A Wimbledon local looks back on three decades of queuing.

An Excerpt from Standing in Line by Ben Chatfield

I was born in Wimbledon and grew up down the road from the picturesque village that bears its name. We lived in a slightly less verdant area, but I am, effectively, a local. I first arrived at the top of Church Road, which descends from Wimbledon Village towards the All England Lawn Tennis and Croquet Club, with my mum, in June 1984, aged ten and a twelfth, staring openmouthed and captivated as that giant green world unfurled in front of me. Even now, whilst I live within an over-hit lob of Centre Court, I still sometimes get that feeling in my stomach.

Whether I arrive from Wimbledon station to the south, via the old Routemaster bus, or by legging it up Wimbledon Park after getting to Southfields tube station to the north, the incredible sense of excitement involved in arriving at the club’s grounds has never left me. It’s a feeling that says summer, tennis, glamour, and the whole world coming here, to my own doorstep in a quiet, almost suburban neighborhood that heaves with tennis-crazed people a fortnight each summer. It’s like a massive film set, or global reality TV show, based right where I live.

1. You are in the Queue if you join it at the end and remain in it until you have acquired a ticket at the turnstiles at Gate 3.

2. Your position in the Queue cannot be reserved by the placing of equipment— you must be present in person and hold a valid numbered and dated Queue Card. Queue Cards are issued one per indi- vidual and are strictly

nontrans- ferable.

3. You may not reserve a place in the Queue for somebody else, other than in their shortterm absence (e.g., toilet break, purchase of refresh- ments, etc.). Temporary absence from the Queue should not exceed 30 minutes.

standing in line/topfoto

5. There are no left- luggage facilities inside the Grounds; only one bag per person will be allowed into the Grounds and any item/bag exceeding

40cm x 30cm x 30cm (16" x 12" x12") in size or hard-sided bags of any size must be left in one of the facilities outside the Grounds (please note that bags deposited in left luggage should be no bigger than 60cm x 45cm x 25cm).

standing in line/topfoto

But it’s that queue—the Queue—that has been a source of fascination to me for more than 30 years. Like most people, I don’t really enjoy just standing in a line for hours on end, but for Wimbledon I don’t mind.

“Where other nationalities mass frenziedly, the British queue,” according to the 20th-century Hungarian-born British journalist George Mikes. “An Englishman,” he said, “even if he is alone, forms an orderly queue of one.”

The phenomenon is said to be linked back to the world wars and rationing, subconsciously seeking to make an emotional attachment with the community you lived in. Likely with a touch of hyperbole, Mikes goes on to say, “Queuing is the national passion of an otherwise dispassionate race. The English are rather shy about it, and deny that they adore it.”

As writer Ranjani Iyer Mohanty, an experienced and patient queuer, explained in The New York Times a few years ago, “In a 1969 paper…Harvard professor Leon Mann called queues a miniature social system. Richard Larson of M.I.T. took it further…. In order to function, he argued, a queue must be fair: It must follow the rule of FIFO—first-in, firstout. People must be served in the order they are lined up in; otherwise, the result might be queue rage. Queues also have a profound philosophical aspect. The logic of the line… is liberté, égalité, fraternité. It translates like this: We are free to run around like chickens with our heads cut off, but if we behave in a brotherly/sisterly/neighborly manner and queue up, we all have an equal chance of getting in.”

Or, as George Mikes put it, “a man in a queue is a fair man…the image of a true Briton.”

7. Do not leave bags or other items unattended at any time; they will be removed and may be destroyed by the Police.

8. Confiscation of a Queue Card constitutes refusal of entry to the Cham- pionships’ Grounds.

9. Anti-social behaviour likely to cause annoyance or offence to other queuers will not be tolerated. Specifically: Barbecues are NOT permitted in the Queue, in Wimbledon Park, in the Golf Course or on pavements outside the Park or Golf Course.

Overnight queuers should use tents, which accommodate a maximum of two persons.

Please do not bring or erect gazebos.

Do not play music or ball games etc. after 10 p.m. At this time all queuers must be close to their tents and settling down for the night, recognising that other queuers will be going to sleep. This rule is strictly enforced.

standing in line/topfoto

This fact is backed up in the Championships’ own “A Guide to Queuing” pamphlet, which states that “The operation of The Queue, for on-day ticket sales at The Championships, has been designed to ensure fairness.”

Something happens in SW19 when you get in that very specific “Queue”; it’s the sense of what might be, what might happen, of stories not yet written. It is therefore fitting that the phrase “Good things come to those who wait” is traced back to Violet Fane, a British writer—and early Queue visionary—of the late 19th century. My book, Standing in Line, is a memoir based on my decades in the Queue at Wimbledon—it’s almost a love letter. In romantic terms I am Pygmalion; I have fallen in love with a kind of sculpture, in which Wimbledon is the artistic creation, the masterpiece. Or in modern parlance it’s a bit like that woman who fell in love with the Eiffel Tower, or that bloke and his Ford Capri.

