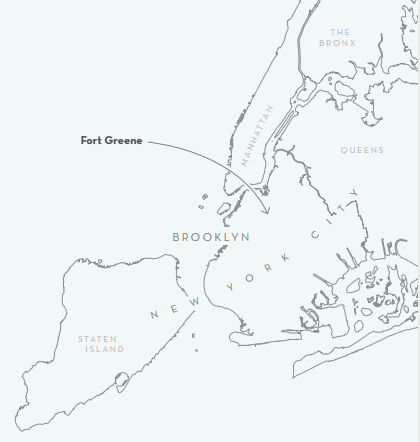

Technically, it wasn’t a castle castle. It was a 5,000-square-foot neo-Georgian building in the Fort Greene section of Brooklyn, built in 1927, that once housed the New York and Brooklyn Casket Company and later housed the South Oxford Tennis Club, for a while the only African-American-owned tennis club in New York City.

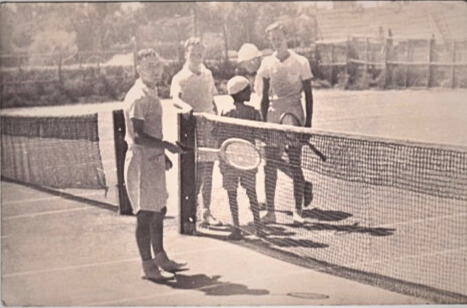

The club was at once stately, refined, rowdy, and way more down-to-earth than all that. What started out as a Brooklyn hot spot for matches on green Har-Tru clay would become, during its 16-year existence, a focal point for the surrounding, predominantly black neighborhoods. It was a place where kids could take free lessons, members competed in tournaments, future hip-hop legends spit rhymes, folks marked important occasions, politicians held fund-raisers, and the area’s gay community found an unlikely locus.

The man at the center of it all was Richard Northern, a tennis fanatic with an entrepreneur’s soul, who spent a good chunk of his life keeping his dream alive.

The man at the center of it all was Richard Northern, a tennis fanatic with an entrepreneur’s soul, who spent a good chunk of his life keeping his dream alive.

“Richard’s ambition was to transform this old space into something majestic, but it felt like it was being assembled in the moment with a dream of what it could be,” said Lynn Nottage, who won the Pulitzer Prize for Drama this year for Sweat and worked at the club as a receptionist one summer. “It was the beginning of Fort Greene gentrification, so there was an influx of new wealth. The club was aspirational, a place for affluent African-Americans to socialize and play tennis. All of us who worked there were local. It was exciting to have this glitzy place in Brooklyn and thrilling to be a part of it,” she said.

