Aussie

Aussie

Aussie

Oi,

Oi,

Oi.

By Joel Drucker

Illustration by Sergio Membrillas

Wimbledon, 1968. The No. 1 tennis player in the world, Rod Laver, had hurt his left wrist, the small but significant hinge that allowed him to make all those last-minute adjustments with his Dunlop Maxply for volleys, passing shots, serves, and all else that made him a genius like none other. The wrist would need to be taped.

There was only one logical place to perform this procedure. Making their way discreetly through the streets of London, Laver and his wife, Mary, jointly squeezed into a telephone booth and wrapped the injured wrist. This way, no one would know.

There was tennis to be played. As for injuries, principle No. 1 of the Australian code, expressed by Laver’s rival, lifelong mate, and winner of a men’s record 28 Grand Slam singles and doubles titles, Roy Emerson: “If you’re hurt, don’t play. But if you play, you’re not hurt. There are no excuses.” Of those who cite injuries frequently, the Aussies will say, “I have never played him when he was well,” a veiled form of contempt. No stories, please. Talk is cheap. Action is all, drama often articulated by Aussies this way: “Got through it.”

Of the four hosts of tennis’ majors— among them, the haughty French, taciturn Brits, and besieged New Yorkers—none are friendlier than the Australians. Defending men’s champion Roger Federer has dubbed the Australian Open “The Happy Slam.” Perhaps this country’s roots as a British penal colony have long placed an emphasis on loyalty and community. Or is it that geography and weather—a massive, sun-drenched island removed from the world’s trouble spots— make Australians so affable?

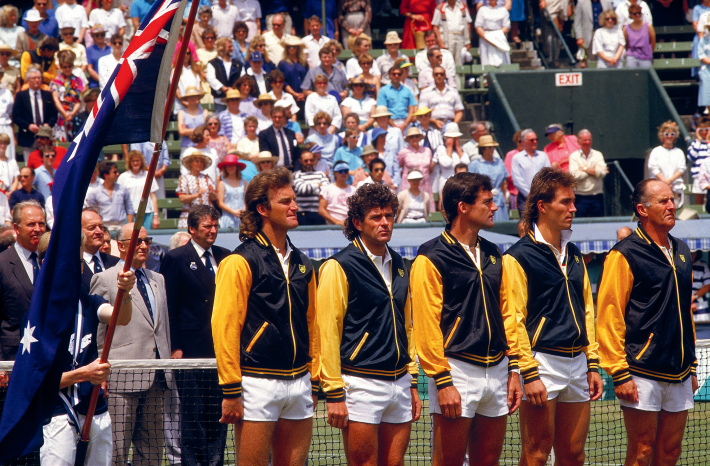

But the Aussies take their sports very seriously. Sportsmanship, reticence, and camaraderie are the cornerstones of the Australian code. Aussies are tennis’ version of the Mercury Seven astronauts, subdued warriors graced with the right stuff, who for decades have treated tennis like a team sport. Hearty fellowship is one reason Australians are so often among the best doubles players. It’s also why Davis Cup has long been a way for Australia to assert itself on the world stage. Call it a counterattack on Australia’s onetime ruler, Great Britain, once its captor nation and also the country that invented tennis. To an Aussie, nothing matters more than those moments when his mates are counting on him.

“Sweden, 1964, the opening match of Davis Cup,” goes a tale frequently told by Emerson. “I was up against Jan-Erik Lundquist, a man with very good passing shots. Thick clay, heavy Tretorn balls. Lundquist won the first two sets. I won the next two. He was up 5–2 in the fifth. It wasn’t looking so good.”

Mission Control for the Australians for 30 years was Harry Hopman. A fine player in his own right, Hopman became Davis Cup captain in 1938, a post that made him dictator of Australian tennis for three decades. It was Hopman who determined which youngsters could leave their homeland and compete around the world. It was Hopman who ran the practices like a martinet, be it having his boys take a long run through London, play five practice sets, or ceaselessly refine volleys and returns.

It was Hopman who sat on the bench throughout those Davis Cup ties, whether it was a sweltering day in Mexico City, a cold afternoon in Cleveland, or, in this case, versus a seemingly untouchable Swede on the brink of victory. “You’ve got him now,” Hopman told Emerson.

What?

“Look at him. He’s doing push-ups. He’s all wound up. It’s over. He’s keen to lose. Now’s the time.”