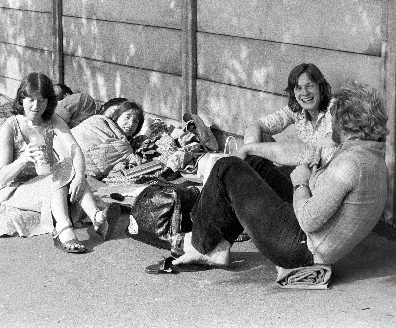

The Wimbledon Queue really came into its own in 1922 when the All England Club moved from the town’s center to its current leafy home, nestled between Wimbledon Village and Southfields tube station. Tennis was heading into its first boom period, and the idea of watching it live caught on like eating strawberries with cream. The images show how relatively little the setup changed until the 21st century, with tennis zealots queuing courteously outside, sipping on tea from street-side carts as they were entertained by street musicians and urchins playing the banjo.

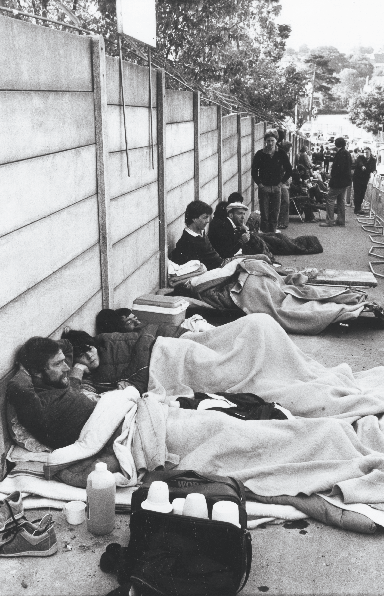

The minor inconvenience of a couple of global wars, in which the Club was actually part-ploughed into a farm, could not stop the game’s growing popularity, and it grew gradually in the postwar period, moving from amateur status to a professional sport. By the time the ’70s rolled around, and tennis entered another golden era, the game had reached a new level of pop cultural significance. The formerly genteel sport went berserk in England, as non-ticketed tennis fans became so obsessed by the game’s new personalities that they took to not just standing, but sleeping outside for the seats Wimbledon would allocate for public sale on the door every day.

• Excessive con- sumption of alcohol and/ or drunken behaviour will not be tolerated and will result in the confisca- tion of your Queue Card and removal from the Queue. There is a limit

of alcohol allowed into the Grounds of one 75cl bottle of wine, or two 500ml cans of beer, or two cans of premixed aperitifs per person. Bot- tles of spirits or fortified wines will not be allowed into the Grounds.

• Please use the litter bins provided.

• Loud music must NOT be played at any time (use personal headphones).

standing in line/topfoto

To a 10-year-old this was incredibly thrilling. I can still remember turning up in ’85 in knee-length Nike socks, a five-sizes-toobig Fred Perry polo (hand-me-down), and a bright red headband/sweatband set. It was a kind of McEnroe-inspired look, rendered largely cosmetic by the fact that it would be four years before I actually started to sweat. A year later and I was allowed, under the watchful eye of my mum and her friends, 10 places down the line, to camp out with my friend Bally (pronounced “Ball-ee,” for tennis reasons). My hobby reached its peak in 1990 when Bally and I turned up on the Sunday before the tournament started and didn’t return home until the quarterfinals, 12 days later. I am pretty sure this is a record. By the late 2000s the Queue on the narrow pavement was so long on both sides of the Club that the decision was made to merge the whole thing into one, thus directing the snaking throng back into nearby Wimbledon Park, towards Southfields.

I have slept an estimated 105 times on SW19’s hard pavement and the park’s soft grass. I have met world No. 1s, legendary commentators, crazed ufologists, rabidly fanatical Federer fans, Australian soap opera stars, and sympathetic, if amused, firemen, who freed my knee from where it was stuck firmly in a queue barrier. I have danced barefoot in the street after a last-minute England World Cup goal, I have cowered in horror as I shared space with a libidinous South African couple, and I’ve eaten a dahi kebab for breakfast with an Indian family. And I have yet to see an altercation, or hear a voice raised in anger. I would still love to have debenture tickets every day through some mad old aunt who owns half of Gloucestershire, but I don’t, and nor do most people. So every year it all comes down to the Queue, that magnificently democratic queue—that’s how we can get access to a world of wonder. And everyone’s invited.

Standing in Line: 30 Years of Obsessive Queuing at Wimbledon by Ben Chatfield, with illustrations by Zebedee Helm, was published in May by Pitch Publishing and is available from leading bookshops and amazon.com.

Ben Chatfield is the author of Mediterranean Homesick Blues. He has written for Wimbledon for seven years, for The Daily Telegraph, and for numerous other titles on the subjects of tennis and Mediterranean Europe. He is also a widely published commercial author working for leading global brands.

Featured in Racquet Issue No. 6