Illustrations by Mike Reddy

“I need a racquet,” I said to my mother, hoping I had talent.

“No,” she said. This was always her frst step.

She was washing dishes, and turned of the tap.

“Yes,” I said. “I need one.”

The tap went on again. “What need one. You been playing all this time or what?”

“I’ve been borrowing people’s racquets,” I said. Then I took a deep breath, and lied. “The men at the court are sick of it.”

My mother whirled around, and soapy water splashed on my face. “What did they say?” I couldn’t convince her that they hadn’t said anything, but that they were still sick of it,

and she turned around and began to bang dishes until she broke a glass and cut herself. She seemed more hurt by what I had said than her bleeding hand, and said, “To think grown men could be so mingy with a child.” I thought of Black George and Archie, who always insisted that I use their spares, and felt guilty.

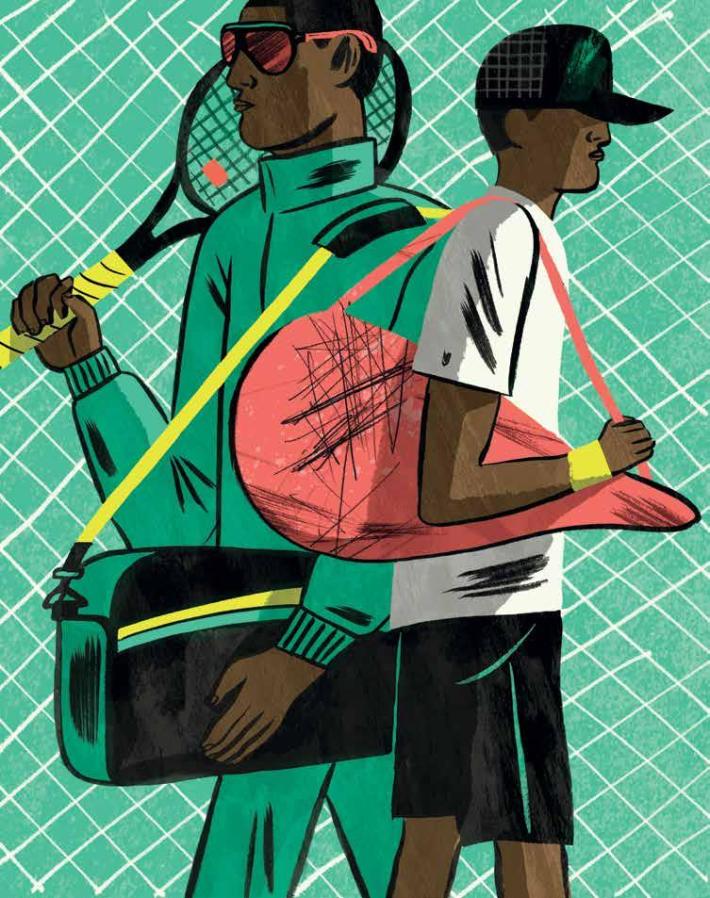

That Saturday we went to the Sports Authority in Beltway Plaza mall. My mother had been singing to herself all morning as she cleaned, but as soon as we got in the car she acted like she just remembered what she had to do. She breathed loudly and muttered to herself, and I looked out the window. I did need a racquet. Everybody else at the court had one. Delonte, Black George’s son, had a Wilson Hyper Hammer and a Wilson tennis bag so big it dragged on the ground when he slung it over his shoulder.

I had only been to Beltway Plaza once—to buy shoes, my mother informed me. Now the shoes had holes in them, and I couldn’t remember anything about the place. But the name sounded promising. It was called Beltway Plaza, and we had to take the Beltway to get there, so I assumed it was where everyone who lived of the Beltway would come to shop. I pictured a huge place with hundreds of stores somehow all interconnected in one glass building, and I was prepared for a long ride.

But as I looked out the window I saw nothing I hadn’t seen before, and I was surprised when after ten minutes my mother turned into a crowded parking lot we usually passed and said we were there. Behind the parking lot the stores were strung out in a single line. Most of them were like the stores in the strip on 450 near our house, and I inspected them all in their turn. A nail shop; a hair-braiding chain called Conywa covered with the braided heads of African princesses. A place that sold fried fsh and chicken. A pager store. 7-11. Some clothing stores and my shoe store, which I now remembered. Shopper’s Food Warehouse, and the Sports Authority.

Inside, along with the walk-in stores, were little stands that seemed to me like foating islands—a stand where you could get your own T-shirts made, a watch repair counter—all attended by friendly-looking men who called to us as we passed.

