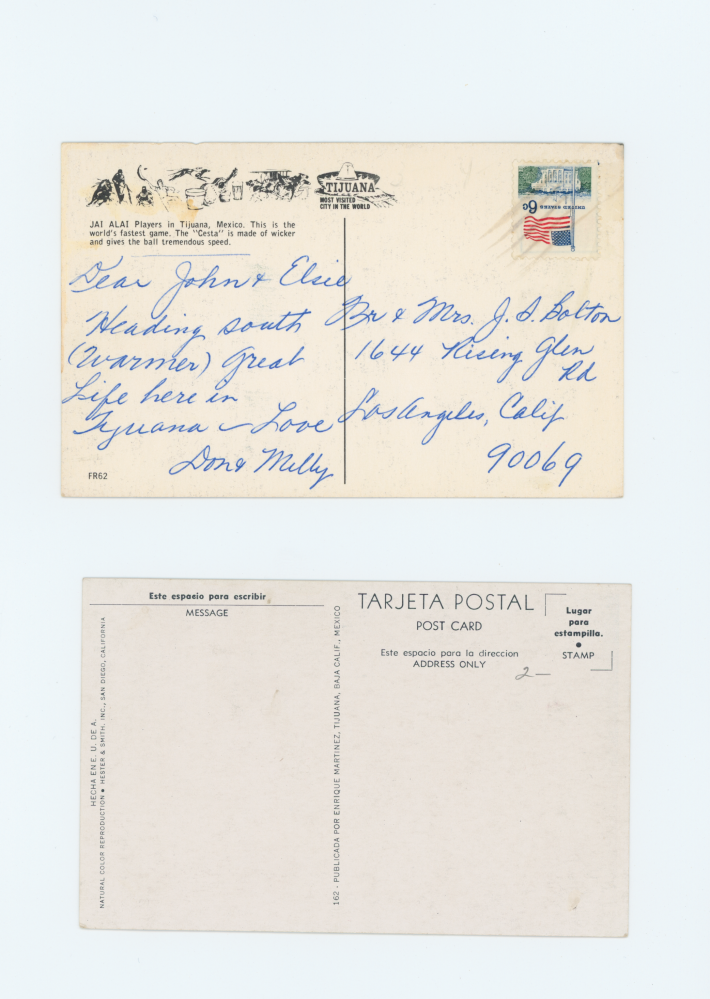

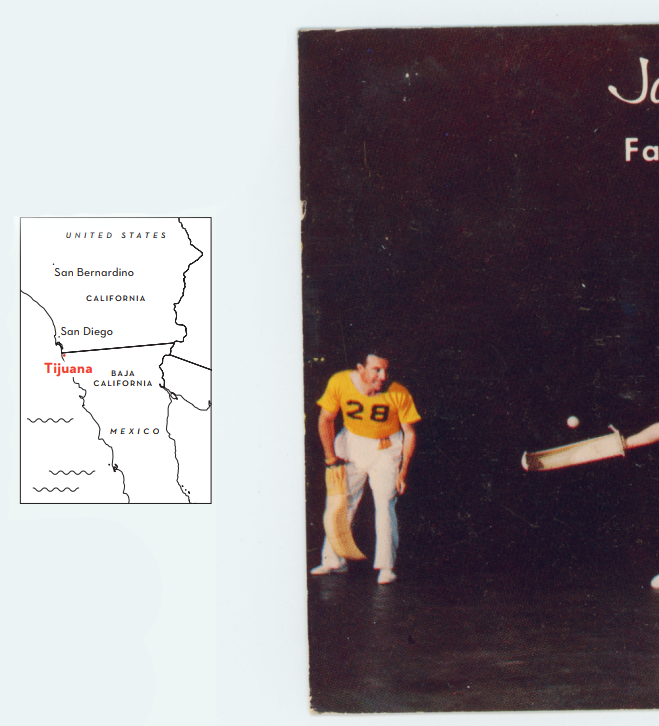

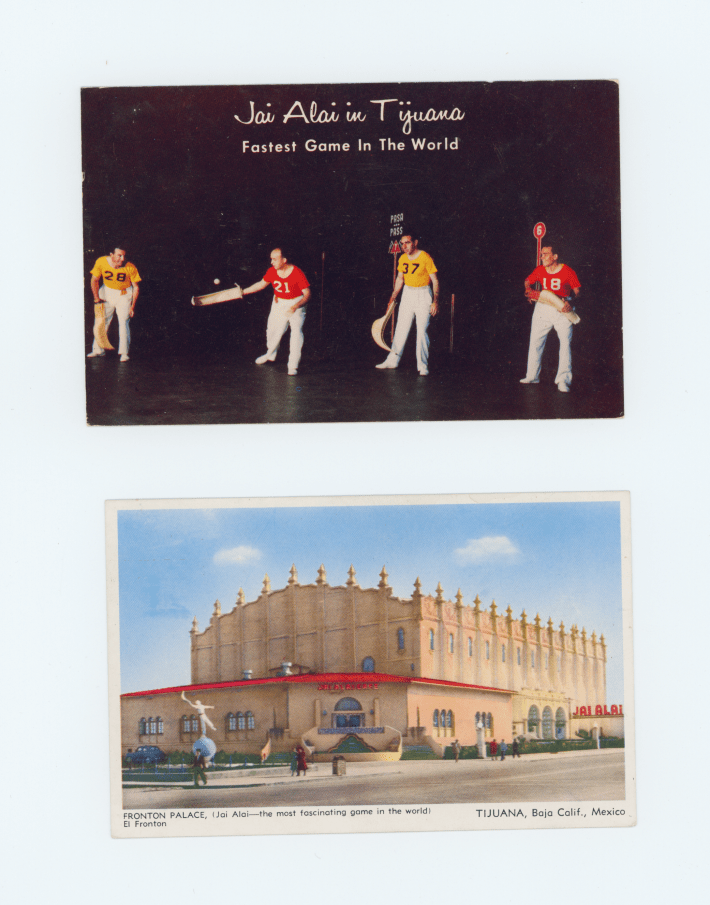

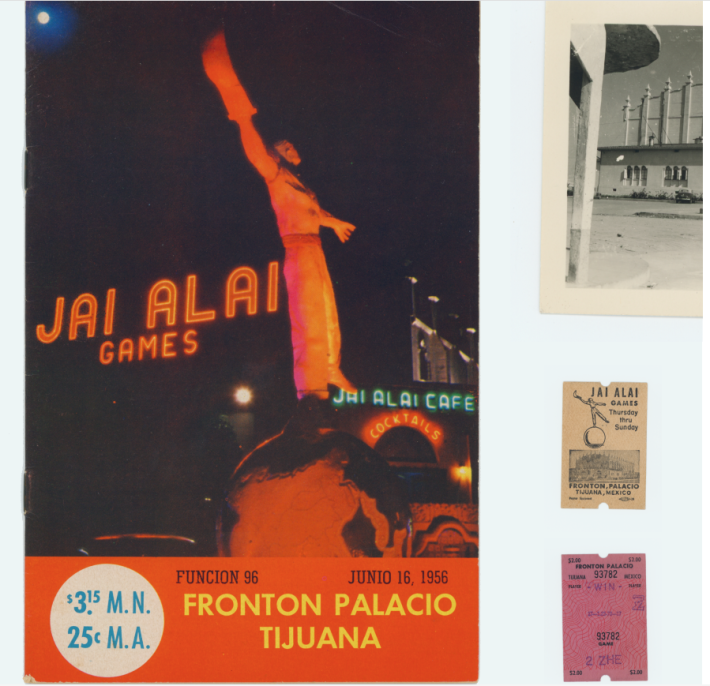

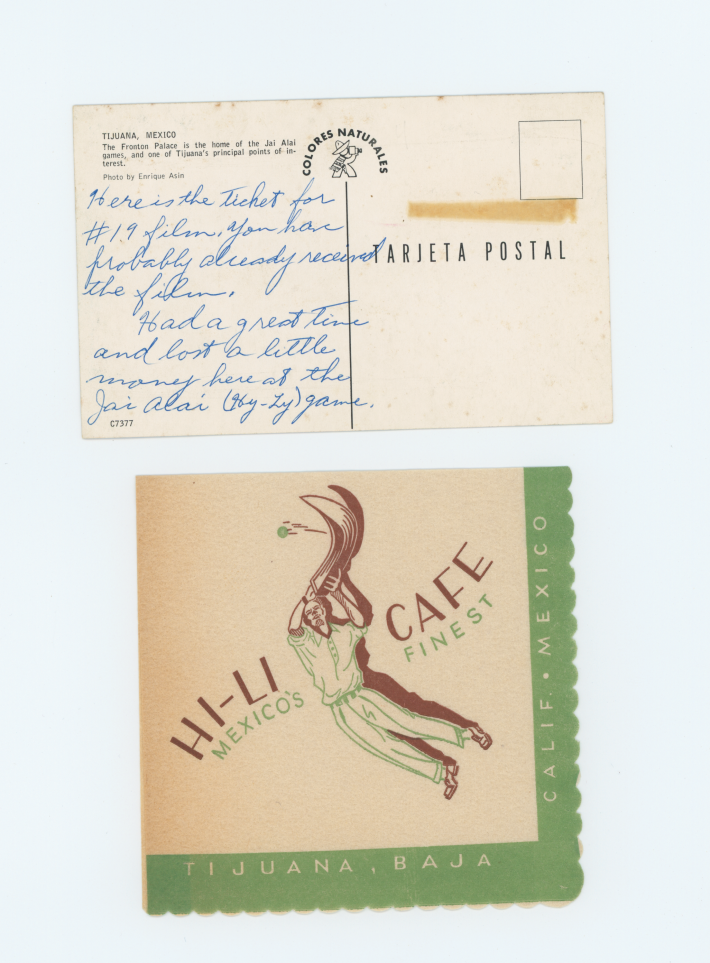

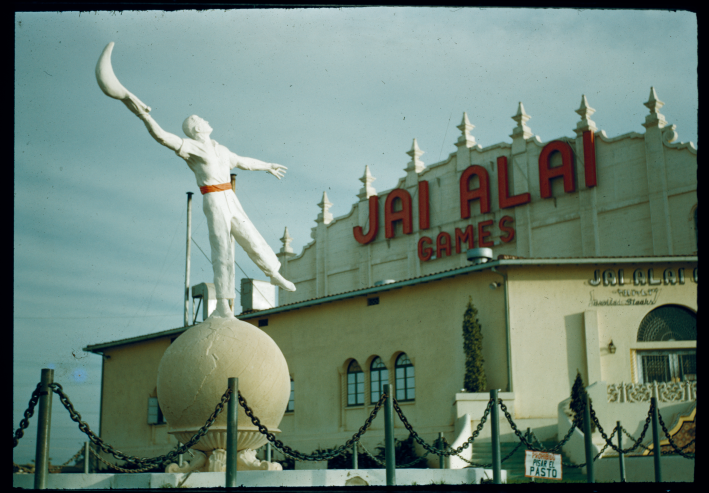

The back of a faded 1960s postcard addressed to “John and Elsie” in Los An geles reads “heading south (warmer), great life here in Tijuana.” Nowadays it’s hard to imagine Mexico’s preeminent border town being referred to in such glowing terms. For decades it’s been fodder for drunken-gringo tales of debaucherous adventures. More recently, narco-violence and now bigger walls and immigration battles dominate Tijuana’s narrative. Flip that old postcard over and you’ll be transported to a time and place where things were more glamorous across the border. There’s a photo of a majestic arabesque edifice with an inviting bright-red sign that says “Jai Alai.” The header on the postcard reads “Fronton Palace, Jai Alai— the most fascinating game in the world.” More recently, 62-year-old Beques Ramos Elorduy was enjoying a rainy Saturday after noon off of Tijuana’s main Revolución drag from a corner seat at Chiki Jai, a historic local Basque restaurant that dates back to the 1940s. He was having some laughs with a friend over beers, shots of tequila, and plates of Spanish tapas.

Behind Elorduy, through the restaurant window, was that same bright red “Jai Alai” sign from the postcard. It still lit up at night, calling people to the build ing below, once known as Fronton Palacio, or just “El” Palacio (the Palace). Now called El Foro (the Forum), the last jai alai match played here was 20 years ago.

But then the building was converted into a music ven ue as a way to make more of a profit. It no longer offers a chance to see one of the world’s most rare—and for those who know and play it, beloved—sports.

