For those of us raised on the mythologies of tennis—the cathedral of Wimbledon’s Centre Court, the late-night giddiness of Arthur Ashe and the chic red clay backdrop of the European swing—the emphasis on professional singles can outshine other constellations. But at Racquet, we proudly celebrate tennis in all its forms, from the public court rec league to the super seniors battling it out in the ‘80s divisions. As the best athletes in the world gather at the slams, all the professional divisions—doubles and mixed, legends and juniors, and especially this year wheelchair tennis—draw much of our fascination. In 2025, as the US Open celebrates two decades of wheelchair competition, we spent a week in New York listening to legends and upstarts alike, festival-goers and family, tournament directors and kids peering through the gates, finding that for many the heart of the tournament beats strongest where the wheels spin fastest.

For quad athlete Andy Lapthorne, it’s no surprise that the US Open is the slam to break new gound: “It feels like the working-class slam,” he tells me. The Knicks are his team and the Open is his home away from his London-based training center. “I’ve hustled, I’ve fought for everything. This place suits me down to the ground.”

Wheelchair tennis at the US Open, now celebrating both its 20th anniversary and its suite of firsts—first to offer a quad draw, first to open the doors to juniors, first to treat players as main characters, not afterthoughts—could only have happened here, in a city that expects reinvention to be ordinary .

Tokito Oda, the sport’s swaggiest new star, won this year’s men’s WC singles title and in doing so, clinched a career golden slam—winning all for majors and an Olympic gold medal—before his twentieth birthday. Off season, he’s busy doing commercials in his native Japan and racking up teenage fans in Paris, but it’s his country’s legacy in the sport—led by the legendary Shingo Kunieda, who retired after the 2022 season as the greatest WC men’s player of all time—that he’s thinking about the most. “When Shingo retired,” he says, “I felt like, now I must do more for wheelchair tennis.”

Maylee Phelps, 18 and newly minted in Nike blue, shrugs about her lucky shoes (“tucked away in a closet”), less entranced by stylings and more by the accelerated pace of the women’s game. “Transitioning from juniors to women’s—it’s a big one. Everything’s faster, everything’s more tactical,” she says, eyes sharp but undaunted. “Juniors, you just hit to hit. The women, you need tactics. Know your opponents. Have a mental game.”

