Photos by Torben Eskerod

Tennis loves a comeback story— the former champion turning back the clock amid the lengthening shadows of her career, say, or a fan favorite defying medical odds for one last tilt at the title. But few stars have bounced back quite like Leif Rovsing, one of Denmark’s first professional tennis players. A strong serve and an iron will took him to the summit of the game at the start of the 20th century, but when the sporting establishment cast him out for being gay, Rovsing reconstructed his tennis life in his own worldly image, in the process building of one of the world’s most extraordinary tennis clubs.

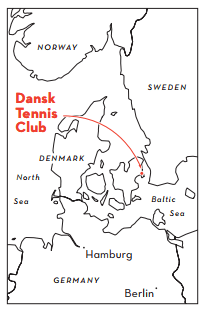

Rovsing would surely be forgotten today were it not for Dansk Tennis Club, which he established in Copenhagen’s wealthy northern suburbs in 1919—two years after he was expelled from the sport he loved. His remarkable story is recounted in Out!, Danish architecture professor René Kural’s illuminating profile of Dansk Tennis Club and the scandal that led to its foundation.

Nestled in a residential neighborhood in Hellerup, the little-known architectural wonder is made almost entirely of wood—aluminum window frames arrived in 1987—and has a striking cantilevered roof. It is big enough to contain just one elegant tennis court.

The indoor court, Copenhagen’s second-oldest, is a splendidly serene spot, a tramlined temple of tennis where the air is always cool and light—the court remains unheated even in winter—and the atmosphere calm.

Notably, the court lacks overhead illumination. According to Kural, Rovsing disliked the early tennis halls, which had windows directly above the court that made serving and receiving lobs tricky. Instead, his court is illuminated by sidelights that “shed a soft parallel light over the courts without blinding the players.” Large canvas screens, as pretty as sails, shield the court from direct sunlight.

The court’s color palette is stunning. The playing surface—once made of felt, now modern latex—is moss green and steel blue. Elevated platforms at each end—designed for spectators—are painted dark ochre.

Mustard yellow, oxblood red, and pine green dominate other hard surfaces.

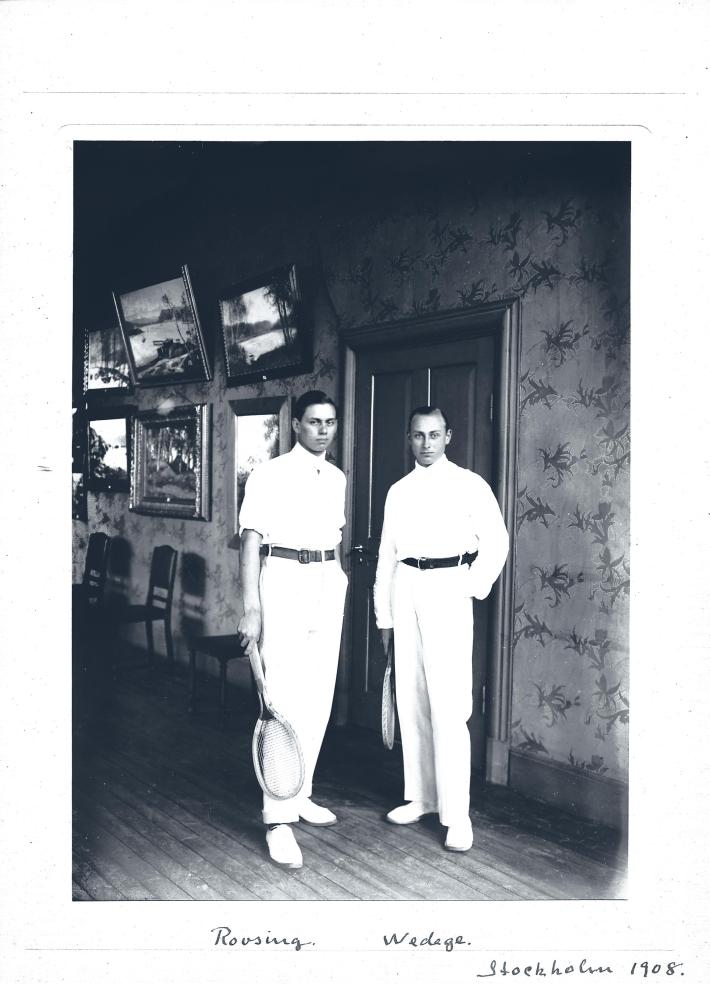

Kural claims that Rovsing’s inspiration for “light intake, materials, color choices, ornamentation and layout” came from the indoor courts he had played on in Stockholm. At Dansk Tennis Club he sought to replicate the refined air and intimacy of those early Swedish pavilions.