When we had to walk up the broken escalator, my mother began to mutter about P.G. County. I ran ahead of her into the Sports Authority, following the smell. It was the smell of shoes and plastic seals and things that were still brand-new, and I recognized it. It wasn’t the smell of our house. (For me, the house had no smell, but a man who came once to fx the leaking ceiling said it smelled like curry chicken.) Sports Authority, on the other hand, smelled like leather, like Black George just after he got out of his towncar. I passed the shoe section and saw people trying on pairs, and attendants standing over them. Some people had eight or ten shoeboxes around their little bench. Balls of grayish paper sat everywhere, slowly uncrumpling.

In the tennis aisle, racquets, strung and unstrung, hung of the wall on metal prongs. The unstrung racquets, with their gleaming graphite frames, were especially sleek-looking. One side of the aisle was for tennis racquets. The other side was for strings, tennis bags, and balls. Each racquet faced its matching brand of string, bag, and ball. I peered out of the aisle and saw my mother talking to a neat, hairy man in uniform. They were speaking another language. It was one of two other languages she spoke, but I can’t say I would have recognized it had he been the only one speaking. Normally I was excited and proud to hear my mother bring out this language. Two or three times a year one of her sisters would call while we were sleeping, and she would rush out and sit on the foor by the phone and talk for hours, with just enough English thrown in for me to catch the gist. Then she would do things she never did in English, like laugh until she couldn’t breathe and had to cry, or make jokes that were so wild I could hear her sister laughing. When I was asked to speak I always felt I was ruining the conversation with English; and always I was startled to recognize the voice of someone I couldn’t remember.

I came closer; my mother put her hand on my head and said to the hairy man in English, “So you get regular salary now and all?”

“Ya ya,” he smiled. “By the hour. Bonus even. Moving up in the world.”

I waited to be informed. My mother told me the man used to run one of the watchrepair islands downstairs. Everybody else in the mall had told her to buy a new watch. He had wound it up again like new.

“The rest of them,” the man went on, lowering his voice and looking around at the rest of the store, “only a pack of dufers. Customer drops shoe on the way out, they throw it and give him a new pair.”

My mother put her hand to her mouth and giggled. I looked at the thin gold watch on her wrist, which like her shoulder bag and the big brown sunglasses that took up half her face, would never get old, just as they had never been new.

I tried to pull her towards the tennis aisle, but the two of them were already walking to the back of the store, to a cramped aisle marked “Clearance.” Here everything was as it was in the rest of the store, but smaller and less expensive and arranged in no order. After some searching he found what he was looking for: a small red racquet with a short, thin handle and a gigantic oval frame. It had no visible brand or logo.

“Twenty-fve,” he said.

“Twenty,” said my mother, smiling, and he nodded as though he had been expecting this. They began to walk straight to the checkout desk.

“Wait,” I said, and dragged my mother to the tennis aisle. The small man turned and followed; as long as he was with us I felt paralyzed. I showed her the racquet I wanted, a thinframed Yonex with a special hexagonal head shape. It cost over a hundred dollars.

“When you’re older, beta,” she said, patting my shoulder. The word and the tone were new. She was looking at me in a strange way, straight into my eyes, and I felt she was begging me to go along with the new word, to behave for the small man. Suddenly I felt I might do anything. I threw her hand of my shoulder. “I need a bag,” I announced, pointing to the most expensive one, a red Prince bag that was like Archie’s. She began to murmur something, but the man was more than willing to take it down. He unzipped it, placed the little racquet carefully inside, zipped it up, and slung it over his shoulder. I thought how much better it looked on Archie’s big shoulders. He began to trot back and forth, shaking the huge bag now and then and listening attentively for the small noise inside.

He and my mother started to laugh. Before I could say anything he held up one fnger and disappeared in the direction of the clearance aisle. Again my mother gave me the begging look. I prayed the man would get called away or forget we existed, or die, but he came back; he carried with him a foppy, racquet-shaped sleeve. When he bent down to pick up the racquet I kicked it across the foor. Quickly, with her knuckle, my mother hit me on the top of my head, and as the man smiled patiently and picked up the racquet from its new place on the foor and put it in the sleeve, the spot of pain spread and spread.

“Sleeve is fve dollars,” he smiled. “Twenty-fve in total. Grand total.”

My mother nodded as though she had been expecting this; the small man cooed a little song to himself, pinning the receipt fat for her as she signed.

