A Basement Champ Takes His Game to China, Where Table Tennis Is No Hobby—It’s a Way of Life.

By Robin Goldstein

I was always an above-average pingpong player. In junior high school, my parentsfinally recognized my talent and bought me a table. They put it out on thescreenedin porch. This was Western Massachusetts, and it was cold as hell out there in the winter, but my friend Eric and I played in our parkas, with feet of sticky snow around us and through months of dark brown slush.

In tennis, Eric almost always beat me. We both made varsity in our sophomore year. He broke in at No. 4 singles and I was No. 5. In our challenge matches, he and his widebody Wilson Hammer always had some extra gusto for me and my even-wider-body Prince CTS Thunderstick, which my mom bought me in an unsuccessful attempt to help me beat Eric, and I spent my next three years on the team exactly one step below wherever Eric was on the ladder.

Back home, though, the ping-pong table was mine. My lifetime winning percentage against Eric, over several seasons of series, was at least .550. Our exhilarating games recapitulated the ones on the tennis court—we even served and volleyed—but with the humiliating outcome reversed. It was for this, and not just for the hypnotic grace of our accelerating crosscourt forehand rallies, that I loved ping-pong.

In the high school TV lounge, as a freshman, I could stay on the table against processions of muscular seniors, the overconfident quarterbacks and linebackers, laughing as they served balls from their hands while leaving their weak backhand corners undefended.

I played in hopes that Heather, who had bangs and curls and ice blue eyes, would notice. But the one time she saw me hit a three-pointer in a JV basketball game impressed her more than the sum of all times I stood there at the ping-pong table, in my varsity-tennis letter jacket, shellacking schoolmates of all ages.

I was raised in Northampton, where men have a different way of expressing themselves. My father, who has a rolling belly laugh and a big gray beard and wavy white hair down to his shoulders, once bought me an anatomically correct male doll. My dad doesn’t play any sports. My mom taught me tennis. SoonafterIlearnedtowalk, though—and well before I ever picked up a racquet—my dad started taking me out into the backyard almost every day to play catch with a tennis ball. He wouldn’t stop until I learned to throw and catch. He did for me what his father never did for him. He built me a basketball hoop in the driveway, penciled in the power-sawlines and painted it cream and blue to match the house. The plywood backboard was flexible enough to absorb almost all of the ball’s forward momentum, giving the hoop a submissive touch.

My dad took me out into the driveway and taught me to shoot jumpers with equal weight on the left and right hands, like a throw-in.Heatherneverunderstoodthe many barriers I had to overcome before hitting even a single three, defended, in front of anatomically correct girls.

The college ping-pong team held practices on Thursday and Friday nights at 10 p.m., which didn’t mesh well with my schedule of learning to drink. By my early 20s I was in the twilight of my ping-pong career. Or so it seemed for the next two decades before I met Jing, who is now my fiancée. She had silky brown hair and great big lips and played viola like she was delivering a message directly from God.

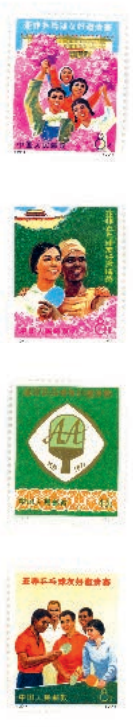

In 1959, pingpong player Rong Guotuan became the first Chinese athlete to win a world championship in any sport, earning him a place on a postage stamp.

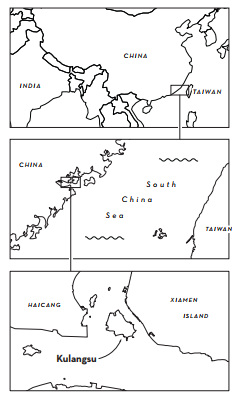

Jing comes from a fairy-tale subtropical island called Kulangsu, technically just an islet, with 20,000 permanent residents but 10 million visitors per year, 96% of whom are Chinese. Tourists come for the romance and the beaches and the smallness: Kulangsu is 1.8 square kilometers of land out of time, a pedestrian-only thicket of hilly cobblestoned pathways lined with faded 1930s Mediterranean villas covered with ivy and banyan trees with beards that hang low like Spanish moss. Kulangsu is part of the prefecture of Xiamen, a larger island and probably the friendliest city in China. Like Kulangsu, Xiamen is a winter haven, blessed with Miami weather and palm trees and laid-back locals who play street music beneath ancient temples hanging from giant rocks.

None of this was the way I’d pictured China before I’d been there. My prior impression of China, which I had formed from watching the lower tiers of Olympic events that aired on time delay in the middle of the night, was simply that it was the world’s dominant ping-pong force.

