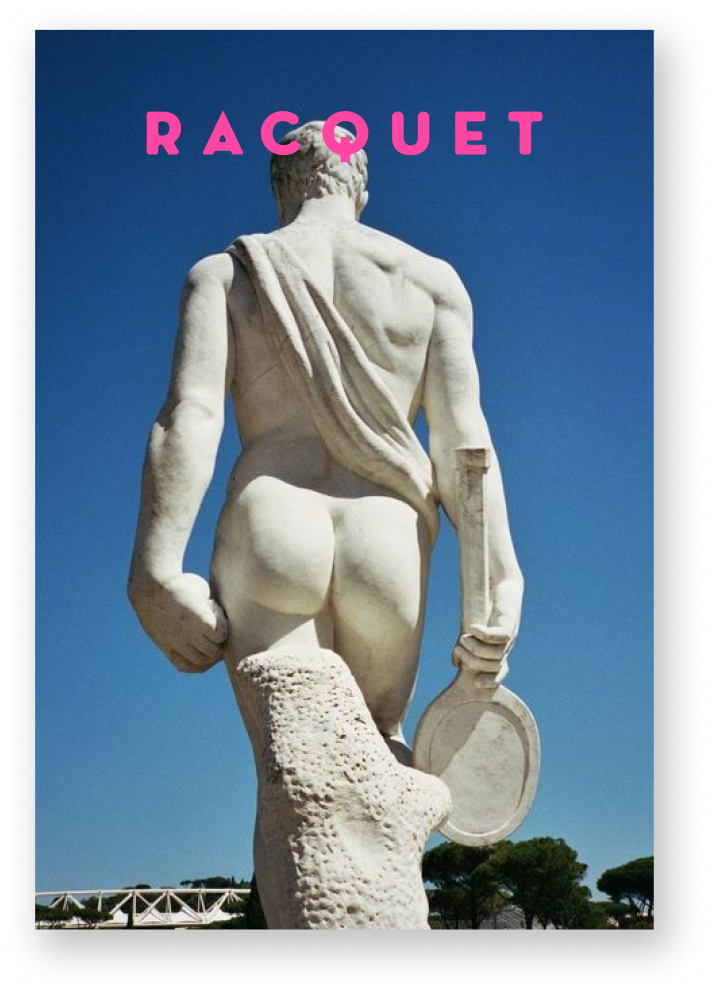

Digital Cover

Roma

For May's digital cover, a look at how tennis changed one photographer's relationship with his hometown

Featured Articles

Portofino or Bust

Sease, with a little help from Feliciano Lopez, takes over the Italian Riviera.

