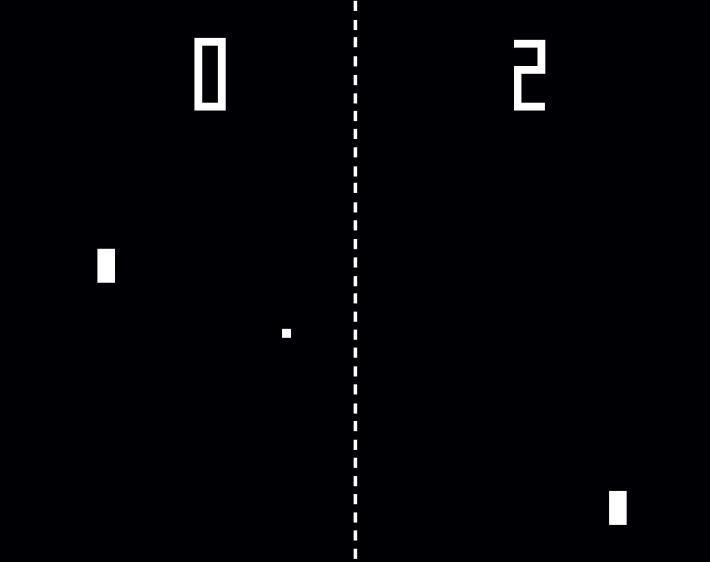

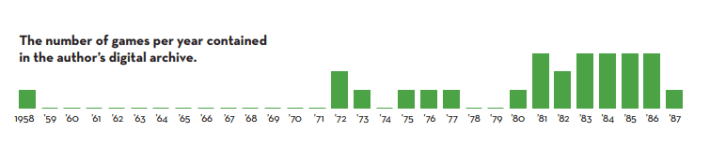

Two lines and a dot. Or two racquets and a ball. The simplicity of these three elements made tennis an ideal candidate for early computer-game developers. Even abstracted to its most basic geometry, the connection between the digital game and physical sport was clear, and the resulting gameplay, competitive and fun—helping make tennis a recurring subject of video games for six decades. I created the tennnis. org archive to document this persistent role of tennis in the history of video games and to investigate the varied games and design choices made within the genre.