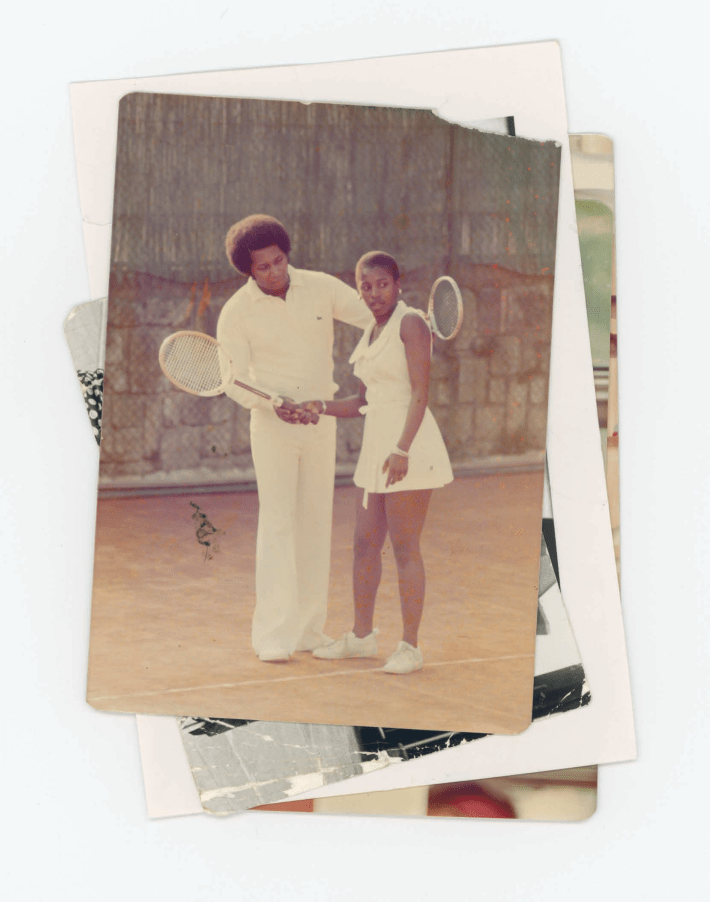

Raised in Washington Heights and the Bronx, Northern started playing tennis at 14. In his prime he was the definition of funky, complete with impeccable Afro and bell-bottoms, even on court. He spent summers playing at the Harlem public park nicknamed “The Jungle” and winters at the Harlem Armory under the tutelage of Sydney Llewellyn, who coached, and later married, Althea Gibson. Northern joined the American Tennis Association, the African-American organization originally formed in 1916 to counter court segregation, and played in tournaments throughout the Northeast. Eventually, he was hired to be the tennis pro at the Lawrence Golf Club on Long Island. Northern says that not only were there no black members, there were no other black pros on Long Island. He believes he was the first.

“I realized at that time that while I was an okay player, I was a great teacher,” said Northern, who now carries a distinguished professorial air but still seems and looks younger than his 76 years. “I went back into New York City to give lessons and it became my life for more than 30 years.”

Initially, Northern worked out of a facility near the United Nations, where his clients included photojournalist–cum–Shaft director Gordon Parks and Maurice White, the leader of Earth, Wind & Fire. Northern said the guy who ran the joint was a bigot—black employees were often fired while on vacation—so he built a single court in Midtown, brought along his clientele, and he was in business. At night, Northern was renting out his space to Tony Scolnick, a longtime NYC tennis impresario. They went into business together, renting out a burned-out methadone clinic to open the first-name mash-up RickTone Target Tennis. Northern thinks it was the first city facility to have automatic ball retrieval. When players hit balls over the net, they’d roll into a trough and pop back up to keep the tennis cage hitting session going without interruption.

In the process, Northern became a minor New York celebrity. In April 1976, he was one of the cover models for the New York Times Magazine menswear summer special. The accompanying profile breathlessly described his role as a “tennis advisor” for Air France, taking groups to glamour locales like Monte Carlo and the Caribbean. It featured a shot of Northern modeling a cotton jersey pullover by Jimmy Connors for Robert Bruce ($13 at Macy’s).

That same year, Northern was asked to host a public-access cable television program. He would star in roughly a dozen episodes of Richard Northern’s Tennis Hotline. It was a grainy black-and-white call-in show where Northern offered advice. In the one episode on YouTube, he addresses service stance, court positioning, and the proper backhand swing.

It also has a “Tennis Whiz Quiz” trivia game sponsored by local store Tennis Lady. And there were two guests. First up, a research physicist who invented an ingenious device to practice hitting a tennis ball inside a fully furnished living room. Hung from the ceiling, it counted every pure stroke and was designed specifically for apartment dwellers. The big get, however, was 33-year-old Arthur Ashe.

Taped in Ashe’s groovy pad, he and Northern discuss playing together as teenagers, and how individual grip techniques are as idiosyncratic as a person’s handwriting. And they take a look at Arthur’s art collection, which includes a statue of two naked figures—one black, one white—facing each other and eating a piece of fruit from both ends.

“Arthur was such a beautiful man, a wonderful, generous, smart guy, and I was honored to call him a friend,” Northern said.

Eventually, Northern found the former coffin dealer’s building in Fort Greene, where he’d moved in 1976. The manse on South Oxford Street sat on a block of abandoned brownstones. In 1981, he signed a $500 month-to-month lease with the City of New York. Serving as his own general contractor, Northern got to work rehabbing the place, adding new plaster, plumbing, doors, a brilliant checkerboard floor in the lobby, and a terrace overlooking the green clay courts. For the main lobby, he commissioned a large mural of faceless multihued tennis players in their dress whites. For a time, Northern lived on the top floor.

