Photographs by Luke Sharrett

I’m in a basement in Nicholasville, Kentucky, staring at shelves of old tennis ball cans.

The cans are packed tightly together, stacked nine high on custom-built shelves against a gray cement block wall. Lit only by a single bulb tucked between the beams of the low ceiling, the cans dazzlingly reflect and refract the limited light. While the older metal containers glimmer brightest, the shiny wrappers on the newer plastic cans do their best to iridesce. Less bright but still resplendent, there are shelves to one side full of the old cardboard boxes that held the earliest tennis balls.

As a whole, the wall of vibrant colors on the shelves gleam in a spectacular spectrum, illuminating the dim chamber as if by stained glass, bringing to mind the unlikely image of an old-world cathedral.

The colors vary randomly, but order is maintained. While the containers have evolved, ball size has not fluctuated much over the past 150 years (the International Tennis Federation mandates tennis balls must be between 2.57 and 2.70 inches wide), so the cans have remained a pleasingly uniform width. They bear a constellation of tennis stars past and present: From Fred Perry and Don Budge through to Roger Federer, players’ images have been slapped on cans in the hopes that fans will scoop them up. Other non-sporting icons, such as Mickey Mouse and Hello Kitty, also appear.

Aside from aesthetic appreciation, the cans can also tell history. As packaging technology improved, the containers changed. Before the modern plastic cans, and the metal cans that preceded those, the oldest ball containers were cardboard boxes, which didn’t hold the pressure of the balls well. War is also represented: Cans made during World War II bear stickers indicating that they were made from substitute materials and contain no crude rubber, which was under strict rationing as the rubber fields in Southeast Asia were under Axis occupation. To save metal, there were also wider cans that held 12 balls, shaped more like coffee cans.

Culture can also be interpreted in the collection. Nearly all modern cans are a uniform height as well, for holding three balls, except for ones from Japan, which hold only two.

“You’re expected to bring a can every time yourself,” my host said of Japanese tennis culture. “Three-ball cans from both people would be too much, but if I bring two balls and you bring two balls, we are good.”

“That’s how it was explained it to me, anyhow,” he added. “I don’t know if that’s true, but it makes sense.”

I am in the home of Dr. Michael Eden, a family-practice physician in Lexington.

He lives in the suburbs in a spacious house off of an uncomfortably narrow road lined with horse fences.

I met him in Australia, where he was a guest of a group of collectors there at the Royal South Yarra Lawn Tennis Club. He was on a diplomatic visit of sorts, representing the Tennis Collectors of America, an organization that he cofounded.

He showed off photo after photo after photo of his collection, impressing and perhaps exhausting the affable Aussies with the depth and breadth of his wares.

His own story as a collector begins during the tennis boom of the 1970s and early ’80s, which reached deep into America, including Elizabethtown, Ky., where he grew up. Places to play there were scarce, however, so tennis courts were strictly rationed as the sport’s raw materials had been decades before.

“There were 10 public courts there in Elizabethtown and they had a one-hour time limit,” Dr. Eden recalled. “Behind every court there was a timed meter, like a parking meter. After one hour, people were lined up getting your court. It was crazy back then.”

Dr. Eden played regularly in high school, but also found a place away from the crowded courts to scratch his growing tennis itch: garage sales.

He’d previously kept more standard collections of stamps and coins, but tennis paraphernalia soon became his objective.

“It was this old Slazenger metal can that was made in South Africa,” he said of his first find. “This is about the time they were transitioning over to plastic cans, and I thought, ‘Yeah, that’s kind of cool.’ Then I noticed some old racquets that I thought would be kind of cool to have someday. It went from there, and it became pathological.”

Now he has not only old racquets, but some of the rarest in the world. One particularly impressive septet of racquets fan out in pleasing symmetry, their handles meeting in the middle to allow for easy comparison of their varied bases. One has a fishtail, another a ball tail, another a fantail.

“This is the rarest racquet in my collection,” he said, holding one with a baseballbat-style handle. “And look at it: It’s perfect.”