When Jing first asked me if I played pingpong, I said, “Yeah, I play a little bit.” I didn’t want to be presumptuous; I didn’t want to mention how long I had been waiting for this moment, or that I had always imagined her country to be a kind of ping-pong paradise, where the ping-pong champion was the most popular boy in school.

We were at an outdoor table at a hazy beach resort on the shores of the South China Sea. Jing and I picked up our paddles and hit some crosscourts. I relaxed when I saw that she served the ball out of her hand like a high school quarterback. I shouldn’t have assumed she knew how to play. I was a racist. She boinged the ball to me like we were playing four square, and I scooped it back like a gentleman, a pusher, like one of the kids from Longmeadow High who would bloop the ball back to you with the throat of his racquet held at a 90-degree angle to the ground and then complain of a leg injury in every set where he fell behind five games to three.

But eventually there came one ungentlemanly moment when, by sheer instinct, I hit out on the ball. It was dropping off the table to my right, and the only return I had was a hard, steep crosscourt angle. In the split second of ball off my bat, I could see Jing’s mouth twisted open in surprise, her brow furled, comprehending what was happening to her yet frozen by it. She quickly recovered, however, and wailed a nasty slider deep to my backhand, curling hard left, almost skidding off the edge of the table, and leaving me with no option other than a gasping lob that was soon finished by my fiancée with a triumphant slam to the ceiling.

After this, Jing came over to my side of the table and made several adjustments to my posture. She explained that I was playing ping-pongcompletelywrong. Sheshowed me the correct way to hit the ball: with a compact, rhythmic motion that was a bit like Latin dancing and was not in any way similar to the flailing tennis stroke I had been using.

In game play, I quickly learned that Jing hits hard as shit. She hits a hard topspin forehand, and an even harder topspin backhand. Still, she’s bored with these weapons. She asked me to teach her how to hit a backhand slice like we New Englanders do, and after a lot of practice she got pretty good at it. After she did, one day she stopped and asked me: Actually, why do you hit that kind of slice?

In tennis, the slice backhand, if overused, can have a strategic purpose. In ping-pong, where slowing things down is putative surrender, there may be none. When you’re forced to cut the ball’s speed to reverse its spin, the extra half-second is enough time for your opponent to get cognitive. You don’t want that. Give up the table and you’re done. Your only chance is to stay in front, turn on the ball, sway your shoulders, rotate your chest, hit over everything. You make the table your cave.

Topspin backhand, though. Not even the great E. Jackson Hall, the only guy in high school who had vicious answers to all my ping-pong tricks, or Crazy Eddie, the old Pole who would beat me every year by about the same score of 21–16 in the finals of the summer camp tournament in Lake Winnipesaukee, had a topspin backhand. Never in all of New England had I seen a real topspin backhand until I met my lady.

I had always thought that “ping-pong” was the informal name for what had originally been called “table tennis”—until I looked into the matter and discovered that this could hardly be further from the truth. Like badminton, the other Chinese national sport, ping-pongwasinventedinIndia,around 1870, by British tyrants, as a parlor game for the idle rich. By the turn of the 20th century, the sport had already migrated to the colonial motherland and assumed its more-or-less current form, with the onomatopoeic name, pimpled-rubber-on-wood paddles, and celluloid balls. Huge tournaments were being organized and drawing crowds.

Industrialists soon took notice,andan English company called J. Jaques & Son, Ltd.claimedownershipofthenewsport and registered the “Ping-Pong” trademark in London. Jaques then sold the trademark to Parker Brothers of Salem, Mass., which did its board-game pedigree proud by trying to force everyone else in the world to change the name of the sport to “table tennis” when it was played with anything other than Parker Brothers’ licensed equipment.

The text from the box top of the company’s 1920s consumer set points toward the forward-looking fervor of Parker Brothers’ intellectual-property attorneys:

CAUTION:PING-PONG alwaysbears thefamousandregisteredtitlePINGPONG upon the box, rackets, net and balls and contains the official LAWS of PINGPONG. (Adopted by the American PingPong Association)

A century later, U.S. sports monopolies would turn out to be a highly successful business model, but Parker Brothers’ early effort to claim the global ping-pong market for America was doomed by its geographical and legal limitations. The non-infringing International Table Tennis Federation (ITTF) was established in 1926, and by the 1930s, the Red Army had already fallen in love with the sport, with its brave soldiers honing their precision motor skills at the table in preparation for the terrifying battles of the Chinese Civil War. Not privy to the intricacies of Western imperial trademark law, China adopted the beautifully hieroglyphic word 乒乓 (pīngpāng). The nationalists of Parker Brothers, and the ones in the Kuomintang, were done. Ping-pong is for the people.