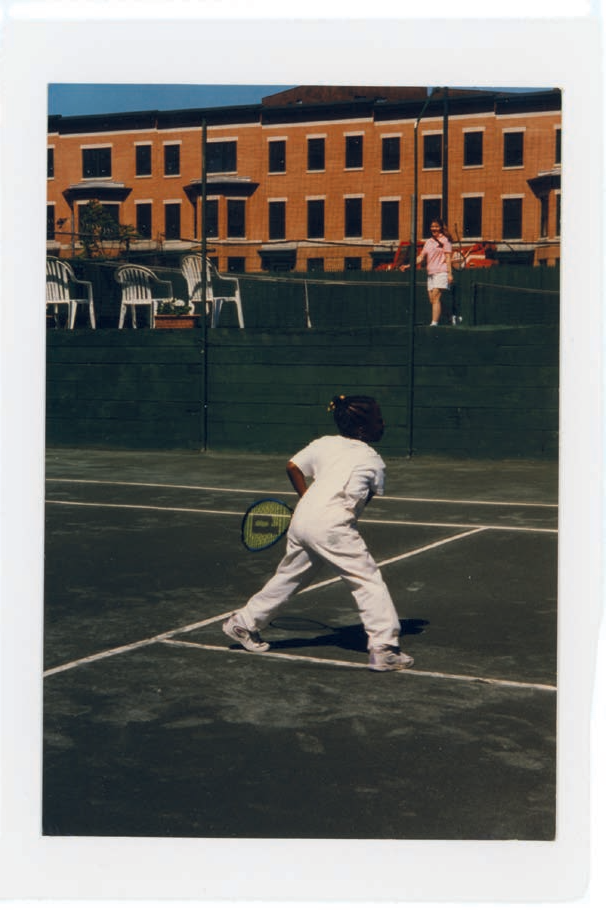

Over the first dozen years of the South Oxford Tennis Club, Northern spent $400,000 building tennis courts and restoring the once grand building where so many Brooklynites were previously prepped for the great beyond. Mel Swanson, who co-ran the free Junior Tennis Clinic, wasn’t always sure they were alone. “I swear, in some of those rooms you could feel the coldness, like ghosts were still around,” he said.

Ann Northern, Richard’s wife, worked as the club’s bookkeeper. “I saw the potential for South Oxford when we held one of our earliest events for Essence magazine,” she said. “I think it was called ‘Artists Who Cook,’ and all these creative people brought food from home that was served while their art was on display.”

South Oxford offered a nice surface contrast for the large tennis contingency already playing the hardcourts in nearby Fort Greene Park, and by the end, membership was evenly split between blacks and whites. In 1986, Northern added a second set of clay courts.

“Fort Greene and Clinton Hill were never desolate, they were always fairly nice neighborhoods. But these were the days of the drug wars, so nobody ever came to Brooklyn,” said Frank Gooden, a former member. “The club was an oasis. You’d show up to play at 10 in the morning, hang out, eat Richard’s food, split a six-pack while watching matches.”

Tennis got the club up and running, but Northern added a billiards room and a cigar bar so that club members could hang around after their game. Eventually, there were yoga classes, dance performances, and philanthropic fund-raisers. The club received city-council citations and community-service awards, Spike Lee used it for casting calls, and it even hosted an event for the prime minister of Jamaica. And as the hours grew later, it often transformed into one of Brooklyn’s hottest gay clubs.

“I ran the bimonthly U-Men U-Sweat parties out of the club for a half-dozen years,” said James Saunders, who founded Black Pride NYC in 1997. “We had a mixed crowd, gays and lesbians, but almost entirely black. It was an underground scene—usually people didn’t run through the door until midnight. We were mostly house-music heads, a little disco, some hip-hop later. It was come-asyou-are to dance.”

Celebrities found their way to South Oxford too. Politicos frequented the place, and in September 1992, senatorial candidate Rev. Al Sharpton used the club as his campaign’s headquarters on primary night. “His check bounced,” said Northern.

Unheralded rappers also popped in. The hip-hop writer dream hampton wrote about how she met Tupac Shakur in the early 1990s. She was a member of the Brooklyn chapter of the Malcolm X Grassroots Movement and asked Pac to help foot the promotional bill for a fund-raising concert for Mutulu Shakur. In the piece she notes, “Unsigned artist Biggie Smalls (this was before the name change) was headlining our show at the South Oxford Tennis Club, closing it out with his one hit ‘Party and Bullshit.’”

