Illustration by Ping Zhu

I rooted for Pete Sampras, but I didn’t like him.

It was hard to warm to Pistol Pete over the course of his 13-year professional career. He lacked the charisma of his competitors—the wild flair of Agassi, the cheerful and handsome charm of Pat Rafter. Pete was dogged and hangdog. Pete was a brutish workhorse. Pete was boring, a merciless machine from which all personality (and pleasure, it seemed) had been scalpeled away. He was a willing and willful dinosaur, the last of the serve-and-volley greats.

Pete Sampras’ favorite band was, and probably still is, Pearl Jam. If Pete exhibited any emotion at all, it was an arrogant indignation when he lost and a sense of arrogant relief when he won. Pete played like winning was something the world owed him. But I still cheered him on, although he never inspired me.

Pete Sampras broke onto the world tennis scene in 1988, the same season that I became the No. 1-ranked 12-and-under female squash player in America, and the same year that I started paying attention to tennis. Squash was never on TV, and it wasn’t, and still isn’t, in the Olympics, which meant tennis was where I had to search for the closest reflection of myself—my small-potatoes goals and struggles amplified to the big time. Now, I’m not trying to compare myself to Pete here. (And if it came down to it, people will tell you that I was more of an Agassi type—volatile and flashy.) All I’m pointing out is that I took special notice of his pro debut because it happened the same year that rankings became important to me. I watched his ascent while I agonized about holding my spot atop the other 19 girls who qualified to be ranked in my division that year.

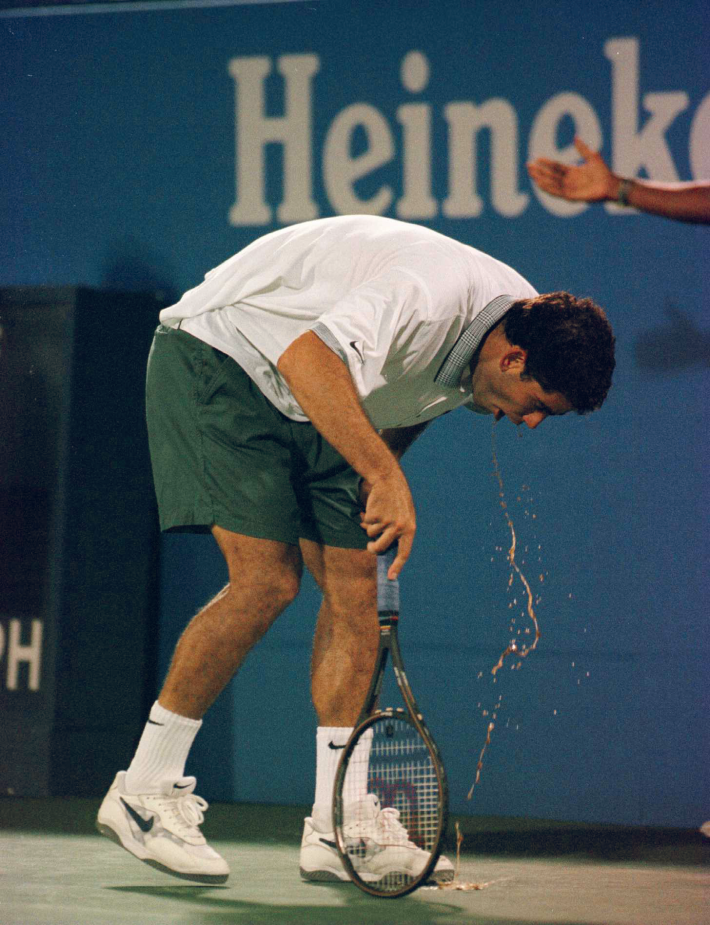

For someone who didn’t interest me that much, I can easily recall many highlights of Pete’s career: his first major title, the US Open in 1990; his terrible clay-court outing at the 1992 Olympics (Pete sucked on clay); his impressive run of hard-court Slam titles between 1993 and 1996. I remember Pete somehow eking out a win against Alex Corretja in the quarterfinals of the US Open in 1996, despite vomiting on court between points. I can instantly summon the image of his baggy, untucked collared shirts, the way his mouth hung slightly open as he served, a bead of sweat dangling on his lower lip. I remember the brutal one-two punch of his lethally clinical serve-and-volley game. I remember other things, too—that he voted Republican, that he dated the actress from Billy Madison, and that when he was younger his parents hired a separate coach for his forehand and backhand. This last fact was the one that convinced me that Pete was less human, more machine, a tennis robot painstakingly programmed.

