Gertrude “Gussy” Moran was a good player, not the best, but she was photogenic, with a handsome smile and a leggy gait. As she entered Wimbledon in 1949, the 25-year-old Californian was tired of her tennis shorts; she wanted a special dress for the occasion. So she did what many other women had done before her and wrote to Teddy Tinling— fashion designer to the tennis stars, couturier of the courts. In a 1988 interview with the Orlando Sentinel, Moran described the exchange, saying: “I wrote [Tinling] a letter prior to Wimbledon, asking him if he would design me something with one sleeve one color, the other sleeve another color and the shirt another color. He wrote back, ‘Have you lost your mind?’”

Wimbledon remains the world’s most prestigious tennis tournament, its formality somehow setting the tone for the game as a whole. No hooting and hollering. Dishes of strawberries and cream served for the spectators. And players must wear white. This “does not include off white or cream,” cautions the spectacularly strict Wimbledon

rule book. In the 1940s, the stakes were even higher. The year before Moran’s appearance at the tournament, Tinling had added a pink trim to the hem of a player’s skirt and been reprimanded by Wimbledon’s keepers for pushing the sartorial limits. Nonetheless, the designer sympathized with Moran’s desire to appear feminine. Tennis attire of the 1940s was defined by a unisex look. For female players, this meant lots of unflattering long skirts and shorts made of uncomfortable fabrics such as gabardine and wool. “They look like they’re made by grandmothers or sisters of grandmothers,” Tinling complained.

Never one to decline a challenge, he sewed a dainty white dress for Moran made of a soft-knit rayon that clung gently to her figure, with a shimmery satin trim. Moran loved it at the fitting, but had only ever worn shorts; days before the tournament, she asked Tinling to make a pair of matching panties to wear underneath. Aware that Moran had a “walk that had so much bounce she appeared to be treading on a succession of rubber balls,” and that her skirt would flutter prettily when she swung her racquet, he made her a set of underwear with a two-inch lace trim around the bottom. All he wanted, he later said, was to show off her mahogany-tanned legs.

How best to describe the uproar Moran’s lace panties caused? It was like the media reaction to Janet Jackson’s nipple slip at the Super Bowl, only infused with a sense of postwar puritanism. Every time Moran served, her skirt would fly up, and as she leaned forward, the white lace of the panties would proudly offset the tops of her bronzed thighs. Tinling wrote in his 1979 memoir Love and Faults that the moment was tantamount “to a star of today suddenly appearing topless on Wimbledon’s center court.” Every photographer was on his stomach on the grass, lens angled up, calling out to Moran to serve one more time. “Gussy was a very sexy girl who always played in very tight shorts,” Tinling told Sports Illustrated in 1969. “She was, like Lana Turner, a real sweater girl. The fellows used to crawl up the wall with delight when they saw her.” Moran made it only to the fourth round, but Tinling’s panties transformed her into a sex symbol. From that day on, the press nicknamed her “Gorgeous Gussy,” and she coasted on that fame for years.

The panties cast Tinling as a troublemaker, and he was banned from the Wimbledon clubhouse for nearly two decades as a result of the incident. It’s tempting to paint him as a subversive—upending authority, deliberately pushing Wimbledon’s stuffy, old-fashioned buttons. But in fact it was the tedium of tradition that Tinling felt truly allergic to. He called the all-white rule of Wimbledon “kitchen-sink tennis,” a reference to the color of porcelain, which he thought boring to look at. To him, fashion was a form of expression, and how could you express yourself without any color?