“In the beginning I didn’t realize there were

all these other people who were

like me. Weird like

me.”

He’d used the word “pathological” somewhat in jest, but I had indeed come to Kentucky prepared to render a diagnosis of some sort of madness. I had held out hope—for the sake of you, the reader—that I’d find something irresistibly irregular, delightfully deranged. How, after all, could a “normal” person devote so much time and effort to accruing all this tennis detritus? He’d paid to have an old pinball machine shipped from North Carolina just because it had tennis-themed decals. What would motivate a person to do that?

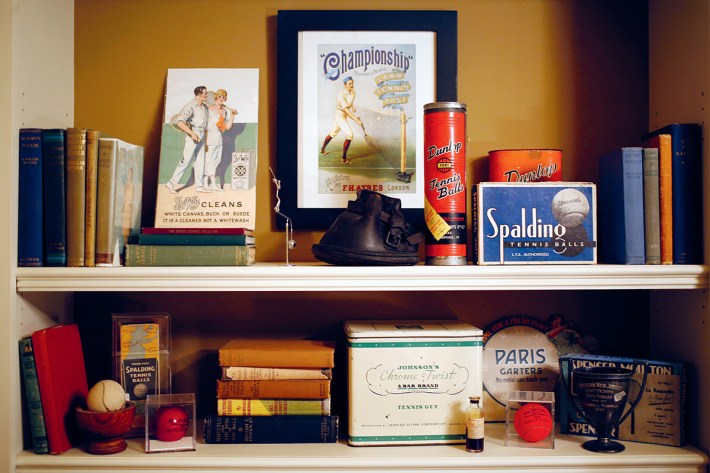

Dr. Eden described his collection as “a little bit of everything, with pretty extensive collections in lots of different areas.” The bulk of his collection is stored in the basement, but a smaller showcase in his groundfloor office houses some of his favorites. He owns all 23 books written by Bill Tilden; most valued is a signed first-edition copy of Match Play and the Spin of the Ball, considered Tilden’s best work. He also owns every issue of Tennis magazine, save for five issues from its inaugural year of 1965.

“Maybe someday I’ll find them,” he said wistfully.

Lots of people own books and stacks of magazines. Fewer own an old tin that was used to hold gut for stringing racquets. Fewer still, probably, own a single leather horseshoe, designed with rubber padding so that the horse didn’t damage a grass court as it pulled a roller used to smooth the surface.

“Being in horse country, I knew about these,” he said. “I had to get one.”

Tilden’s best work. He also owns every issue of Tennis magazine, save for five issues from its inaugural year of 1965.

“Maybe someday I’ll find them,” he said wistfully.

Lots of people own books and stacks of magazines. Fewer own an old tin that was used to hold gut for stringing racquets. Fewer still, probably, own a single leather horseshoe, designed with rubber padding so that the horse didn’t damage a grass court as it pulled a roller used to smooth the surface.

“Being in horse country, I knew about these,” he said. “I had to get one.” not to say it too immediately.

One of the things that attracts my attention is a small green container with a crank that looks like a miniature bank-vault door. He tells me it was designed to seal a tennis ball inside to keep its pressure for longer.

“I don’t think it did anything,” he said. “I don’t think it worked, but it’s kind of neat, and most people have never seen that.”

“And have you ever seen one of these?” he said, handing me an oversize egg cup with bristles all around its bowl. I correctly surmise that it would have been some sort of ball cleaner.

“I don’t think it did much, either,” he said, shrugging. “But it’s cool.”

His most practical collection is perhaps his least spectacular: assorted baseball caps from tennis clubs and tournaments.

“Because I’m bald and need hats.”

