Illustrations by Luke Shuman

The Dubai Duty Free Tennis Championships is a high-quality tournament hosted in one of the coziest, most understated settings.

I remember the first time I walked around the Aviation Club in Dubai, almost a decade ago. I was taking a stroll across the cobblestone, making my way through the bars and restaurants that lined the perimeter and thinking to myself that this has got to be the cutest little tennis venue on earth.

On one side of the main stadium there’s an Irish Village, an outdoor pub with wooden benches and live music, which has been a popular spot year-round for the past two decades. And there’s a small garden nearby that has scattered beanbags where people can hang out, sip beer, and watch the tennis on a large screen—or feed the ducks in a nearby pond.

In a city that deals only in extremes—having the biggest, fastest, tallest, fanciest of everything—this small tennis club in the heart of Dubai feels like the antithesis of all that. Yet it successfully plays host to an event that elevated the status of the emirate, placing Dubai firmly on the global sports map, which is precisely what the state’s rulers set out to achieve by staging this tennis tournament to begin with.

On the sidelines of the 2005 Dubai men’s tournament, a stunt video of Roger Federer and Andre Agassi playing tennis on the helipad of the seven-star Burj Al Arab hotel went viral—organizers claim 3 billion people have watched it—and it put the event and the city in the spotlight like never before. The powers-that-be in Dubai had a strategy, and it was working.

But as the tournament—and Dubai—grew in stature, receiving rave reviews from the top players each year, the fact that no Emirati tennis talent emerged as a result was both undeniable and peculiar. Privately run facilities and academies popped up in large numbers around the country, but they were mostly catering to foreign residents, not locals.

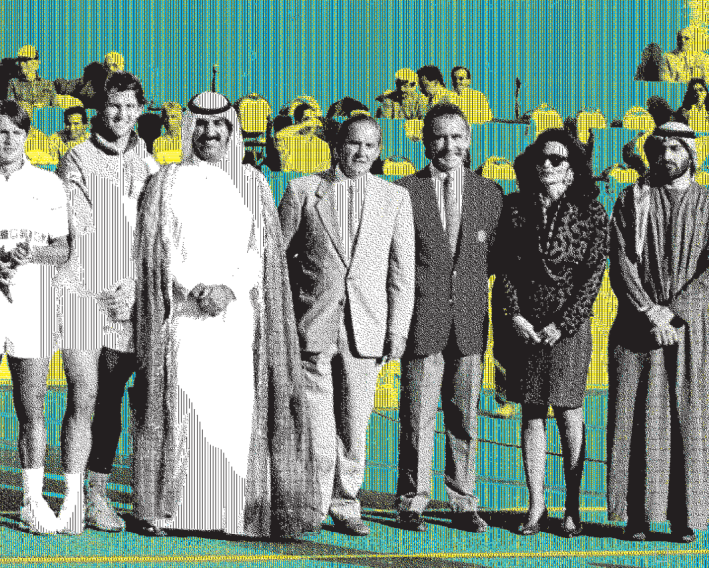

The professional circuit came to the Arabian Gulf region in 1993 with two new ATP tournaments held in Doha, Qatar, and Dubai, UAE. The vision of Sheikh Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum, the ruler of Dubai and the vice president/prime minister of the country, was to bring some of the biggest sporting events in the world to the emirate in order to raise its status and relevance globally. He also believed sports tourism would benefit the country greatly, and he was not wrong.

Tournament owner Dubai Duty Free offered up total prize money of $1,000,000 for the inaugural edition in ’93, which was almost double what other events of the same tier paid, and organizers went above and beyond to spoil the players, putting them up in fancy hotels and catering to their every need. Karel Novacek, a former world No. 8 from the Czech Republic, beat Frenchman Fabrice Santoro in the event’s inaugural final.

“They put on a great spread to greet us at the Aviation Club of Dubai,” recalled Novacek in an interview with www.wearetennis.com. “Really, they did what it took to make us speak well about the tournament to our colleagues on the tour,” he said. “We felt all their ambition to become a state that mattered internationally.”

There was understandable skepticism regarding the tournament at the start, with the Arabian Gulf having virtually no tennis tradition. The top seed in 1993 was ranked No. 17 in the world. Today, both the men’s and women’s weeks regularly feature at least four or five top 10 players.

Each year, the facilities and perks have dramatically improved, to the extent that Dubai Duty Free built an on-site five-star hotel, which has been hosting the players, their teams, and invited media since 2013.