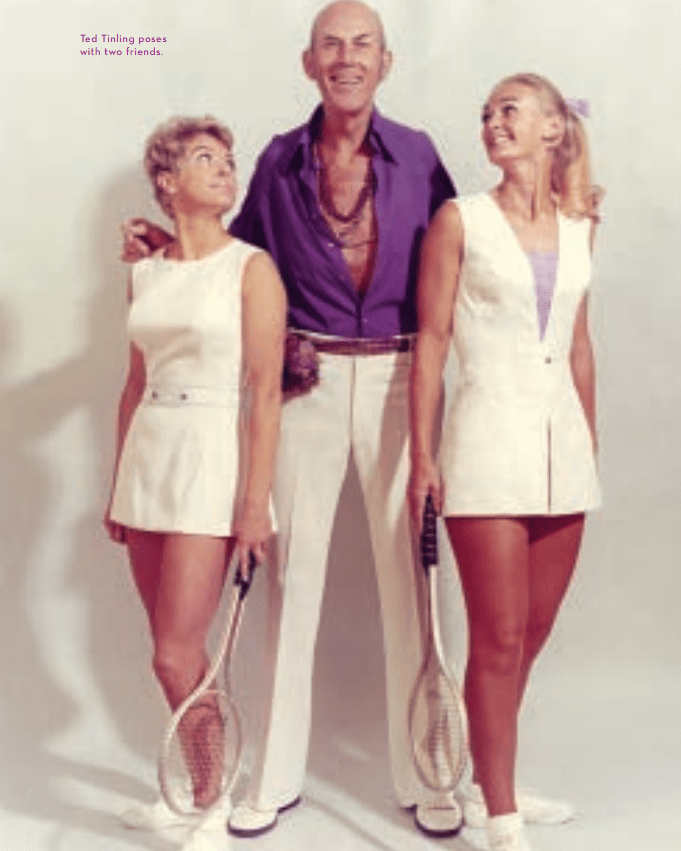

Tinling himself cut a natty figure in the world of tennis. A favorite nickname for him was the “Leaning Tower of Pizzazz.” Pictures show him to be completely bald, lanky, and very tall (he was anywhere from 6’5” to 6’8”, depending on who you asked and what kind of shoes he was wearing). He was fond of jewelry, bell-bottoms, and bright shirts that unbuttoned down to the navel. “Tinling was 59 years old on June 23,” read read the aforementioned 1969 SI profile, “but he dresses like a mod pop singer 40 years younger.” He was quick-witted and diplomatic, skilled in handling the egos of sports divas and stars, deft at parrying the complaints of his critics. And he had lived and breathed tennis for most of his life.

Born in 1910 in Eastbourne, England, Tinling’s childhood asthma prompted his family to move to the south of France, where he wound up a ball boy for one of the greats of women’s tennis: the balletic Suzanne Lenglen.1 He aspired to a career as a couturier, … but Tinling’s

panties transformed her into a sex symbol. From that day on, the press nicknamed

her “Gorgeous Gussy,” and she coasted on that fame for years.

and in the 1930s, his designs became popular with debutantes and wealthy Londoners. But wartime sanctions made production too difficult, and he eventually closed down his couture shop, which employed around 300 people. Tinling also played a decent game of tennis—he once entered the doubles draw at Wimbledon—and many of his clients put his understanding of how clothes should feel and move on the court down to his firsthand experience of the sport.

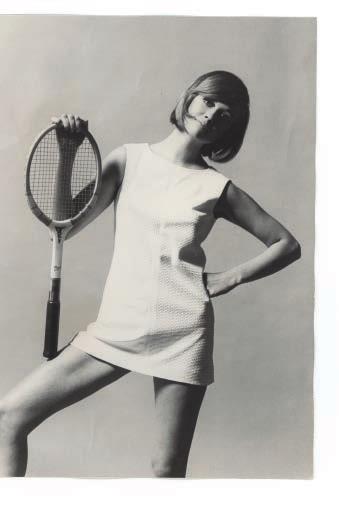

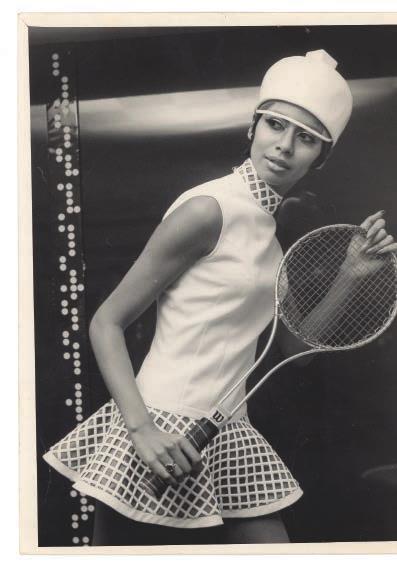

Looking back at his designs, it’s clear Tinling’s taste was always a little too obvious to be a great match for high fashion. He was fond of taking a motif—coconuts, say, for the beach—and repeating it across the front of a dress. He also knew how to be playful: On one dress from a leisurewear collection in the ’70s, footprints run around a garment’s bodice. He understood the harmony that impeccable style requires, but he lacked the sense of irony that great fashion designers often possess—how a suit can be transformed into eveningwear by removing

the white shirt, for example, or how an aristocrat’s riding pants can be turned into a kind of prototype boyfriend jean. Yet this sensibility made him perfectly suitable for tennis, where style is so in sync with form. And Tinling was a pioneer with material, eager to experiment with athletics-friendly fabrics like rayon and jersey.

As women’s tennis evolved, so did its politics, and Tinling is best remembered for his public support of some of the best female players in tennis history. The designer, who was openly gay his entire life, often spoke of his admiration for women, and his desire to celebrate their femininity.

