String Theory, the Library of America’s brief anthology of David Foster Wallace’s tennis writing, shouts “gift” when you pick it up. It is easy to hold, both pleasantly hard and light. The cover is rendered mostly in the wet green of a tennis court, the “o” of Theory printed in the “optic yellow” introduced in 1972 to help people track a tennis ball while watching on television. The rest of the type is white, and all of it is embossed onto the front board, a design that suggests the frugality of the patrician. By dispensing with a common element—a dust jacket, the unnecessary team member—the object becomes quietly informative, authoritative by virtue of choosing to be minimal. One of the main attributes of the patrician aesthetic is to mask effort, to erase the body. But sports are themselves because of a body, and athleticism has its own language. You can’t flatten a sport.

These five Wallace essays are common to syllabi and easily found in other collections, so they won’t surprise anyone who already knows his writing. As an introduction to Wallace, though, the book works. We get memoir, philosophy, reporting, and a good dose of Wallace’s writerly risks in the course of 138 pages. Tennis is an organic, not stupid principle for framing Wallace. He played the game from childhood on, thought about it obsessively, and returned to it often as both subject and practice. We don’t need to buy the “greatest tennis writer ever” line to appreciate how good Wallace is on tennis (and how, maybe surprisingly, it triggered some of his most controlled writing).

The book opens with an introduction by John Jeremiah Sullivan that addresses the origin of the word “tennis.” Most sports do not need this kind of explanation—you do not wonder where someone got the name “basketball.” But a casual fan, like me, did not know that “tennis” began as a French word—“Tenez,” or “Take it”—shouted before each serve. As Sullivan describes it, the “Neapolitan ear” took up this term and by the time it drifted from Italy into England, and Shakespeare, the word had become “tennise,” or simply “tennis.”

The introduction eventually flirts with a distortion of category. Sullivan isn’t a real opponent here, or even a straw man, as he’s too careful to call tennis “the literary sport.” He writes, instead:

It is perhaps not far-fetched to imagine Wallace’s noticing early on that tennis is a good sport for literary types and purposes. It draws the obsessive and brooding. It is perhaps the most isolating of games. Even boxers have a corner, but in professional tennis it is a rules violation for your coach to communicate with you beyond polite encouragement, and spectators are asked to keep silent while you play. Your opponent is far away, or, if near, is indifferently hostile. It may be as close as we come to physical chess, or a kind of chess in which the mind and body are at one in attacking essentially mathematical problems. So, a good game not just for writers but for philosophers, too. The perfect game for Wallace.

Sullivan seems to know the dangers at hand. “Physical chess” acknowledges that we can’t call chess a sport, though it is a game.

Writing demands a form of controlled daydreaming, an act based in losses of self that alternate with conscious assertions of self—the edit, the second draft, the rewrite, an act opposed to the nature of all games and sports.

The end of this paragraph, though, goes ahead and re-shelves tennis anyway, moving it from “sport” to “game.” This threatens to remove the athlete from the act, which segues right into denying athleticism its own logic and its own poetics.

Backing up for a moment, though. Tennis is “the most isolating of games”? In my ten or twelve attempts to get through a game of tennis—or a set—I have felt not isolated, but very easily seen. Given the chance to score one ferocious and elegant point if I also agreed to a swift, equally elegant death, I would have taken it. The most isolating experience I’ve ever had in sport is playing left field in a baseball game that involves no strong hitters. You can think about eternity, perhaps even design the upper- left corner of a crossword puzzle. Even if you drift off, the crack of a well-hit ball and a few shouts are usually enough to prompt you back into position.

But the larger problem, one that can dog any subject, tennis or otherwise, is the “x is the literary y” problem. Chess recalls some aspects of writing, but Sullivan had to put spin on “chess” with the word “physical” to bring it back closer to sports, a move that suggests the dangers of attempting the comparison at all. Chess involves thinking, guessing, and lots of invisible effort, bringing it close to writing but not close enough. Chess has one desired end; writing does not. Writing demands a form of controlled daydreaming, an act based in losses of self that alternate with conscious assertions of self—the edit, the second draft, the rewrite, an act opposed to the nature of all games and sports. (The video review is the closest sports get to a rewrite, but often supports already arbitrary decisions by referees who aren’t writing the sport to begin with. No really good editor would want to be compared to a video review.) The athletic act brings an advance, a retreat, or a void, and then leads to the next act. If sport is writing, it is improvised, within rough guidelines that bend in the face of your opponent and her guidelines. You don’t have to bat away someone else’s hands when you type; not very sporting, writing. Literary, though.

If we focus on the process, the hollowness of a “literary sport” as a trope is clear. Athletes, even bad ones, arrange their minds to help their bodies track an element: the ball, for example. Though the muscles and synapses are doing subtle trade, the bits of the brain dedicated to written and spoken language go largely quiet. This necessary bit of rerouting is what makes playing sports both thrilling and relaxing. As the internet says, you have one job. Where is the ball?