But while the Dubai showpiece consistently attracts the Federers and Djokovics of the world, the local talent is nowhere to be seen. The tournament celebrates its 25th anniversary next year, yet within that quarter of a century, no Emirati male or female player has risen through the ranks.

The nation’s sole ranked player is a 34-year-old called Omar Behroozian, who is currently hovering in the 1,600s and peaked at 805 back in 2003. Behroozian has been considered the UAE’s top player for the past 15 years and was given a main-draw wild card nine times between 2001 and 2012.

He has won an average of 3.4 games in each of the nine first rounds he lost in his home city. With a serious dearth of local prospects,

the occasional beneficiaries of wild cards are other Arab players who are in desperate need of opportunities like this.

Fatma Al Nabhani, from the neighboring Oman, is the only man or woman from the Gulf region ranked in the top 500 and is the first professional female to emerge from the Gulf. The 25-year-old is an anomaly, especially growing up in a region that has cultural barriers that discourage women from taking up sport. But there is a reason she is that one exception.

Al Nabhani grew up in a tennis-playing family; her mother, who is Egyptian, planted the tennis seed in her and her brothers, Mohammed and Khaled. Growing up in Muscat, Oman’s capital, there were never enough girls to make up a full draw for a tennis tournament, so Al Nabhani would compete against the boys and defeat them. She was ranked as high as 33rd in the world as a junior and reached the top 400 in her first year as a pro.

With Oman being driving distance from the UAE, and Al Nabhani being a true “Khaleeji” (someone from the Gulf) trailblazer, she should be an obvious choice for Dubai when it comes to allocating wild cards, but in the 10 years she has featured in the tournament, only once was she given a spot in the main draw; all other nine invites were for the qualifying rounds.

Al Nabhani has attended the event since she was 5 years old, and is puzzled by the fact that no local Emirati has managed to emerge on the tennis scene during the 25 years of the tournament’s existence. “I feel they stage this tournament for a different reason, not for the purpose of developing UAE tennis,” says Al Nabhani. “The tennis federation in the UAE plays a very small role in this tournament. The only thing they do is the kids’ day, and you see some young Emiratis taking part. I wish hopefully that they could do something about it to improve the tennis in the UAE, but I feel that the expats benefit more than the local people from this tournament,” she says.

The key word here is “expats.” The UAE population makeup is unique, with Emiratis amounting to just over 10 percent of people living here, the rest all being foreigners. Most expats treat Dubai as a transient stop, and many spend just a couple of years there before moving on to someplace else.

Building a lasting legacy in a population that is continuously changing has been a challenge.

As for the Emiratis themselves, not enough is being done to get them interested in tennis, and those who are interested have no place to go train since the federation has no national tennis center to cater to its players. “Obviously that doesn’t make sense at all,” Tunisian Selima Sfar, the only Arab woman to ever crack the top 100, says of the lack of facilities dedicated to local UAE players. “It would be hypocritical of them to ask the question ‘Why are there no players?’ because the answer is so obvious: You’re doing nothing to have a player, basically.

“There are so many academies in Dubai—the facilities are great, but all of them are private. I think step No. 1 is for the federation to have a center where you welcome the players and you make sure that they are around the right coaches, which is the hardest thing,” Sfar says. “You have to give them the right environment. It’s also very important to spread the culture. It doesn’t come overnight.”

The 39-year-old Sfar, who is now retired and works as a commentator for beIN Sports in Doha, was ranked as high as No. 75 in the world in 2001. Her parents are both doctors, and she had no frame of reference as an young Arab girl looking to pursue a career in tennis, so she left her home in Tunisia when she was a teenager and moved to Biarritz to train alongside Nathalie Tauziat, who is French.

“It’s difficult for us as women,” Sfar says. “For me, I had to leave my country and my family at 13. So first of all I had to have a family that has enough money to support me, because it’s very expensive—to accept to send me abroad, with no examples to follow. Let’s say there are 10 Tunisian or 10 Arab women who made it before me; that would have made it easier. And if anybody judges you and says, ‘You’re crazy,’ you can say, ‘Come on, they did it, so can I.’ Nobody did it before me.”

In many Gulf states, the cultural obstacles to overcome when it comes to women competing in sport are tough to tackle, and they start with something as simple as an outfit.

Wearing short skirts and sleeveless tops does not necessarily conform to Muslim attire, but Al Nabhani found a work-around that made her feel comfortable while playing. During competition, the Omani wears leggings underneath her skirt and dons a long-sleeved shirt. She is sponsored by Nike and says she’s lucky they offer the styles she needs to complete her special kit. “Obviously when I was in juniors and I was younger, I used to wear skirts and play normally. Later on, just for me to be comfortable and to respect my culture and where I come from, I tried to create my own style, and thankfully it’s approved by the ITF and the WTA,” Al Nabhani says.

