For a time fizzy, and golden in retrospect, we trained with Coach’s favorite boy on Coach’s favorite table. Just like Ryan, we served, pushed, blocked, and looped. We served pendulums forward and reverse, and a hooked Tomahawk that became the club’s specialty. We ran to the haunted yellow house and back. We were the Court One boys.

Every night at Coach’s club was the same. We arrived in the vehicles of parents or grandparents, or in Rahul’s case in the bus that trundled hourly up the hill, past the truck depot and the seafood warehouse. If we arrived before the blackout curtains came down, we stared out toward the cobalt mirror of the South Bay. We unpacked in the bleachers and fooled around until our two-mile run to the yellow house and back. We sat in a circle, crisscross applesauce, and counted up and down by increments to focus our minds: one-fourseven-ten . . . thirty-one, twenty-eight, twenty-five . . . one. Then it was grapevines and ladders and jump rope on the red polyester floor, freshest on our court; multiball, a hundred balls in a row served from a caddy behind our net, the sturdiest, attached to the brightest blue table, where we then rallied, served, and scrimmaged. We were the only ones whose strokes Coach deigned to correct himself, hand cold as he repositioned arm, wrist, elbow. Everyone else made do with the assistants who, having traveled far from their homes in Korea or China or, in one case, Nigeria, lacked Coach’s seamless authority and pulled you around too hard or not at all.

Ryan was never the tallest or strongest of us, only the fastest and most precise. His face was a lean triangle of focus. In excitement his left eyelid fluttered; that was how you knew you were dead. We didn’t remember meeting him, or any of each other. We had always been there, Ryan running three seconds ahead, Alvin leading the rest of us—Rahul, Nicklas, Kevin.

Coach filled our life with punishment. The slowest runner did fifty push-ups; the fastest, Ryan, wore three-pound ankle weights. The slowest drill runner did fifty sit-ups; the fastest, Ryan, did three burpees for every two of ours. The least consistent in multiball and rallying did fifty push-ups and fifty sit-ups; the most consistent, usually Ryan but sometimes Alvin, had to help instruct the rest of us. Anyone who took the elevator, down into the basement or up to the third-floor weight room, ran to the yellow house and back. Anyone caught drinking Gatorade out of the ancient vending machine ran to the yellow house and back. Coach never shouted, just informed us, calm as a judge, in an irrefutable and almost pleasurable way, how our lives would worsen. Alvin said Coach was like a Chinese Face Changer: hidden by a mask beneath which could flash, at any moment, a demon’s hooked teeth, the rippling hell-red skin of a horror movie villain. Or like Orochimaru, the snake ninja in Naruto, whose split head, right when you thought you’d killed him, regenerated a stolen body.

We accepted everything with equanimity—partly in imitation of Ryan, who never complained, as Coach corrected his every stroke and loomed over him to count sit-ups and pulled him aside at the fountain or into his office to remind him how much better he must be, that he had it worst, though we knew his stoicism was a result of his talent, not the other way around; partly because punishment was the way of our world, in practice and out.

Relegation was the only punishment we feared. Every Thursday, the club’s busiest night, Coach relegated one of us—usually whoever lost the most scrimmages that week, or messed up the counting game most often—to Court Two, with Assistant Coach Haesun. In descending order, the best table tennis countries were China, Sweden, Japan, Germany, Korea; what a downgrade from German Kristian to Korean Haesun, from training alongside Ryan to writhing in the morass of lesser boys! The relegated slunk up to us during water breaks, begging for the merciful illusion of having been included in the night’s jokes. If we felt benevolently powerful, we granted it. If we felt malevolently powerful, we teased: What’s it like down there? How does losing smell? If we felt disenfranchised, we ignored him altogether, perhaps the cruelest outcome.

Did this ultimate humiliation sometimes bring out the desire, normally tamped by modest success, to usurp Ryan and claim Coach’s affection? Did it make us think we understood what powered Ryan’s arm as he hit multiballs onto the white lines that circumscribed our lives outside school, that we could have done that, too? Did we suspect that Coach relegated us not for purely economical reasons, but to drum up this very feeling, without any real intention to pick one of us instead? Yes.

But for now, that diverged not at all from what we felt we deserved.

Outside the club, the world turned onward.

The war started.

The lights blacked out on the East Coast.

The president was reelected.

Ryan was relegated three times.

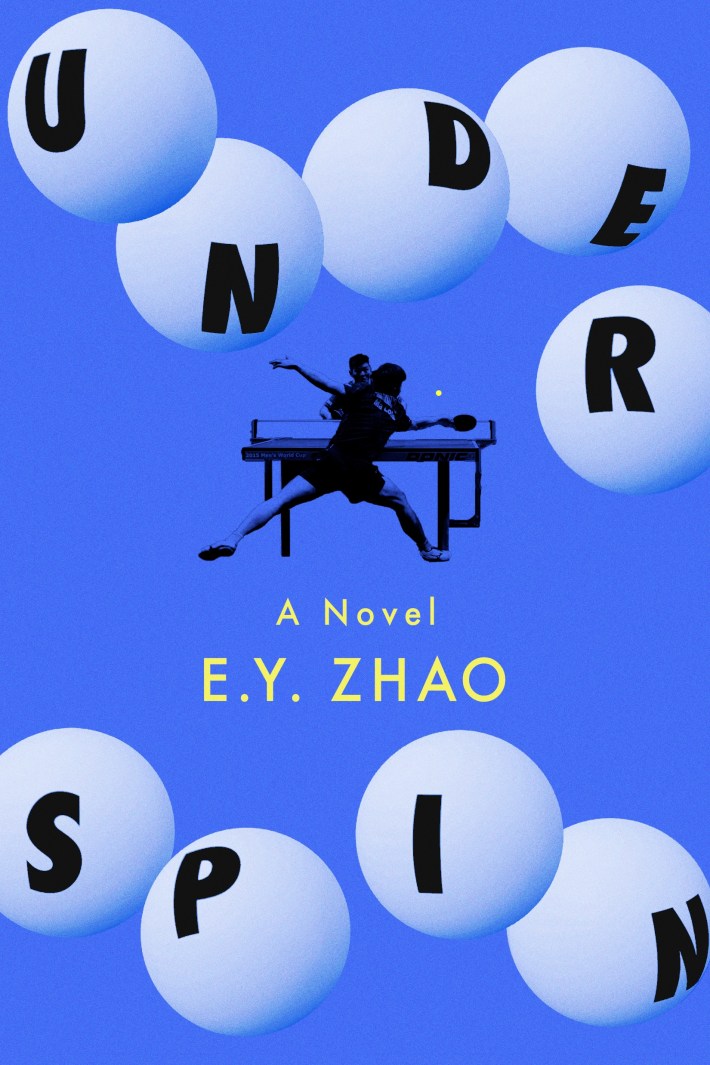

Underspin is available everywhere on September 23. E.Z. Zhao lives in Brooklyn, NY, and serves as an editor of Joyland.