In the 13 years I watched Pete, there were only two instances when Sampras demonstrated extreme emotion: the two times Pete cried on court. I’m not talking about those tears of sweet relief that many athletes shed after winning majors, but real, raw distress— the kind of ugly crying that makes you give someone a wide berth in public.

Pete Sampras broke onto the world tennis scene in 1988, the same season that I became the No. 1-ranked 12-and-under female squash player in America, and the same year that I started paying attention to tennis.

The first came during a quarterfinal battle with Jim Courier during the 1995 Australian Open when a spectator urged Sampras, who was down two sets to love, to win it for Tim Gullikson, Sampras’ coach, who was dying of brain cancer. Sampras, who was sitting in his chair, put a towel over his head and began to sob uncontrollably, then somehow got a hold of himself and took Courier out in the fifth. But even here there was something workmanlike to his distress. A voice cried out, telling Pete to win. So he did.

The second time—the one that really got me—was when Pete wept after losing to a 19-year-old Swiss kid with a heavy brow and nubby ponytail. (I’d seen this same kid play in a local tournament in the Netherlands the year before and wasn’t terribly impressed.) For the first time, I felt something for Sampras beyond a general hope that he would win. I felt both heartbreak as well as a strange sense of relief.

You see, Pete knew, and I’m not sure how he did, that his career was over. For a player who hadn’t been capable of raising my blood pressure over years of grueling five-setters, I suddenly felt despair. Pete was finished. Other players—Agassi, Seles, and Capriati—came and went and came back again. But Pete was done. I cannot think of another moment in all my years of watching professional tennis—no, not just tennis; professional sports, where there are few givens—that I have known something so clearly.

Pete retired a year later after winning a final major, and like a true dinosaur, he vanished. For more than a decade Sampras had dominated men’s tennis; he was men’s tennis. Then he was gone—he and his entire style of play made extinct. While most greats have a second act in the coach’s box or the broadcast booth, Pete’s absence stuck me as remarkable, eerie almost.

Watching Pete cry on Centre Court at the All England Club, I realized something: From that moment on, I would experience the retirement of all my heroes. Every sports career that inspired me would come to an end, mine included. I would witness beginnings, meteoric rises, and eventual declines—a life cycle reduced to a decade or more of competition, mortality played out on court and on the field.

I joined the women’s professional squash tour in 1998, right after graduating from college. I’d been the best junior, then the best collegiate player, in the country. But as a pro, I didn’t exactly set the world on fire. I had fun. I made ends meet. I won a few small tournaments. I was ranked 38th in the world, which you might consider impressive or not, depending on what you know and think about women’s pro squash. I consistently represented the United States at the world championships and Pan Am tournaments. My national ranking vacillated between 3 and 6.

I don’t have to tell you that squash, at least in America, isn’t a sport with a deep field. The majority of top college players cap their careers with their final collegiate match. A few go on to play pro, and most of those don’t stick around too long. I won’t say it was easy—I did have to train hard—but it was comfortable for me to hang around in the top five or so players in the country, a feat I felt I could manage for years to come. Years and years.

Squash was so much a part of me and my identity that it was impossible for me to imagine quitting. I couldn’t envision my life without the excitement (and the stress) of competition and the pleasure of traveling to do so. But I also knew that I wouldn’t, and couldn’t, play forever. My interests, from writing to staying up too late, were too far-ranging to sustain my professional squash ambitions. But how would it end? In injury? In the achievement of my one remaining squash goal—winning the U.S. National Championship? (I never did.)

In the end, it was neither of these. I hung on too long, past the moment when I still thrilled at checking my competition outfit in the mirror, music blasting in my ears as I shouldered my bag, as I prepared to walk onto court. I moved away from the sport incrementally, so slowly in fact that each tournament I foolishly entered damaged my overall enjoyment of the sport I loved, each match I struggled through overshadowing the ones that had previously inspired me. I didn’t so much quit as drift away from the competition—a slow, unsatisfying fade.