At another party, Mike Tyson decided to slap a random woman’s bottom. Her husband, a corrections officer, didn’t take kindly to Iron Mike’s shenanigans, but Tyson’s bodyguards took him outside and jacked the poor guy up, according to Northern. Northern added a billiards room and a cigar bar so that club members could hang around after their game. Eventually, there were yoga classes, dance performances, and philanthropic fund-raisers. The club received city-council citations and community-service awards, Spike Lee used it for casting calls, and it even hosted an event for the prime minister of Jamaica. And as the hours grew later, it often transformed into one of Brooklyn’s hottest gay clubs.

“I ran the bimonthly U-Men U-Sweat parties out of the club for a half-dozen years,” said James Saunders, who founded Black Pride NYC in 1997. “We had a mixed crowd, gays and lesbians, but almost entirely black. It was an underground scene—usually people didn’t run through the door until midnight. We were mostly house-music heads, a little disco, some hip-hop later. It was come-asyou-are to dance.”

Celebrities found their way to South Oxford too. Politicos frequented the place, and in September 1992, senatorial candidate Rev. Al Sharpton used the club as his campaign’s headquarters on primary night. “His check bounced,” said Northern.

Unheralded rappers also popped in. The hip-hop writer dream hampton wrote about how she met Tupac Shakur in the early 1990s. She was a member of the Brooklyn chapter of the Malcolm X Grassroots Movement and asked Pac to help foot the promotional bill for a fund-raising concert for Mutulu Shakur. In the piece she notes, “Unsigned artist Biggie Smalls (this was before the name change) was headlining our show at the South Oxford Tennis Club, closing it out with his one hit ‘Party and Bullshit.’”

At another party, Mike Tyson decided to slap a random woman’s bottom. Her husband, a corrections officer, didn’t take kindly to Iron Mike’s shenanigans, but Tyson’s bodyguards took him outside and jacked the poor guy up, according to Northern.

This is where the story of the club becomes a Brooklyn real estate story.

The core problem was that Northern never owned the club. He tried to buy it outright multiple times to no avail. Unlike most of Fort Greene, the block on which the club sat was never designated as a historic district, and in 1986 it was targeted for redevelopment. By August 1993, a 400-unit housing complex was in the planning stages.

Northern survived demolition orders and 11 eviction notices, all the while pleading his case that the tennis club was important to the community and should be folded into the housing plans. He spent years trying to get the building landmarked, which also went nowhere, and in December 1997, the South Oxford Tennis Club’s doors were shut for good.

“Richard owed me a favor, so I threw the last party,” said Saunders of Black Pride NYC. “It was right after Christmas, it was a blowout. I still miss the place. When it closed, it sent shock waves through the gay community.”

Four years later, it was demolished. By then, Northern had gotten into the more lucrative field of real estate speculation. After the club closed, he made little time for tennis. He played a little on vacation years back, but for all intents and purposes, his final sets were on his own clay courts.

“I played multiple times a week, some years every day, from the time I was 14 until I turned 55,” he said. “At that age, you don’t want to play on Fort Greene Park hardcourts when you’ve played Har-Tru.”

He’s never far from the game, though. Richard still watches tennis religiously, and on one April visit to his elegant Bedford-Stuyvesant home, he was intently monitoring a Nadal match from the Barcelona Open.

In the past few years, Fort Greene has become surrounded by massive housing structures, a host of new skyscrapers looking down upon the neighborhood’s quaint brownstone streets. One block that remains serene is where Richard Northern’s club once sat. “The one shame is that today, the tennis club would be booming,” Northern said. “There are so many more people in the area, especially families, and there is nothing like what we had going. The club was before its time. People came from all over to play there. I swear we had the best courts in New York City. Even better than Central Park.”

After everything is said and done in the name of urban renewal, though, no major development ever arose at the former address. In 2006, a nice little community park opened on the haunted and hallowed grounds. It’s got a hard court, not clay, but 20 years on, kids and adults are swinging racquets in basically the same spot where Richard Northern built a tennis castle.

Montana-bred, Brooklyn-based freelancer Patrick Sauer has written for VICE Sports, Smithsonian, Deadspin, GQ, and Esquire, among others. Lenny Dykstra still owes him money.

Featured in Racquet Issue No. 4