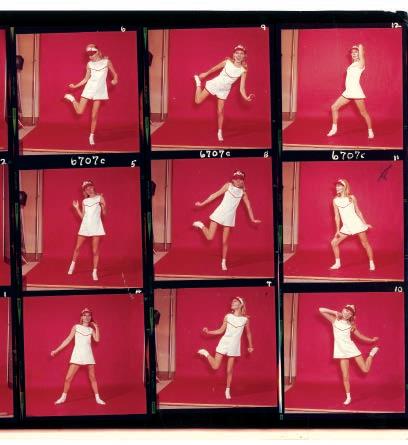

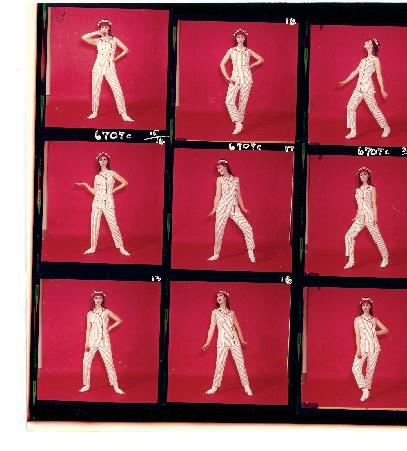

Images from Ted Tinling's lookbooks.

The designer, who was openly gay his entire life,

often spoke of his admiration for women, and his desire to celebrate

their femininity. And though he was old-fashioned, it seems

that, at heart, he believed women

could play tennis as

well as men.

And though he was old-fashioned, it seems that, at heart, he believed women could play tennis as well as men. In 1970, when Billie Jean King and a group of other top female tennis athletes (who together became known as the Original 9) organized with Virginia Slims to create their own tournaments, one where the women would earn as much prize money as men, they turned to Tinling to make their dresses.

“Ted was one of a kind and larger than life,” King recalled. “He wanted to know if I wanted the dress loose or tight; which way did I twist more when I played and a wide range of more functional things. But he also let me choose fabrics and sequins or mirrors and the special little touches that made a Ted dress a fashion creation. He made us all stars.” (Tinling also designed King’s dress for the Battle of the Sexes against Bobby Riggs in 1973.) Nancy Richey, another of the Original 9, said, “They were spectacular, his dresses. We were playing at night in arenas and it had a show-business atmosphere, with the way we were dressing with the rhinestone buttons and embellishments around the collar, sequins—you name it, he did it.”

Tinling loved beauty, and he loved the elegance and the spectacle of tennis. The designer passed away in 1990, just as sponsorship by athletic brands began to sweep through professional sports. Now the pros wear sweat-wicking outfits by Nike and Adidas, and earn millions doing it. But when you look at a Tinling dress hanging on a mannequin in the International Tennis Hall of Fame, you can still imagine the way it would shimmer in the sun as she— Gussie, Billie, Nancy—kicked up her leg for a serve, her skirt swirling with the spin of the ball.

There are a number of factors that contribute to the dominance of the white tennis uniform.

The dress code dates back to the Victorian era, when it was considered improper to be seen sweating. White linen was the most discreet of choices, being both light to wear and less prone to revealing unattractive armpit stains. The fact that tennis whites stained easily on the grass, making them harder to clean, along with the rise of the leisure industry, made the uniform all the more appealing to those who hoped to distinguish themselves from the working class. Tinling found the all-white dress code visually unstimulating, and when tennis began to be televised, he was quick to point out how often the camera panned to the sky or an awning to offer more color on screen. But Wimbledon’s recent tightening of its dress code in 2014—when it declared that there could be only “a single trim of color no wider than one centimeter” and broadened the all-white rule to include caps, headbands, bandannas, wristbands, shoes, and visible undergarments “that either are or can be visible during play

(including due to perspiration)”— is a reminder of how some traditions will never change. Even if the rules are considered draconian by many of the top players. “White, white, full-on white,” Roger Federer complained to The New York Times that year. “I think it’s very strict. My personal opinion: I think it’s too strict.”

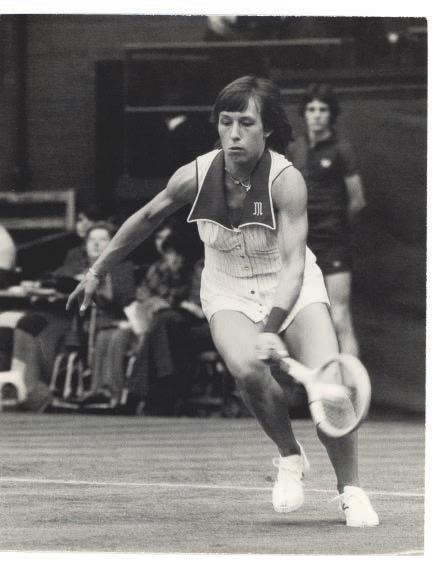

Ted Tinling made the monogrammed dress in which Martina Navratilova won her first Wimbledon singles title, in 1978. Its label reads, "Made With Love For The Champ.”

Thessaly La Force is a writer living in Brooklyn.

Featured in Racquet Issue No. 1