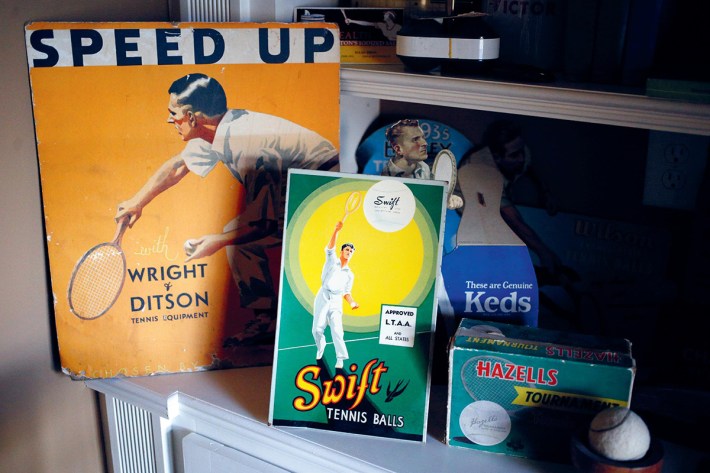

His favorite things to enshrine are the things most designed to be temporary: standup displays used to market tennis equipment in pro shops, usually cardboard. He recently got a Wilson display kit from 1966 that was never even unpacked from its original box. Another prized display came from an out-ofbusiness sporting-goods store in Michigan, sitting unused in a back room for three or four decades. He’s also bought ads for other items that had tennis themes, including ones that were used on streetcars.

“There’s always a story behind everything you found,” he said. “This stuff to me, they’re all works of art. They really are.”

Eden has worked to cultivate a community of those who agree. He’s served five 1-year terms as president of the Tennis Collectors of America, which broke off from the British-based Tennis Collectors Society in 2003 and is incorporated in Lexington.

There are currently just over 100 members, though more than 400 people have been on their rolls at some point.

“We’re kindred spirits, there’s no doubt about that,” he said of his tribe. “We have this instant connection. And it’s deep, because very few people in the world have this love of tennis artifacts.”

Areas of interest and approaches vary among collectors. Some are generalists, and some have specialties. Denis Tucker, whom Dr. Eden stayed with in Tasmania during his trip to Australia, is working on a collection of autographs by any person who ever won a Grand Slam, many of whom have been dead for over a century. One collector in the San Francisco area has over 3,000 racquets in his house.

“He can’t just have one, he has to have multiples of a certain era. It takes up his entire house. He lives in his collection.”

Eden’s collection is contained almost entirely in several rooms of his large basement—a visitor to the ground floor of his home might have no idea what multitudes were stored beneath.

While Eden has traveled far and wide to meet other collectors, so have they made special trips to his Kentucky home to peruse his treasures.

“There aren’t that many people who appreciate what you’ve got, so when you have somebody come to your house to see your collection, it’s a big thing,” he said. “It’s really exciting to share it with them. In the beginning I didn’t realize there were all these other people who were like me. Weird like me.”

The tour of his collection always ends in the basement, facing the wall of cans. “I don’t know—these things just appeal to me,” he said as we stared at them. “I just love all the variations, the colors. All the people who come here who aren’t really into the collection but like tennis, this is the room I always have them come to last. Because they’re like, ‘Wow.’”

I was, indeed, like, “Wow.”

I wish I could tell you that Dr. Michael Eden is as odd as his collection. It would have been more satisfying to find a twitchy, skittish kook, pale from not seeing the sun since he spends his life indoors staring at his collection. Maybe I could have found a forgotten family pet buried under a pile of old racquets. But I didn’t. What I found was an exceptionally polite and gracious man, well aware enough to know that he has done something few would.

“I’ve thought about it myself: What’s driven me to want to do this?” he said, contemplating the edifice of cans before him. “Well, I’m OCD like most collectors, and I’m also OCD as a physician, which is not a bad trait to have because I have to think about all these possibilities and I don’t want to miss anything. And I’ve always enjoyed organizing things and finding them and putting them together.

“And I love tennis. I’ve found that tennis people, they don’t understand the level of doing this, but they think it’s really cool, because they love tennis. They love seeing all this stuff—even though they would never take the time or effort to do it themselves.”

Luke Sharrett is a freelance photographer based in Louisville, Kentucky. He is considered one of the most accomplished, profound, prolific, and handsome photographers in the history of photojournalism, according to his mom.

Featured in Racquet Issue No. 5