In the early 1950s, Chairman Mao—by all accounts a good player himself—declared pingpong the official national sport. China soon joined the ITTF, and by 1959, the player Rong Guotuan was on a national postage stamp as the first Chinese athlete to win a world championship in any sport. The 1971 visit of the U.S. ping-pong teamto China,a.k.a.“ping-pong diplomacy,” is widely credited with enabling Nixon’s state visit to China the following year and the subsequent opening of diplomatic relations between our two countries.

China’s behavior at the Olympic Games has been less diplomatic. No Olympic sport is more dominated by one country than ping-pong. None other even comes close. China has claimed 48 of 54 gold medals ever awarded since ping-pong became part of the Olympics in 1988. In Beijing in 2008, on their home tables, the Chinese ping-pong team still managed to accomplish a new feat: sweeping all six medals in both men’s and women’s singles. In response, the Olympic committee made a new rule limiting the number of singles competitors per country to two. In both the 2012 and 2016 games, China thus had to settle for all the golds and silvers, but no bronzes.

And the American intellectual-property lawyers still haven’t given up the fight. The trademark for “Ping-Pong,” U.S. Class 022, International Class 028, “Game Played With Rackets and Balls,” registered Aug. 1, 1900, is still being actively enforced by its latest owner, Indian Industries, Inc. of Evansville, Ind., founded in 1927 as Indian Archery and Toy Co., now d/b/a Escalade Sports, the current manufacturer of the little-known PingPong™ brand of table-tennis gear. Amongst Indian Industries’ most notable 21st-century legal victories was the successful seizure of the domain name pingpongmania.com from the Ping-Pong Mania & Sporting Goods Co. of Bloomfield, Conn.

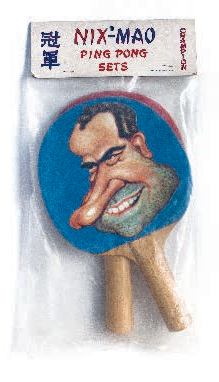

The 1971 visit of the

U.S. ping-pong team to China is widely credited with enabling Nixon’s state visit to China the following year and the subsequent opening of diplomatic relations between our two countries, in addition to inspiring a cottage industry in cheap ping- pong-related tat.

Jing came over to my side of the table and made several adjustments to my posture. She explained that I was playing ping-pong completely wrong. She showed me the correct way to hit the ball: with a compact, rhythmic motion that was a bit like Latin dancing and was not in any way similar to the flailing tennis stroke I had been using.

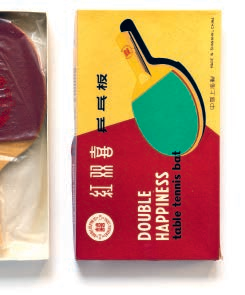

On one occasion, I arrived in China to a carefully wrapped gift from Jing. She whinnied and I removed from the package two smooth heavy paddles. They had inlaid wood handles, one red, one blue, both hard and smooth enough to make handle-rubbing a valid leisure activity. Attached to each of these wondrous pieces of wood was the stickiest and most expensive Butterfly rubber on the market.

Before we started playing, Jing warned me: These paddles are fast. They’re professional. By this she meant that at first, and for a while, it would remain physically impossible to control the distance between the paddle and the place where the ball lands after being sprayed in a semi-random direction off its rubber launchpad with almost inconceivable elastic force. My empirical conclusion, after a few months of experimenting, was that it takes any ping-pong player, regardless of skill level, at least five minutes of hitting with one of these springboards to train his or her motor cortex on the massive adjustment to the outputs and air-reprogram a lifetime of muscle memory. The initial effect is that the player hits every single ball off the table lengthwise by at least two inches. In this way Jing and I, who frequently travel around China with these paddles, are able to hustle some of the hotel pickup players who would otherwise crush us.

Where the expensive paddles shine most is when you’re playing around true nonprofessionals. Far away from the high-grade rubber floors of Xiamen’s elite ping-pong clubs, at a table on the convention-center floor of a mental-health conference in Vegas, for instance, the sonorous pop of Jing’s monster backhand will reliably draw two-deep crowds of murmuring Caucasians, eyes in synchrony, camera sticks craned, tennis-trained brains struggling to fathom how this girl’s balls can possibly travel so fast.

Jing may still be an amateur baller, but as a musician, she’s a professional. She plays viola and violin as a soloist with orchestras and also teaches a few private students. By music standards, she’s well paid for her work— or would be if she didn’t spend most of her disposable income on other teachers. Her ping-pong coach, whom she pays as well as herself, is a former member of the Chinese Olympic training squad. Jing spends a huge portion of her earnings on teachers: golf lessons, tennis lessons, kitesurfing lessons, jazz piano lessons, viola lessons from her old conservatory professors. Last year, Jing installed a weightlifting device in the middle of our living room that hung like a noose from the ceiling, and a giant mirror next to it that reflected the noose. She explained that these had been recommended by her fitness and hip-hop-dancing instructors, respectively.