“I get sad when I see the sign,” said Elorduy, a star player at Fronton Palacio in the ’70s and ’80s when jai alai was still a thing. Sad is a strange emotion to feel to ward jai alai, considering the words literally mean “merry festival” in the Basque language. This distinctive court game, with hints of—and perhaps some of the same roots as—tennis, racquetball, and squash, was exported from northern Spain to colonies in the Americas and the Philippines more than a century ago. It debuted in the U.S. at the 1904 World’s Fair in St. Louis and caught on as an official sport in Miami in the 1920s. The game features players slinging hard rubber balls stitched with goatskin covers, “pelo tas,” from handwoven reed baskets, “cestas,” against an enormous wall made of granite, one of the few materials strong enough to weather the game’s inherent barrage.

Alberto Lau

The improbably long 177-foot courts, called frontons, are lined with a front-, back-, and left-side wall. The right side is a view ing area with a protective cover for fans to cheer and jeer the players. Frontons were featured in exotic locales like Miami, Macau, Las Vegas, Havana, and Acapulco. And some less sexy-sounding spots, too, like Milford, Connecticut. For audiences the draw was often betting. A modernized version of the game was developed as a kind of third op tion for the horse-racing, dog-track crowd. It features round-robin tournaments called quinielas, where teams of two, one backcourt player and one frontcourt player, square off. Up to eight different teams compete at a time and rotate in and out as points are won and lost. Like tennis, there’s an initial serve, and jai alai players score when they force the ball to touch the court twice before their opponents can sling it back against the wall. The first team to reach seven points wins.

Beques Ramos Elorduy is Mexican, but his mother’s side of the family is from the Basque part of Spain, where the roots of jai alai and its best players go all the way back to the 13th century.

The original game was called pelota, a sport that is closer in style to handball and still exists in Spain. Players hit small rubber balls covered in wool and leather against a three-walled court with their bare hands. In the early 1800s, baskets—or cestas—were added to the mix, and jai alai was born. Many of the best jai alai players still come from academies in the Basque part of Spain, and some from France, too, where there are still professional seasons.

One of Elorduy’s relatives was a world-champion jai alai player. Elorduy him self represented Mexico at a World Cup of jai alai. “You play ’cause jai alai is in your blood,” he said wistfully, polishing off another shot of tequila. “That passion is essential. You don’t do it to get rich.” The most money he ever made playing was around $2,000 a month.

A Chiki Jai waiter stopped by Elorduy’s table with a black-and-white photo. A mus tachioed Ernest Hemingway is sitting, grin ning on a stoop, surrounded by a crew of jai alai players. Included in the mix is Pedro Garate, a Basque champion who played at Fronton Palacio and ran this very restaurant for a stretch. This corner of downtown Ti juana was once a living epicenter of jai alai greatness. Now the only hint of jai alai action on Avenida Revolución is a statue in front of the stadium of a player stretching his cesta to the sky.

While the epilogue seems to have been written for Tijuana’s one true jai alai fron ton, the sport itself is not dead yet in Mexi co’s Baja California. On a Sunday afternoon on the eastern outskirts of Tijuana, near the city’s airport, local sports park Unidad Deportiva was bustling. The luring smell of charcoal and carne asada lingered over a youth softball game as taco vendors fed par ents near home plate. An enormous swim ming pool and tennis courts forged from copious amounts of concrete were crum bling a bit as they led to a gleaming soccer field, clearly the space that gets the bulk of the funds here. Hidden in the far corner of the complex was an enormous wall and long green court striped with yellow lines. A group of men in their 50s and 60s strapped long baskets to their wrists and began to shuffle around the surface. Their joints were creaky, but as they collected and flung a ten nis-size plastic ball on the fly, this endeavor was clearly more ballet than beer-league.

“Most people that come by here, they have no idea what this is,” said Loren Harris, stopping to narrate what’s going on to a gaz ing couple with tennis racquets. He’s had to explain jai alai more than a few times since he first fell in love with the sport as a Flor ida teen. After stints in Spain and his native Miami, Harris wound up signing a contract to play in Tijuana. He’s a bit of an odd duck in a sport that’s almost exclusively featured Spaniards and Latinos. Jai alai gave him his life. He met his wife while playing in Baja, and he settled in San Diego, close enough to keep playing a few more years.

The 176-foot-long court and 40-foot-high wall are still intact but are disrupted by a stage, dropped like a boulder on top of a surface many consider sacred.

Back in the ’80s, playing jai alai in Tijua na was exotic and cool, said Harris. It meant meeting Hollywood stars—he got to teach Bo Derek how to play—and doing jai alai ex hibitions before San Diego Padres baseball games.“I played in the last game they had before they closed it,” Harris said. He lost that game, and then he lost access to Fron ton Palacio.