“I hate you,” I said in the parking lot. But I was crying and could barely breathe, and I wanted her to hear it clearly. I screamed it as loudly as I could, and felt better, then: she couldn’t pretend she hadn’t heard. She dragged me to the old shoe store to buy new shoes.

Black George said, “Boy, shut your mouth” and something about his mother spoiling him; but I ran up to Delonte, and because I couldn’t think of anything better to do, tried to hit his new racquet with mine.

He danced away, singing all the time, “L.B.! Low budget!”

For the next three days I stayed away from the courts. “I’m sick,” I said. On the fourth day my mother felt my forehead and told me to put my new shoes on and get in the car.

When I sat down I saw the foppy racquet sleeve next to me. Once we arrived, she waited until I had walked all the way up the stone steps, and then drove away.

I had feared this moment. But I had a plan. I would slink in, drop the sleeve somewhere out of sight, borrow a spare as usual, and quietly pick up the sleeve on my way out. But when I closed the metal gate it made a clang, and Black George began to walk towards me from the far court. He was wearing track pants that rustled as he walked. His jacket also rustled. “Fall warm-up suits”—I remembered a whole section devoted to them at the Sports Authority.

“New stick?” he called. Black George called racquets sticks after he heard a commentator say it on ESPN.

I shrugged, resigned, and gave it to him. I hadn’t touched it since it was bought. He unzipped the sleeve. The handle was still short and thin, the head still enormous. In Black George’s hand it looked even more like a toy.

But he didn’t laugh. “You can’t play with this,” he said.

“I know,” I sighed. But I was curious what he thought. “Why not?”

“It’s better racquets than this at the Commissary in Dover,” he said. The Commissary was a grocery store. Black George could shop there for free because he was in the Air Force Reserves. Still frowning, he turned the racquet over once or twice more, and then looked up. “Wait for Archie,” he said. “I need to check something with him. In the meantime you going have to use one of mine, if that’s okay with you?” We both smiled, and he said, “You see my bag?”

When Archie drove up in his big carpet-cleaning truck, I didn’t want to give up Black George’s racquet. It let you hit as hard as you wanted without even trying. The handle was cushioned with a spongy black overgrip, which Black George replaced dutifully every few weeks. At the base of the head, fastened to the strings, was a round dampener that cushioned your arm from too much vibration when you hit the ball. It was like playing with a very powerful pillow. I replaced it in his bag, next to his towels, bottled waters, and two or three other identical racquets. Archie’s frst love was basketball. We didn’t know what injury had put an end to his career

and made him become a carpet cleaner, only that when Maryland played its great rival, Duke, he had to turn of the television. “Y’all could sit back and watch it for fun,” he said. “Not me.” So it made sense that his passion for tennis fell on coaching rather than playing, and that he knew so much about equipment. Now, he and Black George discussed my racquet with concern. Eventually he told me to pick it up and put my hand around the handle. My hand wrapped around the grip and my thumb wrapped around my fngers.

“See! I told you!” said Black George.

“Too small,” Archie said, rubbing his chin. “Grip’s too small.”

With slow efort he bent over his stomach and removed one of his racquets from his bag. He put his hand around the handle, also covered with a plush black overgrip. There was space between his thumb and fngers.

“You see that?” Then he plugged the gap with the forefinger of his other hand. “See how tight that is?” he said. “If you do that and your fnger don’t fit, grip’s too small. If it’s still some space left over, too big.”

Black George said, “Where you learn that again?” Archie, having replaced the racquet in his bag, set up a folding chair by the net and seated himself.

If my finger doesn’t fit it means it’s too small,” I said to my mother.

Throughout my explanation and demonstration I had been surprised to see her nodding with concern. She seemed especially impressed by the finger test. When I finished, she still hadn’t spoken. I waited.

“And where you learning all this?” she asked.

“Archie.”

“How does he know?”

“He knows.”

“Mmm,” she said, and gave me a smiling look. “You told him ‘Look-at-thischeap-racquetmy-cheap-mother-bought’?” She tried to dig her fngers into my stomach to tickle me, but I moved away, shaking my head furiously.

There was a silence. I couldn’t wait any longer.

“So I can get a new one?”

“We’ll see,” she said. I showed no emotion. She looked up at me wonderingly, and took my right hand and examined it, frst the front and then the palm.