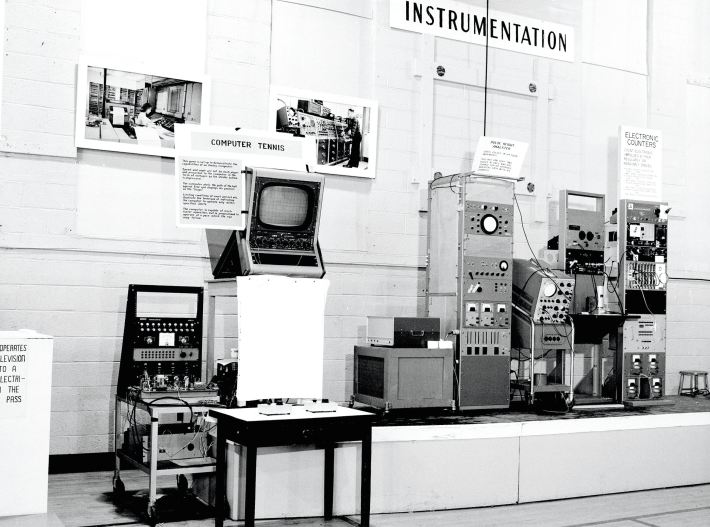

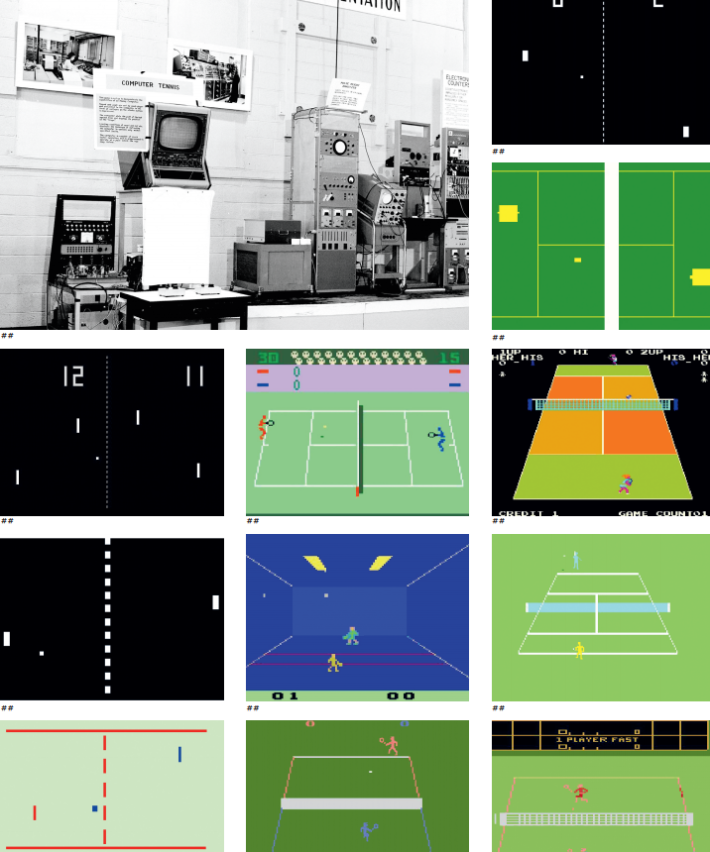

Tennis for Two (the first entry in the archive) was developed in 1958 by William Higinbotham at Long Island’s Brookhaven National Laboratory and ran on a Donner Model 30 computer with an oscilloscope display. Two players took turns controlling the angle of their racquets to aim a ricocheting spot of light back and forth over the net. Most notably historically, Tennis for Two was designed as entertainment for visitors to the lab, making it stand out from other computer hardware demos of the time and securing its place as one of the very first video games.

Using table tennis as inspiration, Allan Alcorn designed the immensely influential game Pong in the early 1970s at Atari. First popular as an arcade cabinet released in 1972, it became a huge commercial success as Home Pong during the 1975 Christmas season. As a dedicated console playable on a television