Emerson: “So I picked it up a bit and won the next five games.”

Picked it up a bit. Got through it. This is the Aussie way. It is the epic that resists excess. Bad luck. Well done. First to the net, first to the bar. “We drank at night to let it go,” said seven-time major singles champion John Newcombe. “Others would brood too much about their losses. We didn’t brood. We played.”

Perhaps there is also a cultural factor afoot. In America, even now, the tennis player is a peripheral athlete, forced to defend his athletic prowess versus baseball, football, and basketball. This has never been the case in Australia. Tennis Down Under has always been smack in the thick of the sporting culture, with Australian tennis players regarded as legitimate athletes rather than precious prodigies. It’s easy to imagine Newcombe as a pitcher, Patrick Rafter at halfback, Evonne Goolagong a hurdler, Rennae Stubbs a power forward, Ashleigh Barty and Lleyton Hewitt at point guard. Treat a person like an athlete and they will conduct themselves like one.

The Golden Era of 1950–75, when Australians dominated the majors and won the Davis Cup 16 times, has long passed. Other nations such as Sweden and Spain followed the Aussie principles of hard work and camaraderie to become significant tennis powers.

Eastern Europeans, hungry for freedom and financial goodies, blossomed and now pervade.

In Australia, Open tennis left players more accountable to the marketplace than to a single leader like Hopman or even to one another. Mark Philip

poussis and Hewitt each fought hard to earn Davis Cup victories, but neither was squeaky-clean. Philippoussis, fueled by a maniacal father, intermittently squabbled with his mates, most notably in 1998 when he announced the end of his Davis Cup career because he felt team leaders Newcombe and Tony Roche had failed to support him enough when his father battled cancer. In time, all kissed and made up, Philippoussis being the closer for a pair of Aussie team triumphs in ’99 and ’03. As for Hewitt, scattered controversies surfaced throughout his career, ranging from a potentially racially tinged match versus James Blake at the 2001 US Open to a lawsuit versus the ATP to a 2005 Davis Cup verbal tango versus Argentine Guillermo Coria that saw Hewitt accuse his opponent of spitting at officials.

If Philippoussis and Hewitt revealed cracks in the code, Bernard Tomic and Nick Kyrgios have pretty much blown it to pieces. Tomic has frequently tanked, has overtly reveled in his lack of effort, and by now is likely a lost cause. Kyrgios, two and a half years younger than Tomic, is far more of a conundrum. An admitted basketball zealot, Kyrgios loves team events, and it appears that he’s on his way to becoming a Davis Cup stalwart. But his week-to-week dedication— the mental, physical, and emotional fitness and composure that Hopman drilled into his charges—is often suspect.

The likes of Laver, Emerson, Newcombe, Rafter, and Ken Rosewall are too nice to overtly say it, but surely they wince upon seeing Tomic and Kyrgios disgrace the game and even the entire nation. “Well done” are two words in the Aussie lexicon that constitute high praise. Sadly, two other words from that Down Under dictionary have applied to this duo: “pitiful effort.”

The female Aussies have also left a mark, often with forceful, all-court tennis (extremely short book: “Bad Australian Volleyers”). Margaret Court is a paradox, a great champion who took fitness and athleticism to new heights and social consciousness to new depths with her horrific, homophobic comments. Far easier to digest the silky-smooth elegance of Evonne Goolagong, winner of seven Grand Slam singles titles between 1971 and ’80, who is also one of the most popular players of all time.

Aussies are tennis’ version of the Mercury Seven astronauts, subdued warriors graced with the right stuff, who for decades have treated tennis like a team sport.

Joining those two in the International Tennis Hall of Fame is Lesley Turner Bowrey, a two-time Roland Garros singles champion who married a fine Aussie player named Bill Bowrey (winner of the last Grand Slam event played before the start of Open tennis, the ’68 Australian Championships).