“Such big hands. Too big for a child.” I tried to pull my hand away, but she pulled it back. “When you grow up, who will take care of me?” She nudged me, and made a show of look

ing all around her. “Cat? Dog? The boy who hates his mother? No, you’ll go away and leave me behind in this place, I know it. To get old.” Now she was laughing and pretending to see things in my palm.

“I think I will die right here. Like this.” She threw her heavy black hair into her face and let her tongue fall out of the side of her mouth and lay down on the carpet; and for some reason I could not stand to look at her lying there, where the crumbs fell from the foam table we always ate from. But she went on talking from her new position.

“When I die they’ll fnd me and put me on the table. Wrap me in the cloth. I’ll ask them to throw my ashes in the crick outside the house. Where will they end up?”

“Creek,” I said without thinking.

“Creek. In the creek.”

But when I fnally wrenched my hand free, her mood had passed. She stared at the ceiling, and she didn’t sit up for a long time.

The next afternoon I came home from school and decided the time was right to bring up the Sports Authority. And then I saw it, propped against the side of the dining table. She must have done it in the morning, after I left for school, before she drove to work. The racquet handle was covered in black tape, the same sort of glossy tape she used to seal the basement windows when it got cold for the winter. I felt the handle. It was not plush. It had no cushioning. But the wrapping was perfectly smooth; there were none of the little ridges that always formed when I tried to put down a piece of tape. You could only tell there were two layers from the very top, where a tiny piece of the lower layer peeked out. I didn’t dare perform the fnger test, and left the racquet where I had found it.

After an hour or so my mother came home, made me a snack, and said, “Not bad, eh?” “It looks stupid,” I said.

“No,” she said. “It looks nice. Check check, test test!”

My fnger ft snugly; the grip was the right size.

Beaming, hardly able to contain herself, she said, “Am I a champ or what?”

“It’s so ugly.”

“No,” she said again, and I could hear her voice hardening, “it looks fne. Enough now.” Again she drove me to the courts; again she waited until I was at the gate to leave. “Go

show Archie!” I heard, and she drove away.

But Archie wasn’t there. There were only Black George and Delonte, doing his monthly hour of visitation. Black George always told his ex-wife to drop the boy at the courts rather than his house, and Delonte always showed up with something new his mother had bought him. This month it was a new vibration dampener for his Hyper Hammer, a little W that matched his shoes, racquet, and bag.

“What is that?” he said, as soon as he saw I was trying to hide something.

Black George said, “Oh, you got yourself a new overgrip.”

“Ain’t no overgrip!” Instantly Delonte was on my side of the net, and moving closer. As soon as he saw that it was tape, he began to howl, “L.B.! L.B.!”

Black George said, “Boy, shut your mouth” and something about his mother spoiling him; but I ran up to Delonte, and because I couldn’t think of anything better to do, tried to hit his new racquet with mine. He danced away, singing all the time, “L.B.! Low budget!”

We began to hit, Black George and Delonte against me. It was the frst time I had hit with the racquet, and I was playing well. Everything was going in. Black George was working on his new slice backhand.

“It’s going be ready soon,” he kept saying, but half of his backhands sank to the bottom of the net. The other half barely skimmed over, and one was so low I scraped my frame on the court trying to get it.

I jerked it up immediately, thinking that might undo it, but at the top of the frame, above the strings, was a white gash where there had just been deep maroon paint. To look at it was to know the racquet would never be new again.

“Tape it up!” I heard Delonte call. Black George shook his head.

On the next low ball my racquet scraped again, and I felt powerless to stop what had started. Delonte laughed; I scraped once more, to make a joke of it and show I didn’t care. And suddenly I didn’t. We began to laugh together, and soon I was scraping my racquet to get balls that weren’t low at all. The maroon paint was almost gone now: it was on the court.

“Keep doing that and you ain’t going have nothing left to play with,” said Black George, but I ignored him. I fung the racquet in the air like the pros finging racquets into the crowd to celebrate big wins, and I didn’t bother to position myself underneath it.

I could hear Delonte cackling, almost unable to breathe, as the racquet fipped over itself, faster and faster nearing the ground. It fell, headfrst, making an unsatisfying little noise a few feet from me.

Black George shouted and began to make his way to my side of the net.

But I reached the racquet before he reached me. The top right side had caved in; the strings at that corner no longer formed neat right angles, but were slack and crooked. Quickly, before Black George could do anything, I picked up the racquet and began to bash the top left side against the court. The sound was better now, a crunching; and now Delonte didn’t laugh. When I looked up at him and smiled he looked back with big eyes and an open mouth.