set, Home Pong helped move the primary home of video games from the arcade into the living room and to establish Atari’s rule of the market in the late 1970s and early 1980s.

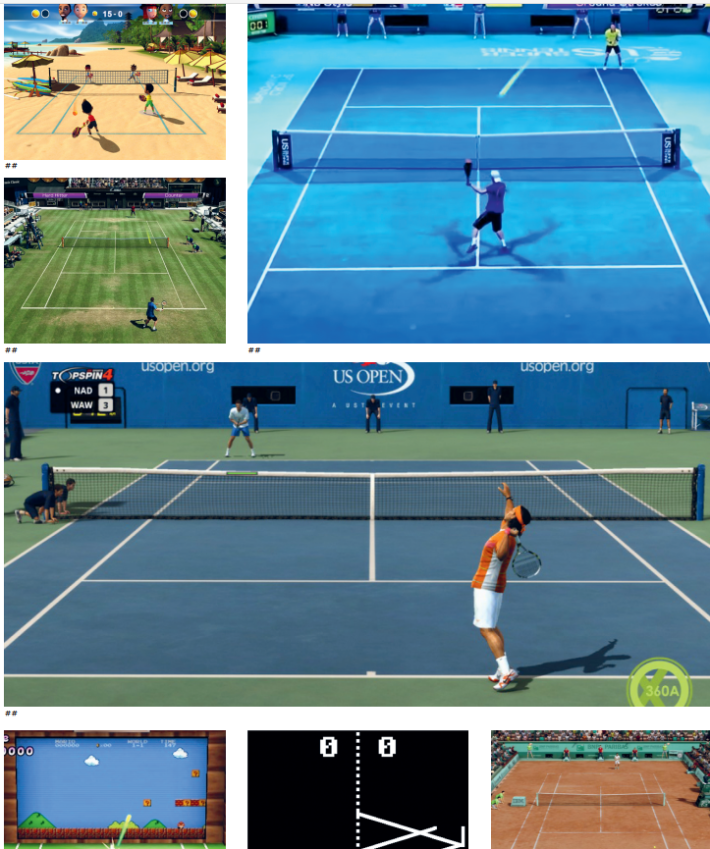

Pong and other tennis video games would be duplicated on nearly every video game platform afterwards. Though graphics, hardware, displays, and controllers have all evolved along the way, the basic game mechanics have remained remarkably consistent. Two lines (or racquets) propel a dot (or ball) across a screen as the moving target of dueling players’ attention. This consistency of mechanics amongst so many other changes has been the most compelling feature of the archive for me. As an animator and designer who works with a lot of large sets of images and data, my eyes are constantly drawn to what changes and what remains the same. Six decades’ worth of video games proved to be a particularly rich dataset in this respect.