“I’m so happy because I created my own thing and a lot of other girls from the Gulf now feel encouraged to play tennis knowing they can cover up a bit and play in something that’s comfortable for them,” Al Nabhani says. “But the thing is, whenever I go to tournaments abroad, every single time, all the girls ask me, ‘How the hell are you playing like this? It’s so hot.’ But your body is used to it. I don’t feel I’m hot when I’m playing in it. I’m comfortable.”

Both Al Nabhani and Sfar are used to fielding questions about where they come from. During a talk arranged by J.P. Morgan at a Dubai event last year that brought together local Emirati women and professional players, Sfar was asked if she ever faced trouble as an Arab woman traveling around the world for her sport. “Yes, I did,” she said, “because when you go to the States or Europe, because they haven’t seen Arab female tennis players before, they don’t know, they look at the Arab world or our culture or our religion and sometimes they have the wrong image. In a way you’re like an ambassador to show to the rest of the world that of course we can do sport, we are free, we have exactly the same possibilities.”

The main issue that affected Sfar during her playing days was trying to obtain entry visas for all the countries she had to travel to. It is a continuous struggle for Arabs who need to travel for work to this very day. “Sometimes I missed so many tournaments because of visas, and if I didn’t miss a tournament, I’d miss three days of practice because I’m queuing at the embassy to get my visa,” she says.

Younes El Aynaoui, the Moroccan who is the most successful Arab tennis player in history, says that combining sport and studies needs to become a viable option in a region where many parents encourage—or force—their children to give up sport in favor of academics by age 16 or 17. The 45-year-old, who peaked at No. 14 in the world in 2003, pursued a career in the sport against his parents’ wishes and ended up reaching four career Grand Slam quarterfinals. “I was an excepion. I didn’t listen to my parents, I was a bad son, at one point I went against them,” says El Aynaoui. “My brother is an economist; he works in the Bank of Morocco, and he listened to my dad. I gave everything for the tennis and, thank God, if I had to do it again, I would do it again.”

Despite the challenges, El Aynaoui is nevertheless baffled by the lack of players emerging from the Arab world. “I’m surprised that in the Middle East you don’t have more players, because those tournaments”—in Dubai and Doha—“it’s almost been 25 years now since they started. I had the chance to have one big tournament in my life in Morocco and that was it. I said this is what I want to be, I want to be part of this tournament one day, and that’s how my dream came true,” he says.

The UAE tennis federation, Tennis Emirates, has little involvement in the Dubai ATP/ WTA events even though the tournament director, Salah Tahlak, is both a Dubai Duty Free employee and a board member of the country’s sports governing body. According to federation secretary general Sara Baker, Dubai Duty Free offers Tennis Emirates financial support for development, and several grass-roots projects are already under way. “Our only problem right now is finding female trainers that speak Arabic. There are lots of English-speaking coaches, but when it comes to locals, if we were to go to public schools, you’ll have to have someone who speaks the Arabic language in order to do that,” Baker says.

For the pros, though, Dubai is an oasis. The emirate has become a prime destination for players during the off-season. I recall walking through the grounds of a beach resort here several years ago and accidentally finding Federer, Kim Clijsters, and Svetlana Kuznetsova all training side by side, preparing for the new season. Novak Djokovic, Jelena Jankovic, Andy Murray, Ana Ivanovic, Angelique Kerber, and many more have spent time in Dubai practicing, making use of the immaculate courts and facilities available to them at the hotel of their choosing.

Federer bought an apartment in Dubai almost a decade ago, and he’s been a regular here ever since. Many others have followed suit, with the latest being Lucas Pouille, who lives just a couple of buildings down the road from the 17-time Grand Slam winner.

It is hard to understand, though, how such superstars can spend so much time here without anyone thinking of a clever way to utilize their presence in a manner that could benefit young local talent. Instead, the focus is once again on the big tournaments, and how they can possibly get bigger. “I have a vision, if there is ever a fifth Grand Slam, then I would like it to be in Dubai,” Tennis Emirates vice president Abdulrahman Falaknaz told Gulf News.

Dubai may be lacking in several areas— local tennis prospects, national facilities for Emiratis to train in, a coherent development program—but ambition is certainly not one of them. Time will tell how far it can take them.

Reem Abulleil is an Egyptian sports reporter for Sport360˚ in the United Arab Emirates.

Featured in Racquet Issue No. 2