good at tennis; she used to be a tap dancer in burlesque shows, and her theory is that all that footwork translated well to the court. When she was inducted into the Colorado Tennis Hall of Fame in 2003, Rita thanked Franklin D. Roosevelt for creating the Works Progress Administration, which funded the first dance classes she ever took.

Rita isn’t playing at Forest Hills this year; technically, she’s too old. Age groups are divided by decade, and the last age bracket in this particular championship is 80. She had the same problem at the clay-court championships in Houston a few months earlier; that time, a second 90-year-old agreed to play her and the officials called their two-person singles match a bracket. Rita won.

But today, she’s just here to watch. That’s probably for the best anyway, because the heat today is stifling. There’s no shade on the courts, so the players carry bags of ice and cold towels to help them cool off in between sets. Rita sits on the patio a few yards away from Brenda and Liane, in hoop earrings and high-heeled rhinestone flip-flops, sipping rosé with her friend Lurline Fujii. Lurline flew all the way from Honolulu to play in the tournament but didn’t do so well. She’s 76 now and her Parkinson’s is getting worse.

“When I swing fast, on a serve, I can still do it.” Lurline moves her wobbly right arm through the air to demonstrate. “But if I go slower, who knows where the ball will go?”

She and Rita compare ailments for a while, pausing occasionally to watch one of the matches going on in front of them, the 60s semifinals. Rita doesn’t know one of the players, but the other one, she says, is just fantastic: Susan Wright. Susan just turned 60 (Rita used to play doubles with her dad), which puts her well into the post–Title IX crowd. Her first coach, Dennis Van Der Meer, also coached Billie Jean King during the Battle of the Sexes.

“Just look at her,” says Rita as Susan prepares to serve. “Oh, she’s good!”

And she is. She’s slender and agile and has the long, practiced swing of someone who’s been doing this all her life. Susan started playing tennis when she was 8 years old; after high school she spent three years on the pro circuit and played four Grand Slams. But then she quit. For 25 years. She started again at the urging of her father and has been playing nationals now for almost as long as she spent retired. Susan is playing both singles and doubles today and is beating everyone so soundly that she keeps advancing without having to play the third set. She’s a Mary Kay cosmetics consultant and her brown hair bounces with every swing.

There’s a focus and intensity in Susan that I’ve seen before in other professional athletes, but rarely in an amateur. In fact, nobody at Forest Hills seems very nervous. Oh, there’s a sense of determination, sure— they’ll play tennis until they can’t walk anymore—but it’s tempered by the unavoidable fact that had these women gotten the shorter end of the genetic stick, they might not be able to compete at the level they do.

“You really just never know how long you’ll get to keep playing,” says Allyson Bolduc, a 70-year-old doctor from Vermont who’s joined Liane and Brenda on the patio. Every time Rita talks about future tournaments she plans to play, she adds, with a certain fatalism, “Well, if I’m still around.”

I have to admit, it’s a little unsettling to see Life Alert’s target audience out there for hours, running around in 95-degree heat. A few years ago a player sprained her ankle, and when the ambulance arrived the EMTs looked at one another like, what are all these little old ladies doing out there in the sun? They tried to make everyone go inside, but the women informed them they were elite athletes competing for a championship title and could take care of themselves, thank you very much.

The more I watch these women, the more I wonder if maybe age and athleticism aren’t as incongruous as I always thought. These women are tough. To prepare for the tournament, Susan was in the gym an hour and a half nearly every day. Weights, stretching, cardio. Then out on the court for a few hours more. Other players swim. Some have taken up yoga. Liane has her trainer and boot-camp class, while Lola O’Sullivan, who’s 79, plays full tennis matches twice a day. Rita does tai chi to improve her balance.

Susan’s training must’ve paid off, because she barrels through the semifinals, 6–3 and 6–0. The following day, a Sunday, she does it again, winning her age bracket in both singles and doubles. Liane doesn’t have the same luck; she loses in the singles finals. In doubles, she and her partner come in third.

After Forest Hills, Susan and her doubles partner will travel on to Philadelphia to play another grass-court tournament the following week. A lot of the women are going, actually. The last matches are still being played, and already they’re talking about the next tournament: who’s seeded ahead of whom, who has room for an extra passenger in her rental car. Lola, in particular, is especially animated; she should be second seed in the 70s, she says, but instead the Philadelphia organizers have ranked her third. She fumes about it for a while, then pulls out her phone to email the tournament officials.

“I’m going to give them a piece of my mind,” Lola says. She types angrily for a few minutes, then looks up.

“How do you spell ludicrous?” she asks. Rita isn’t going to Philadelphia. Instead,

her children and grandchildren are flying to New York and the whole family is going to see a Broadway musical. Rita has also scored tickets to a concert for a band she’s never heard of but hopes her teenage granddaughter will like. “My Morning Jacket?” she reads the name off her tickets. “Are they a rock band? I like rock bands.”

She returns the tickets to her purse and then settles in to watch another match, the 50s singles. One of the players, Libby Kreutz, is new to senior tennis. She’s never played a tournament before. Libby is a documentary filmmaker in Manhattan and had taken a day off work just to see if she could do it. “It was a lark. I figured I’d play a few sets and lose and that would be it,” she says. Instead, she kept winning. She took another day off work. Then another. Libby hadn’t trained, only owned one racquet, and had to run across the street to the dollar store to buy an extra polo shirt when she advanced yet again but had run out of clean tennis whites. She made it all the way to the consolation round’s semifinals before losing. When it’s over, Libby walks off the court and heads for the clubhouse’s ice machine so she can refill her water bottle. “I can’t believe how intense this was,” she says. A sweat bead runs down the arch of her nose and falls to the ground in front of her. “I really should take this game more seriously.”

Noel Camardo is a photographer based in Brooklyn, NY, his work focuses on everyday life in America.

Claire Suddath is a writer for Bloomberg Businessweek. She played tennis once and it went pretty well.

Featured in Racquet Issue No. 5