As a teenage first baseman, I was likely to be fielding slow grounders in every single inning, unlike our theoretical outfielder. I was going to be as busy as baseball gets, after the pitcher and catcher. My available powers had no job beyond tracking the position of the ball and where my body was in relationship to it. This is the core act of any sport, whether you’re a passable athlete thinking in horizontal planes (young me) or one of those three-dimensional visionaries who finger time and space (Serena, LeBron, Steph).

So why even get close to the trap of the “literary sport”? This is a challenge for writers, not athletes. We want to characterize something for those who don’t know the thing, and similes using two known quantities are quickly and easily seen. (The optic yellow of rhetoric.) In 1984, if you had written that a shell-toe Adidas three-stripe was “the rap sneaker,” you wouldn’t have been far from the truth. Run-DMC made the shoe part of their uniform and cut a deal with Adidas after cutting a song about the shoe. By the ’90s, though, the sneaker was no longer seen, and the Timberland boot had begun to signify allegiance to the sister nations of hip-hop and R&B. Decades later, the shell-toe Adidas says “retro hip-hop,” but Timberland boots are probably just boots. Even when they work, broad-stroke similes often have a short shelf life.

“Tennis as literary sport” isn’t entirely flawed, conceptually, since it hints at its own roots in the royal court: the ultimate patrician lineage. But that was then, to put it mildly. Of late, tennis has been dominated by two sisters, one of them possibly the most dominant player of all time. This would be problematic for royal ghosts, though Wallace would likely have taken on the political implications of the Williams sisters’ reign. In 1995 he wrote “Democracy and Commerce at the U.S. Open,” which dealt largely with corporate ad placement (a thing that could still surprise and offend). In 2016, given the same title, how could he not take on the spectacle of an athlete of Serena Williams’ caliber being compared to a horse by a major newspaper?

As much as I’d like to read him on Serena’s run and a world in which she has to reassert her dominance as often as people grant it, I am more excited to read the next great tennis writer. That writer, like Wallace, only needs the sport to be itself, and will see lines that were obscured, subtle arcs, and the minor, unexpected adjustments that create major results.

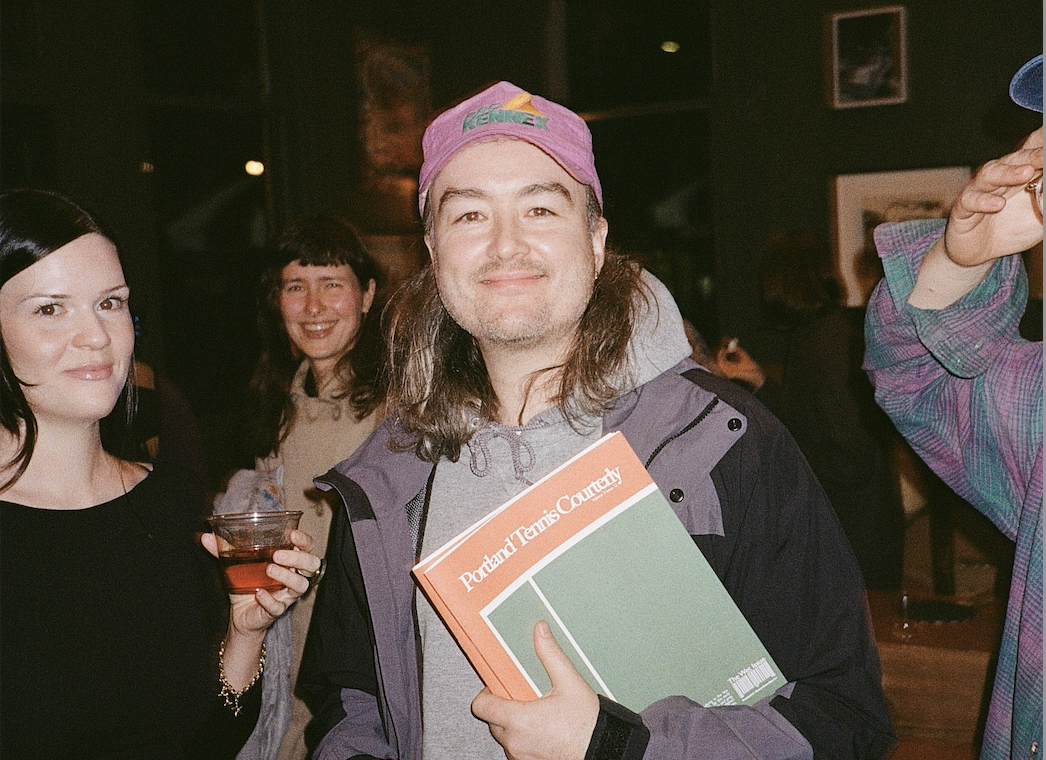

Featured in Issue No. 1

Sasha Frere- Jones is a musician and writer from Brooklyn. He lives in Los Angeles. After Sports Illustrated honored Williams with its once- prestigious award, the Los Angeles Times, in a tweet, asked, “Serena Williams or American Pharoah: Who’s the real sportsperson of 2015?” The response to the comparison was near-universal outrage.