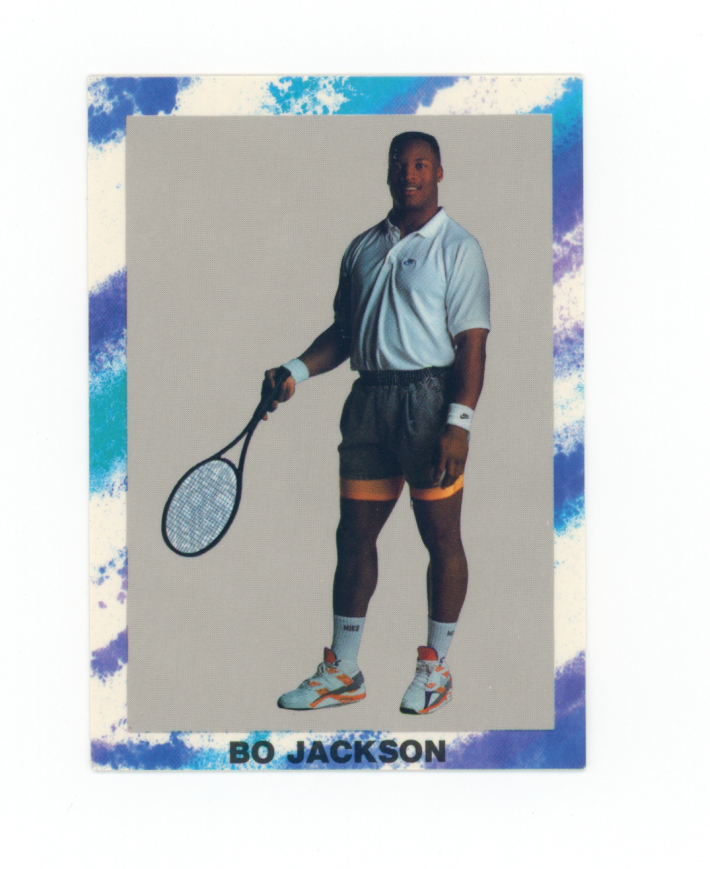

One morning in 1991, my flinty and strict ninth-grade history teacher, Jack McShane, sat down at his desk and with no preamble read A.E. Housman’s “To an Athlete Dying Young.” I was 13, an age when witnessing an adult visibly moved to tears made me extremely uncomfortable. The night before, Bo Jackson, one of the greatest athletes of all time, had suffered a debilitating hip injury that would end his football, and later his baseball, career.

I didn’t really follow Bo beyond the inescapable “Bo Knows” campaign. I didn’t understand Mr. McShane’s reaction, and I wouldn’t until I saw Pistol Pete crying after his defeat at the hands of Roger Federer.

Pete became human to me in the immediate aftermath of his loss to Fed. It wasn’t simply that the younger player had forced Sampras to confront his mortality, bringing him face-to-face with the twilight of his career in undeniable terms. Federer’s victory over the old champ revealed to me, and perhaps others who followed Pete in the way that I did, that there had been joy in Sampras’ game all along, and now the joy was gone. It was both a devastating revelation and one that revealed a surprising depth and awareness to a person I imagined lacked both.

Pete had a trick up his sleeve, a game face that surprised me. He’d skillfully hidden the joy that I had allowed myself to lose. And he’d decided not to squander it by continuing to play, but to cherish it and to protect it from those set on destroying it. Pete was on to something, something that I’ll leave Housman to articulate, something that the poet understood better than I, namely the tragic beauty in quitting. Like the deceased runner in Housman’s poem, Pete did not “swell the rout/Of lads that wore their honours out,/ Runners whom renown outran/And the name died before the man.” Pete didn’t wear his honors out; instead he walked away, honors intact, leaving us, especially those of us who never learned when to quit, in awe.

Ivy Pochoda is a former world-ranked squash player and the author of Visitation Street. Her most recent novel Wonder Valley was just published by Ecco/ HarperCollins.

Featured in Racquet Issue No. 5