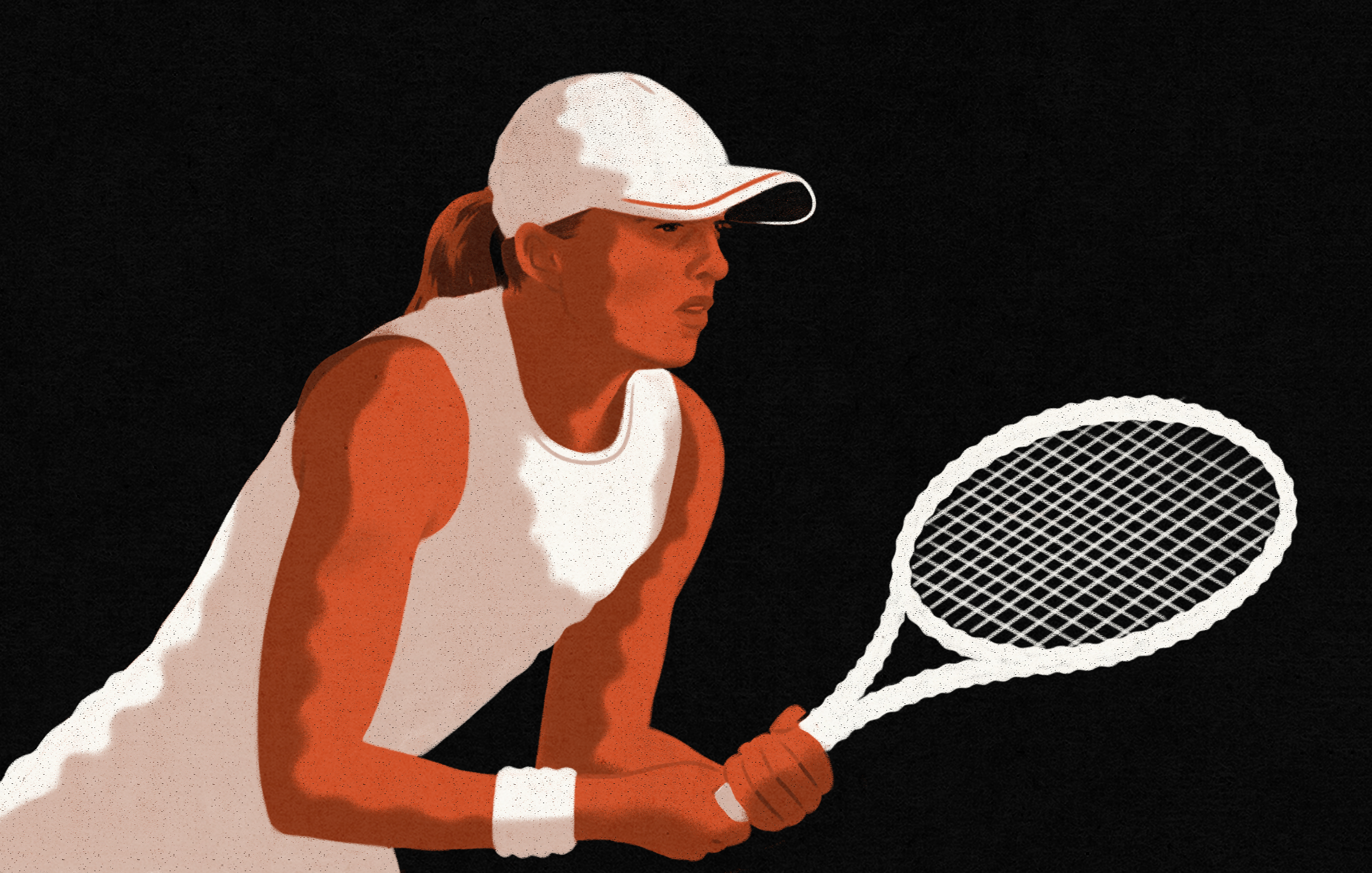

The Worry Index

What do Iga Swiatek, Novak Djokovic and Coco Gauff have in common (besides some Grad Slam titles)? They're all officially on our Worry Index for players who need to turn things around to reset their season. We talk about the chaos agent that is Jelena Ostapenko, the rebound of Holger Rune and some scattered pot shots from deodorant to shower drug tests.

Watching What I Can’t Have (A Hit)

Something to know about me in 2025 is that I’ve become the neighborhood voyeur. Four freshly renovated tennis courts opposite my apartment beckon me daily; a hooked index finger tempting me with good, honest time. An hour’s all I need to thrash about, try and prove something inconsequential to myself, defog the mirrors of my mind and leave a better woman. Only instead of playing, I watch.