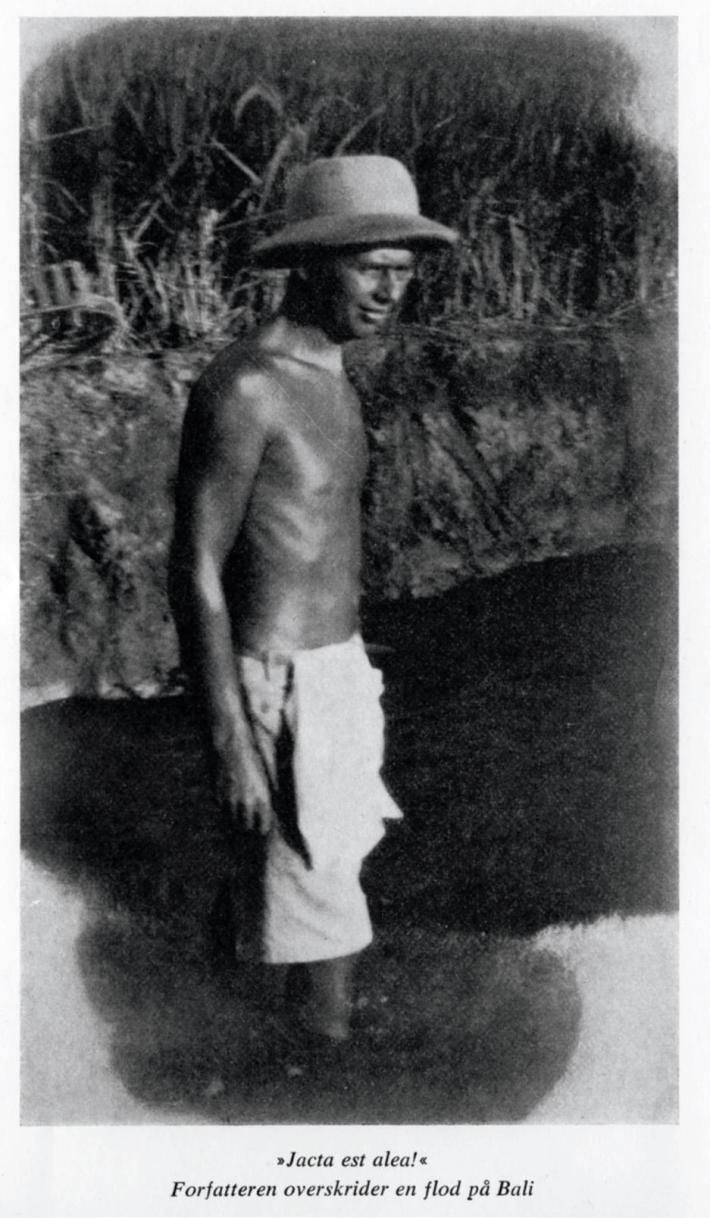

Rovsing traveled far and wide and was fond of both Egypt and Bali. Like many people at the time, he was fascinated by Egypt, where Tutankhamen’s tomb had just been uncovered. And in Bali, Rovsing found an exotic and licentious environment where he could finally enjoy a measure of sexual freedom denied him in Denmark. Both cultures influenced the tennis club he founded.

Accordingly, the club has a uniquely flamboyant character that is apparent the moment you step inside it. Colorful Egyptian paintings feature throughout the building and cover the western flank of the court itself. A depiction in the same style of the “judgment of the dead” dominates the lobby, while the clubroom—where members once lounged on plush sofas, enjoyed tea and cakes, and browsed books and magazines about tennis—is adorned with both Egyptian and Balinese paintings.

According to Kural, this exoticism reflects not only Rovsing’s eccentricity but also his “perception of the tennis sport in Copenhagen as small-minded and provincial”—and his desire to turn his gaze away from Denmark and the conservative mores that sunk his successful career.

Born in Copenhagen in 1887, Rovsing was a talented athlete who competed at Wimbledon in 1910, represented Denmark at the Olympics in Stockholm in 1912, and won several titles. He could be brattish, too—once storming out of a tournament in Stockholm after disputing a foot fault called against him.

Yet in the fall of 1916, an 18-year-old engineering student claimed Rovsing had tried to seduce him. Rovsing denied the accusation and said the student—the son of a bank president—had sought him out instead, but didn’t deny having homosexual relationships, Kural writes.

Unimpressed, the Danish Ballgame Association pronounced him “to be not only a homosexual but also even more of a threat to the younger generation because of his views on sexuality,” according to Kural. Though homosexuality was not a punishable offense under Danish law, the DBU expelled Rovsing in May 1917 and banned him from competing in Danish tournaments. A court later upheld the verdict, ending Rovsing’s career.

By then, though, Rovsing had established Dansk Tennis Club—or what he termed a “World Sports Establishment.” Having founded the club in 1919, Rovsing officially opened it on Oct. 8, 1922, playing an exhibition match on the new court. Two years later the clubhouse, with its well-stocked library and Balinese decorations, was completed.

Rovsing sank plenty of his own money into the project. He had inherited a fortune from his father and later estimated that he had spent some 350,000 Danish kronor— about $1.6M today—building the club. He died in 1977, having set up a foundation that helps to ensure the club’s existence. In the years that followed its launch, Kural says, it developed a “somewhat decadent reputation, perhaps due to the many well-known members and the rumors of Rovsing’s homosexuality.”

Membership remains highly coveted and is often passed down from one generation to the next. Indeed, much of the club’s charm derives from its unique booking system. The club is open between Sept. 1 and April 30, and from 7 a.m. to 10 p.m., seven days a week. Members pay 2,600 DKK (about $380) for a regular weekly slot.

When I visited the club one Saturday morning in April I found Marianne Jensen, a 46-year-old hairstylist, trading ground strokes with her 12-year-old daughter, Ella. Toweling down later, Jensen praised Rovsing for being a “first mover” in a sport that remains “old-fashioned and conservative.”

The club, she said, is a “very special” place, not only because of its “lovely lighting” and intimate atmosphere but also because “there’s a lot of freedom here and you can have fun.” No doubt that’s a legacy that would have made Leif Rovsing deeply proud.

James Clasper is an English journalist based in Copenhagen. He has worked for the Associated Press, Financial Times, The Guardian, and The New York Times, among others.

Featured in Racquet Issue No. 5