I was being shaken. I let Black George take the racquet from me. Before I knew it he was taking me to his car, and then we were parked behind my mother’s car. As he knocked and the front door opened, I looked at the driveway, flled up for the frst time with two cars, and thought it made the house seem like another place.

My mother was not hysterical. She barely finched when she saw Black George. She gave a little gasp when she saw the racquet. Then, holding open the screen door, she began to look him up and down as he spoke. I can’t remember all that he said. He seemed to lose his courage once the door was opened and talked as though it were all a big accident. After a while, without interrupting him, she took the racquet—he was holding it—and examined it. Only the very top of the frame was as it was—a funny little mountain surrounded by huge dips to the right and left. The handle seemed to belong to a diferent racquet. It was the handle my mother looked at longest, and just once did she lower her eyes to me. It took us both a moment to realize that Black George had fnished, that he had been trying to say the same thing for some time.

“He could use one of mine. I got plenty”—he stopped himself—“I got a couple extras. I don’t mind, and he used to it too. It could be just for a little while, you know, before he, you feel like getting him another one. Or I mean he could just have it too; I got this deal and I basically be getting them for free anyway so—”

My mother, realizing abruptly what was being ofered, took her eyes of the racquet and said, “That is very generous of you but we don’t need any charity in this place.” And she took me inside and shut the door.

At school I heard of classmates whose mothers grounded them and sent them to bed without dinner. I wished my mother would do that. But every Sunday she stayed up past midnight cooking dinners for the week. It would only be her food and work that was wasted, so that night I had to face her while we ate in silence. Afterwards I came back down and saw her still sitting in her chair, food drying on her fngers.

It was like that for a few days. She only spoke to me to wake me up and announce food, and I didn’t speak to her at all.

And then on the weekend she told me to put on my shoes and get in the car. And again I saw the racquet sleeve next to me.

I felt that enough time had passed for me to risk a question, and asked where we were going. She didn’t answer.

The smell in the store did nothing for me: our frst sight was the hairy clerk. He was wearing pants this time instead of shorts. They were belted and pulled high above his waist. When he saw us coming he put his hands in his pockets and rocked back and forth on his heels.

“Broken string already?” he said. “He hitting too hard for his own good.”

“No,” my mother smiled, “no.” It was a shock to see her manner change. She became delicate and sheepish and very correct. “I’m afraid there was a bit of a problem with the racquet. It seems”—and here she took a deep breath, smiled with embarrassment, and stopped speaking English.

The man spoke back, quickly and softly, nodding all the while. Eventually the sleeve was unzipped, and he looked frst at me and then at my mother. She wanted him to take a closer look, but he refused to touch the racquet and took a step away.

“Ma,” I whined quietly, realizing for the frst time what she was trying to do. She ignored me, and from their faces I could tell they were no longer agreeing. He spoke better than she did; and while she grew more agitated, raising her voice and using more English, he spoke back mellifuously in words I could not understand. Eventually my mother was protesting entirely in English.

I tried to pull her away, but she pulled so hard in return that I stumbled back.

“People are looking,” I whined.

“Let them go to hell,” she said; and then people did start to look.

The clerk quickly took them in, before settling back on us and saying in English so loud and perfect that it might have been tape-recorded, “This is no wear and tear. This racquet has been destroyed. There is no warranty. If you like you may lodge a complaint with my manager but I will tell you now it is a waste of time.”

My mother seemed shocked by the ofcial tone, and by the time she looked up, ready to begin again in soft, smiling whispers, the hairy clerk was helping other customers. I wanted to do nothing in the world as much as leave, but she began to wander aimlessly through the store, and I followed her. We came to the tennis aisle.

I stood still, while she passed up and down the aisle without seeming to look at anything. Suddenly she stopped, and looked back at me. “Well,” she said, giving me a tired smile, as though I had calculated everything to arrive at this moment. “This one?” She pointed to the $100 Yonex.

I shook my head.

“What happened? You don’t want it now?”

“No,” I said.

But she insisted, and in the end I agreed to one that was twenty dollars cheaper. My mother was still carrying the foppy sleeve, so we didn’t need a bag.

Kannan Mahadevan is a graduate of the University of Iowa Writers’ Workshop, and has written for the Los Angeles Review of Books and the Los Angeles Times. He is at work on a novel. Wear and Tear is one of 12 stories from A Public Court, a linked collection set on four neighborhood tennis courts in a suburb of Washington, D.C.

Featured in Racquet Issue No. 3