Harris and a group of other local veterans in their 50s and 60s recently formed Asoci ación De Pelotaris de Baja California in an attempt to revive their sport. The group includes Tijuana native and former jai alai champion Manuel Quezada, who played in Miami and was known as “el Cartucho,” which roughly translates to “gun cartridge,” referring to the velocity of his throws. The old staff doctor from the stadium, Alberto Álvarez Melero, is also a member. He admit ted the sport has left a lot of these veterans with chronic injuries. “Jai alai shoulder, jai alai elbow,” he said, laughing.

The crew gets together on Saturdays to play for fun. On this day they threw a fund-raiser for the local cesta repairman Vi cente Lopez. He was in the hospital, and the group was making a paella and putting on a formal exhibition to go toward his medical bills. Lopez worked at Fronton Palacio, and is one of the last local artisans who knows how to repair the intricate woven center pieces to the sport. Many of the cestas be ing used at this gathering were reinforced by tape to keep the materials together.

Even the jai alai version of the soccer mom was there. Forty-two-year-old Verónica Osuna wore a Sunday dress and white sun hat as she helped set up water and snacks at a table. She runs an after-school program out of a Catholic church compound in Tijuana’s “Zona Norte, ” one of the city’s roughest neighborhoods. “We provide a place for kids away from the violence,” she said. Many of the kids in her program live with grandpar ents because their parents have disappeared because of drugs, violence, or crossing the border. “It’s an environment totally contam inated with assassinations, prostitution, the drug trade, and mental illness,” Osuna said.

A year ago, kids from Osuna’s after-school program stopped by a concrete court on the church’s grounds. Some of the jai alai veterans were there practicing. “When the kids first saw them they weren’t into it, because they wanted to use the space,” Osuna said. “Even tually some of the kids got curious, and the old-timers said they’d teach them how to play.”

Thirteen months later, a few of these kids were already winning youth tournaments around Mexico. One of the young champi ons, Leonardo Soto, glided around the yel low lines of the green court with youthful ease. He scooped up the ball with his cesta, which was almost half his size, and in one flu id motion sent it back into play high off the monstrous wall. Pausing to let a few friends get in some reps, Soto stood to the side, ea ger to rejoin the fray. “I’m good with the ces ta, and I can cover the court quickly,” he said.

Soto’s 12, and he acknowledged that for a Mexican middle schooler on the border, baseball and soccer are still the draw, but he’s working on that. “My friend Fabricio was playing soccer, and I was like, ‘I’m going to play jai alai.’ He tried my cesta on—now he plays jai alai.” Osuna said soon a group of young girls from Zona Norte were going to start training too.

What they’re inheriting does not look the part of the once-glamorous Tijuana jai alai scene. It’s a little more Bad News Bears, with an old van for a changing room, a couple of worn municipal courts that are half the length of professional ones, and a hodgepodge of equipment: frayed cestas, hockey helmets (cheaper than finding proper jai alai ones), and a mixture of synthetic and plastic balls instead of the traditional leather-coated ones.

Organizer Loren Harris said they’d wel come more young players to join their train ings, but they simply don’t have the ma terials. “As we get stronger, we need more equipment, we need more cestas. They’re expensive,” Harris said. Some of the kids use plastic versions of cestas, others have hand me-downs from frontons in Florida.

The veterans and newbies recently took a trip down to Mexico City to see jai alai matches at a professional fronton recently reopened after 20 years. The kids even got to meet one of the current world champi ons, a Basque named Imanol López. Know ing there are professional games nearby is a boost for Soto and his cohort. “My dream is to play in Mexico City and other countries— Spain, France,” he said.

Thirty years ago Soto would have been dreaming of staying at home to play jai alai. His new mentors were lucky enough to grow up playing at Fronton Palacio, which hosted a youth academy. To get a closer look at the building is to understand why these veterans are so bitter they can’t access their old sta dium. It’s a literal cathedral, with flourishes straight from the famous Alhambra fortress in southern Spain. The design is Morisco, re flecting a period of architecture in Spain when Arabs were forced to convert to Christianity.