The Magazine

From the Magazine

Tennis Is Not the Literary Sport

In his Essay on David Foster Wallace, John Jeremiah Sullivan flirts with a distortion of category

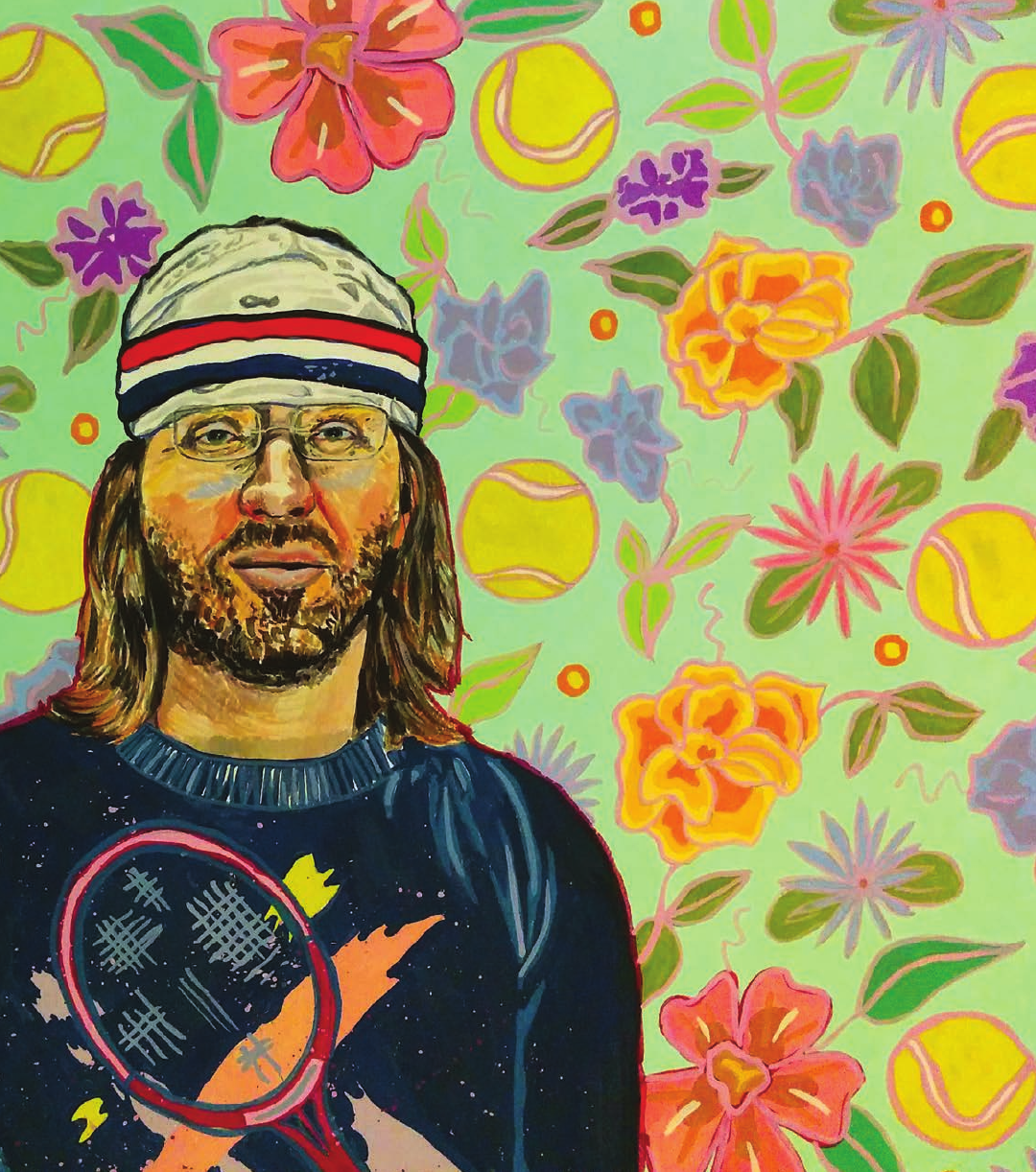

Tennis Lessons

Taffy Brodesser-Akner had resisted tennis her whole life and had finally found a way into it, found a way to be her own scrappy self among its inherent elitism

Seniors Rule!

The ladies playing at the highest levels of the “vintage” circuit are not to be trifled with.

Shop

Issue No. 26

In our first-ever travel issue, we drop in on courts and tennis culture from all around the world.