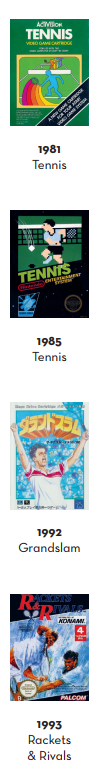

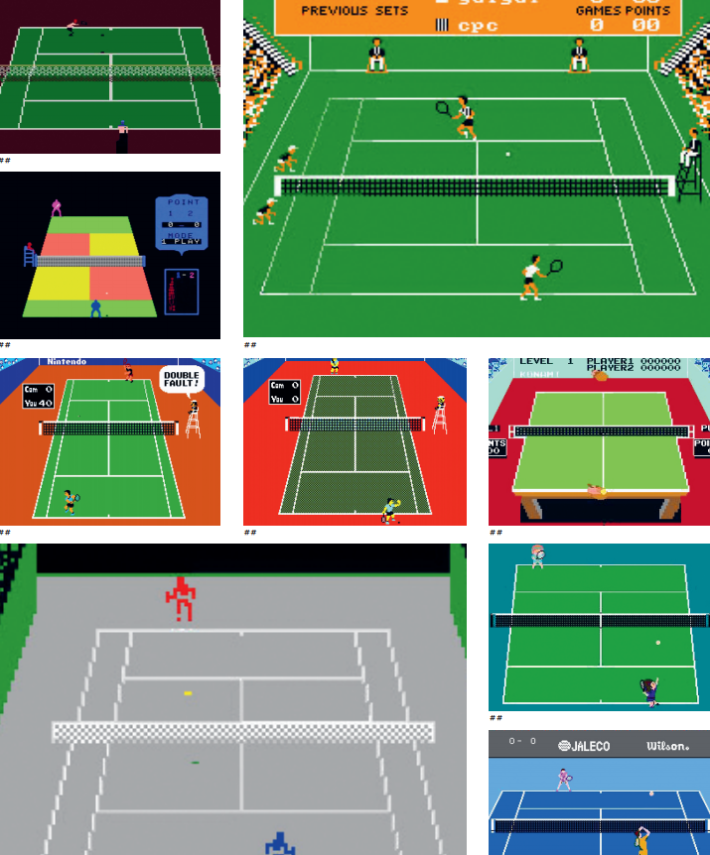

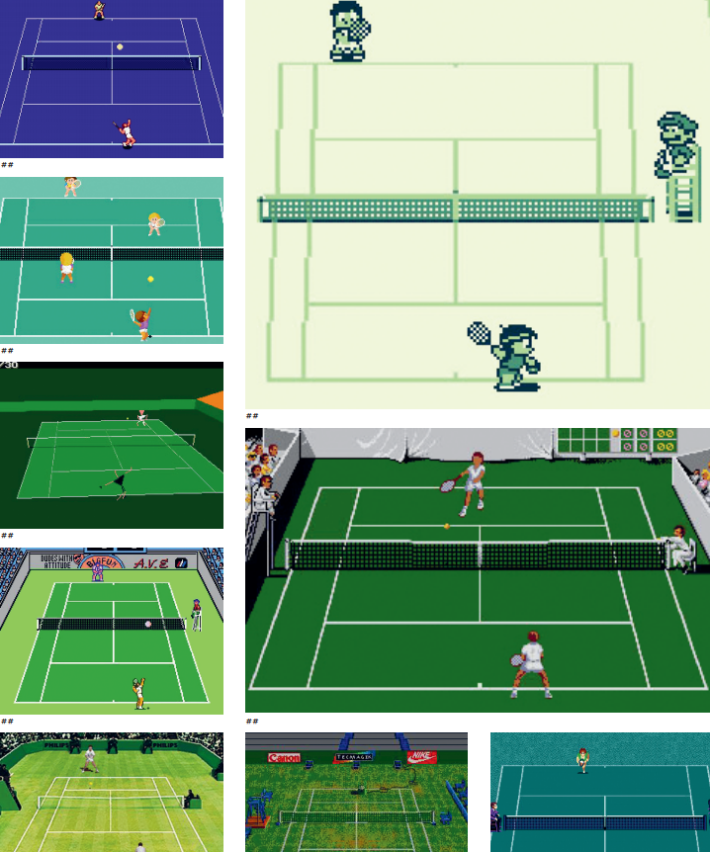

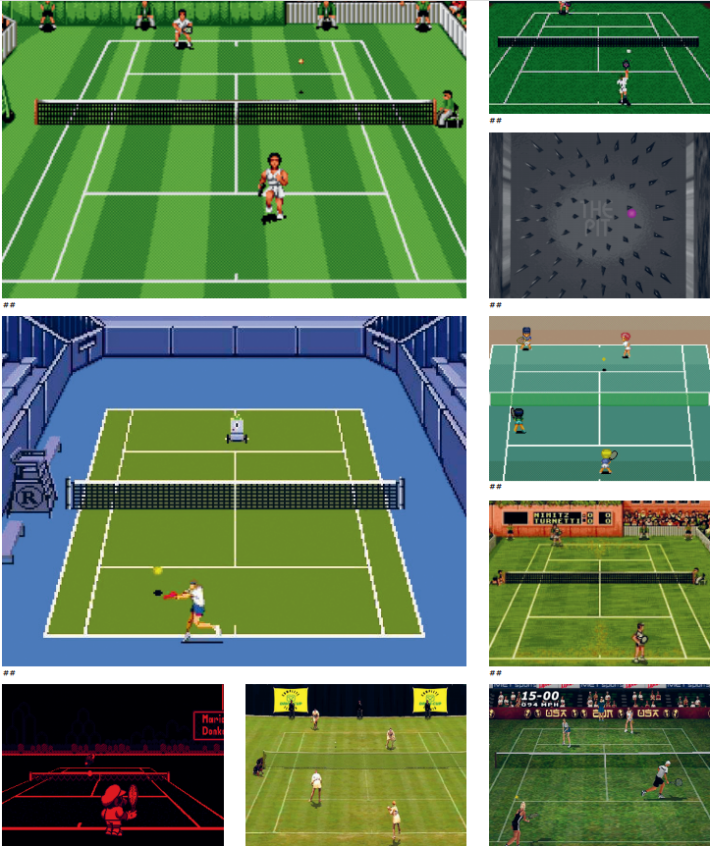

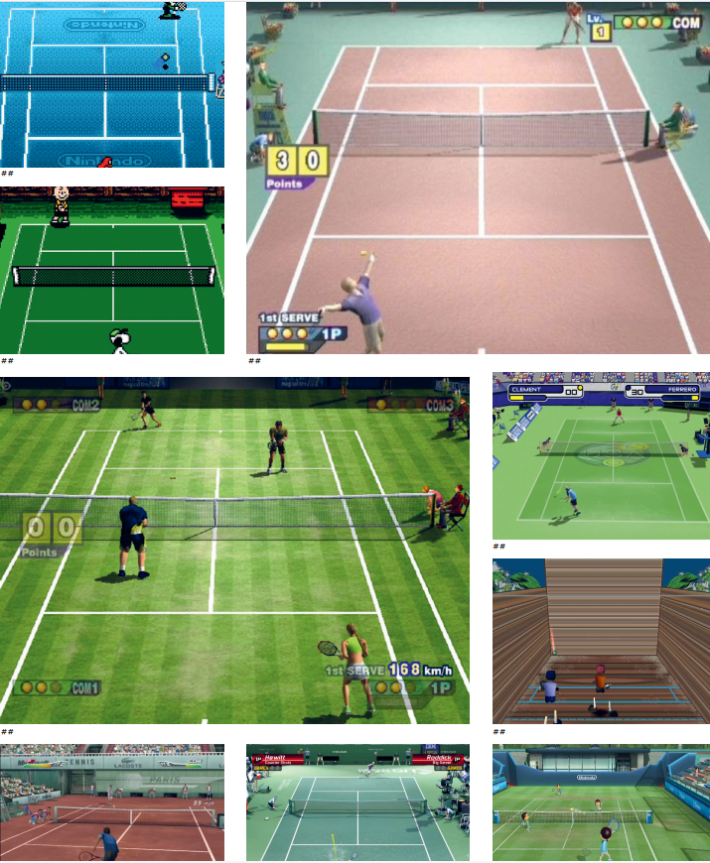

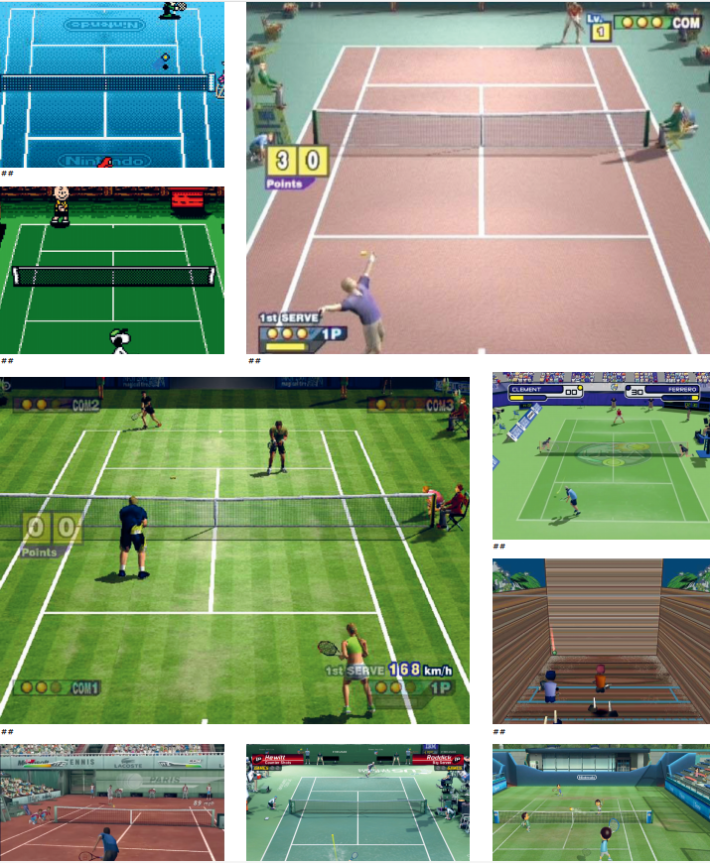

When first looking at the archive, technological advancements form the most visible trend. As more detailed graphics became possible, visuals changed from minimal black and white to solid colors to two-tone pixelated grass to slick gradients and complex texture maps. Also, as consumers’ expectations for three dimensions (versus two) grew, tennis video games reflected this with a progressive tilt of the court, beginning as a flat two-dimensional bird’s-eye map view to a more representational tilt of the court, more consistent with a player’s perspective. Player avatars have also evolved, gaining more pixels and definition with progressive hardware capability.