More recently, there has been the resurgence of Ashleigh Barty, a feisty net-rusher who quit tennis in 2014 to play cricket—but in time returned to tennis, soaring up the ranks in 2017 from 325 at the start of the year to 23 by early autumn. Right alongside Barty is a Russian transplant, Daria Gavrilova, a versatile tactician still seeking to discard intermittent negativity for the purely positive. Then there’s the accomplished doubles player Casey Dellacqua, a nimble lefty who, sadly, has often made fewer headlines with her tennis and more due to Court’s attacks on her openly gay relationship. It’s uncertain, though, if any of these Australian women will fare as well as Samantha Stosur, who beat Serena Williams to win the 2011 US Open singles title—but has never since been to another Slam final, the result perhaps of a certain level of mental and technical sloppiness. And so, if nowhere as pervasive among the elite as they once were, Aussies continue to strongly flavor the culture of tennis. Australian values shaped the development of Pete Sampras, who cited Laver and Rosewall as the inspirations for his playing style and demeanor. The land Down Under heavily shaped Roger Federer, coached in his formative years by Aussie Peter Carter. Tennis teems with Australian coaches, hitting partners, commentators, players, and, more recently, a homeland Grand Slam that in recent years has at last come into its own.

The significance and excellence of the Australian Open is a recent occurrence. For decades, everything from distance to facilities to timing made the tournament by far the least important of the majors, its fields significantly shallow. The ’68 Aussie won by Bill Bowrey didn’t feature a single top tenner. Over the next two decades, it seemed headed toward irrelevance (believe it or not, in the boom years of the ’70s and ’80s, among the men an indoor tournament in Philadelphia was a far more cherished title). But in 1988 a new facility opened, first called Flinders Park, now named Melbourne Park. With a venue on a par with all the other majors and such innovations as roofs (three at Melbourne Park), the Australian Open has at last created its own identity—a grand kickoff to the tennis year, all players healthy and hopeful that the coming season will surely be their best.

The Aussie flame also burns brightly one week a year at “Tennis Fantasies with John Newcombe and the Legends,” tennis’ longest-running tennis fantasy camp. Held each October at Newcombe’s ranch near San Antonio, this event stars such vintage Aussies as Newcombe, Laver, Emerson, Fred Stolle, Owen Davidson, and the more recent player Mark Woodforde (all inductees in the International Tennis Hall of Fame), as well as their mate Ross Case and a troupe of prominent American ex-pros, including Hall of Famer Charlie Pasarell, Marty Riessen, Brian Gottfried, Dick Stockton, Rick Leach, and the Jensen brothers. Under the eyes of these greats, 100 men (there’s a mixed event in March) spew blarney, bash beer, share war stories, compete on teams led by the legends, and form friendships that in many ways mimic the fellowship the Australians cultivated at home and around the world.

This past fall marked the camp’s 30th edition. Though by now I’ve attended this event 21 times, it remains daunting (and delightful) to sit down on a changeover and see Rod Laver coaching your opponent. Then again, I’ve often benefited from Newcombe’s courtside counsel. “Try different things,” he once told me, “and then, when you find the one that works, have the faith and courage to stay with it.” Faith and courage: the theological warrior. Pick it up a bit.

Over 30 years, a remarkably inclusive community has emerged. “I don’t care how well you strike the ball,” said Emerson. “I care how much you try.” There are comebacks and there are chokes, but, as Stolle notes, “each day, exactly half the campers win and half the campers lose. We’re all in this together. That’s what we Aussies did. We looked out for each other. Different than you Yanks.”

When the matches are over, the Aussies are keen to listen—briefly.

Emerson: “What happened today, blue?” “I lost the first set 6–4 and was up 4–2 in the second, but lost it 7–5.”

“It looked like you weren’t taking care of your overheads as well as you usually do.”

“He’s a pretty good lobber.”

“Yes, he is.”

Then comes a pause. Stop. Rod Laver hardly talks about his losses. Why should you? Better yet that you get out there with one of your mates and hit 25 overheads first thing tomorrow morning.

One afternoon at Tennis Fantasies, a player coached by Newcombe blew a big lead and lost the match on a bad volley error. As the disconsolate man sat with a towel over his head, Newcombe knew what to say. “At Forest Hills in ’69, I was in the semis versus Rochey, serving in the fifth set at 6–all, deuce. I threw in two straight double faults. And then he served it out. Just like that. Guess we both know what it’s like to see one go like that, eh?” For that one moment, it didn’t matter if the spot was the US Open or Court 7 at a Texas ranch. This was the eternal Aussie genius: the democracy of effort. Everyone’s a player.

Joel Drucker writes for Tennis Channel and is a historian-atlarge for the International Tennis Hall of Fame. His most recent book is Don’t Bet on It.

Featured in Racquet Issue No. 5