The brick building is cream-colored with a series of elaborate minarets across the roof. The front steps are highlighted with blue tile trim and lead up to three large entry ways with tall white arches, decorated with red, yellow, and green painted lattice designs. Enormous wood doors lead into a sweeping lobby with polished concrete floors.

A row of arabesque windows line the far wall; that’s where jai alai fans used to place their bets be fore games. Another lobby wall features an endless chalkboard where scores from the evening matches were recorded. All the signs are in both Spanish and English, a nod to the audience across the border that helped keep this facility going for 50 years.

Mariano Escobedo Jr. inherited Fronton Palacio from his dad, who constructed it in of arabesque windows line the far wall; that’s where jai alai fans used to place their bets be fore games. Another lobby wall features an endless chalkboard where scores from the evening matches were recorded. All the signs are in both Spanish and English, a nod to the audience across the border that helped keep this facility going for 50 years.

Mariano Escobedo Jr. inherited Fronton Palacio from his dad, who constructed it in Ibón Arrieta, is “the most beautiful fronton in the world.”

A 20-year jai alai career took Arrieta from his native Spain to Cancún, Newport, Rhode Island, and Tijuana, where he retired and opened a Basque restaurant called Pam plona. On a nostalgia tour of Fronton Pala cio, something he does when relatives and friends visit from Spain, Arrieta stopped and admired what was once his Centre Court at Wimbledon. It was being desecrated by the long-haired roadie of a band warming up for an evening concert. “Check one, check two,” the man belted in a heavy English accent.

The 176-foot-long court and 40-foot-high wall are still intact but are disrupted by a stage, dropped like a boulder on top of a sur face Arrieto calls “noble” and many other jai alai greats consider sacred. “We lost a spec tacular sport, a beautiful fronton, a long tra dition of years and years of jai alai,” said Arri eto. “Sadly, it’s just the times—we can’t point a finger at anyone in particular,” he added.

Palacio owner Mariano Escobedo Jr., now in his 70s, has stayed in touch with some of his former star players like Ibón Arrieto. He accompanied Arrieto on his tour of Fron ton Palacio and stopped at a wall of photos in the building’s lobby. There is a picture of a blond-beehived Ms. San Diego from the 1950s presenting a jai alai player with a tro phy as the mayor of Tijuana looks on, cra dling a jai alai cesta. Escobedo said the most successful season for the palace was 1970–71, when it came close to making money com parable to some of the Florida frontons. But that didn’t last, and as sports became a TV thing in the ’70s and ’80s, jai alai began to really suffer. “It was ranked behind bowling,” said Escobedo, accentuating just how hard it was to grow an audience for a sport few peo ple had a history with.

The heydays of jai alai in North America were the early to mid-’70s when Escobedo, he said, was able to make some decent money. During the ’80s and into the ’90s, the num bers stopped adding up in Tijuana. The ad vent of satellite betting meant people could watch from remote betting locations. Fewer fans paid to actually come to Fronton Palacio and pay entrance fees. The general upkeep of jai alai was pricey, too. Escobedo said his large staff included artisans to repair the cestas and sew the specialized balls. “Soccer you can play in the street, in whatever place. Jai alai you need more things,” he said. Lastly, he said labor unions made things complicated. In the U.S., a players’ strike in the late 1980s is credited with expediting the sport’s demise. Finally, in the late ’90s, Escobedo acknowl edged that the real estate Fronton Palacio sat on was worth more than keeping the heart of the building—the fronton—going.

Back on the other side of town, Leon ardo Soto and his friends couldn’t be both ered with talk of the beautiful fronton they were missing out on; they were happy to play wherever. It had been only a year since he first tried on a cesta, but Soto already had the weight of a few dozen former Tijuana pros on his shoulders, and the legacy of an endan gered sport. As he waited his turn to jump back onto the court, Soto studied his friends play. He may not have fully understood what he’d gotten himself into yet, but the passion was there. “Bonito, no?” he said as he head ed for the fronton. It had been two decades since the last professional jai alai match in Tijuana, long enough for the sport to disap pear from local people’s consciousness. But as a group of scrappy kids from the wrong side of Tijuana’s tracks absorbed the nuanc es of the game from its gatekeepers, a new “merry festival” seemed possible in northern Mexico.

Jesse Hardman is based in Los Angeles, reports regularly for NPR, and runs the national community journalism project listeningpostcolletive.org

Featured in Racquet Issue No. 5