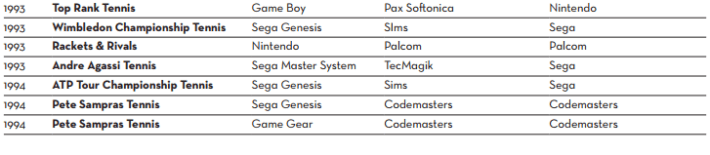

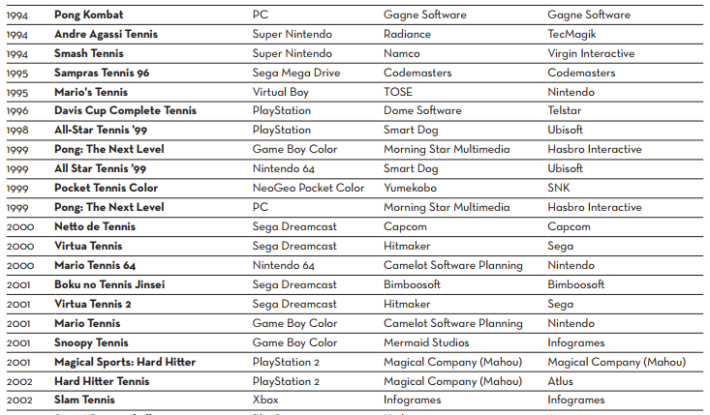

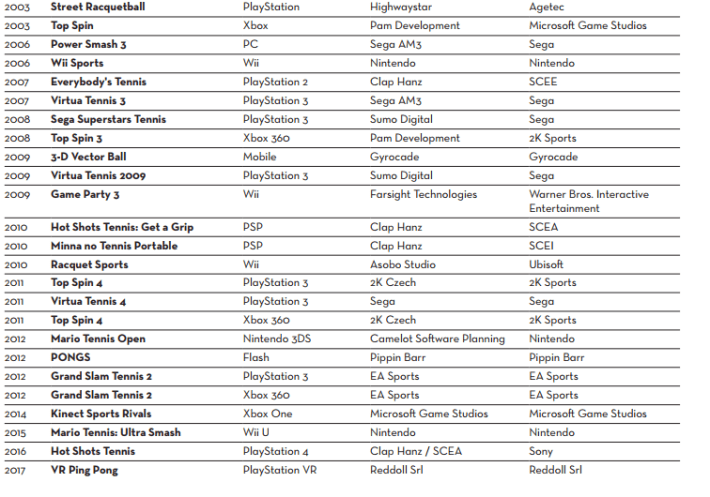

Some visuals, like character designs, have also changed in less predictable ways, shifting between realistic and stylized forms. These variations are not always rooted in technology but often in changing market goals and target audiences. Nintendo and Sega both incorporated their company’s cartoon mascots in games like Sega Superstars Tennis (2008) starring Sonic the Hedgehog and in a series of tennis games published by Nintendo starring Super Mario. Many tennis stars have licensed their names and likenesses to reach their fans and to lend their credibility. Andre Agassi, Pete Sampras, Rafael Nadal, Jimmy Connors, and Jennifer Capriati all have tennis video games named for them, and the Virtua Tennis and Top Spin series of games feature dozens more real-world professional tennis players as playable characters.

The controllers used to maneuver players have advanced significantly since the initial potentiometer knobs used for Tennis for Two and Pong. One of the most notable advancements came with Nintendo’s Wii Sports, bundled with the launch of its Wii console in 2006. The functionality of the Wii’s innovative motion-responsive controller, the Wiimote, was demonstrated particularly well by the clear connection between the swing of a player’s physical controller and the corresponding swing of their avatar’s digital racquet. This incredibly close connection between controller-based motions and the real physical motion being simulated proved to be an especially compelling experience for players. Wii Sports has sold over 82 million copies (and is currently the third-best-selling video game of all time). More recently, tennis continues to be a subject for new technology in video games, with titles like VR Ping Pong (2017) for Sony’s virtual-reality console, the PlayStation VR.

Because the basic mechanics of tennis video games have been reimplemented so many times, over many decades, audiences have developed a strong set of expectations, skills, and knowledge of the genre. This creates an exceptionally robust space for designers to experiment in, by adding and juxtaposing unexpected mechanics and contexts. With Painstation (2001), media artists Volker Morawe and Tilman Reiff built a Pong-inspired arcade cabinet that paired surprising (and motivating) tactile punishment mechanics (including heat and mild electric shock), activated when a player missed the ball. With PONGS (2012), designer Pippin Barr iterated the idea of duplication and cloning in video game design with 36 variants of Pong, incorporating lasers, an invisible ball, falling Tetris blocks, and periodic world-geography quizzes. Each of these experiments worked because they built on players’ preexisting expectations and gameplay knowledge of the ubiquitous look, feel, and mechanics of Pong.

Perhaps my favorite tennis video game (and experiment within the genre), though, is one I first played long before I considered adding it to an archive. World Court Tennis (initially released in Japan in 1988 as Pro Tennis: World Court) was released in the U.S. for the TurboGrafx-16 in 1989. It featured a strangely incongruous mash-up of tennis video game mechanics with a role-playing fantasy game. Players in the game travel around Tennis Kingdom trying to win back the tournament prize money from the Evil Tennis King to help the Good Tennis King. Along the way they could explore castles; wander through fields, forests, and oceans; and challenge random tennis opponents, using prizes won from matches to purchase a new racquet or uniform. The tennis component of the game was fairly standard, but the absurd context of a role-playing fantasy game made the interaction and experience particularly unique and memorable.

Each new tennis video game (and its corresponding entry in the tennnis.org archive) builds on the varied scope of the genre while reinforcing the persistent core mechanic of two lines and a dot. I look forward to seeing how the genre responds to new hardware, graphics, and controllers, but I’m also excited to watch for the unexpected mashups and experiments that can challenge the genre and its mechanics. I’m eager to search for the right ingredient in a tennis cooking game, explore stealth tennis espionage mechanics, and dance to the tennis rhythm games of the future.

Tim Szetela is a designer, animator, and digital artist who visualizes structures of data and technology. He currently teaches at Princeton University and the School of Visual Arts. His game Rewordable was recently published by Penguin Random House.

Tennnis.org is an online archive of data and images detailing video games based on tennis and other racquet sports, from 1958 to the present. It was initially developed in 2015 by designer Tim Szetela and continues to be updated and expanded.

Featured in Racquet Issue No. 5