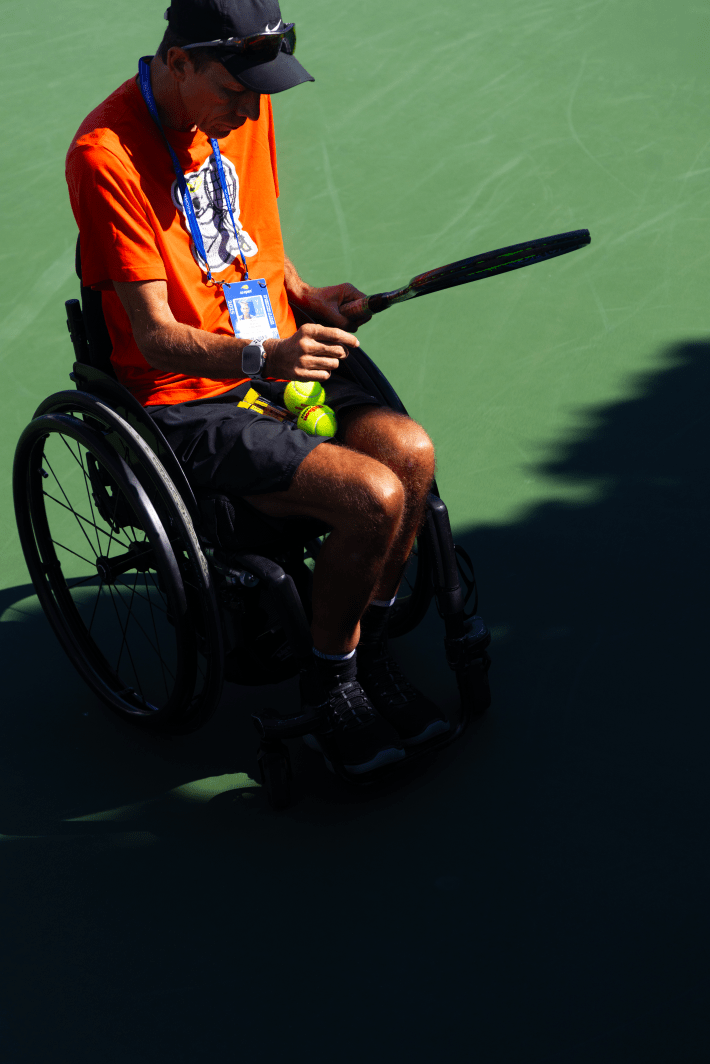

The normalcy of the parade of players—wheelchairs festooned with Yonex and Babolat equipment, chair-wheels scuffed and bananas and recovery gels overflowing kit bags—can obscure the fact that the kids coming up now know nothing but Grand Slams, equality in draw sizes, and prize money that, Kunieda, who now coaches the rising wheelchair talent as a coach at the USTA’s national campus in Orlando, Florida, reminds me, is “almost twenty times” what it was in his first time here. “But if there’s not the players, and the staff, and the history—no one could be here,” he adds. The lift is generational, literal and figurative; the path hard-won and meticulously paved.

“Don’t forget who came before,” Jason Harnett, Head Coach of USTA Wheelchair tennis repeats, more mantra than request, as we chat beneath a cluster of concrete overhangs. The WC program has gone from patchwork to powerhouse, with collegiate opportunities booming (fifteen programs, up from two) and kids now dreaming of the next big match under the lights. “When I came in 2016, that was my focus. Real perspective,” he says. “This generation—they only know large prize checks, four Grand Slams. The next generation will know nothing but that.”

There's nostalgia in the air, but not the kind that pulls us backwards. Instead, it’s a reference point; the old guard like David Hall and Esther Vergeer, hovering between mentor and idol, watching the upstarts storm through early rounds and media days. It’s not about celebrity, not even about legacy: “To meet, to see, to hear—a kid needs a hero who sounds like them, looks like them, rolls like them,” Harnett says. “Not just reading about them. Direct conversation. Seeing them.”

Charlie Cooper, fresh from winning the junior US Open last year and now competing is his first men’s WC main draw, framed it like this: “When I started, people were winning slams at 25, 27. Now you see Tokito Oda at 17—winning a slam.” The chain reaction is already underway, further accelerated by Kunieda, who, in both body and voice, embodies the transition—legend to coach, player to mentor—learning and teaching all at once. “Every player is different,” Shingo muses. “I must be flexible, its always a conversation.”

Ask Cooper about working with Shingo and words like “blessing” and “father figure” surface, rare vulnerability bubbling alongside fierce pride. “He never lets me in it, ever. Even in practice. If I don’t hit a good shot, he’ll tell me—it’s not good enough. He wants me to be at that level.”

Nowhere is the game’s current tension more visible than in Andy Lapthorne’s division, the Quads. “At two slams we don’t have equal draws. Here, we’re treated equally.” The relish—and the relief—isn’t lost on him. “It’s not just a checkbox. Here it’s part of the event. Not an add-on.”

Lapthorne makes time for Kids’ Day fans and shared sandwiches with fellow players. But ask him about the future, and the realities surge: “The numbers aren’t there, they say. But how can they be, if you don’t give enough opportunities? Increase the draw, offer qualifying events, get finances so these guys can chase the tour. If eight guys go off to the ATP but there’s no tour for juniors—no sport left in 15 years.”

The best part might be how unselfconsciously ordinary this all feels. Jason Harnett is quick to remind me: “We’re past the point of people not knowing about wheelchair tennis. The quality, the training, the television coverage. These kids expect this now.” The requests for better funding, bigger draws, media days—ordinary demands for ordinary equality.

Even in this ecosystem, old baggage remains: “Not everybody understands disability. We push hard for this. Past bean counters, skeptics,” Harnett sighs. But the mood is: LFG. The new kids are here, and they’re not just bringing booming serves and groundstrokes—they want the full measure of what tennis promises: a world open to all.

By week’s end, there are flowers in the garden, selfies in front of stadium murals, old hands guiding the new, and, at last, the stadiums and trophy ceremonies for the winners. As the kits and wheels glint under the glare, Wheelchair tennis in many ways, tennis here is bustling with a workaday ordinariness—a clear-eyed faith in better draws, fatter wallets, and, above all, more tennis for more people.