Photograph by Geoffrey Knott

The final scene of the classic Simpsons episode “You Only Move Twice” depicts the family slinking back to Springfield after a failed move to another town. The family had only recently packed up and blown Springfield when Homer received a job offer from the Globex Corporation, run by a charming CEO named Hank Scorpio who turns out to be a real-life supervillain.

Upon their return, the family learns that Scorpio has gifted Homer a professional football team as a reward for his unwitting advancement of Scorpio’s evil agenda, and they are now ineptly practicing on his front lawn.

“Aw, the Denver Broncos!” Homer says, frowning. Marge, stunned at his ingratitude, asks what the problem is.

Homer sighs. “You just don’t understand football, Marge,” he says, slamming the door closed as an errant football doinks off a Bronco’s head.

It takes a seasoned complainer to sulk at a free ticket to see the second-greatest tennis player of the past two decades, but on a balmy September afternoon in 2009, when my girlfriend gifted me US Open tickets for my birthday, I showed my prowess, unintentionally channeling Homer Simpson. “Aw, Ve nus Williams,” I said.

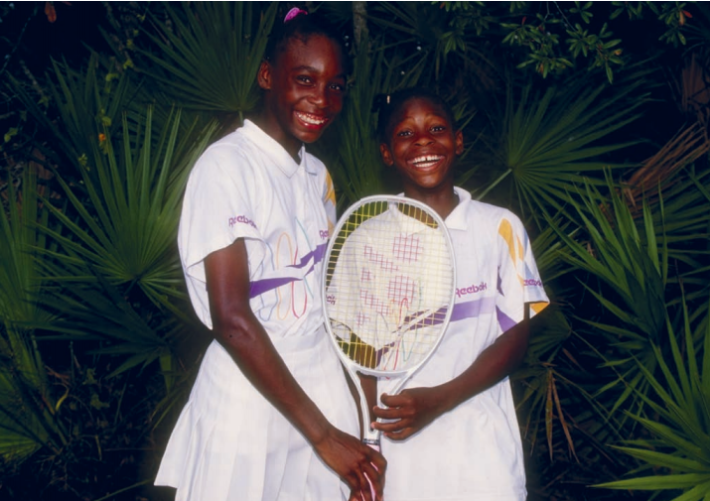

The only problem for Venus, though she’d hate that characterization—that being related to Serena is in any way negative—is that her sister is the greatest tennis player of all time. Perhaps, if the multiverse is real, there is a world or two wherein Venus and Serena combine for 46 singles titles, a symmetrical, world-record-tying 23 apiece. On our planet, the platonic ideal of tennis supremacy casts a shadow so wide that even Venus, a seven-time Grand Slam winner—and fivetime Wimbledon winner—is swallowed by its darkness. It’s not that Venus, one of the greatest players to ever pick up a racquet, cannot live up to Serena’s boisterous transcendence; it’s that no mortal being can.

Sports fans form strong opinions about sibling groups; only one can be the alpha.

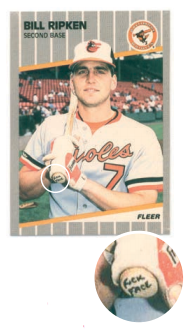

Cal is the Iron Man in the Ripken family, while Billy* will forever be associated with the phrase “Fuck Face.” If you say “Seth Curry” fast enough it can sound like “Steph Curry,” but that’s where the family resemblance begins and ends. Both Murray brothers are skilled tennis players, but when they’re standing in the same room, only one of them gets to say he ended the Brits’ 77-year men’s singles drought at Wimbledon.

When Venus turned pro as a 14-year-old in October of 1994, she had just less than a year to forge her own legacy before Serena followed. Though Serena took 1996 off from tournaments, allowing Venus to glide alone along the baseline into the zeitgeist, white braids and braces and all, even that wasn’t enough.

Patrick McEnroe, for example, followed big brother John by a full decade. John, in the interim, found time to win seven singles majors, marry famous actress Tatum O’Neal, and innovate on-court tirades with his brand-making upbraiding of umpire Edward James at Wimbledon in 1981. It didn’t help that the younger McEnroe went on to be the tennis equivalent of a Major League journeyman middle reliever, finishing his career with 140 singles wins to 163 losses. John won more than 81 percent of his 1,075 singles matches, seven of those wins coming either on the last day of Wimbledon or at the US Open. Only compounding this dominance is the elder McEnroe’s outsize—and, to be fair, divisive—personality in relation to Patrick’s dulcet tones and aw-shucks affability heard during broadcasts.

Venus almost won the 1997 US Open during her first year as a pro, losing in straight sets to Martina Hingis. By the time she won her first major, Wimbledon in 2000, over Lindsay Davenport, Serena had already avenged her sister’s loss, winning the 1999 US Open against Hingis. Not only did Serena win a major before Venus, to do so she beat an opponent who knocked her older sister out in the semifinals (not to mention the 1997 finals as well). In competition of any kind, there is nothing more debasing than coming up short, only to watch a younger version of yourself finish the job. It’s worse if you share DNA.

After the match, No. 7 seed Serena thrust the silver trophy skyward, before pointing to the spot on the cup where her name would later be engraved. A week later, Serena graced the cover of Sports Illustrated, the headline reading: “Little Sister, Big Hit.” Serena’s first, most triumphant moment in the sport was presented in the context of her big sister’s shortcomings.