I have never seen a land that respects teaching more than China does. The Chinese use the same term of honor, “lao shi,” for the fullest professor and the most part-time instructor. It is not just the attainment that is exalted, but the simple act of teaching. The term serves the purpose of recognizing that in the annals of human natural law, teaching is a super-precedent. Everywhere we live, whatever we believe, education is our one history. The tale it tells is the only tale we know.

I was excited when my Xiamen friend Empire Huang invited me toplayinmyfirst Chineseping-pong tournament. At first I sought advice from Jing’s coach. My form couldn’t be fixed, so he told me to keep just one thing in mind in match play: Hit it to your opponent’s backhand.Leaveit on the forehand side with anything less than a screaming topspin strike at a sharp angle, and you’re fucked.

The tournament venue brought even more rare gifts from paradise than I expected, like digital scoreboards and uniformed referees. Other than games being played to 11, win by two, two serves per service, I couldn’t understand the logic of the group round or the basic structure of the tournament. After winning one match and losing two, I was told that I had progressed to the elimination round. It was explained to me that this had happened on the force of one or more defaults, but I suspected meddling in my favor on behalf of the organizers, who were honored to have a foreigner participating.

In the eliminationbracket,I hadthebadluck of drawing Empire Huang. This I believe to have happened by accident. Empire is a slim, smiley, freckled man with the nerdiest glasses in China, and he is possibly the most generous man I have ever met. Fortunately for my gear and unfortunately for my chances of advancing, his profession is ping-pong equipment salesman.

Within a few hours offirstmeeting me, some months earlier, Empire had given me a state-ofthe-artJoolaspandex competition ping-pong suit.

More recently, Empire delivered and installed a professional ping-pong table at a hotel on Kulangsu for an event for Jing and her viola students. This involved taking the pingpong table through a ferry terminal and past an airport-style security checkpoint, which was tightened when Kulangsu Island was named a UNESCO World Cultural Heritage Site in 2017. The table then had to be taken on a short ferry ride and banged up a gangway that was steepened by low tide.

Next, Empire had to roll the ping-pong table 15 minutes up and down a series of small cobblestoned mountains on the pedestrian-only island and climb two flights of stairs to reach the hotel courtyard. At some point we were all hanging out in the courtyard and Empire came by with the table, opened it up, put up the net, waved, and left. After the event was over, he told us to keep the table.

img

Under the Joola banners, before the camera crews with booms, Empire Huang’s many gifts flashed before my eyes. He tossed his warm-up jacket on the table next to the ashtray wherehe kept the cigarette that he smoked between points. Empire generously offered to let me serve first. I’d taken a game from him the last time we’d played, so I gave myself a chance.

I breathed in and led off with my high heat, the North American flat serve, which is technically legal (I throw the ball in the air before hitting it) but otherwise so unlike any serve seen in China that it has become the unintentional trademark of my game. I hit a decent one, deep to his backhand (as instructed), and all Empire could do was block the ball back, spinning it barely over the net and leaving it for me to put away.

My slam went directly into the bottom of my side of the net, just to the right of center. After my next three shots ended up in the exact same spot, I understood that it wasn’t just my nerves. From 0–4, game 1, I could already see straight to the abyss. This was Empire’s house, and I was even wearing his shirt.

Over on the women’s side of the draw, Jing fared better. She was swatting at the ball like it was a flying cockroach and intimidating her dainty Chinese opponents to great effect. She hit one girl in the eye, but most of her shots would bang in, usually less than two inches from the baseline. All the points were short, and most of them went to Jing. Using this strategy, she made it to the quarterfinals, where she got whupped by a shark.

For my early exit I blame the paddle. Jing explained to me that as I learned to play correctly, I would get used to the rubber. But I doubt her story. This is no Pro Staff. It is the Thunderstick of paddles, the prosumer model that’s priced above the company’s professional gear, sick handle and graphics, generally uncontrollable but with one spot in the middle that’s sweeter than sweet. This type of product is generally targeted at suckers like Jing and my mom: people who love the boy in their lives so much that they can’t imagine buying him anything less than the most expensive racquet on the rack.

Robin Goldstein is founder of the U.S. publishing company Fearless Critic Media and author of The Wine Trials. He currently serves on the faculty of the University of California, where he studies the economics of expert opinion and premiumization in the food, wine, beer, and cannabis industries. His next book is entitled The Bullshit Horizon.

Featured in Racquet Issue No. 6