June Harrison

And that trend would only continue, as Serena’s dominance on the tennis court and in the press soared. Venus won’t win even half of Serena’s record 23 (and counting) Grand Slam singles titles. Venus will not go on to date someone as famous (or famously thirsty) as Drake, or make a cameo in a Beyoncé video, or announce that she is 20 weeks pregnant on Snapchat, and thus win that year’s Australian Open (over her sister, naturally) while incubating a fetus. That makes some tennis fans—and even the unenlightened among us—pity the elder Williams, like she’s missing out.

In March 2014, International Business Times posted a list of inspiring quotes from famous Girl Scouts. One of the quotes attributed to Venus read: “My ambition is to enjoy my life and to do exactly what I want to do. And I’ll do that. I will be free.”

In considering Venus’ legacy, one may seek out intrafamily tangles, like Venus’ triumph over Serena at Wimbledon in 2008, just before the latter embarked on her ongoing and unrelenting tear through women’s tennis. The greatest testament to Venus’ singular dominance, though, is her marathon win over Lindsay Davenport at The Championships three years earlier.

At no point during the early portion of the match does Venus appear to be in control, not even near the end of the second set, when Davenport melts down to the line judge. A Venus ace had just clearly sailed wide by at least a foot. “You understand, you have to try harder than this,” Davenport complains. Venus jumps up and down nervously. Davenport is already up one set and tied 4–4 in the second when Venus gets a gift from the blind, green-blazered man sitting atop his throne. Breaking Venus there surely wins it for Davenport, but alas, Venus wins the game, and eventually the set, and the tides begin to turn. Sometimes it’s better to be lucky than to be good, but it’s best to be both.

With two break points coming during a second set tied at five games apiece, Venus slips while smashing a backhand. Davenport returns it, and Venus is forced to feebly wave her racquet at the ball, sending it a court’s length wide. “Pretty much sums up Williams’ day, doesn’t it?” the announcer says.

In the decisive third set, with Davenport up 7–6, Venus wins a 25-stroke rally that leaves Davenport bent over, dejected. She knows it’s over. When Venus finally takes her down on the first of two consecutive championship points, they embrace. Then the tightly wound spring comes uncoiled and she pogos wildly, falls on the ground, and begins to cackle uncontrollably. If you’re ever having a bad day, watch this sequence as an antidote.

The match will never be as famous as anything that happened during the comeback-laden 2016 year in sports (and, sigh, life), but it’s unquestionably the most impressive comeback in tennis history, and on a stage where the stakes are never higher.

Venus will not go on to date someone as famous (or famously thirsty) as Drake, or make a cameo in a Beyoncé video, or announce that she is 20 weeks pregnant on Snapchat, and thus win that year’s Australian Open (over her sister, naturally) while incubating a fetus.

It’s also the longest women’s final at the tournament and only one of two times that a woman has saved match point and won a Grand Slam final in the Open Era. The resolve that peeks through on Venus’ part is breathtaking, as she claws back to win her first Grand Slam singles title in nearly four years—an epoch-long drought for a Williams sister.

If her proficiency on the court at Wimbledon isn’t enough—and it should be—consider the impact Venus has made on future generations of women. Just one day before beating Davenport, Venus delivered a speech to the board at the All England Lawn Tennis and Croquet Club that denounced the pay gap between men and women at Wimbledon.

“It was one of the most stunning, poignant, powerful moments I’ve ever experienced in a business meeting,” former WTA chairman Larry Scott later said.

When that wasn’t enough, Venus wrote an op-ed the following year in the Times of London that drove the point home. “I believe that athletes—especially female athletes in the world’s leading sport for women—should serve as role models,” Venus wrote. “The message I like to convey to women and girls across the globe is that there is no glass ceiling. My fear is that Wimbledon is loudly and clearly sending the opposite message.”

When Venus beat Marion Bartoli in straight sets at Wimbledon in 2007, she walked away with $1.4 million—the same prize as her male counterpart, Roger Federer.

It’s important to mention that “You Only Move Twice” aired on November 3, 1996. To that point, the Denver Broncos were a punchline, the perfect picture of quarterback John Elway’s shortcomings. But that’s the problem with analyzing a still-forming legacy; to fully understand it requires a type of nuanced look that only a long, holistic view affords.

Over the next 36 months, Elway cemented his legacy as one of the greatest quarterbacks in history, winning two Super Bowls and making the Simpsons gag now seem silly. By the time I saw Venus annihilate Magdaléna Rybáriková in 2010, she was already one of the greats; but blinded by some combination of myopia and Serena’s radiance, I just couldn’t extricate her from her sister yet. I now see the light from Venus.

It looks like this: It’s the second Saturday of Wimbledon, and our hero has just finished stalking the tamped-down baseline on Centre Court, a tan vestige of what was, just days earlier, the picture of precision and unmarked beauty. Under the midday sun, she radiates warmth, her bright smile as white as the visor atop her head. She’s bouncing off the grass like one of her serves, screaming praise to Jehovah. She stands alone, even if her sister is on the other side of the net.

Chris O'Connell is a writer and editor in Austin, Tex.

Featured in Racquet Issue No. 4